Sparta was one of the most important cities in ancient Greece, and the stories of its heroic warriors continue to be retold through modern films and stories. However, the popular image of Sparta propagates a version of Sparta, our version of Sparta, and this is often quite removed from the ancient sources and idealised. As such, this post includes some interesting facts (and theories) about ancient Sparta that you might not know, enjoy!

The first female Olympic victor was Spartan

Cynisca is someone more people should know about. She was the first woman to win at the Olympic games. She did this some 2412 years ago in 396 BCE (and again in 392 BCE). The event that she won both times was the four-horse chariot race.

To qualify this achievement, she did not actively race in the event herself, but, as was the custom, she trained and bred the horses that competed, and funded the chariot and its racer. That should by no means diminish Cynisca’s achievement though. The four-horse chariot race was a very aristocratic and highly praised event. Only the wealthiest of men could. In fact, women were not allowed within the sanctuary of Olympia while the games were on. For a woman to then win this event would have caused quite a stir!

However, while it is easy for us to see this first female victory and look favourably on it, not everyone in the ancient world would have. Xenophon, in his biographical work on Agesilaus II (Cynsica’s brother), claims that Agesilaus encouraged his sister to enter the chariot race in order to discredit it as a sporting event (it required no skill, only wealth). If this was Agesilaus’ intention, it did not work, and Cynsica’s achievement would later be praised in Sparta, where a hero shrine was established for her (Pausanias, 3.15.1).

In fact, we can still read Cynisca’s victory poem, dedicated at Olympia with a bronze statue for all to see:

The fragmentary statue base and victory poem of Cynisca.

Spartan kings are my fathers and brothers.

I Cynisca, victorious with the chariot of swift-footed horses,

Have erected this statue. I announce that

I am the only women in the whole of Greece to take this crown.

Apelleas, son of Kallikleos made [this statue].

298, rather than 300, Spartans, died at Thermopylae

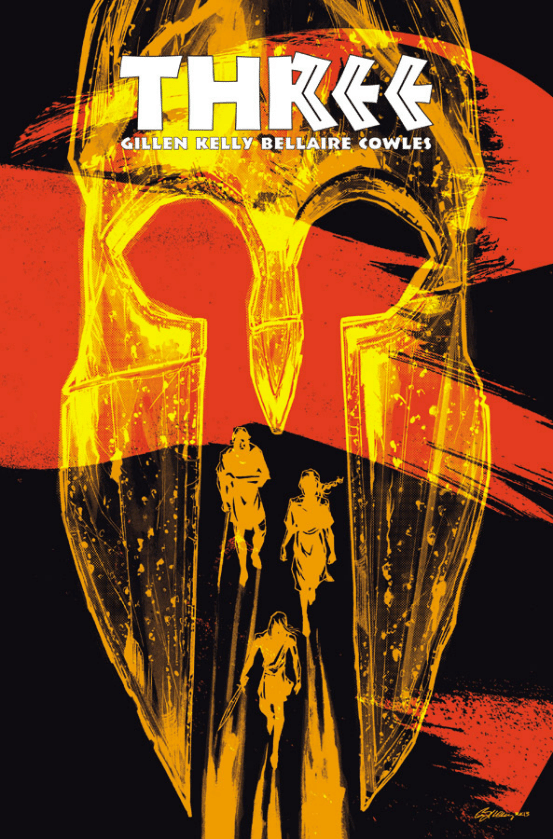

300 is probably the first thing that most people associate with Sparta, both the 2006 Zack Snyder film (based on the graphic novel), and that 300 Spartans fought at the infamous battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. However, that is not quite true…

Two of the Spartans sent to Thermopylae did not die in the battle. Herodotus informs us that two Spartans, Eurytus and Aristodamus, were being treated for serious eye infections when they heard that the Persians had found a way around the pass so as to attack the Greek forces. Eurytus bravely charged into battle and died. Aristodamus stayed behind. He returned to Sparta with great shame (he later redeemed himself at the battle of Plataea where he died).

The second Spartan who avoided death at Thermopylae was Pantites. He was away at the time of battle bringing a message to Thessaly. When Pantites return to Sparta, he was so ashamed not have been in the battle that he hanged himself!

So, there we have it, 300 Spartans went to Thermopylae, and only Aristodamus and Pantites came back alive (though not for long).

Aristodamus and Pantites nowhere to be seen…

You can read Herodotus’ account of the Battle of Thermopylae here.

The Spartans enslaved an entire population, the Helots

The darkest aspect of Sparta’s success was that, ultimately, it was enabled by the dehumanisation, subjugation, and enslavement of an entire people, the Helots, a population of Greeks who lived in Messenia.

