There I stood, the slopes of Mt. Etna rising before me, the glorious Sicilian coastline reflecting the brilliant blue sky. I hadn’t taken a trip to Sicily, but was rather at the British Museum’s latest exhibition, Sicily: Culture and Conquest, gazing into one of the many photographic vistas that adorn the walls.

When I first entered the exhibit, two objects immediately caught my attention. On the left, a terracotta pot dating to 650-600 BCE. Its importance? It is the earliest known depiction of what is now the official symbol of Sicily, the triskelion (three legs in a circle). The influence of Greek culture on Sicily is still felt to this day it seems.

The other object was a wonderfully ornate ivory casket. Made by Muslim craftsman, it bears a long Arabic supplication, but also Christian iconography (two haloed saints holding crosses). The casket was most likely made as a gift for the Cathedral of Bari, and demonstrates Norman Sicily’s multicultural exchange and religious co-existence.

These two objects sum up the story of this exhibition, which focuses on two key periods of Sicilian history. The first half of the exhibition explores the island’s early cultures, primarily those of its Phoenician and Greek settlers. The second half explores the role of Sicily’s Norman rulers in creating a period of vibrant cultural exchange.

The exhibition is divided into five key areas and runs from the 21st April until the 14th August (more info below).

Ceramic Dinos with Triskelion

Ceramic dinos with triskelion, Fired clay, Palma di Montechiaro, Sicily, c.650–600 BC. Museo

Archeologico Regionale Di Agrigento © Regione Siciliana

Sicily’s First Inhabitants

This period is conjured as one of myth, monsters and mysteries. A curious tomb door presents almost alien imagery, a terracotta basin alludes to a long-lost religious rite, and a Phoenician mask cuts a gruesome grinning image. These decidedly human artefacts are contrasted with how the Greeks viewed the first inhabitants of Sicily. Thucydides, the famous Athenian historian, wrote that the earliest inhabitants of Sicily were the famously barbarian Cyclopes, and the equally barbarian and cannibalistic Laistrygones (Thuc.6.2). For the Greeks, the earliest settlers of Sicily belonged to the realm of myth, whereas for us, while the earliest settlers of Sicily are still shrouded in mystery, their material culture shows a concern and care for death that is less mysterious than it is universal.

Gold Libation Bowl

Gold libation bowl decorated with six bulls, Sant’ Angelo Muxaro, c.600 BC © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Rise of Greek Sicily

As a self-professed philhellene, this was perhaps my favourite section of the exhibition, which looks at monumental architecture, chariot-racing, war, and the Sicilian tyrannoi who funded it all. It paints Sicily as a region of antagonistic cities, but a region which commanded a lot of power within the wider ancient world. Despite this, the monumental temples of Sicily were primarily of local stone, since importing foreign marble was very expensive (the island did not have its own local supply). The value attached to marble is witnessed through a fragmentary marble tomb relief of the 5th century, which shows signs of being reused and re-carved.

Sicily’s fortunes through the Hellenistic period were also explored in this section. Of particular interest to me was how Sicily developed its own style of pottery in order fill the gap left by the decline of Athenian red-figure pottery. A funerary vessel from Centuripe shows an eros flying towards a central seated figure flanked by two standing figures. The bright yellows and blues set on a vibrant pink background mark this as a truly Sicilian development.

Limestone head from a temple Selinous, Sicily, c. 540–510 BC. Museo Archeologico Regionale A Salinas, Palermo, © Regione Siciliana.

1,300 Years, 6 People

With the rise of the Roman republic, Sicily’s autonomy began to wane. Rome’s war against Carthage, and subsequent alliances and sieges all influenced the fate of Sicily, as she became the first province of Rome. Sicily nevertheless had great importance as the ‘granary of Rome’, in fact, the export of grain from the island was blocked on two occasions by politicians wishing to excerpt their power and influence over Rome. As the centuries progressed, Sicily was conquered by a number of peoples. First, the Vandals in 468 CE, then Odoacer, King of Italy, in AD 476. The Ostrogoths conquered Sicily in 493 CE, followed by the Byzantines in 535 CE. From the 660s CE, numerous Arab raids were made on Sicily, before the long Arab conquest of Sicily from 827-965 CE. It was then in 1061 CE, that the Normans began their conquest of Sicily.

