Whoever was privileged to gain access to the North Palace of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, could consider himself part of something timeless. Thanks to the great work of Hormuzd Rassam (1826-1910), who unveiled a large number of alabaster bas-reliefs, which once decorated the walls of that king’s Palace (built around 645 BCE); the Assyrian lion-hunting scenes!

These extraordinary carvings, so dynamic and full of movements, are so realistic and so accomplished and are some of the most remarkable ancient artifacts ever found. They were discovered by Rassam in the year 1853 and have been housed in the British Museum since 1856. Rassam stated in his autobiography that “one division of the workmen, after 3-4 hours of hard labor, were rewarded by the grand discovery of a beautiful bas-relief in a perfect state of preservation”. Rassam ordered his men to dig a large hole in the mound; after more than 2,000 years, the remains of a royal palace were found. The mud-bricks had disappeared, of course, completely but the reliefs themselves, which once decorated them, have fortunately survived.

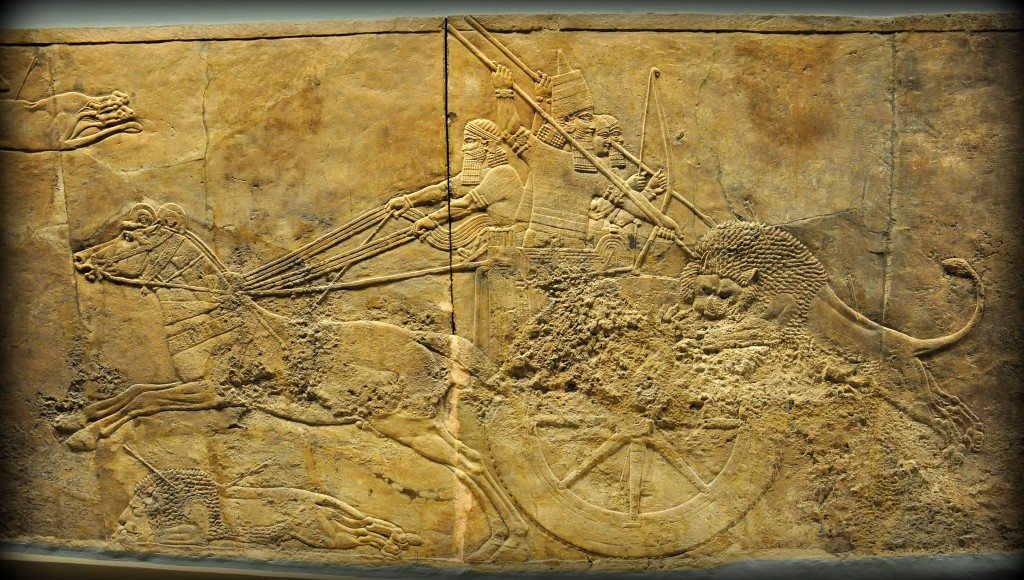

Detail of an alabaster bas-relief depicting the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. The king is identified by his conical head cap. He holds a bow and throws arrows towards a succession of lions. Note the exquisitely carved embroidery, armlets, earring, and costume. His royal attendant is guiding the royal chariot. The eyes of the king and his attendant were intentionally damaged after the fall of Nineveh. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Ashurbanipal

At the heart of the Assyrian galleries, Room 10a of the British Museum in London, these stone slabs stand on either wall of the room. They depict a group of warriors led by a taller figure, who wears a conical hat; this is their king. The men appear to hunt a large number of lions. Rassam, initially, did not recognize who is the king. He made copies of the cuneiform inscriptions written on the Palace’s reliefs and sent them to Henry Rawlinson (1810-1895), the British consul in Baghdad. Rawlinson could read cuneiform and wrote back to Rassam saying that this is a palace of Ashurbanipal; nothing was much known about Ashurbanipal when his name first came to light!

Detail of an alabaster bas-relief depicting the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. The king is identified by his conical head cap. He holds a long spear and stabs a leaping lion in his head. Note the exquisitely carved embroidery, armlets, earring, and costume. Two royal attendants ward off the lion with their spear. One of his royal attendants is guiding the royal chariot. The eye of the king was intentionally damaged after the fall of Nineveh. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

It is believed that the objective was not to generate pity for the dying creatures but rather to highlight their raw, dangerous presence and to show how they collapse in agony at the hands of the Assyrian king who, through the support of the gods and his skill with weapons, brings civilization to the chaotic and disordered world that the animal represent.

