Two thousand years ago, Mount Vesuvius – a stratovolcano located close to the Gulf of Naples – erupted with tremendous force and little warning. Within only 24 hours, the Roman city of Pompeii was buried under a rain of hot ash and falling debris. Lying undiscovered for over 1,600 years, the city’s rediscovery remains one of the greatest archaeological finds of all time.

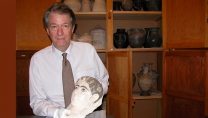

Pompeii: In the Shadow of the Volcano, which opened last month at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, Canada, examines everyday life in Pompeii through six distinct sections on those who called the ancient city home. (The exhibition then travels to the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts in February 2016.) In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Curator Paul Denis about the exhibition as well as the ways in which our lives mirror those from the distant past.

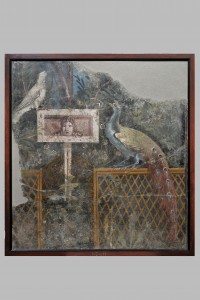

Garden Fresco. Painted plaster. MANN 8760. ©The Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage of Naples (SAHN).

JW: Paul Denis, thank you so much for speaking with me about Pompeii: In the Shadow of the Volcano. It was a pleasure to see the exhibition and meet you in person.

I know that ancient Greek sculpture is a specific interest of yours, so how did you feel about organizing an exhibition on what is perhaps the most iconic Roman city?

PD: It was a “once in a life time” experience, James. I recently completed the ROM’s permanent Etruscan and Roman galleries and so working on the Pompeii exhibition was an easy transition. Also, it was a great pleasure working with my Italian colleagues in Naples and Pompeii. They were very helpful and extremely generous with their loans.

JW: Paul, what obstacles did you and your colleagues at the ROM face in organizing Pompeii? How did these challenges compare with the previous exhibitions you’ve organized over the years?

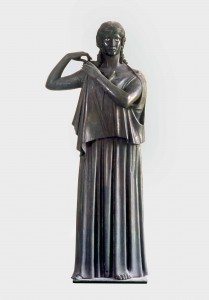

Woman fastening her peplos (Peplophoros). Bronze. Found in the Villa dei Papyri, Herculaneum. MANN 5619. ©The Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage of Naples (SAHN).

PD: There were two main obstacles we faced. The first was trying to fit 200 objects into the space of the Garfield Weston Exhibition Hall. Not just “fit” but also to properly design the displays with accompanying story lines. Our exhibit design team skillfully met the challenge and did an outstanding job. Secondly, we were tasked to write shorter and simpler label texts. Previous exhibitions included much higher word counts. As a result, the Pompeii labels are simple, easy to read, and very informative. The shorter a label, the harder it is to write!

JW: I had previously thought that Pompeii was akin to a Roman version of Las Vegas; a city devoted to the pleasures of visitors and the patrician elite. However, this exhibition reminds us that Pompeii was a prosperous Roman city linked to Rome’s robust trading network. In essence, it was your typical Roman town.

Might you elaborate and tell us how Pompeii underscores this point?

PD: Pompeii was an entertainment center for the region. For example, the amphitheater, where the gladiatorial games took place could seat 20,000 people but the population of Pompeii was about 12,000. So people flocked to the city for the games and other entertainments. At the same time, Pompeii was your typical Roman town with a thriving market place, streets bustling with activity, a city government, a court house, temples for the worship of their gods, and an infrastructure that included supplying clean water to everyone. The exhibition imparts the vitality and dynamism of urban life.

Gladiator Helmet. Bronze. With permission of the Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage of Naples (SAHN). MANN 5671. ©ROM 2015.

Even though Pompeians did not have computers and iPhones, one learns how similar life in Pompeii was to the present-day. They enjoyed the same types of entertainment, “fast food restaurants,” and lively bars. The pots and pans they used for cooking look amazingly close to ours. The top one per cent of Pompeian society not only loved their wealth, but they enjoyed flaunting it.

JW: The people of Pompeii form the heart of the exhibition, and it was difficult not to be moved by the objects on display. I was drawn to the items of everyday life: a gladiator’s helmet; oil lamps; coins and scales used by men of commerce; a pitcher which once held garum; and even food that had been preserved for over two thousand years.

Of the objects shown at the exhibition, which resonate with you the most and why? Would you say the exhibition has any “star” attractions?

PD: I would say that the exhibition has many “star attractions.” From an artistic point of view, the marble statue of the goddess Isis is one of the top artifacts. She is so beautifully carved with an elegant, soft face and fine drapery covering her body. The exquisitely crafted silver wine drinking vessels and the silver dining ware are other favorites of mine.

Mirror Decorated with Cupids. Silver. MANN 12607. ©The Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage of Naples (SAHN).

