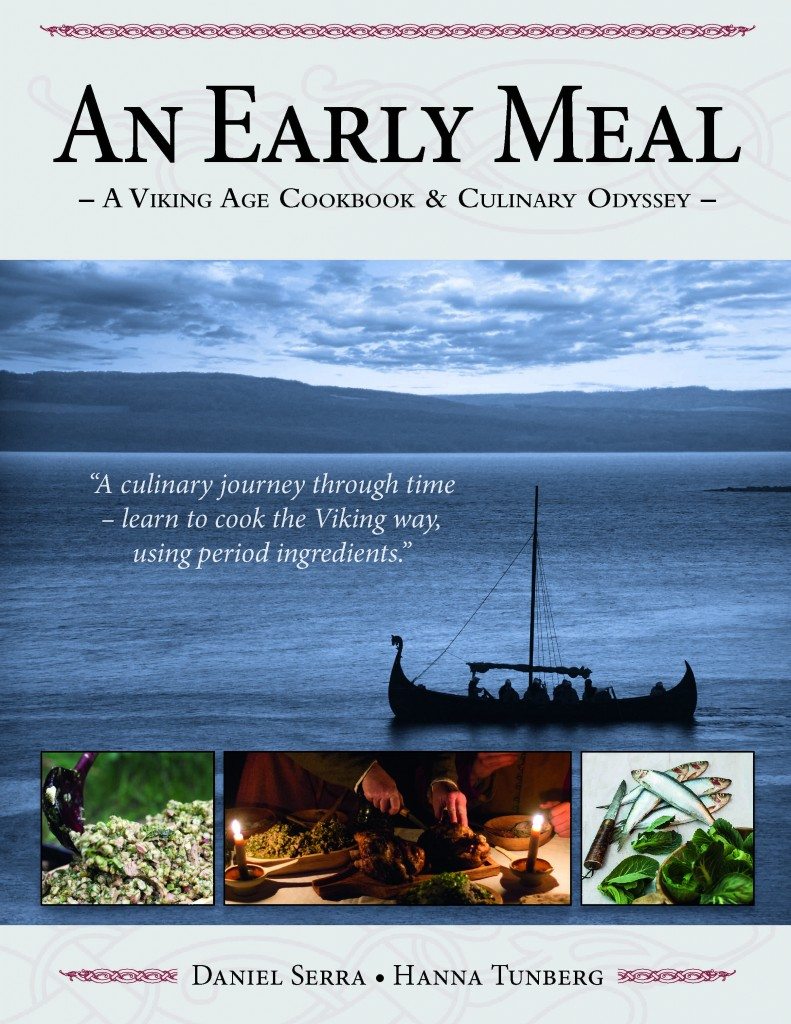

An Early Meal: A Viking Age Cookbook & Culinary Odyssey by Daniel Serra and Hanna Tunberg introduces readers to Viking Age food and cuisine from early medieval Scandinavia. Thoroughly based on archaeological finds, historical cooking methods, and current research, the book is a must-read for those interested in Old Norse culture and food history. Within its pages, the authors dispel many of the prevalent myths that persist about Viking Age food and cookery, share reconstructed recipes, and impart new information drawn from years of experimental research in the field.

In this exclusive 2015 holiday season interview, Daniel Serra discusses Viking Age food and Old Norse culture with James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE).

JW: Mr. Daniel Serra, welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) and thank you for speaking to us to An Early Meal: A Viking Age Cookbook & Culinary Odyssey. (Readers can preview this title and look at some recipes through this excerpt.)

I have read that you are currently writing your doctoral thesis on a similar topic, so you must have a deep-seated curiosity in food history. What stimulated your interests in Viking Age food and culture? If I remember correctly, you have an interest in the ancient Roman recipes of Apicius too.

