Today we have another contribution from Timeless Travels Magazine in which Archaeologist Ben Churcher explores the highlights of a visit to Petra a ‘rose red city, half as old as time.’

As an archaeologist who has been privileged to travel widely, I’m often asked “what is your favourite site?” While the pyramids at Giza are awe-inspiring in their size, the ruins of Palmyra in Syria evocative in their desert location and the Lion Gate at Mycenae majestic, I always answer “Petra” as no other site in the world is quite like Petra.

As an icon for Jordanian history, this popular and much-visited site is simply stunning. No other site in the world can match the entry into Petra and nor can they compete with the sheer artistry and labour that was expended in the creation of the site’s monuments. The oft quoted description of Petra as ‘the rose-red city half as old as time’ is almost right: the site is set in a chain of rose-red (and yellow and buff) mountains, although the site, for an archaeologist, is not ‘half as old as time’.However, I won’t let dry academic niceties detract from the more romantic notions that do capture the feeling one gets when at Petra.

No other site in the world can match the entry into Petra and nor can they compete with the sheer artistry and labour that was expended in the creation of the sites monuments.

Although a settlement has existed at Petra at least from the Iron Age (ca. seventh century BCE), what visitors see today dates from an amazing floruit that occurred at the city around and shortly after the time of Christ. The builders of Petra were the Nabataeans, an Arab people who grew rich by controlling the overland route bringing vital incense from Saudi Arabia to the markets of the Roman Empire. To understand the importance of incense in the ancient world one must remember that, in what we would regard as an unwashed world without the modern levels of hygiene, the aroma of frankincense and myrrh would have been near essential to mask the smells of the every day.

In addition, mountains of the exotic fragrances were burnt during religious ceremonies and it is no coincidence that the three wise men of Biblical fame presented the young Christ with gold, frankincense and myrrh: three equally valuable commodities of the time.

Frankincense and myrrh are both sourced from the sap of low, thorny trees that are endemic to southern Saudi Arabia and Yemen and Petra, located in southern Jordan, was ideally situated to control the trade routes bringing the incense north to Roman market places. Nor were the Nabataeans confined to Petra alone; at their zenith before Roman territorial conquests in the first century BCE, the Nabataean Kingdom stretched from southern Syria to the Hejaz Coast in Saudi Arabia and their influence spread even further.

Petra’s history

It is no wonder that this trading entrepôt attracted the attention of the Romans as their interests turned to the Near East during the late Republic. The first clashes came in the middle of the first century BCE but it was not until 106 CE that the Nabataean Kingdom was formerly annexed into the Roman Empire, becoming the province of Arabia Petraea. The trading skills of the Nabataeans ensured that Petra continued to not only survive during this period but positively flourish and it is from this time that most of the monuments we see today date. Still occupied during the Byzantine period (fourth century CE and following), the strategic importance of Petra had begun to wane. The main reason for this was the ‘discovery’ of the monsoon weather pattern by the west during the Hellenistic Period (fourth to first century BCE) when traders sailed directly to India from the Red Sea, bypassing trading centres such as Petra. Like most things, this discovery took time to be widely used, but following 50 BCE more and more trade was utilising the prevailing winds and slowly the overland trade routes dwindled. Later, in the Byzantine period, Christian ceremony still used incense although not in the quantities used in the pagan temples. This double-blow of declining demand and being marooned from the main trade routes meant that the power and influence of Petra gradually faded although it was never abandoned. While memory of Petra vanished from western consciousness, the ruins and caves that dot the Petra area were used by the local Bedouin, the Bedul, as their home. Indeed, this situation continued until the modern period when the Jordanian government moved the Bedul families from Petra itself to a new, nearby settlement at Umm Sayhoun. However, for better or worse, the Bedul remain ubiquitous at Petra both as a reminder of their past occupation of the ruins and, increasingly, as touts and sellers involved in the tourist trade.

You have plenty of time to ponder this rich history as you make your way into Petra. On leaving Wadi Musa (The ‘Valley of Moses’ where a spring is shown to you where Moses struck a rock with his staff to get the waters flowing) and purchasing your entrance ticket, you have a two kilometre walk to reach the ruins themselves. In the past people could hire horses with which to make this trip but the crush of horses and the dust they raised prompted the Jordanian government to insist that the journey be done on foot, although for those really unable to walk the distance there are horse-drawn carriages available. But the walk is well worth it!

This article was originally published in Timeless Travels magazine. Republished with permission.

