Today we have another contribution from Timeless Travels Magazine in which Dr Christine Winzor writes about the colossal stone heads at Nemrut Dağ, Turkey.

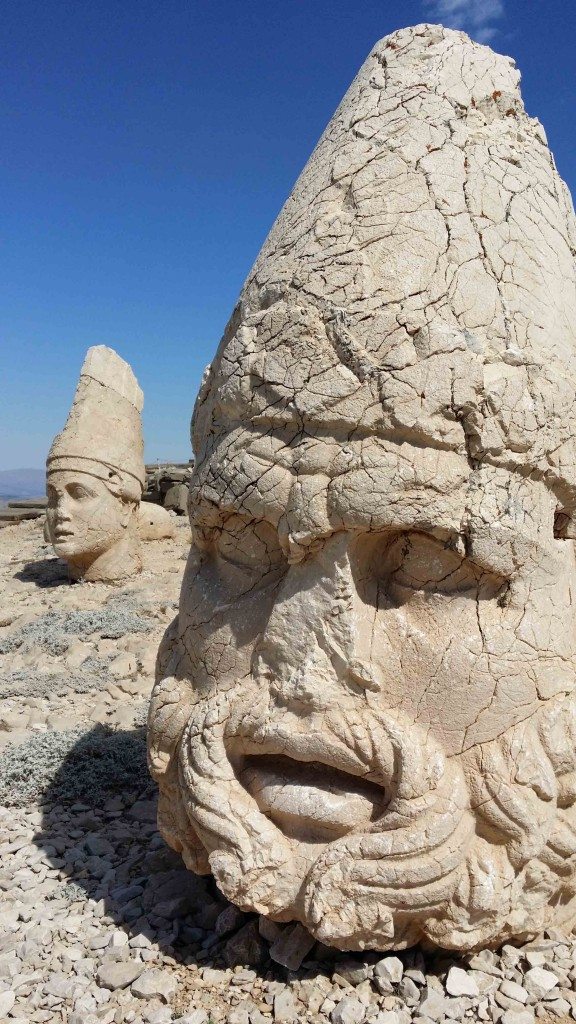

The colossal stone heads at Nemrut Dağ, with their distinctive array of crowns and caps, are among the most iconic images of Turkey. Many guidebooks and tour agencies stress the importance of visiting this monument – sometimes referred to as the Throne of the Gods – at either sunrise or sunset to appreciate fully the spectacular illumination and reflection of the sun’s rays on the sculptures and tumulus. Others specifically advise against visiting at these times on the grounds that inevitably you will share this impressive event with a large crowd of other spectators, thereby spoiling the sense of majestic isolation.

Nemrut Dağı is one of Turkey’s most famous sites, with its colossal stone heads perched on top of a mountain, but few know of its history or function. Christine Winzor visited when the snow was thick on the ground.

However, as art historian and travel writer Francis Russell sapiently notes, ‘Nemrut Dağı is extraordinary at any time of the day or season of the year. But to see the great heads emerging from the winter’s snow is an unforgettable experience.’ And early April, the beginning of Spring, was precisely when I first saw the giant heads peeping out from the snow.

As recently as forty years ago travelling to Nemrut Dağı, one of the highest peaks of the Eastern Taurus mountain range in south-eastern Turkey, was an arduous journey, involving many hours of walking or riding mules through the desolate, mountainous countryside. While still an adventure beyond the comfort zones of Istanbul and the well-known Turkish coastal resorts, for today’s visitor the trip is relatively simple, as the site, located within the Nemrut Dağı National Park, can be reached by good roads either from Adıyaman via Kahta (approximately 75 km along the D360) or from Malatya (approximately 120 km along the D300). Both cities are served by daily domestic flights from both Istanbul and Ankara. A steep, but paved road leads to a car park at the base of the summit, from which it is a 600 metre steady climb along a well-trodden path to the sanctuary. Visitors are well advised to dress warmly for this final ascent, for at any time of year it can be bitterly cold and windy at the summit.

Crowned by the 50 metre high tumulus of crushed limestone rocks, Nemrut Dağı, at 2,150 metres above sea level, is prominent and visible in every direction, but it was only in 1881 that a German engineer, Karl Sester, reported the discovery of a large number of colossal statues, which he believed to be Assyrian in origin. The following year, he returned with Otto Puchstein, from the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin, to investigate the site further, and from an examination of the iconography of the sculptures, it was evident to Puchstein that the figures were not Assyrian. A lengthy inscription in Greek, reading ‘The Great King Antiochus, the God, the Righteous One, the Manifest, the friend of Romans and Greeks, the Son of Mithradates Kallinkos and of Laodice, the brother-loving Goddess, the daughter of King Antiochus Epiphanes, the mother-loving, the Victorious, has recorded for all time, on consecrated pedestals with inviolable texts the deeds of his clemency,’ enabled the attribution of the monument to Antiochus I, the Hellenized ruler of Commagene, one of the many small kingdoms to emerge in Anatolia as a result of the fragmentation of the Seleucid Empire.