As is the nature of such a condensed section, the objects on display act as foci for key events or changes to society that occurred during this long period. A Roman ship’s bronze battering ram acts as a witness to the decisive Battle of Egadi Islands, and a collection of humble lamps illuminate the different religions that were worshipped on Sicily. The carefully selected objects accelerate you from Greek Sicily to Norman Sicily.

Bronze Rostrum

Bronze rostrum from Roman warship, from the seabed near Levanzo, Sicily. c.240 BC.

Soprintendenza del Mare © Regione Siciliana

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily

Under their Norman Kings (the emphasis being on Roger II), Sicily developed into a world power, rivalling the might of the Byzantine Empire, the Egyptian Caliphate, and the Papal States. This Mediterranean island was now home to Byzantine Greeks, Muslim Arabs, Jews, and Christian Normans, creating a crucible of cultural collaboration.

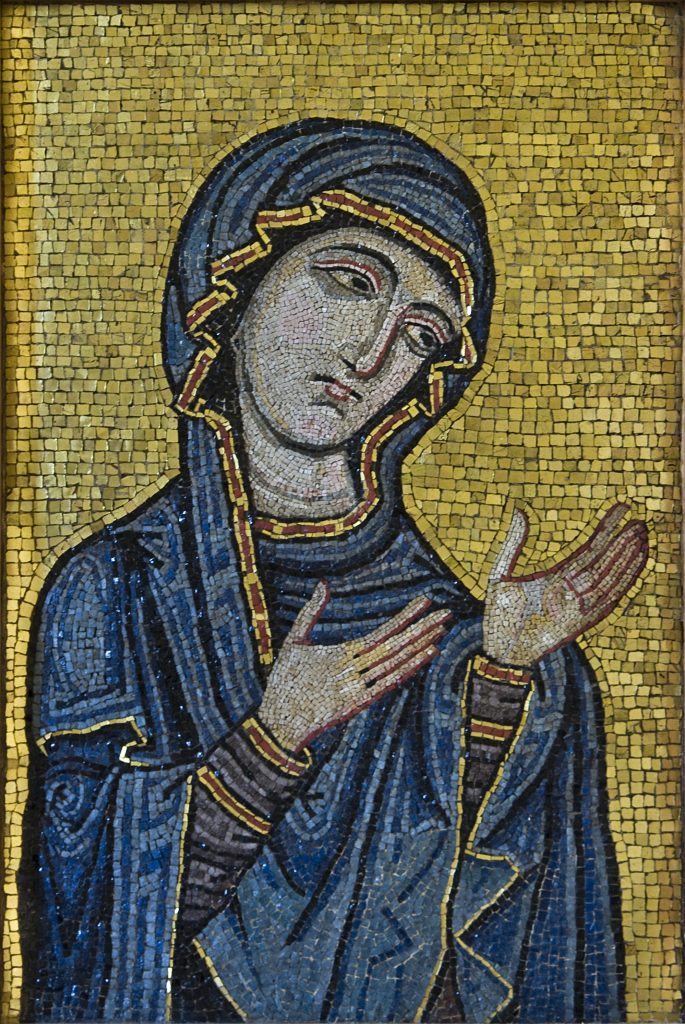

Arabic influences are most strongly seen in the Arab-Norman architecture of Palermo, recently added to UNESCO’s World Heritage list. A photographic vista captures the skyline, and surviving architectural artefacts illuminate the interior splendour of these buildings. In contrast to Arabic inspired arches and geometric patterns is a mosaic of the Virgin Mary, originally from the Palermo Cathedral, which alludes to similar Byzantine forms.

While Roger II was a great benefactor of the arts, he was also a patron of the sciences. One of the oldest copies of a map created by Al-Idrisi, the Arabic cartographer, is on display, showing Roger’s concern over scientific investigation and his interest in the wider world. This scientific interest was continued by Roger II’s grandson.

12th century mosaic Byzantine-style mosaic showing the Virgin as Advocate for the Human Race. Kept at Museo Diocesano di Palermo, originally from Palermo Cathedral, c.1130-1180 AD. Museo Diocesano di Palermo Please note this object will only be on display until 14 June 2016

An Enlightened Kingdom

Roger’s grandson, however, was no ordinary citizen. This grandson grew up to be Frederick II, the Holy Roman Emperor who stationed his royal court at Palermo. Not only does this section of the exhibition continue to explore Arabic influences on Norman Sicily, it also explores how Frederick II emulated the grandeur of the Roman Empire. This can be seen in the way his coins mimicked the earlier mints of the Roman Emperor Augustus, and in a colossal marble bust which depicts Frederick as Augustus (or possibly Constantine).