At first the valley is broad and beside the road are the first rock-cut tombs you encounter. These tombs, utilising the natural rock, are carved into blocks symbolising the personification of the

Nabataean god Dushara who was represented as featureless pillars or blocks. These tombs involved cutting away the whole top of a

hill or cliff face so as to leave only a block behind into which a

small chamber was chiselled. Sometimes adorned with merlons (stepped or crenelated parapets), or sometimes left plain with perhaps just a carved pediment above the door, the function of these structures, as well as the more elaborate ones within Petra itself, were part tomb and part used by families for feasting in the company of their ancestors. The larger are examples of façades par excellence. The viewer is presented with a soaring, elaborately decorated edifice, yet inside is a plain room often only with rock-cut benches on which the family would have reclined during their feast days. Also to bear in mind when looking at these structures is that while we are wowed by the striated and colourful sandstone that we see today, when in use these rooms were plastered and covered in frescoes. Often the roof had scenes from agriculture or the garden and the walls were decorated with frescoes to resemble block-work to make someone on the inside think the structure is built of stone blocks rather than being carved from the mountain itself. Additionally, we must imagine walled enclosures, often with gardens, in front of the façades, all of which have now vanished. So while the structures show their rose-red sandstone face today, when new they would have been softened by gardens in front and the sandstone covered inside and out with coloured plaster work. A very different scene to what we see today.

Entering through the Siq

After passing through the broader valley you turn a corner and cross a modern dyke which prevents flood waters from entering the narrow entrance to Petra, the 1.2 km long Siq. The modern dyke replicates an ancient one (look to your right and you’ll see the tunnel the Nabataeans carved out to carry away the flood waters) and is a necessity after a 1963 tragedy in which 23 French tourists and their guide were swept to their deaths by flood waters before the ancient dyke had been re-built. At the entrance to the Siq, an arch, until recently, marked the formal entrance to Petra. Although the arch has now collapsed, you can still make out the arch supports and imagine how the scene once looked.

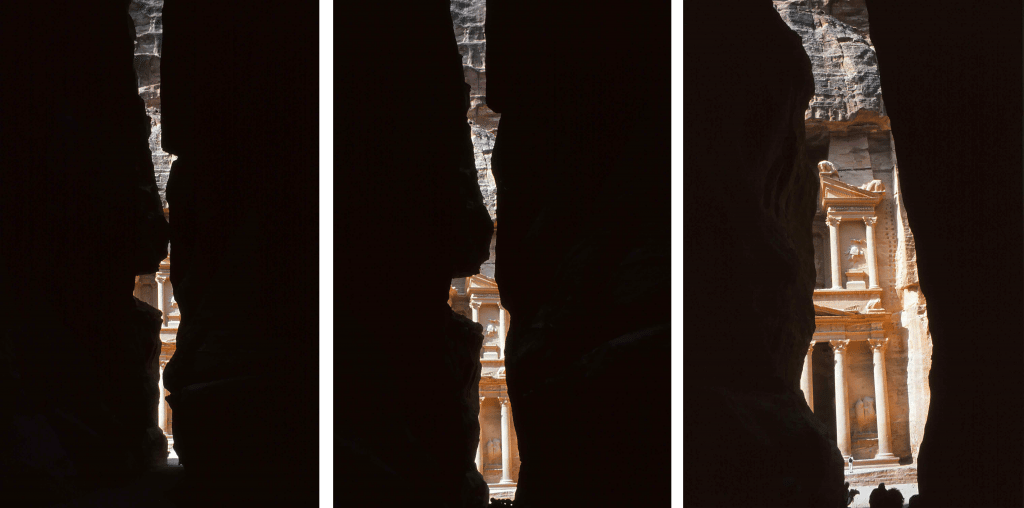

Then you enter the Siq proper. Shaped by nature, the Nabataeans made the Siq their own, paving the road, carving small temples, niches into the walls, and water channels along the side. Like something from an Escher drawing, stairs seem to lead up into nowhere. Although weathered by wind, rain and time, what remains hints at the grandeur that met visitors to the site 2000 years ago.

As cliffs soar perpendicularly above you for 150 m, scenes reminiscent of medieval Japanese landscape painting greet you with every turn. The spectacular rock formations, clinging, stunted trees, and, way above, the blue desert sky make for wonderful imagery. As you walk along the Siq you can only imagine the mounting excitement that must have been felt by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt who was the first outsider to visit the ruins when he made his journey of re-discovery in 1812.