Antiochus I and the Kingdom of Commagene

Citing the official line proffered by the local Chamber of Commerce, our enthusiastic young Kurdish guide proudly told us that the term Commagene is derived from a Greek word meaning “community of genes”. Scholars, however, explain the name as a derivative of the 8th century BCE Neo-Hittite Kummuh (or Kummuha) found in Assyrian sources, referring originally to the main city of the region, and subsequently assigned to a wider region of fertile land between the Anti-Taurus Mountains and the Euphrates River in south-eastern Turkey. The independent Neo-Hittite principality of Kummuh was destroyed by the Assyrians at the end of the 8th century BCE, and later became part of the coastal satrapy of Syria after the conquests of the Achaemenid Persian king, Darius the Great (521-586 BCE). After the Battle of Issus in 333 BCE, the region was engulfed by Alexander the Great’s growing empire and the name Kummuh was Hellenized to Commagene.

Upon Alexander’s premature death in Babylon in 323 BCE, his vast empire, which stretched from Greece and Macedonia in the west to India and Afghanistan in the east, was carved up among his generals. These successors established their own kingdoms, and Commagene fell within the largest of these, the territory ruled by the Seleucid dynasty, named after its founder, Seleucus I Nicator. By the 2nd century BCE, internal disputes and civil war weakened the hold of the Seleucids over much of Asia Minor and various local rulers seceded, founding their own kingdoms.

Commagene became an independent political entity in about 163/2 BCE under Ptolemaios, a local satrap, who claimed a complicated lineage from both the Orontid Armenian and the Iranian Achaemenid dynasties. He was succeeded by his son Samos, who founded the new capital city and fortress of Samosata on the west bank of the Euphrates (now submerged by the Atatürk Dam). Samos exploited Commagene’s geographical position as a buffer state and formed carefully calculated alliances with both the neighbouring Seleucids and the Parthians. To ensure peace between the kingdom of Commagene and the Seleucid empire, Samos’s son, Mithradates I Kallinkos was married to the Seleucid princess, Laodice Thea Philadelphus, daughter of Antiochus VIII Grypus. However, during the civil war between Antiochus VIII Grypus and his half-brother, Mithradates broke away from the Seleucids and Commagene was officially declared an independent kingdom in 80 BCE.

As the Greek inscription cited above attests, Antiochus I, the builder of the monument at Nemrut Daği, was the son of this illustrious union between Mithradates and Laodice and the most influential king of the dynasty. Forced by Pompey into an alliance with Rome, Antiochus I expanded his realm and gained control of the strategically important crossing of the Euphrates River at Zeugma. Despite styling himself as a friend of the Romans (philoromaios), Antiochus’ Iranian descent nevertheless led him to gravitate towards the Parthians and he married his daughter, another Laodice, to the Parthian king Orodes.

Ultimately, the Parthian allegiance led to the kingdom’s downfall, with the Commagene dynasty ending in 72 CE when the Roman Emperor Vespasian deposed Antiochus IV for his alleged intrigue with the Parthians against the Romans. The region was then transformed into a Roman province as part of North Syria and the name Euphratensis was substituted for Commagene.

Marginalized and neglected by historians, Orientalists and Classical scholars, the Commagene Kingdom, Antiochus and his magnificent monument on the summit of Nemrut Dağ remained forgotten for centuries until its rediscovery and subsequent exploration by Karl Sester and Otto Puchstein. Puchstein returned for a second expedition with Carl Humann (discoverer of the Great Altar at Pergamon) in 1883, and in the same year, the Ottoman government sent the director of the Imperial Museum in Constantinople, Osman Hamdi Bey, and the sculptor Osgan Efendi to Nemrut Dağı to study the monument and its inscriptions.