The grandeur of this exhibition ends almost as abruptly as Norman Sicily did, for Frederick II died without an heir, and the kingdom of Sicily would never again maintain the level of autonomy that it once had. The final object on display, Antonello da Messina’s ‘Virgin and Child’, acts as an epilogue, a beacon of Sicilian artistic independence, soon to be outshone by the wildfire of wider European renaissance.

Bust of Frederick II

Marble bust of Frederick II, Italy, 1220–50 AD. Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Rome. ©

H. Behrens, DAI Rom

Having outlined the core elements of the exhibition (and leaving much for the reader to discover for themselves!), I will now highlight some of my favourite features and objects.

FAVOURITE DISPLAY FEATURES

A lot of thought has gone into how the variety of objects are actually are displayed. A mirror was placed behind a Greek storage jar in order to see its rear decoration, so make sure to lean to the side and look at the rear reflection! Another favourite was a map of Sicily with coins from the various poleis placed where that city was. This gave a clear representation of each city’s unique iconography and visual allusions, but also of the unified medium in which their messages circulated. In the Norman section, the famous wooden honeycomb ceiling of the Cappella Palatina is reproduced on a backlit display on the ceiling, providing you with a perspective not too dissimilar to the one you would get viewing it in situ. I also really appreciated the photographic vistas of Sicily that decorated the walls, they really brought the essence of the Island to life.

Good news for anyone visiting with children too, various objects include a blue display marked by a gorgeion asking fun and engaging questions that make one think about the object for a little longer than a quick glance in a display case might. For example, I was asked to play ‘spot the difference’ with the three goddesses that decorate the below altar.

Terracotta Altar with three women

Terracotta altar with three women and a panther mauling a bull. Gela, Sicily. C.500 BC. Museo Archeologico Regionale di Gela © Regione Siciliana.

FAVOURITE OBJECTS

My favourite object in the exhibition is the Etruscan helmet dedicated by Hieron I of Syracuse at Olympia after a military victory. One of my favourite works of Greek literature happens to be Xenophon’s, Hiero, a fictional dialogue between the Sicilian tyrant and the poet Simonides. Being able to see some solid remnant of the tyrannos, and the way he interacted with the wider Greek world was particularly exciting. My second favourite object is the Sicilian temple drainage system because of its combination of aesthetics and utility. Each drainage spout is decorated in a different polychrome pattern, and in torrential rain the cascading waterfall that would have surrounded the temple would have been a spectacle in itself.

These are my personal favourites, different features and objects will appeal to different people… I leave you to decide what your favourite is! If you want a sneak-peek at some of the objects on display, including the helmet dedicated by Hieron I, check out the below video, where the exhibition’s curators discuss some of the objects that are on display in more detail!

[embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EOddeFRrQ7c[/embedyt]

Sicily: Culture and Conquest offers a fascinating insight into the island’s two key periods. The objects not only speak for themselves, but they communicate with each other, the monumental temples of Sicily’s Greek tyrannoi foreshadowing the architecture of Sicily’s Norman kings. Of particular interest is the exhibition’s allusion to a world that isn’t often heard today, Islamophile, for that is what the Norman Kings were. In the second half of the exhibition, the viewer is definitely encouraged to reflect upon how our modern multiculturalism measures up to the Norman’s.

Sicily: Culture and Conquest delivers what it promises, and is the culmination of three years of preparation and collaboration with twenty-four different museums, the Regione Siciliana, Assesessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identita Siciliana, and Julius Bar, who sponsored the exhibition. “Sicily: Culture and Conquest” is recommended viewing for everyone able to visit. Further information about booking and opening hours is provided below.

Sicily: Culture and Conquest

21 April – 14 August 2016

Room 35

British Museum

Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG

Sponsored by Julius Baer

In collaboration with Regione Siciliana, Assessorato dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana

Tickets £10.00, children under 16 free

Group rates available

Booking fees apply online and by phone

britishmuseum.org/sicily

+44 (0)20 7323 8181

Opening times

Saturday –Thursday 10.00–17.30

Friday 10.00–20.30

Last entry 80 minutes before closing time.

The British Museum is also running a series of lectures and public events throughout the duration of the exhibition. More information is available from their Press Office or via:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/whats_on/exhibitions/sicily/events.aspx