Burckhardt had mastered Arabic by the time of his visit and, in disguise using the name Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah, he convinced the suspicious Bedul that he was a pious man who wanted to offer sacrifice at the tomb of Haroun (Aaron) which is located on a peak overlooking Petra. Burckhardt tells us that he was watched like a hawk and could not take too much interest in the ruins he was seeing in case it confirmed the Bedul’s suspicions that he was a treasure hunter, but inwardly he must have been jumping out of his skin to be the first westerner to set eyes on Petra in over a millennium. Burckhardt never made it to Jebel (mountain) Haroun as he ran out of time and offered sacrifice in the lower city before retreating and telling the outside world of his discovery.

El Khasneh and beyond

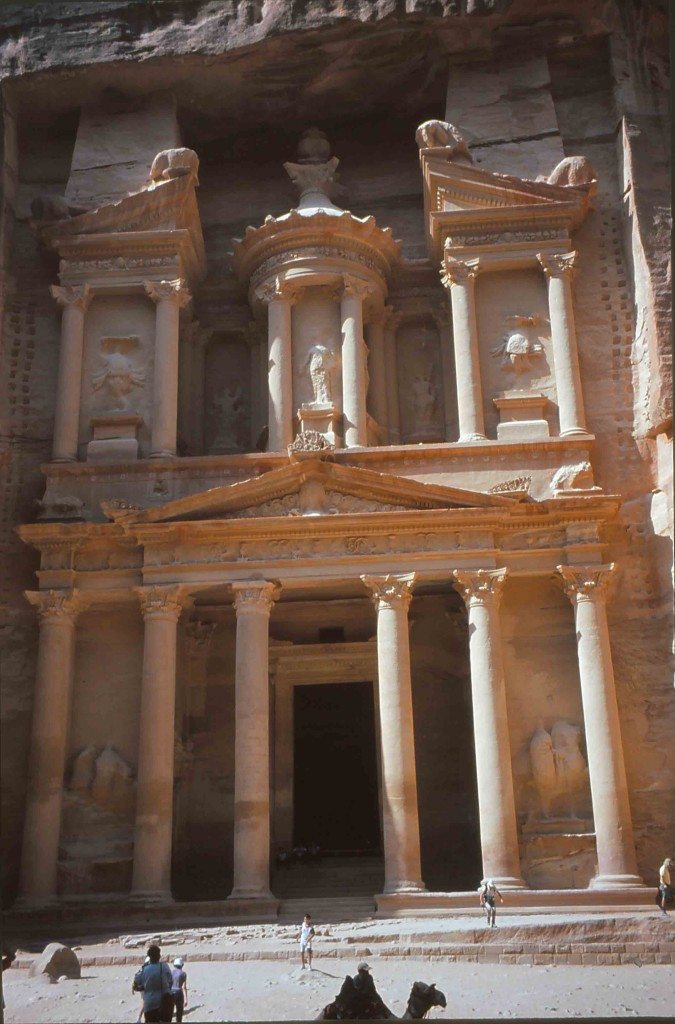

Like Burckhardt, your excitement rises the further you go into the Siq, your footfalls echoing off the canyon’s walls. Then there is the Bucket List moment when you finally turn a corner and the full majesty of the el-Khasneh (the Treasury) comes into view. This structure, carved from the cliff face, is the most ornate and best-preserved of all the monuments at Petra, and even if you have done the trip through the Siq a dozen times, it never fails to impress.

At the foot of the el-Khasneh the area opens up and is often crowded with tourists, some shops and gaily dressed camels. Take note of recent excavations at the foot of the el-Khasneh that show us that the ground surface on which we walk today is several metres higher than in antiquity. Looking down through some grates you see a lower register of buildings completely covered by the debris of numerous floods that have carried gravels down the Siq to be deposited at the foot of the el-Khasneh.

From the el-Khasneh, I recommend that you follow the flow of visitors towards the rock cut theatre but then turn to your left and begin the ascent to the High Place of Sacrifice. The climb is worth it, you not only leave the maddening crowds and Bedul touts behind but, on reaching the rock cut platform, you have a stunning view over the entire city.

At the top you’ll notice the so-called ‘God-Blocks’ that are unadorned pillars of stone representing the Nabataean deities, as well as numerous altars and basins to collect the blood of sacrificial offerings. The concept of holy mountains is a very Near Eastern thing. The Sumerians in flat Mesopotamia had to build artificial mountains that we call ziggurats on which to pray while at other sites such as Baalbek in northern Lebanon, altars consist of towers of stone on which the priests would have officiated. With mountains readily available, the Nabataeans could pray to Dushara from the top of actual mountains and one can only imagine the ceremonies taking place with the rich trading city laid out panoramically below them.

From the High Place of Sacrifice keep heading west as you descend past several lovely tombs towards one of the few free-standing buildings seen today: the Qasr el-Bint (literally the Fort of the Girl) that takes its name from a local legend. This building was a Nabataean temple with stairs giving access to a flat roof on which the ceremonies would have taken place, in keeping with the holiness of mountains but for those not wanting to walk up actual mountains!