JW: While at the exhibition, I spoke to Dr. Sascha Priewe, who also helped organize Pompeii, and he mentioned that Vesuvius might not have erupted in the late summer of 79 CE. Indeed, some scholars contend that the volcano erupted in the fall.

I hadn’t heard this beforehand. Don’t we have a precise timeline of events, concerning Vesuvius’ eruption, from Pliny the Younger (61-112 CE)?

PD: According to Pliny the Younger, Vesuvius erupted in the early afternoon of August 24, 79 CE. More recently, scholars believe that the volcano erupted several months later in the autumn of 79 CE. Apparently, some of the produce found in Pompeii, including the pomegranate, is not harvested until the early fall. Furthermore, a lot of braziers, containing charcoal, were found in the rooms of many houses. Braziers were like portable room heaters in ancient times. It has been suggested that rooms would not need to be heated in August but in a cooler autumn.

JW: Let’s remember that Vesuvius is still an active volcano, threatening the metropolitan region of Naples, which includes over three million inhabitants.

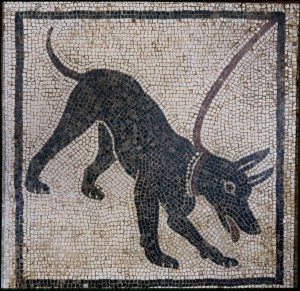

Mosaic of a guard dog. Limestone. MANN 11066. ©The Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage

of Naples (SAHN).

What lessons does the exhibition impart to those who come and visit? Would you say that Pompeii emphasizes ancient history’s relevance to the present-day?

PD: Even though Pompeians did not have computers and iPhones, one learns how similar life in Pompeii was to the present-day. They enjoyed the same types of entertainment, “fast food restaurants,” and lively bars. The pots and pans they used for cooking look amazingly close to ours. The top one per cent of Pompeian society not only loved their wealth, but they enjoyed flaunting it. Politicians running for office handed out free bread to garner votes, much like today’s politicians, who hand out different types of free bread! The list goes on….But most of all, what we can learn from Pompeii is the fragility of life. One day Pompeii was a vibrant city filled with life and in less than a day, life vanished completely.

Earrings. Gold set with amethysts. MANN 109562. ©The Superintendence for the Archaeological Heritage

of Naples (SAHN).

JW: Paul Denis, I thank you again for speaking with me about this exhibition. We eagerly await the ROM’s next undertaking. I, for one, cannot wait to return to Toronto!

PD: James, the pleasure is mine. Thank you for visiting the ROM and the exhibition. I’m so glad you enjoyed it!

Pompeii: In the Shadow of the Volcano is on display at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada until January 3, 2016. Thereafter, it will move to the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts from February 7 – September 5, 2016. This exhibition is organized in partnership by the Royal Ontario Museum and the Montréal Museum of Fine Arts, in collaboration with the Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage of Naples (SAHN) and the Soprintendenza Speciale per Pompei, Ercolano e Stabia (SSPES).

Curator Paul Denis has worked at the Royal Ontario Museum in the Greek and Roman section since 1981. Originally interested in Greek sculpture, during the last 20 years he has broadened his scope to include most aspects of Greek, Etruscan, Roman and Byzantine art and culture. Generally, his work focuses on the associated research and preparation of objects for permanent galleries and temporary exhibitions; the acquisition of artifacts for the collections; and fundraising for galleries, exhibitions and acquisitions. Paul was the lead curator responsible for the development of the following permanent galleries: The A.G Leventis Gallery of Ancient Cyprus; Bronze Age Aegean and Geometric Greece Gallery (all 2005); the Eaton Gallery of Rome, the Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of the Eastern Roman Empire, and the Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Gallery of Byzantium (all 2011). These galleries highlight pieces from Canada’s most important collection of Greek, Etruscan, Roman, and Byzantine art. Collections of particular merit are: vases, marble sculpture and terracotta figurines; Roman marble portraits; and Byzantine decorative arts and mosaics. Paul also curated such exhibitions as, Gift of the Gods: The Art of Wine Revelry (2001) and more recently Fakes and Forgeries: Past and Present (2010), an exhibition that examines the art of fakery, from works of art to fossils, and from counterfeit batteries to knockoff Dior purses. Paul’s current research is focused on Pompeii. He is also researching the depiction of a wedding scene preserved on a fragmentary red-figure lebes gamikos (wedding vase) in the ROM’s Diniacopoulous Collection. The vase dates to about 425 BC and is attributed to the Washing Painter, an Attic vase painter who specialized in nuptial scenes. Another area of research is a recently acquired marble statuette of a late Archaic Greek Kore (Greek for maiden) dating to about 500-490 BCE.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Royal Ontario Museum have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Ms. Marilynne Friedman, Senior Publicist at the Royal Ontario Museum, for helping facilitate this interview. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.