Ashurbanipal was depicted many times (riding a royal chariot, standing on his feet on earth, and on the back of his galloping horse); his overall costume, face, beard, and gestures were carved very exquisitely and vividly. But even though the king does matter a lot; it is these lions which form the core of the scenes.

A single artist is thought to have created these reliefs, helped by many assistants; it is also thought that the king himself might at times intervened in order to add/change some of the details of the imagery. The hunt scenes, full of tension and realism, rank among the finest achievements of the Assyrian Art. They depict the release of the lions, the ensuing chase, and their subsequent killing.

Although very brutal and bloody, the “massacre” appears very beautiful! Was this the intention of the sculptor? These slabs decorated both walls of a corridor within the palace (Room C) and a private gate-chamber (Room S). Apart from the king, his courtiers, and some of his visitors, who else could have accessed them? The public? Whom to impress, in other words? The sculptor was cleverly pointing out the contrast between the cruel king and his noble victims; however, the people for whom the scenes were designed saw the king as the paragon of nobility, and the lions as cruel enemies that should deserve painful, and even ludicrous, slaughtering.

The first documented scene of lion-hunting dates back to 3000 BCE; it was about a ruler who was hunting lions. The North-West Palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (883-859 BCE) housed few lion-hunting scenes, indicating that this act had been present for ages.

The hunting environment, Room C:

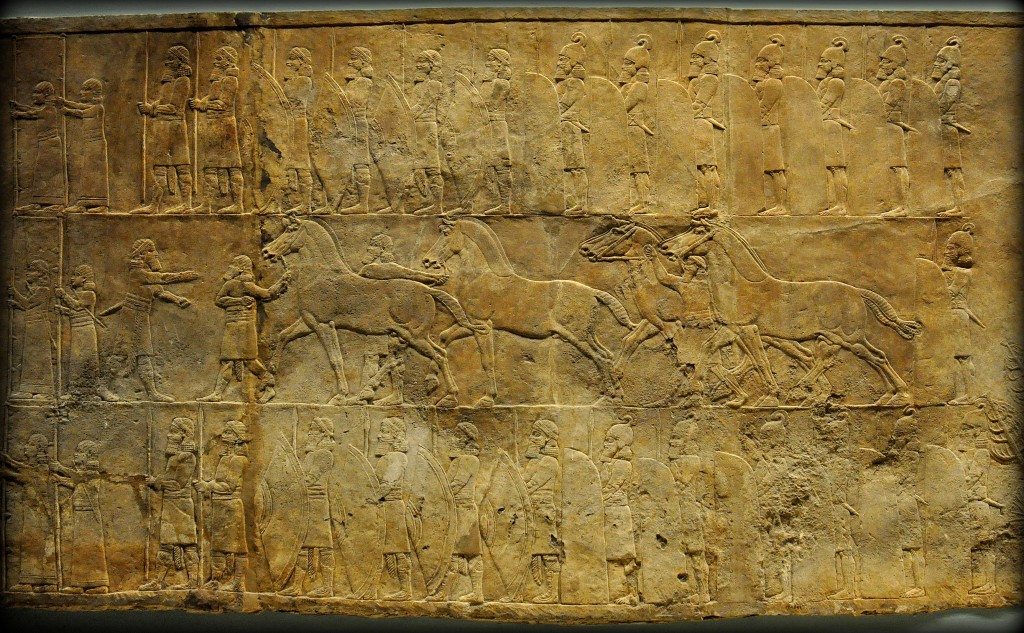

The arena is ringed by a double line of soldiers with high shields and bows/arrows, and at some points with keepers with dogs, to prevent lions escape the arena. The target audience, the public, is watching from a hill; men and women are scrambling up the slope, either in terror or to reach a point with a good view of the action that is about to begin. Meanwhile, the king and his accompaniments prepare themselves for the action; horses, bows, spears, and so on.

The lions and lionesses are not free within the wild forest; they are brought to the arena inside cages; this indicates that the animals were captured beforehand. A person, usually a child, lifts the trapdoor and releases the lion. Nearby horsemen drive/lure the lions towards the king and his guards to face their final destiny through a multitude of vivid, cinematic, and remarkably depicted painful scenes. The lions were depicted in many attitudes of fighting death (receiving and hit by arrows, spears, and/or swords) or they were already dead. The animals’ facial expressions and eyes were depicted in a very realistic way of horror, defeat, and agony. Overall, there are 18 lions/lionesses in this Room.