In the heart of the city

Now you are in the heart of the city and back amongst the crowds. There are cafes and a restaurant here where you can revive somewhat before your next exploration. Although Petra was entered on to the World Heritage List administered by UNESCO in 1985 there remain issues.

While not on the List of World Heritage in Danger, there are concerns about Petra both in terms of how to preserve the friable sandstone monuments and how to reconcile the needs of the local Bedul, the wider Jordanian community and increasing tourist numbers.

The Jordanians know what a jewel they have in Petra and the government has increased staff numbers which has enabled campaigns of inspection and control, as well as strategies to manage tourist access and local community involvement, including the location and design of community-managed shop/kiosks. While the aim is there, it is hard to reconcile this with the needs of the local Bedul who rightly see Petra as ‘theirs’ and as a major source of income. This has resulted in a sometimes chaotic scene in the central city where children pester you to buy dubious souvenirs, or to ride their donkey/horse/camel, and ramshackle shops seem to sprout up in any available niche. It is a fine line that needs to be walked in these circumstances. Ancient sites benefit by having a bit of action and local colour. However, there is a limit and sometimes the tumult can get a bit much at Petra.

Al-Deir

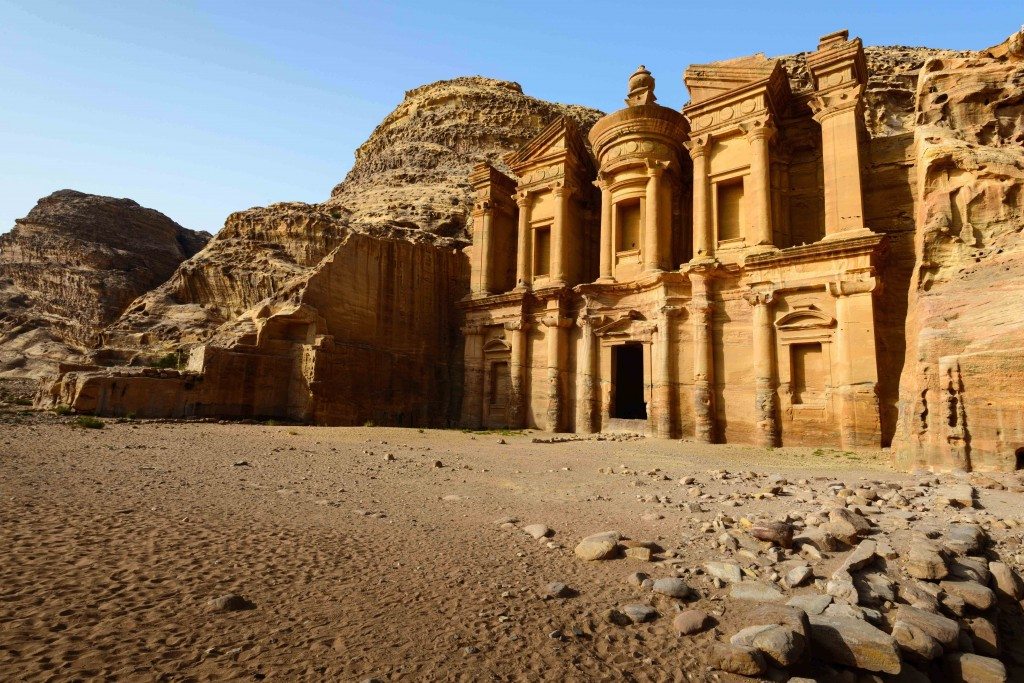

Our next destination should be the al-Deir or the monastery. The path to this magnificent monument starts behind the government restaurant and winds its way up into the hills to the west. The site received its name from a cave that is known as the Hermit’s Cell and when you get there you can well imagine what a great location it would have been for a medieval monk to secrete himself away from society.

Al-Deir is one of the largest monuments at Petra and displays the typical classical façade. While at first glance the style seems very Roman with columns (note the unique Nabataean, horned, capitals in use at the al-Deir in contrast to the fine Corinthian capitals at the el-Khasneh), pediments and other accoutrements, in fact, scholars tell us, the architectural style is classical but influenced from the Alexandrian school in north Africa rather than from Rome itself.

At the al-Deir you can clearly see the ubiquitous broken pediment that characterises many monuments at Petra and the massiveness of the construction leaves you gob-smacked; and not least you are confounded about how the Nabataeans chose the right location where the stone would allow the carving of such an edifice and the technical skill (akin to a sculptor) of visualising the finished façade before construction began.

