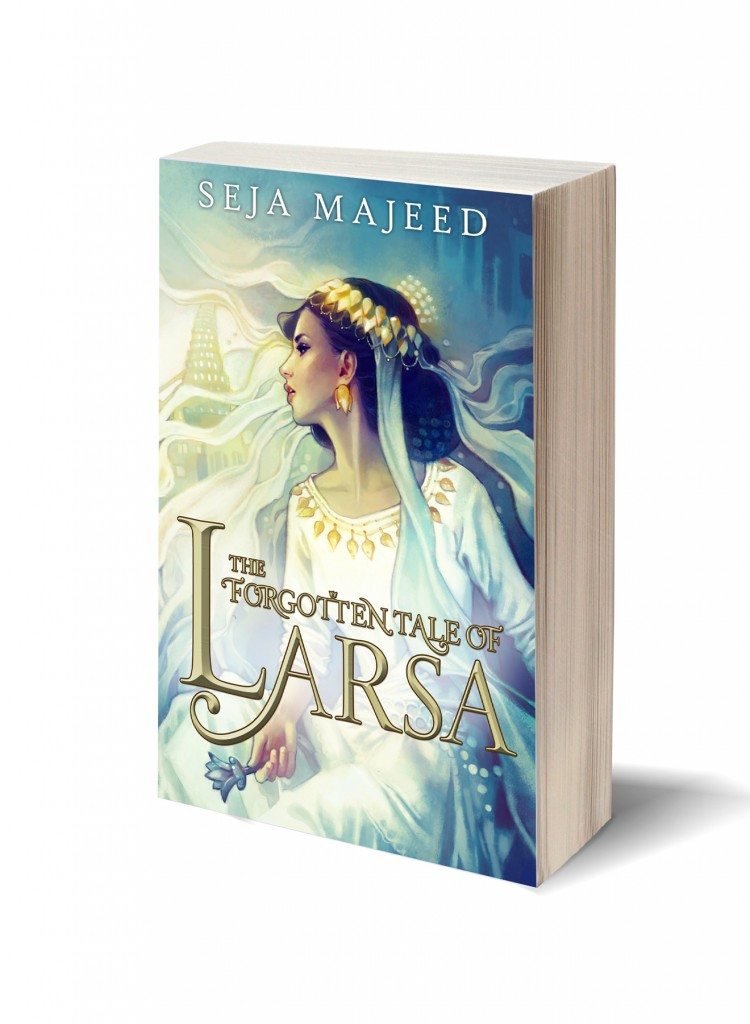

Born in Algeria to Iraqi refugees, Ms. Seja Majeed grew up in the United Kingdom, where her family claimed asylum. Impassioned by history, archaeology, and especially Iraqi culture, Seja yearned to be a writer. In her début novel for young adults, The Forgotten Tale of Larsa, Seja explores the themes of love, loss, change, and exile in an ancient Near Eastern setting. In this conversation with James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia, Seja relates the joys and struggles one faces in writing the “young adult novel,” in addition to her thoughts on the current perils facing Iraqi cultural patrimony.

JW: Ms. Seja Majeed, welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE)! It is a pleasure to speak with you about your new novel, The Forgotten Tale of Larsa, which debuted this summer. Congratulations.

I am interested to know what motivated you to write The Forgotten Tale of Larsa. Moreover, why did you decide to write a novel set in the ancient Near East? Does Near Eastern antiquity fascinate you?

SM: I have absolutely loved history since I was a child. I remember my father taking me to the British Museum in London; we would always go there together and take pictures. Whenever I was at the British Museum, I felt as though I were transported back to the empires of the ancient world. As I sat amongst the artifacts, staring at them with sheer wonder, I would imagine who built them and how they survived over the centuries. Without anyone seeing, I would rather cheekily touch the large statutes and imagine the people who crafted them; additionally, I would think about how they may have looked or what their names were.

JW: Given your background, as well as the challenges that you and your family endured as displaced Iraqis, I am not surprised that you have become a writer.

In the past, I have heard from others authors that writing for a young adult audience is terribly difficult. Would you agree? What specific challenges did you encounter as you wrote The Forgotten Tale of Larsa, and how were you able to overcome them?

SM: To be brutally honest, I never really thought about my audience as I wrote my novel, The Forgotten Tale of Larsa. I was writing for my own escapism, and I simply wanted to tell a story of tremendous love and loss. I think that helped me in the long run; writing is such a personal thing. If I consciously thought about my audience, I think it would have stunted my ability to write the narrative. All I was really doing was writing from my heart, and I wanted to remain true to it. Throughout my “writing journey,” I endured significant hardships, and for me it was a form of meditation: I would sit and lose myself in my imagination. It was the only place that I truly controlled. Somehow, it made me feel safe, but the process of writing also liberated me in many other ways. It is all rather difficult to put it into words, but as a writer, there is something so beautiful and exciting about crafting a fictional piece and finding freedom in one’s imagination.