Further investigations were not conducted at Nemrut Dağı until seventy years later, when Theresa Goell, under the auspices of the American School of Oriental Studies (ASOR), conducted systematic excavations from 1953 to 1973. The 2005 film, Queen of the Mountain, documents her struggles and the obstacles she overcame to devote herself to an archaeological career and the excavation of Nemrut Dağı. After Goell’s death, work to locate the actual burial chamber under the tumulus using ground radar and magnetic measurements was continued by her German collaborator, Friedrich Karl Dörner. Subsequently, work at the site continued in the 1980s under the direction of Professor Dr Sencer Şahin. In 1988 Nemrut Daği was declared a national park and added to UNESCO’s official list of world heritage monuments. Currently, international operations are focused on preserving the monument from the harsh natural elements.

Inscriptions identify the monument at Nemrut Dağı as a hierothesion, or tomb-sanctuary, a rare term which appears to have been coined by Antiochus I himself to describe the sanctuaries he built at the sites of royal burials. At Nemrut Dağ Antiochus established a highly sophisticated royal cult for the worship of himself as the deified ruler, of his royal ancestors and of a pantheon of carefully chosen syncretic gods, who combine Greek and Persian elements. This awe-inspiring funerary monument, which comprises a tumulus, three terraces and an altar, is a testimony to the aspirations of Antiochus – to be buried close to the celestial throne and to leave a lasting legacy of his descent from both Alexander the Great (through his Seleucid mother) and the Achaemenids of Persia.

East & North terraces

This article was originally published in Timeless Travels magazine. Republished with permission.

From the car park, the visitor climbs the pathway up along the southern side of the tumulus directly to the East Terrace. Care is needed if the path is covered in snow, as there is a steep drop to the side and strong wind conditions can add to the discomfort and difficulty of the climb. At the top, an open sanctuary area of about 500 square metres is reached, bordered on its eastern perimeter by

a stepped fire altar recalling Zoroastrian traditions. On clear days the view from this terrace across the surrounding countryside is absolutely breathtaking, and provided the ground is not covered

by snow, the visitor can discern the route of the processional way winding its way up to the sanctuary.

With their backs to the tumulus, a row of five colossal seated figures, set on a tiered podium about seven metres above the sanctuary level, face towards the sunrise. Built in courses of ashlar blocks, originally each statue would have stood between eight and nine metres high, and they bring to mind the Colossi of Memnon at Thebes. Their heads, which alone measure two or more metres in

height, have tumbled to the sanctuary floor as a result of seismic activity in the region, and have now been carefully arranged in a line in front of the appropriate statue. These seated figures are flanked on either side by statues of a lion and an eagle, intended to protect the sanctuary. A chain fence and a whistle-blowing guard prevent close access to the sculptures, but the visitor cannot help being overwhelmed by the majesty and scale of these figures.

From the lengthy thanksgiving inscription carved into the rear of their thrones and their distinctive iconography, these five enthroned figures have been identified as Antiochus and a pantheon of Graeco-Persian tutelary gods. In the centre, in accordance with the hierarchy of the deities, is Zeus Ahuramazda, the “lord of knowledge” in Zoroastrianism, the largest statue. He wears a cloak over his long-sleeved tunic, an apron-like skirt and low boots and holds a bundle of twigs (barsom) symbolizing the sacred fire used during Persian-Mithraic religious rituals. His head is crowned with a Persian tiara and his face is fully bearded. The winged thunderbolt relief on Zeus’ diadem distinguishes it from the diadems of the other deities.

As one faces the colossi, the statue of Tyche, or Fortuna, the goddess of Commagene, is seated to the left (south) of Zeus. She is the only female figure among the deities and up until the 1960s, this statue was still intact, with her head on her shoulders. The goddess wears a himation and high sandals and is holding a cornucopia filled with fruit and flowers in her left hand. She also has a garland of fruit in her right hand and lap. A basket made from a separate block of stone was originally fitted into a round socket on the goddess’s head.

Apollo-Mithras-Helios-Hermes is seated to the right of Zeus, and this syncretic deity represents the fusion of the Greek god of the sun with the Persian Mithras, god of light and the helper of Ahuramazda. Like Zeus, he wears a cloak over a long-sleeved tunic, an apron-like skirt, and low boots, and holds a barsom in his left hand, but he is clean shaven.

The god-king Antiochus is seated to the left of Tyche. He wears Persian-style boots and holds a barsom in his left hand like Zeus and Apollo. His face is smooth and clean shaven in the Hellenistic manner, but his head is adorned with a Parthian-inspired diadem and tiara.

Artagnes-Heracles-Ares is seated to the right of Apollo-Mithras. He is dressed like the other gods but holds a club in his left hand. He is bearded like Zeus, but his diadem and tiara are carved out of the same block as his bust.