While at the al-Deir, before you retrace your footsteps back to the central city, take some time to walk further to the west. Here, a short distance away, you will reach the edge of the escarpment where several small altars have been carved from the mountains with, weather depending, breathtaking views over the southern portion of the Jordan Valley, the Wadi Araba.

Once back in the central city, if you have followed this itinerary, you will be tired and ready to head back to your hotel in Wadi Musa. Remember that the entrance is a good 4 km from Qasr el-Bint and it is mostly uphill, although at a gentle gradient. As you head back to the entrance you walk along the Colonnade Street or Cardo of the ancient city which has portions of paving preserved in places and the foundations of a civic arch. You may well succumb to the constant pestering to take some form of animal transport from Qasr el-Bint to el-Khasneh but make sure you agree on a price and stick to it (a common ploy at the end is for your chaperone to say: “yes, that price was for me, but what about something for my donkey/horse/camel!”).

A second day’s visit

As you move along the Cardo there are several other important monuments that could either be visited now or, as I would recommend, on a second trip into Petra (your ticket allows two days’ of visiting that most people feel is a minimum to fully appreciate Petra). First, on your right, are the foundations of the Great Temple, painstakingly excavated by Brown University professor emerita Martha Sharp Joukowsky over many years. Although much ruined, this 7560 m squared precinct is comprised of a propylaeum (monumental entryway), a lower temenos, and monumental east and west stairways which in turn lead to the upper temenos, the sacred enclosure for the temple proper. This building is a blend of different cultures and uses elephant head capitals, frescos, and elegantly carved pilasters and capitals to great effect.

Continuing further on, you may notice a structure with a modern roof off to your left. In 1990 Kenneth W. Russell discovered the remains of a Byzantine era church on the north slope of the Colonnade Street, the excavation of which was roofed to protect the finds. The church contains beautiful mosaic floors, marble screens, side rooms, a baptismal tank, and a room where 152 burnt scrolls, now known as the Petra Scrolls, were found. This archive belonged to one Theodore who was born in 514 CE and most of the documents date from a sixty-year period, roughly 528 to 588 CE, and comprise of property contracts, out-of-court settlements and tax receipts that provide a wealth of detail about everyday life during the Christian period at Petra.

The other group of monuments that you cannot fail to notice are the so-called Royal Tombs carved into the cliff-face off to your left. They require a climb of some steps to be reached but the Urn Tomb is believed by scholars to be the tomb of Nabataean King Malchus II who died in 70 CE or perhaps the tomb of Aretas IV (ca. 9 BCE to 40 CE) giving this group of monuments their name. Beside the Urn Tomb is the Silk Tomb, one of the prettiest of the Petra tombs due to the highly coloured sandstone into which it was carved, and the Palace Tomb, the massive façade of which is regarded as being influenced by the Roman Emperor Nero’s Golden House in Rome.

Other visits

Naturally we have only covered the highlights of Petra and the site is vast and would be rewarding for an enthusiast to spend days poking up this ravine and that to come across other rock-cut tombs and signs of Nabataean occupation. If your visit has the time, a trip to Little Petra or al-Beidha which is located a few kilometres from Petra and is easily accessible by taxi or rented car is recommended. This satellite suburb has its own mini-Siq and some finely preserved tomb façades. Most important is the aptly named Painted Tomb where fragments of the original covering layer of frescoed plaster remain to be seen. At al-Beidha you are likely to have the place to yourself and its small size makes for a more reflective visit following the vastness and grandeur of Petra itself.

A visit to Petra should be at least two days although a slightly exhausting visit, without many stops, could be completed in a day. Whatever you do, make sure that your visit is not one where you are just taken down the Siq to the el-Khasneh and then turned around again as happens with many visitors coming from cruise boats that bus people up from Jordan’s port, Aqaba. While this gives visitors their ‘wow’ moment, it does not do justice to the site.

Give yourself a couple of days to really soak in Petra and while the walk in and out of the Siq each day will test your endurance, think of how fit you will be as you fully explore one of the world’s great archaeological sites!

About the Author

Ben Churcher has a wide range of experience both as an educator, a traveller, a historian and an archaeologist. He holds an Honours degree in Ancient History, is Field Director at the University of Sydney’s excavations at Pella in Jordan and regularly gives public lectures on archaeological subjects for adults and students. Ben is Director of Astarte Resources, a company that produces and distributes educational material specialising in ancient history and archaeology and for the past 20 years Ben has led numerous tours throughout the Middle East, North and West Africa, Greece, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, China and Mexico. Ben lives in Queanbeyan, Australia.