What was the most difficult challenge during the writing process? I was actually quite happy with my “journey.” I had rewritten the story several times, and I had shown it only to one person: my sister. She knew about my characters, but no one else did – in fact none of my friends even knew I was writing a story, until I had finished it. My writing had improved so much, by the time I had completed it, the beginning had to be rewritten several times so as to keep the same, intact voice. By the end, I would actually refer to my narrative as “The never ending story.” I was 19 when I first started writing it. Now, seven years later, I have completed it, and I am in my mid-twenties!

Initially, when I was writing my novel, I had never considered that it would be for a “young adult” audience. In fact, I thought the book had too many dark themes — especially with murder, rape, and war — and I did not really feel it was suited to that kind of audience. Once the book was finished and sent to literary agents for their review, the feedback I got was that it should be aimed at a young adult audience. At first I took it as an insult, and I was completely against the idea of changing my target audience (even if it was constructive criticism).

I had worked endlessly on the narrative, and I wanted my story to be taken seriously by adults. In retrospect, however, I am so glad that my target market was changed to meet young adult readers; I think stories that are read during one’s childhood and teenage years tend to stay within your thoughts for a very long time. Many even go on to have an impact on your life. They become well loved, and they are remembered by the different generations that have gone on to read them.

I had worked endlessly on the narrative, and I wanted my story to be taken seriously by adults. In retrospect, however, I am so glad that my target market was changed to meet young adult readers; I think stories that are read during one’s childhood and teenage years tend to stay within your thoughts for a very long time. Many even go on to have an impact on your life. They become well loved, and they are remembered by the different generations that have gone on to read them.

I still remember reading Ronald Dahl’s writings — I loved The Twits and George’s Marvelous Medicine in particular. I can vividly remember the front covers and the weight of the books as I held them in my hands. If my book can in the slightest way instill a memory in someone’s mind, then I have achieved something I can really be proud of.

JW: Seja, I am curious to learn how you developed your characters: Did you conduct any research on the ancient world or mythology before writing? Also, did your characters change and develop over time, through various drafts or revisions?

SM: The characters really did come alive during the writing process. Unlike many writers, I never sat down and wrote a plan, I simply began to write. Each night, I would write a chapter, and I would work on it the next night. This carried on for a thousands of nights, as it took me many years to finally my novel. Although this might sound somewhat romantic, it often involved a lot of stress and distress. As the days progressed, the more powerful my characters’ voices became, the more clearly defined their identities were.

In one way or another, I found elements of myself trapped within all of them. I felt the bitterness of Sulaf through my own experience of unrequited love and lust; in Jaquzan, the Assyrian emperor, I saw my own fears, where evil is expressionless and shows no humanity even to the soul begging for mercy. And in Marmicus, I wrote about a love — one that was so pure, based on loyalty and companionship. This was something which I had always wanted to experience but had never known.

Each one of my characters signified a longing within me and a deep fear, too. However, Princess Larsa was special, and I did not see much of myself reflected in her personality; instead, she is a character in her own right. Occasionally, I saw glimpses of my mother within her; when my mother was pregnant with me, she experienced the torments of exile and murder. My mother witnessed countless horrors and deprivations as a refugee, and yet her bravery, resilience, and humanity became stronger. I believe she inspired me to write Larsa.

Writing a novel that was somewhat unplanned had its advantages, as well as its pitfalls. It meant that I was more focused on my writing style, as opposed to historical fact; it was only once the book was nearly completed that I realized that I had to go back and really start to fill in the gap of history. For example, it was not enough that I simply mentioned the name of the goddess Ishtar; I needed to find out what she represented, how she looked, how powerful she was in comparison to other gods, and so forth. I also had to research what a ziggurat looked like and the religious customs of the ancient Assyrians. Sometimes I tweaked historical facts, for instance, I knew that the Assyrians’ armor was made of leather, but I wanted to create a dramatic battle scene, and leather did not quite seem apropos. As to ziggurats, I knew that they were most likely made of mud bricks, but I referred to the Temple of Ishtar, in Babylon, as being made of stone. I think a professional historian would find these things a little bit trying, but I would hope it would inspire a younger audience to read more about the Assyrian and Babylonian Empires. Perhaps I might even receive a letter from one of my readers pointing out the historical alterations I made! I would gladly welcome some.

JW: The publication of The Forgotten Tale of Larsa comes as rising violence has returned to Iraq. In June, the forces of ISIS swept across the country, leaving chaos and destruction in their wake.