DS: My interest in historical foods emerged when I started my university studies in classic archaeology. As I have always been interested in good food, I was curious what the food was like in the periods I studied. So starting with the recipes of Apicius and Cato, I tried to reconstruct the food and tastes of the ancient Romans. As I moved into archaeology and medieval archaeology, it was natural to move onto medieval food and the recipes that remain from that era. At this point it was not just a culinary curiosity, but rather a tool to teach or inform people about archaeology. I find that a good way to approach history is through all our senses, and taste is an excellent way to create a better understanding and immersion within a certain era. Together with my co-author, Hanna Tunberg, we started a small medieval catering firm; honestly, we sort of trick people into learning something about the medieval period through the meals we offer.

DS: My interest in historical foods emerged when I started my university studies in classic archaeology. As I have always been interested in good food, I was curious what the food was like in the periods I studied. So starting with the recipes of Apicius and Cato, I tried to reconstruct the food and tastes of the ancient Romans. As I moved into archaeology and medieval archaeology, it was natural to move onto medieval food and the recipes that remain from that era. At this point it was not just a culinary curiosity, but rather a tool to teach or inform people about archaeology. I find that a good way to approach history is through all our senses, and taste is an excellent way to create a better understanding and immersion within a certain era. Together with my co-author, Hanna Tunberg, we started a small medieval catering firm; honestly, we sort of trick people into learning something about the medieval period through the meals we offer.

I used quite a lot of Anglo-Saxon texts. Being contemporary with the period we were investigating, they offer say quite a lot about the practices at the time, even if some of the ingredients referenced have not been found in Scandinavia. Further insights into cooking methods and ways of thinking about food could be found in many medieval recipes…The Icelandic sagas and the Eddas did of course provide a lot of inspiration as well…”

In serving food and talking about it with a wide variety of people, I became fascinated with food as a vehicle of cultural and social expression: The consumption of different foods depending on class or role in society, how food can be used to exclude or include people, and how one can express an identity through food. However, as most of the surviving medieval recipes from that era reflect an “upper class menu,” I felt a bit limited and started to look into ways of to approach what ordinary people ate; I turned back into a more experimental archaeological approach.

Wild leaf herb and cheese stew. This recipe was recreated in Lofoten, Norway. (Photo by Stina Nannesson.)

The same approach was of course possible when it came to Viking Age food because this an era where most scholars had looked at the food from a very economic point of view. In parallel with my more theoretical studies, I also tried to recreate tastes and dishes for the purposes of experimental archaeology as well as for Viking Age and medieval reenactment groups too.

JW: What do you believe is the biggest misconception people have of Viking Age food and drink? I suspect many would be surprised by the seasonal and regional variation of foods and flavors found within An Early Meal.

DS: I would say that meat, mead, mushrooms, and forests cloud the popular imagination. A quite common picture of Viking Age food is that it just consisted of mead and meat more or less. In the popular series Vikings — produced by the History Channel and not so accurate overall — the food scenes often present grilled pieces of meat that the protagonists gorge themselves over. Meat would have been a rather festive food, served with porridge, turnips etc., rather than something that was just served by itself. Even though the archaeological evidence is scarce, some of the Viking sagas seem to indicate that the meals were far more well mannered events than many would believe. There are even descriptions on how people washed their hands before and between meals.

Steamed mussels with fennel and leek. This is a recipe comes from Viking Jorvik, which is the present-day city of York, England. (Photo by Stina Nannesson.)

Mead would certainly have been a festive drink, but the most common drink would most likely have been beer; at the time, there was nothing uniquely “Scandinavian” about mead. People also consumed ale. Mushrooms pop up every now and then, perhaps mainly in the context of being a way to induce the rage of the berserker, but this is a misconception from the eighteenth century CE, which endures to this day. In fact, there is nothing to indicate the consumption of mushrooms, neither in texts nor in archaeological evidence. We also have a very romantic notion of the role and use of forests in different historical eras, and many become quite surprised when I say that only about one percent of the bone remains found come from hunted animals. Actually, when looking to the archaeological material, hunting and foraging in the forests seems to be rather limited. But as you say too James, both seasonal and to some extent flavor variations will go contrary to many erroneous and popular beliefs.

JW: Reconstructing ancient cookery seems particularly challenging, Mr. Serra. Did you follow a specific approach in writing and researching An Early Meal? Additionally, which historical sources or records proved the most useful to you and your co-author, Ms. Hanna Tunberg?

