Hadrian and his travels have often served as the guiding thread for my own travels. However, my recent trip to Turkey had a different focus, the Hittite civilization, with one of the highlights being a visit to the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara. After dazzling at the magnificent artifacts on display on the main floor of the museum, I discovered that there was also a section dedicated to the Roman period in Ancyra which featured, to my big surprise, parts of a statue of the Roman Emperor Hadrian.

Ancyra was the capital of the Roman province of Galatia, located in the highlands of central Anatolia (modern central Turkey). A Hittite settlement in the Bronze Age, Ancyra was later populated by Phrygians, Mysians, Persians, Greeks, and even Gauls from the Tectosages tribe. The latter, who had come all the way from what is now southern France, gave their name to the province. Ancyra became the capital of the Roman Province of Galatia in 25 BC. The Greek name for the city was Ankyra, which meant “anchor,” and is still recognizable in its modern form “Ankara.” The anchor became the symbol of the city and most of the coins from Ancyra have an anchor on them. The city minted coins of Nero, Nerva, Trajan, Antoninus Pius, Lucius Verus, Commodus and Caracalla, while one of the magistrates of the city, a certain Julius Saturninus, minted coins to honour Antinous. Like many cities of the eastern Roman empire, Ancyra enjoyed a period of considerable prosperity under Hadrian and became a major military base.

Commemorative coin minted by Julius Saturninus at Ancyra. Reverse: man standing in a sleeved tunic, eastern pants and a Phrygian cap, holding a scepter in one hand and an anchor in the other, crescent behind him, with legend IOVΛIOC | CATOPNINOC | ANKVPANOIC. CC BY-NC 4.0 American Numismatic Society.

The most important Roman monument of Ancyra is the Monumentum Ancyranum (the Temple of Augustus and Rome) which contains the official record of the Acts of Augustus, known as the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, an inscription cut in marble on the walls of this temple (see images here). This temple made Ancyra the neokoros (Temple Warden) of the Imperial Cult in Galatia.

Another monument of importance is the Roman theatre of Ancyra which is located on the northwest cliff of the Ankara Castle, southeast of the Temple of Augustus and Rome and the Roman baths. It was first discovered in 1982 and rescue excavations by the General Directorate of Cultural Heritage and Museum began in 1983. The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations continued the excavations until 1986.

The excavations uncovered a considerable portion of a typical Roman theatre dated back to early 1st century CE and 2nd century CE by different scholars. The remains of the theatre consist of the foundations of the cavea, the orchestra and part of its floor pavement, the lower part of the scaenae frons and stage building as well as two vaulted parados. Built on a natural slope of the hill, the theatre is approximately 50 x 43.5 metres across while the orchestra is about 13 metres in diametre. During the Byzantine era, the theatre was transformed into a pool which was used to stage water games. It is believed to have hosted between 3,000 and 5,000 people, a capacity typical of the small theatre typology among the theatres in Anatolia (like the ones at the Asclepeion of Pergamon and at Rhodiapolis).

The excavations also revealed a number of sculptural pieces that once adorned the stage building of the theatre. The finds include a high-quality female head in coloured marble, a large fragment of a nude statue carrying an armour, a colossal head of Silenus with wreath in high relief as well as fragments of a cuirassed statue of Hadrian.

A total of 26 fragments were discovered but only a few are exhibited in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in a section of the museum dedicated to the finds from the theatre.

The fragment of the top part of the head helped to identify the statue on account of the hairstyle. Hadrian’s hair is styled in luxurious curls and waves running from the back of his head to his forehead.

This portrait of Hadrian is likely to belong to the “Imperatori 32” type, one of the six sculptural types attributed to the extant corpus of Hadrian portraits by M. Wegner, a German specialist on Roman portraiture (a seventh type was added later on). Approximately 160 portraits of Hadrian have survived, and the “Imperatori 32” type was a type popular in Italy and in the provinces. The restrained carving of the forehead endows Hadrian with a youthful and idealised appearance.

Based on the reconstruction drawing (M. Türkmen – C. Zoroğlu) photographed at the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, the statue depicted Hadrian dressed in a cuirass and a short tunic under a military cloak (paludamentum) drapped over his left shoulder and falling down vertically over his left arm. The cuirass was decorated with the gorgoneion as well as two griffins confronting each other and partly covered by a cingulum, a military belt wrapped around the waist and tied at the front in a elaborate knot. His left hand was probably holding a spear. Next to his left leg, a tree trunk acted as support.

The other fragments of the statue include the lower front of the breastplate, a part of the shoulder belt and rivet, a part of the head of the gorgoneion, decorative pieces of the pteruge (the bottom of the breastplate), a part of the right and left leg, a part of right arm, as well as parts of the paludamentum.