The Helots were, in effect, agricultural slaves. The Spartans used them to work the land and provide food for the Spartan state. Helots were also recruited to fight for the Spartans when needed. However, there was a constant fear that the Helots might rise up again the Spartans (they outnumbered them massively).

As such, each year the Spartans ritually waged war on the Helots. One of the ways this ritual war manifested itself was through the Krypteia. The Krypteia was a sort of Spartan secret police, a body of young Spartan men chosen for their military potential and prowess. They were sent out to literally hunt and kill the strongest and most dissident of the Helots.

The most infamous Spartan act against the Helots occurred in 425 BCE and is related by Thucydides (4.80.3-4):

Prof. Stephen Hodkinson from the University of Nottingham acted as historical consultant for the graphic novel Three, which tells the story of three Helots’ struggle against the Spartan state. A series of footnotes at the end of novel help explain the various sources that inform the aspects of helotage and Spartan society that appear throughout. A gripping and illuminating story that I highly recommend!

“Indeed fear of their [the Helots’] numbers and obstinacy even persuaded the Lacedaemonians to the action which I shall now relate, their policy at all times having been governed by the necessity of taking precautions against them. The Helots were invited by a proclamation to pick out those of their number who claimed to have most distinguished themselves against the enemy, in order that they might receive their freedom; the object being to test them, as it was thought that the first to claim their freedom would be the most high spirited and the most apt to rebel.

As many as two thousand were selected accordingly, who crowned themselves and went round the temples, rejoicing in their new freedom. The Spartans, however, soon afterwards did away with them, and no one ever knew how each of them perished.”

Helen of Troy was really Helen of Sparta

Helen of Troy, the face that launched a thousand ships, was from Sparta. The importance of Helen’s Spartan origins can be seen in the Menelaion at Therapne, one of the earliest hero shrines in ancient Greece, dating to c.700 BCE.

Helen was worshipped at the Menelaion (along with Menelaus and the Dioskouroi, Helen’s husband and brothers) by Spartan maidens, but she was also worshipped by men too, probably in the form of a goddess of fertility. The earliest inscription to Helen from the Menelaion sanctuary dates to c.650 BCE and is from Deinis (a male name), who dedicated a bronze meat-hook.

Helen had another shrine within the city of Sparta proper, where the Spartan Helenia festival was likely held, it is possible that Theocritus refers to the aetiology of this festival in his 18th Idyll. However, the worship of Helen, clearly influenced in someway by the mythology of the Iliad, is a complicated topic, and worship of Helen occurred outside Sparta too.

So remember, there is much more to Helen than the woman who went with Paris to Troy!

Sparta was a hub of music and poetry in the Archaic period

Early Sparta was not just famous for its military, but also its music. Poet-musicians travelled from far afield to work in Sparta. The semi-legendary musician Terpander (from Lesbos) was credited with establishing the first musical contests in Sparta. Alcman (from Lydia) was renowned throughout the ancient world for his ritual songs about Spartan maidens. Additionally, Tyrtaeus (a native Spartan) composed political and military elegies that spurred the Spartans on against their war with the Messenians (to name just three).

The Spartans were so defensive of their musical heritage, that they supposedly banned all Helots from performing the works of Alcman and Terpander, and forced them to sing low and baseless songs instead. Plutarch relates the story thus (Lyc. 28.4-5):

And therefore in later times, they say, when the Thebans made their expedition into Laconia, [4th century BCE] they ordered the Helots whom they captured to sing the songs of Terpander, Alcman, and Spendon the Spartan; but they declined to do so, on the plea that their masters did not allow it, thus proving the correctness of the saying: ‘In Sparta the freeman is more a freeman than anywhere else in the world, and the slave more a slave.’

This is just a brief insight into the way that music may have been used within ancient Sparta to divide and define different societal groups, but it is also a story that emphasises the great importance that Spartans attached to their musical heritage. Understanding the role of music within Spartan society is the main aim of my PhD (and is perhaps one the reasons why this topic is on this list!)

Spartan hoplites probably didn’t have lambdas on their shields

The popular image of Sparta is one of a state of military muscle men decked out in red cloaks and hoplite shields emblazoned with the Greek letter ‘lambda’ Λ, which stood for Lacedaemonioi (think of Gerard Butler).

However, the only evidence that we really have for this comes from a rather dubious and late source, the 9th century CE lexicographer Photius, under the entry for the Greek letter ‘lambda’:

L was written by the Lacedaemonians on their shields, like the Messenians [wrote] M [on theirs]. Eupolis: “He took fright at seeing the lambdas flash out.”