DS: Usually when looking at other periods, like ancient Rome or medieval Europe, one would have a few recipes as a starting point even if those recipes are terse and relatively basic. Earlier, I interpreted a late 13th-century Danish cookbook with Hanna Tunberg, which was published under the title En sås av ringa värde (English: “A Sauce of Little Value”) in which the recipes were just like that. When working with Viking Age food and cuisine, the starting point was instead to approach the subject from an experimental archaeological point of view; in contrast to some earlier interpretations of Viking Age food, the archaeological evidence had first priority, whereas the literary evidence was used mainly as inspiration and support in the final stages of research and preparation.

After establishing the possible ingredients and plausible cooking methods, I prepared some simple dishes in the field using authentic cooking methods in order to get an understanding of the limitations and the possibilities that the cooking methods would afford. I then referenced contemporary continental literature; here, I can strongly recommend Ann Hagens’ book Anglo-Saxon Food and Drink: Production, Processing, Distribution and Consumption and some later medieval sources. In truth, I examined many texts in order to find the “building blocks” of Viking cuisine. Following this, I went back into the Viking Age kitchen in order to try out some of the new ideas in their “proper environment.”

I used quite a lot of Anglo-Saxon texts. Being contemporary with the period we were investigating, they offer say quite a lot about the practices at the time, even if some of the ingredients referenced have not been found in Scandinavia. Further insights into cooking methods and ways of thinking about food could be found in many medieval recipes, especially the Danish manuscript we have worked on earlier. (Hannah and I are currently working on making an English translation of our previous book.) The Icelandic sagas and the Eddas did of course provide a lot of inspiration as well. In a few cases, a phrase can even indicate a taste or a combination, which is something I tried to incorporate into An Early Meal; for example, I did this with the recipes of honeyed roasted heart and kale-porridge with smoked herring.

Flat bread prepared as it once was in Viking Age Birka, which is located in present-day Sweden. (Photo by Lovisa Olsson.)

Finally, my co-author and I surveyed and went through the available ingredients for each region or site, discussing what was plausible for each. We focused on the Lofoten islands and Kaupang in present-day Norway, Lejre in present-day Denmark, Hedeby in present-day Germany, Jorvik in the present-day UK, as well as Uppåkra and Birka in present-day Sweden. I searched the Old Norse materials and Viking sagas for inspiration, which could be connected to a certain context or a special site, while Hanna made sure we did not combine ingredients that were only available at certain times of the year. (We did make a few exceptions with dried or stored ingredients).

JW: For those of us who have very little aptitude within the kitchen, how difficult would you say it is to master the art of “Viking cooking”? Although these recipes seem straightforward, I know that looks can be deceiving.

DS: The recipes in the book are adapted to fit both outdoor historical and modern indoor cooking. However, as most of the dishes require boiling at some point in the cooking process, I would say that the majority of the dishes will provide no major problems to those who wish to try them out. Some are a bit more complex, but in most cases they mainly require some patience and hungry taste buds.

The Old Norse used scallions in many recipes just like other ancient Germanic peoples. (Photo by Hanna Tunberg.)

JW: I was delighted to see that the ingredients found throughout An Early Meal seemed familiar to me as a man with strong ancestral ties to Sweden. Would it be fair to say that contemporary Scandinavian cuisine owes much to the Old Norse peoples, Mr. Serra? If so, can we define some sort of cultural continuity?

DS: Rather than cultural continuity, many of the things we recognize is based on the local flora and fauna in Scandinavia; although traditional dishes use many of the same ingredients, the compositions and techniques can and do vary significantly.

We have deliberately chosen not to use traditional Scandinavian cuisine as a starting point as there is almost an 800-year difference between traditional Scandinavian cuisine and Viking Age food. Several culinary influences entered Scandinavian cuisine and started to transform it from within during the medieval era.

Boar stew — a Viking favorite during times of celebration. This recipe was reconstructed in Lejre, which is located in present-day Denmark. (Photo by Hampus Samuelsson.)

