About two thousand years ago, fifty thousand people filled the Colosseum in Rome to participate in one of the most fascinating and violent events to ever take place in the ancient world. Gladiator fights were the phenomenon of their day – a celebration of courage, endurance, bravery, and violence against a backdrop of fame, fortune, and social scrutiny. Today, over 6 million people flock every year to admire the Colosseum, but what took place within those ancient walls has long been a matter of both scholarly debate and general interest.

The murderous fights were a form of popular entertainment for the masses, both poor and rich alike. The ancient Romans had a morbid fascination with the gladiator, and still to this day, the gladiator remains an intriguing subject in academia and popular culture. To help separate popular myth from reality, we’ve assembled some of the most interesting facts about one of the most iconic figures of the Roman empire, drawn from Garrett G. Fagan’s Oxford Classical Dictionary article “gladiators, combatants at games.” Read ahead to see how much you know about Roman gladiators.

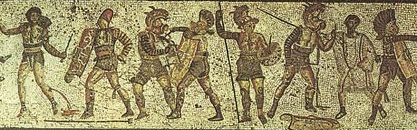

3rd century CE Roman floor mosaic depicting a retiarius armed with trident and dagger fighting against a secutor. From the Roman villa in Nennig, Germany. Photo © Carole Raddato.

Entertainment

1. According to modern scholarly interpretations, the gladiatorial games were perhaps vehicles of social control and functioned to distract the populus from recognizing their diminished autonomy under imperial rule. Gladiatorial games were a phenomenon in the Roman world, and both ancient and modern scholars have held different interpretations of the games and their place in Roman history. Some would argue that the games reflect typical Roman virtues, such as courage, endurance, and martial skill, while others, like Roman satirist Juvenal, thought that the games preyed on the Roman’s unhealthy obsessions with “bread and circuses” (Sat. 10.78–81). Modern interpretations consider the games distractions that kept the people subdued and unable to realize the real loss of power under the empire.

Objections

2. The educated elite opposed the gladiatorial events and saw them as mass entertainment for the lower classes. Their opposition, however, was never motivated by altruism. In fact, they were far less concerned about the lives of those participating in gladiatorial combat, who they viewed as worthless and deserving of their fate. Their opposition stemmed from what they saw as moral indolence and the indignities of indulgence.

3. Jews and Christians were likewise seemingly unconcerned about the victims of arena violence. Their arguments in opposition to the games focused on what they viewed as inherent idolatry, as gladiatorial show often occurred during pagan religious festivals, which featured idols and images of pagan gods.

Reputation

4. Gladiators were regarded as infames (people of bad reputation). Most gladiators were slaves, ex-slaves, or freeborn individuals who fought under contract to a manager. They were often ranked below prostitutes, actors, and pimps, and generally regarded as both moral and social outcasts.

5. Despite this, gladiators were the sex symbols of their day. Gladiators enjoyed quite a bit of popularity, especially from women – so much so that a name was coined for these ancient fan-girls (ludiae, or “training-school girls,” a term coined by Juvenal (Sat. 6.104).

6. Not all gladiators were men. It is not clear if women ever fought in the arena, but there is evidence that suggests female gladiators did exist. Roman emperor Domitian was said to stage fights between female gladiators and dwarves. Another notice suggests the ancient city of Halicarnassus hosted a fight between two female warriors named “Amazon” and “Achillia”. But while these fights may have very well taken place, they were likely spectacles put on for the emperor and were probably just a novelty.

“Bestiarii,” before 80 AD. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Monuments

7. Some gladiators were honored with monuments. Not all gladiators were simply killed and cast off. The more popular gladiators had gravestones and inscriptions that revealed their origins, careers, and views of their profession. Gravestones were quite expensive, and even more so if they were engraved. While the question remains if the sentiments left behind were their own, these epitaphs were often the only window into the personality of these warriors.

8. Gladiatorial bouts were originally part of funeral ceremonies. Gladiatorial exhibitions were originally associated with funerary commemoration. As the games’ popularity grew, so did their scale and finesse. One notable exhibition took place in 216 BCE, when 22 fights were held over three days to mark the death of a prominent senator.

Training

9. Gladiators were (mostly) recruited and trained, much like athletes are today. Gladiators were lived and trained in schools (ludi gladiatorum) under the watchful eye of their managers (lanistae). Willing gladiators worked under contract, while unwilling gladiators (usually slaves) were either bought by a ludus gladiatorum or condemned by the Roman courts to fight in the arena.

10. Death was an acceptable outcome, but not an inevitable result, of gladiatorial shows. Most depictions of gladiatorial combat often portray fights as a bloody free-for-all that usually ends with one participant brutally maiming the other, but that was not always the case. Since gladiators were skilled professionals, it would be a devastating economic blow to managers if they lost a member of their gladiatorial stock.

Controversy

11. The gladiatorial games were officially banned by Constantine in 325 CE. Constantine, considered the first “Christian” emperor, banned the games on the vague grounds that they had no place “in a time of civil and domestic peace” (Cod. Theod. 15.12.1). However, there is no evidence to suggest that the ban was implemented for humanitarian reasons. In fact, the would-be gladiators were sent instead to the mines to ensure a steady stream of labor. Further evidence suggests that the games had simply become too expensive and that the recent “Christianizing” of the empire had resulted in fewer combatants.

Featured image credit: “Colloseum” by Björn Fritz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Article originally posted on Oxoford University Press Blog ; reposted with permission.