The “Imperatori 32” type is connected with Hadrian’s becoming Pater Patriae (Father of the Fatherland) in 127-128 CE. The dating corresponds with the creation of a festival in Ancyra called the mystikos agon (mystic contest) for the worship of Dionysus. Hadrian as “neos Dionysos” (new Dionysus) was included in the ceremonies jointly with the god. He may have appointed the first agonothete (superintendent) of this mystic festival who was a prominent and wealthy Ancyran citizen called Ulpius Aelius Pompeianus. The erection of a statue of Hadrian in the theatre of Ancyra may be linked to the Dionysus festival.

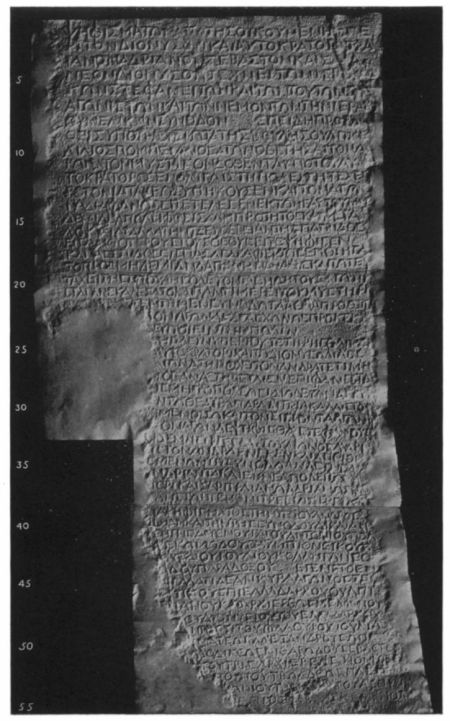

Hadrian passed through the city of Ancyra with his army on his way back to Rome in October 117 CE soon after he had been proclaimed emperor in Antioch. It may be on this occasion that Hadrian first allowed himself to be worshipped as the new Dionysus. One inscription from Ancyra testifies to Hadrian’s association with the mystic festival in the form of a honorific decree dated to 128 – 129 CE (IGR 3.209). The decree, inscribed on the pedestal made for a statue of Ulpius Aelius Pompeianus, included Hadrian as neos Dionysus in the ceremonies in Ancyra jointly with the god. It is now displayed in the Open Air Museum of the Roman Baths (see images here).

Decree of of the Association of Performing Artists dating to the reign of Hadrian (AD 117-138) in honour of Ulpius Aelius Pompeianus. Image in public domain.

In addition, one other inscription records that one of the benefactors of the festival should be honoured with two gilded shield-mounted images. One such image was discovered in Ankara in 1947 during foundation excavations in the district of Ulus, west of the theatre. These portraits, mounted on a round bronze shield (imago clipeata), were usually erected in civic buildings or public areas. This rare find can be seen in the Roman gallery of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations.

The bust was previously identified as a portrayal of the emperor Trajan, but recent epigraphic research conducted by Prof. Dr. Stephen Mitchell had made it possible to link one of the portraits mentioned in the second decree of the Artists’ association to one of the benefactors of the mystikos agon. Accordingly, Prof. Dr. Stephen Mitchell identify the round tondo bust as a portrait either of Ulpius Aelius Pompeianus, or of an anonymous benefactor of about the same period.

The statue of Hadrian from Ancyra is one of six cuirassed statues of the emperor that have been found across Anatolia. Two come from Perge, one from Troy, another one comes from Tlos and finally one headless statue comes from Aphrodisias.

My Hadrian1900 project will bring me back to Ankara in October 2017. I will be following the Ancyra – Nicea route that Hadrian took on his way to Rome as the new Emperor (the so-called Pilgrim’s Road connecting Byzantium to Antiochia). It will be the occasion to write more about Hadrian’s connections with Ancyra.

Sources & references:

- Evers, Cécile. 1994. Les portraits d’Hadrien typologie et ateliers. Bruxelles: Académie royale de Belgique.

- Candemir Zoroğlu. 2014. The Cuirassed Statue of Hadrian at Ankyra Theatre. Ankara University, Journal of the Archaeology Department.

- Stephen Mitchell. 2014. The Trajanic Tondo from Roman Ankara: In Search of the Identity of a Roman Masterpiece. Ankara Araştırmaları Dergisi – Journal of Ankara Studies. (read pdf here)

- Mary T. Boatwright. 2000. Hadrian and the Cities of the Roman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. 101

- Mitchell, S., French, D. 2012: The Greek and Latin Inscriptions of Ankara (Ancyra) Vol. 1: From Augustus to the end of the third century AD. Munich

- Epigraphic database for ancient Asia Minor http://www.epigraphik.uni-hamburg.de/database