Eupolis was a 5th century BCE Athenian comic poet. Because Photius’ quotation of him is removed from the wider plot of his play (and we have no way of telling which play this quote is from), it is difficult to confirm or deny whether it actually relates to a Spartan actuality, or some ongoing joke specific to the plot of the comedy.

When we look at Spartan self-representations of hoplites, the image is very different. A vast number of votive lead figurines come from the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia in Sparta, and date from c.650 BCE to c.350 BCE, many of these lead figurines represent warriors with shields, none of which can be seen to have lambdas on them, but rather various animals or geometric patterns.

A fragmentary lead figurine depicts a Spartan hoplite with rosette pattern on his shield

This is not to say the Spartans at some later point did not adopt lambdas on their shields, or that no Spartan ever had a lambda on their shield (we know of other poleis that used the initial of their city on their shields). It just goes to show that material and literary evidence for the ancient world can often provide very different evidence and that the two need to be taken hand in hand for a fuller understanding of the ancient world.

They used iron rods, rather than coins, as currency

Money, in the form of coinage, was a great political tool in the ancient world. Cities could patriotically proclaim the image of their state to the world, and rulers could reinforce their legitimacy. Most famous is the Athenian owl or the Roman mints that proudly proclaimed the twins Romulus and Remus. However, Sparta did not have a coinage (until King Areus, 309-265 BCE minted silver tetradrachms, only four of which have survived).

Instead, it is thought that for internal dealings Spartans would have used iron spits as a form of currency. This story is related by Plutarch in his Life of Lycurgus:

In the first place, he withdrew all gold and silver money from currency, and ordained the use of iron money only. Then to a great weight and mass of this he gave a trifling value, so that ten minas’ worth required a large store-room in the house, and a yoke of cattle to transport it. When this money obtained currency, many sorts of iniquity went into exile from Lacedaemon. For who would steal, or receive as a bribe, or rob, or plunder that which could neither be concealed, nor possessed with satisfaction, nay, nor even cut to pieces with any profit? For vinegar was used, as we are told, to quench the red-hot iron, robbing it of its temper and making it worthless for any other purpose, when once it had become brittle and hard to work.

In the next place, he banished the unnecessary and superfluous arts. And even without such banishment most of them would have departed with the old coinage, since there was no sale for their products. For the iron money could not be carried into the rest of Greece, nor had it any value there, but was rather held in ridicule.

An iron spit from Sparta, their early currency?

However much this story is in the realm of myth and fantasy, it seems that there might have been some basis to it. Excavations in Sparta have revealed a number of iron spits, now heavily corroded. If nothing else, then, it seems that these peculiar iron rods might have been the iron money to which Plutarch was referring. Such currency would have been long out of use in the 1st century CE when Plutarch was writing, but perhaps it was still on display in various Spartan sanctuaries, where priests might indulge a traveller with a tale about the great age of Lycurgus.

Spartan mercenaries fought for the last Egyptian Pharaoh

Another myth that continues to lurk about ancient Sparta is that it was a deeply xenophobic society. While this is true to some degree, it makes it easy to forget that Sparta was involved with people and places far away from Greece. This next story serves to illuminate one of Sparta’s more remarkable international dealings.

Cynisca’s brother, King Agesilaus II, spent his final days leading a mercenary army in Egypt, having spent his earlier years proving himself as a military leader of great skill (most famously against in the Persians in 396-4 BCE).

In 362/1 BCE, at around 80 years of age, King Agesilaus II (Cynisca’s brother) was summoned by Pharaoh Nectanebo I to lead his Egyptian forces against the Persians (Egypt had been conquered by the Persians in 525 BCE but then later regained independence). Agesilaos saw this as a good opportunity to increase diplomatic and trade relations with Egypt, as well as to fill the coffers of an otherwise declining Spartan state and punish the Persians for their previous actions against the Spartans.

What happened next can only be described as political chaos.

Shortly after Agesilaus arrived in Egypt a group of Nectanebo I’s Egyptian troops rebelled against the Pharaoh, and the rest then deserted him. Nectanebo I fled for his life while he still could. This left Agesilaus with no obvious employer, and no guarantee of payment. Agesilaus was then in the position of deciding which of these two groups of Egyptians to support. Agesilaus chose the right side, helping to secure Nectanebo II as Pharaoh (Nectanebo II would be the last native Pharoah of Egypt). Nectanebo II paid Agesialus for his services, and the Spartan king set about returning home. But it was a journey he was never to complete. Agesilaus died peacefully on the way home at Cyrene in North Africa. His body was transported back to Sparta.