Many archaeologists and historians fear the worst for Iraq’s ancient monuments and artifacts. ISIS has already destroyed or damaged sites of historic importance across Syria and Iraq. As an Iraqi, what does Iraq’s rich cultural heritage mean to you? How can we educate the public to protect and preserve our wonders from the ancient world? Would you say that we have to start with children?

SM: As an Iraqi, it deeply hurts me to see the suffering of my homeland and my people. Iraq has such a rich history that belongs to us all — regardless of nationality — and it needs to be protected. ISIS has damaged and destroyed sites of historic importance, and if they are not stopped, they will continue their rampage, taking innocent lives and damaging other sites around the world. Such people cannot be reasoned with, and explaining the importance of the ancient world to them would be like trying to explain quantum physics to a Neanderthal — in short, it is a lost cause. (Although I like to think that Neanderthals had a little more intelligence.)

But Iraq’s rich cultural heritage has been in danger for years now; long before the formation of ISIS, Saddam Hussein stole many artifacts for his own pleasure, built on top of the ruins of Babylon, and he even inscribed his name the ancient city’s famed walls. What made matters worse was after the collapse of the Ba’athist regime, there was no plan set into motion for preserving and protecting these artifacts or historical sites. Ultimately, there was a significant amount of looting, and many of Iraq’s historic gems are lost forever.

So who will be held responsible for this? It angers me that so few seem to care about Iraq’s history despite its universal appeal and importance. Of course, it is fundamental to educate the public, especially children, to recognize the value of respecting and preserving our wonders from the ancient world. However, there is also a need to hold governments accountable for the damage done to ancient sites, not only in Iraq, but Afghanistan and elsewhere; we must encourage funding into archaeology and museums. I would also call upon the United Nations to hold responsibility in preserving the world’s cultural patrimony.

Having said that, I still believe there are many more sites within Iraq to be excavated and so much for the world yet to see, but due to the turbulent situation in Iraq, it seems highly unlikely that archaeologists will be able to resume work any time soon. If it were not for the British Museum, I sometimes wonder if there would be anything left from Babylon and Assyria to show the world.

JW: Seja, it took you nine years to complete your début novel. Are you ready to write another?

SM: I would love to write another, James! I have so many ideas bouncing around in my imagination, somewhat like protons and neutrons that may eventually collide and explode if nothing is done with them. But right now, I am still focusing on making this one a success. There is a lot of work that goes behind the scenes in marketing a book, and right now I am occupied with that.

JW: Thank you so much for speaking with us, Seja! We are eagerly looking forward to your next work of fiction, and we wish you many happy adventures in writing and research. Please be in touch.

SM: It’s been an absolute pleasure talking to you! Thank you for letting me discuss my book and for reminding the world of Iraq’s captivating history.

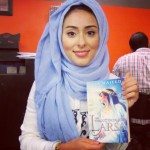

Image Key:

We thank Ms. Seja Majeed for sharing some promotional images with Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE).

Ms. Seja Majeed is an Iraqi-British author and businesswoman with an honors degree in law from Brunel University London and a Postgraduate diploma in Legal Practice from City University London. Majeed also has a diploma in Leadership Public Policy from the American University of Sharjah in the UAE. In 2012, Majeed was accepted into the highly competitive Graduate Working Scheme for Shell Petroleum Company, which enabled her to oversee several North Sea projects in Scotland. Thereafter, she was transferred to work on the Iraqi Majnoon project. Currently, Majeed lives in Dubai, UAE, and frequently travels to Iraq. Manjeed began writing her debut novel, The Forgotten Tale of Larsa, when she was just 19.

Ms. Seja Majeed is an Iraqi-British author and businesswoman with an honors degree in law from Brunel University London and a Postgraduate diploma in Legal Practice from City University London. Majeed also has a diploma in Leadership Public Policy from the American University of Sharjah in the UAE. In 2012, Majeed was accepted into the highly competitive Graduate Working Scheme for Shell Petroleum Company, which enabled her to oversee several North Sea projects in Scotland. Thereafter, she was transferred to work on the Iraqi Majnoon project. Currently, Majeed lives in Dubai, UAE, and frequently travels to Iraq. Manjeed began writing her debut novel, The Forgotten Tale of Larsa, when she was just 19.

All images featured in this interview have been properly attributed to their respective owner(s). Unauthorized reproduction of text and images is strictly prohibited. Special thanks is given to Ms. Seja Majeed for her time, consideration, and for sharing her images with us. Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt is to be thanked for her assistance in the editorial process. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE). All rights reserved. © AHE 2014. Please contact us for rights to republication.