Carved into the back of these enthroned gods – and hence not visible to the visitor – is the two hundred and thirty-seven line Greek inscription which explains the ruler cult of Antiochus and specifies how the associated rituals should be performed. In a verbose, pompous style, the sacred laws (or nomos) dictate such details as what type of clothes the priests should wear and what utensils the worshippers should eat from.

Goells excavations of the East Terrace discovered a row of five very fragmentary reliefs running below and parallel to the seated gods. Four of these stelae depicted Antiochus greeting the gods – the dexiosis – and the fifth reproduced the so-called horoscope lion relief found earlier by Humann and Puchstein, the significance of which will be discussed in further detail below.

A row of now badly damaged stelae once lined the north and south sides of this sanctuary. On the south side these traced Antiochus’ Greek ancestry on his Seleucid mother’s side to Alexander the Great and on the north side his Persian ancestry via his father Mithradates to Darius. The row of pedestals that once held these stelae is still visible and originally there was a small fire altar in front of each pedestal.

From the East Terrace, the visitor follows the processional way around to the long, narrow North Terrace bordered by a series of sandstone pedestals. The stelae lying nearby are all unworked, bearing no inscriptions or reliefs, possibly indicating that they were left unfinished at the time of Antiochus’ death in about 36 BCE. In early spring, this northern side of the monument may still be covered in snow, which at the time of my first visit in early April reached thigh-high. The pathway was deeply buried and it took considerable effort to battle through the deep snow to the West Terrace. The less adventurous members in our group turned back to the car park along the path on the southern side of the tumulus.

The cone-shaped tumulus itself is made up of 30,000 cubic metres of crushed limestone rubble and is 50 metres high and 150 metres in diameter. Despite repeated attempts, neither excavation nor tunnelling nor modern resistivity or seismic refraction methods have located any sign of a burial chamber. To the disappointment of archaeologists and visitors alike, Antiochus’ tomb remains successfully concealed beneath the man-made mound, which represents a significant engineering feat. From the lack of votive offerings by worshippers at the sanctuary, it is generally assumed that the site was abandoned almost immediately after Antiochus’ death in about 36 BCE. As Oxford Professor Bert Smith writes, “It can be reasonably suspected that the cost was disproportionate and the religious response was minimal”.

The West Terrace

The West Terrace is considerably narrower than its eastern counterpart, and had no main altar. With their backs once again to the tumulus, but facing the setting sun, the sequence of giant enthroned gods and their guardian lions and eagles is repeated on the West Terrace. However, those on the West Terrace are in a more ruinous condition, standing only two or three courses high and lack the commanding dominance of their counterparts on the East Terrace. But their colossal toppled heads are better preserved, and when not buried tantalizingly in snow, it is easier to observe the carved detailing of their head gear and hairstyles.

The genealogical reliefs depicting Antiochus’ ancestors are also duplicated, but due to the limited space on this smaller terrace they are arranged at right angles to each other, with the plinths of the shorter Persian series forming the southern perimeter of the sanctuary, while the longer set of Greek forebears lines the western edge, and faces the seated deities. Originally arranged in line at a slightly lower level at the northern end of the row of enthroned gods and flanked at each end by a small lion and eagle were another series of dexiosis stelae depicting Antiochus shaking hands with each member of his pantheon.

The celebrated lion horoscope relief, mentioned above, found by Puchstein and Humann in 1883, also belongs to this sequence. The relief depicts a lion with a magnificent full mane and a crescent moon slung below his neck against a low relief pattern of nineteen stars representing the constellation Leo. The three largest stars are identified by inscriptions as Jupiter, Mercury and Mars, and the brightest star on the lion’s neck is the basilisk, or royal star of Antiochus, while the crescent moon is the symbol of the national goddess of Commagene. The conjunction of the celestial planets has been variously calculated to represent a date in July of 61 or 62 BC, but scholars are uncertain as to the exact significance of this date. Some have proposed that this may be the shrine’s foundation date or Antiochus’ birthday; others that it represents the date a political agreement between Antiochus and Pompey was reached.

Due to their very fragile state of preservation and the very harsh weather conditions prevailing on the mountain side – UNESCO identifies environmental factors such as serious seasonal and daily temperature variations, freezing and thawing cycles, wind, snow accumulation, and sun exposure as threats to the monument – some of these reliefs have already been removed and replaced with barely distinguishable replicas. Concerned about the damage, a few years ago the then Turkish Minister for Culture and Tourism proposed removing the giant heads from the mountainside by helicopter and establishing a museum to display them, but this radical plan has not been implemented and archaeologists and scientists are working together to conserve these unique sculptures.