JW: I purposefully arranged our interview to coincide with upcoming seasonal festivities in the Americas and Europe. To conclude our interview, would you mind sharing or recommending a suitable Viking meal for the holiday season?

DS: Interesting question, although I have been thinking in lines of a festive meal; as a result, a meal suitable for the holiday season has not really come into my mind yet, so I am going to dig into this question from a few different angles, using several dishes from the book.

The most obvious answer from a Viking’s perspective would have been beer. Because that is what we do know from the period — namely that they were drinking a great deal during Yule or “Yuletide.” Sadly, in the records we have, the actual dishes are not really mentioned. But considering that it was a partly a religious festivity and also done close to the time of year of the annual slaughter, an interesting festive blot-dinner for an affluent jarl would have been a spit roasted honeyed heart and horse meat stew, accompanied with blood-bread and some sausages on the side. With this I would serve a nice strong beer.

For something I would personally consider a “winter warmer,” regardless of modern traditions or old Norse religious ideas, I would serve a dinner consisting of a goose stew together with the smoked malt bread that we reconstructed for Lejre on the island of Zealand in eastern Denmark. Finally, if I were to put together something that would not be to out of place at a modern holiday table, I would go for sausages and some bread boiled in the stock from boiling the sausage together with the boar stew. For a dessert, although a bit out of season, I would serve up the Oseberg-inspired wheat and apple dish.

A hazelnut treat from for those with an incurable sweet-tooth. This delicious recipe was reconstructed at Hedeby, which is located in present-day Germany. (Photo by Stina Nannesson.)

Most of these meals are quite rich in meat, and in Viking times this would have been part of the festive dinner. Again, Scandinavian peoples would have had far more vegetables without much or any meat for most of the year in ancient times.

JW: Mr. Serra, I thank you so much for your time and consideration. On behalf of everyone at AHE, I wish you many adventures in research and a happy holiday season! God Jul!

DS: Thanks James! It was interesting to speak with you. Questions are always good for fuelling more thoughts and formulating new questions or approaches to the material. My next culinary adventure will be to update our old book En sås av ringa värde, based on a Danish medieval culinary manuscript, and translate it into English.

I wish you and your readers a great holiday season with many old and new culinary experiences.

Nota Bene: If you are interested in trying out some Viking recipes, AHE also recommends taking a look at these PDF files from Tjursläkter and the New Varangian Guard, as well as this link from the Viking Answer Lady and this link from the British Museum.

Historical food in all its forms has been a part of Daniel Serra‘s life since 1994. As a young archaeology student, he sampled the flavors of ancient Rome by recreating dishes from the Roman cookbook by Apicius. This first encounter with tastes from the past led to a great curiosity for historical foods and a profound academic interest in culinary history. He has since studied, reconstructed, lectured, cooked and tasted his way from Iron Age to Renaissance food, and is now considered an authority on Viking Age and medieval food by museums and reenactors in Scandinavia. Daniel’s research spans from the Viking Age to the Renaissance and is concentrated on taste, culinary practices, and the role food has played in ancient societies. Through archaeological findings, written sources, and experimental cooking projects, he has acquired the comprehensive knowledge that is the basis for his doctoral dissertation and An Early Meal: A Viking Age Cookbook & Culinary Odyssey, in which he gives us a taste of history. In Daniel’s own words: “We meet, remember and express ourselves through food. Culinary culture allows us to understand and experience the world around us.” As an experimental archaeologist, Daniel was employed in 2010 to reconstruct Viking Age food at the Lofotr Viking Museum in Lofoten, Norway and Renaissance food in 2011 at the Glimmingehus Museum in Simrishamn, Sweden. Daniel has given lectures, courses, workshops, and consulting tips about food archaeology and culinary history through his company Memento-Past Food for ten years.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by Daniel Sera or ChronoCopia Publishing have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Thanks is given to Mr. Rikard Aklam of ChronoCopia Publishing for his assistance with the images found within the interview. Translations from Swedish were undertaken by James Blake Wiener. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.