Sparta was a tourist destination under the Roman Empire

It is often argued that after 371 BCE, when the Spartan army was defeated by the Thebans at the battle of Leuctra, Sparta was never the same again. In many ways this is true. The political independence of Sparta came into question with the rise of Macedon, the Achaean League, and then Rome, and Sparta’s army was never as strong as it was when fighting the Persians and the Athenians in the 5th century BCE.

The Romans in effect brought the myth of Sparta to a much wider audience, though, and it seems that the Spartans were more than happy to indulge these cultural tourists with tales and spectacles of ancient tradition. Even if some of these traditions were perhaps not so ancient, and more charlatan in nature.

The myths and excitement of what Sparta once was were capitalised upon. Many of the buildings of ancient Sparta that can still be seen today actually date from Roman Sparta. Perhaps the most obvious example of this tourism can be found at the sanctuary of Artemis Orthia.

One of the oldest sanctuaries in Sparta, dating perhaps as early as 800 BCE, Romans would gather around the old temple to witness the ancient tradition of diamastigosis. This tradition involved Spartan youths endured a ritual whipping in order to toughen them and placate the goddess (Artemis) Orthia. The event was famous throughout the Roman world, even Cicero attended the event! By the 3rd century CE, a large stone theatre had been built around the temple of Orthia, where crowds of tourists could revel at the bloody ancient Spartan ritual with ease.

A reconstruction of the Roman theatre built around the temple and altar of Artemis Orthia.

The Legend of Sparta

Sparta has had an enduring impact on popular thought and culture. The study of the reception of Sparta by other societies (including our own) has resulted in some very interesting works. However, if you ever find yourself in modern Sparta (and I would very much recommend this), take a minute to look at the street names, nearly everyone of them is named after a famous Spartan. Below is a short list of just some of these street names, and the famous Spartans who they honoured (mainly those who I didn’t have enough time to mention in this list)! Have a look on google maps and see which other famous Spartan people, places, and events you can see!

- Arhidamou – Archidamos II, King of Sparta, father of Cynisca. The king who formed the Thirty Year Peace with Pericles in 446 BCE.

- Chilonos – Most famously the wife of Cleombrotus II, Hellenistic pottery with the name Chilonis inscribed on it was found during the BSA’s excavations at Artemis Orthia.

- Kleomvrotou – Cleombrotus I, the Spartan king who was general at the catastrophic defeat against the Thebans at Leuctra in 371 BCE.

- Klearchu – Clearchus, a Spartan general and mercenary. He was outlawed by Sparta for governing Byzantium as a tyrant and disobeying orders. He then fought as a mercenary for Cyrus the Younger.

- Kleomenous – Cleomenes I, Spartan king from the late sixth to early fifth century BCE. He famously intervened with Athenian politics to promote oligarchy.

- Leonidou – Leonidas, the Spartan king who led the 300 Spartans and their allies at the battle of Thermopylae.

- Lisandrou – Lysander, the Spartan admiral who defeated the Athenians at Aegospotami in 405 BE. This brought about the end of the Peloponnesian War. Lysander also implementing the Thirty Tyrants at Athens.

- Vrasidou – Brasidas, the Spartan general who famously died during the capture of Amphipolis from the Athenians.

To find out more about Ancient Sparta

If you would like to find out more about ancient Sparta, here are some links to further reading, online and in print.

Online

- AHE content on Sparta

- The Centre for Spartan and Peloponnesian Studies at the University of Nottingham

- The British Museum Sparta Challenge

- Kyle, Donald G. “”The Only Woman in All Greece”: Kyniska, Agesilaus, Alcibiades and Olympia.”Journal of Sport History 30, no. 2 (2003): 183-203.

In Print

- Bettany Hughes, 2007, Helen of Troy: The Story Behind the Most Beautiful Woman in the World

- Paul Cartledge, 2003, The Spartans

- Sarah Pomeroy, 2002, Spartan Women

- Paul Cartledge and Antony Spawforth, 2002, Hellenistic and Roman Sparta: a tale of two cities

- Stephen Hodkinson, 2000, Property and Wealth in Classical Sparta

For anyone who really wants to delve into ancient Sparta I would recommend looking at this bibliography, it is now about 15 years out of date, but still has a lot of very important and relevant works.

For anyone who is interested – my PhD is concerned with how changes to Spartan musical practices can be seen in relation to wider changes in Spartan society, and how Spartan attitudes to music can help explore old questions concerning Sparta, ‘austerity’ for example, as well as the way in which the source material for Spartan music offers important questions regarding the methodology of studies on Sparta more generally, and for our understanding of ancient music.