Visitors capable of making the descent in the twilight can wait on the West Terrace until sunset before returning to the car park for a very welcome glass of Turkish çay at the Resthouse. But for travellers whose interest in the Commagene Kingdom has been aroused and with a bit more time on their hands there are another two significant sites in the vicinity which are well worth the detour.

Arsameia & Karakuş

Approximately fifteen kilometres from Nemrut Dağ, along the road to Adıyaman via Kahta, and situated above the modern village of Kocahisar (formerly Eski Kahta) are the remains of Arsameia on the Nymphaios, where Antiochus built a hierothesion for his father, Mithradates I Kallinkos. Excavated by Friedrich Karl Dörner in the 1950s, the site consists of a processional way which zigzags its way up the hill to the entrance of a deep tunnel, extending about 160 metres into the mountainside. Above the tunnel entrance is a 250 line Greek text in five columns, which describes the building activities of Antiochus at Arsameia and specifies the ritual celebrations to be practised in honour of his father.

Fragmentary remains of a line of colossal statues have been discovered on the hilltop in front of the traces of a free-standing altar, but for the visitor to Arsameia, the most striking features are the remaining relief sculptures which line the processional way. The first stele encountered by the visitor stands five metres high and depicts Apollo-Mithras and originally formed part of a dexiosos scene, with the god shaking hands with the Commagene king. A second, less well-preserved pair of stelae further up the processional way depict Antiochus and his father Mithradates. Best of all, located above the tunnel entrance is a magnificent monumental relief, almost three and a half metres high, which scholars consider the finest surviving piece of Commagene sculpture. Almost perfectly preserved, the relief shows a naked Atagnes-Herakles-Ares, with his distinctive lion skin slung over his shoulders and holding his club in his left hand while shaking hands with Antiochus. The Commagene king is splendidly attired in Persian dress of tunic and robe and wears an Armenian kitaris – a high pointed cap and tiara – on his head. The image the visitor takes away with them is of a Commagene ruler who felt at ease in the company of the gods.

Continuing about six kilometres along the road to Adıyaman, the traveller passes the incredibly well-preserved Roman bridge at Cendere which was built by the Roman legion XVI Flavia Firma in about 200 CE. Then after another ten kilometres a commanding man-made tumulus is reached. Thirty metres high and with a diameter of 150 metres, this conical tumulus is another royal Commagene burial site. Colloquially known as Karakuş (black bird) after the statue of an eagle mounted upon one of the remaining standing columns, this funerary monument was built by Antiochus’ son, Mithradates II for his mother, Isias, his sister Antiochis and his niece, Aka. Another sister, Laodice, who was married to the Parthian ruler, Orodes II, is also honoured in an inscription found on a dexiosos relief depicting the siblings. The tumulus is built of gravel and sand and the collapsed south-western slope is evidence of the activity of tomb robbers in antiquity. When Dörner excavated the interior of the mound in 1967 he found the burial chamber empty.

Quite fittingly, the peak of Nemrut Dağı, the final resting place of Antiochus I, the husband, father and grandfather of the Commagene women buried at Karakuş, is clearly visible to the north, as though with his divine companions this vainglorious king, who assumed the epithet Theos (God), was keeping watch over his female relatives.

References:

- Başgelen, Nezih, 1998, Nemrut: Mountain of the Gods, trans. by Fatma Artunkal & Neşe Olcaytu, Istanbul, Archaeology & Art Publications.

- Blömer, Michael & Winter, Engelbert, 2011, Commagene: an archaeological guide, Istanbul, Homer Kitabevi.

- Russell, Francis 2010, Places in Turkey: a pocket grand tour, London, Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd.

- Sanders, Donald H. (ed.), 1996, Nemrud Daği: the Hierothesion of Antiochus I of Commagene, vols 1 & 2, Winona Lake, Indiana, Eisenbrauns.

- Sagona, Antonio, 2006, The Heritage of Eastern Turkey from earliest Settlements to Islam, Melbourne, Macmillan.

- Smith, R.R.R., 2012, Gods of Nemrud: the Royal Sanctuary of Antiochos I and the Kingdom of Commagene, Istanbul, Ertuğ & Kocabiyik.

About the Author

Dr Christine Winzor is an archaeologist, teacher and librarian, with an Honours degree in Archaeology from the University of Sydney, and a D.Phil. in Classical Archaeology from Oxford University. She has taken part in excavations at Pella in Jordan and at Torone in northern Greece and has conducted fieldwork in Greece, Turkey and Egypt. Christine has lived and travelled extensively in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean for the last twenty-five years, and her special interests include Hellenistic architecture, the Roman East and the development of the Ruler Cult.