Once a thriving port city on the island of Cyprus, the legendary birthplace of Aphrodite, Salamis offers a tantalizing glimpse into the vast history of the island. The ruins of the ancient city occupy an extensive area (one square mile) extending along the sea shore against the backdrop of sand dunes and a forest of acacias.

According to ancient Greek tradition, Salamis was founded after the Trojan War by the archer Teukros, son of King Telamon, who came from the island of Salamis. Half-brother to the hero Ajax, Teukros was unable to return home from the war after failing to prevent his half-brother’ suicide, leading him to flee to Cyprus where he founded Salamis. After its legendary beginnings, Salamis later became one of the most important cities on the island and the seat of a powerful kingdom. Archaeologists believe that Salamis was first established by newcomers from the nearby site of Enkomi following the earthquake of 1075 BC. The city was subsequently controlled by the Persians until the arrival of Alexander the Great into Asia Minor. Following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC Salamis came under the control of the Ptolemaic dynasty until its incorporation into the Roman Empire in 58 BC. The importance of the city is reflected in archaeological findings dating back to the Late Geometric periods (8th century BC) to Byzantine times (6th century AD).

Salamis was affected by destructive earthquakes. The earthquake of 76-77 AD was among the most destructive, with a magnitude between 9 and 10. Salamis took the brunt of this earthquake, and fell into ruin. The Jewish insurrection of Artemion in 116 AD further devastated the city. Salamis was rebuilt by the emperors Trajan and Hadrian who embellished it with lavish public buildings.

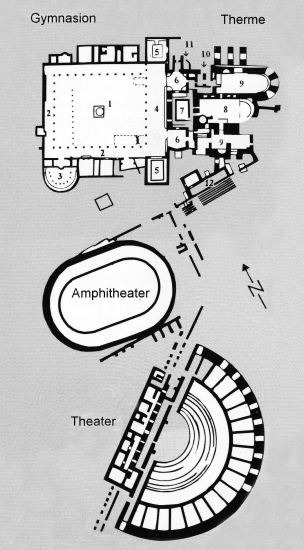

The site has been excavated intermittently from the 1880’s until 1974 and large areas have been opened up. The most impressive monuments of the city date to the Roman period, such as the Theatre (see images here), the Temple of Zeus (Teukros established the cult of Zeus Salaminios at Salamis), the Baths. But the ancient town’s most striking feature is the gymnasium where the young citizens would exercise their bodies and minds. Its remains, with colonnaded courtyard and adjacent pools, allude to Salamis’ glory days.

The Ruins of Salamis

The vast exercise ground was discovered in 1882 and finally excavated in 1952 when the marble columns were re-erected. The Gymnasium was originally laid down during the Hellenistic period, as testified by epigraphic and archaeological evidence, but it was destroyed by an earthquake and rebuilt during the reign of Augustus. The Gymnasium was destroyed once again under the reign of Vespasian following the earthquake of 76 AD. It was restored by Trajan and Hadrian after the Jewish insurrection of 116 AD with a roofed colonnade along all four sides and bathing facilities. An inscription embedded in the pavement dating from the Early Christian period refers to the construction by Trajan of the roof of a swimming pool of the Gymnasium. Hadrian also contributed to the embellishment of the building, and several honorific decrees have been found which mention him as a “benefactor and saviour of the city”.

In the 4th century AD two more earthquakes struck the area. The building was partly restored by the Byzantine emperor Constantius II who remained the city Constantia. The marble columns crowned by Corinthian capitals of various types were taken from the stage building of the nearby theatre as well as other buildings. They replaced the stone pillars of the Roman gymnasium. This explains the mismatching of some of the columns and bases and why they differ in size. The visible remains date from these two late restorations.

During the Hellenistic period, the palaestra had a small circular pool in its centre while during the reign of Augustus a statue of the Emperor stood there.

Two marble pools occupied the two ends of the eastern colonnade of the Gymnasium. The pools originally had a small roofed portico and were surrounded by nude statues of the gymnasiarchs but these were later smashed by Christians. They have now been replaced by a collection of headless statues found at the site. They were probably defaced by Christians zealots who considered them as symbols of pagan idolatry.

At the south-west corner of the palaestra lie the gymnasium’s latrines, a semicircular colonnaded structure in which there was seating was 44 people. They are the largest ever found in Cyprus.

Salamis Statues in the Cyprus Museum

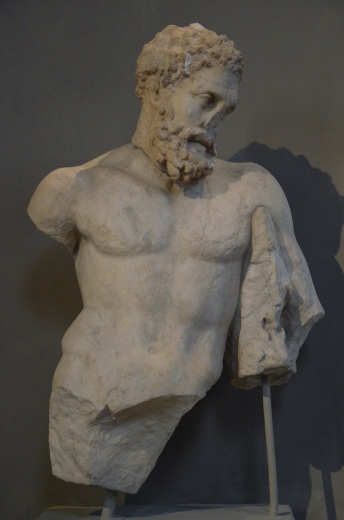

During excavations, several marble statues were discovered which adorned the spacious stoas of the Gymnasium. Many that had survived numerous raids have disappeared since 1974. Fortunately, some made it to Nicosias’ Cyprus Museum and are now prized exhibits.

The statues date from the Hadrianic period and are all of remarkably good quality. Sadly, few statues were found with their heads on and among these are two over life-size statue of Hera and of Apollo Citharoedus (the lyre-player).

Some of the statues, such as those of Asklepios and Nemesis, were re-used, while others that were reminiscent of the ancient pagan worship, such as Isis, Zeus, Apollo and Aphrodite were used as building material or were thrown into pits and water tanks of the Baths of the Gymnasium.

Salamis was destroyed by repeated earthquakes in the middle of the 4th century AD, but was quickly rebuilt as a Christian city by the Byzantine emperor Constantius II who renamed the city Constantia. Salamis was finally abandoned during the Arab invasions of the 7th century after its destruction by Muawiyah I. The inhabitants moved to Arsinoë (modern-day Famagusta).

For anyone interested in ancient history, Salamis is a treasure-trove of ancient Greek, Roman and Byzantine remains where visitors can explore crumbling basilicas, royal tombs and wander along classical colonnades.

Sources and references:

- Vassos Karageorghis, Salamis in Cyprus, Homeric, Hellenistic and Roman (1969)

- Mitford & Nicolaou, The Greek and Latin Inscriptions from Salamis (1974)