- Alabaster bas-relief depicting keepers with dogs. Those keepers were stationed at some points at the edge of the arena, in front of the line of soldiers. The intention is the same; deterring lions from trying to escape. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-535 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

- This alabaster bas-relief depicts a double line of soldiers. The front line holds high shields while the rear one has bows. This line surrounds the arena like a ring to prevent any lion escaping the arena. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

In this alabaster bas-relief, grooms appear to lead horses towards a screened enclosure within which a royal chariot is being prepared for the hunt. Men are struggling to push one of the horses into position while another horse is having his harness tightened. Soldiers protecting the arena are ready. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

- In this fragment of a larger alabaster bas-relief, men appear to prepare bows for the hunt. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-535 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

- The action is about to begin; let’s rock! In this alabaster bas-relief, a child lifts up a trapdoor, releasing a lion from his cage. The child himself has a small cage for protection. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-535 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

In this alabaster bas-relief, the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal stands in his royal chariot while his men do the necessary preparations before the hunt starts. His left hand rests on his sword’s hilt. The king’s face was deliberately vandalized after the fall of Nineveh. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

- In these panels of alabaster bas-reliefs, horsemen (upper-right part of the panels) appear to drive/lure lions towards the king’s chariot. After approaching the chariot, the lions will be hunted/killed. In this relief, two lions and two lionesses were hit by many arrows and are already dead; note their flat facial expressions, closed eyes, and different postures. The third lion, who is already hit by an arrow in his head, is jumping and leaping towards the royal chariot. He receives two spears from the king’s attendants, who are trying to ward him off the chariot. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-535 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

- In this alabaster bas-relief, the king’s chariot is chasing lions. The king holds a bow an shoots arrows towards a succession of lions. A dead lioness appear beneath the chariot’s galloping horses. The two royal attendants are warding off a lion attacking from behind. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-535 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

This alabaster bas-relief depicts Assyrians climbing a hill. People seem to rush up a wooden knoll, either in fright or to get a better view. The hill is crowned by a building, monument, or stela, which is decorated with another picture of the royal hunt scene. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Alabaster bas-relief depicting a dying lion. He has been hit by four arrows; blood gushes from the entry and exit points of the arrows. One of the arrows has passed through the left shoulder; note the limping of the left foreleg. The lion also appears to vomit blood! His facial expression of agony and fear is very well reflected; note how he looks forward. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Alabaster bas-relief depicting a dying lioness. The lioness has received three arrows; blood can be seen gushing from the ensuing wounds. One of the arrows hit her at the lower back; this may explain her hind legs’ weakness! She is roaring in agony, fighting death. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Alabaster bas-relief showing Ashurbanipal in his royal chariot hunting a lion. The lion has been already hit by two arrows and he has leaped towards the rear part of the chariot. Two royal attendants – one holds a bow and the other one holds a spear – are trying to ward the lion off the king. The king holds a long spear with two hands, thrusting forcefully upon the lion’s head; the lion tries to turn his head away. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Detail of an alabaster bas-relief showing a lion being stabbed in the neck. The lion has jumped and reached a critical point, very close to the king’s chariot. The king’s attendants thrust their spears into the lion’s neck to stop the lion; the king, using his right hand, stabs the lion deeply into his neck using a sword. The lion’s painful facial expression was depicted very delicately. The king’s bracelet also clearly appears. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Fragment of an alabaster bas-relief showing six men carrying a dead lion at the end of the hunt. From Room C of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

The hunting environment, Room S:

This private chamber-gate was decorated with relatively small scale hunt scenes, arranged in three parallel horizontal registers. None of the scenes here depicts a royal charter. Instead, the king appears to stand on earth or ride a galloping horse; he wears a diadem, not the typical conical head cap of Assyrian kings.

Alabaster bas-relief showing Ashurbanipal thrusting a spear onto a lion’s head. This is one of the very anxious moments which was carefully conveyed to us by the artist! The register is part of three relatively small-scale registers. The king’s spare horse was attacked by a wounded lion that had been left for dead. The king himself is busy with another furiously attacking lion. The king’s attendants (not shown in this picture) lagged behind and galloped desperately to rescue their king (from the left side of the panel). The sculptor used empty spaces (before and behind the king) to dramatic effect, one of the features that sets Ashurbanipal’s hunt scenes apart from the general run of Assyrian sculpture. The king was left alone, facing a deadly moment! From Room S of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

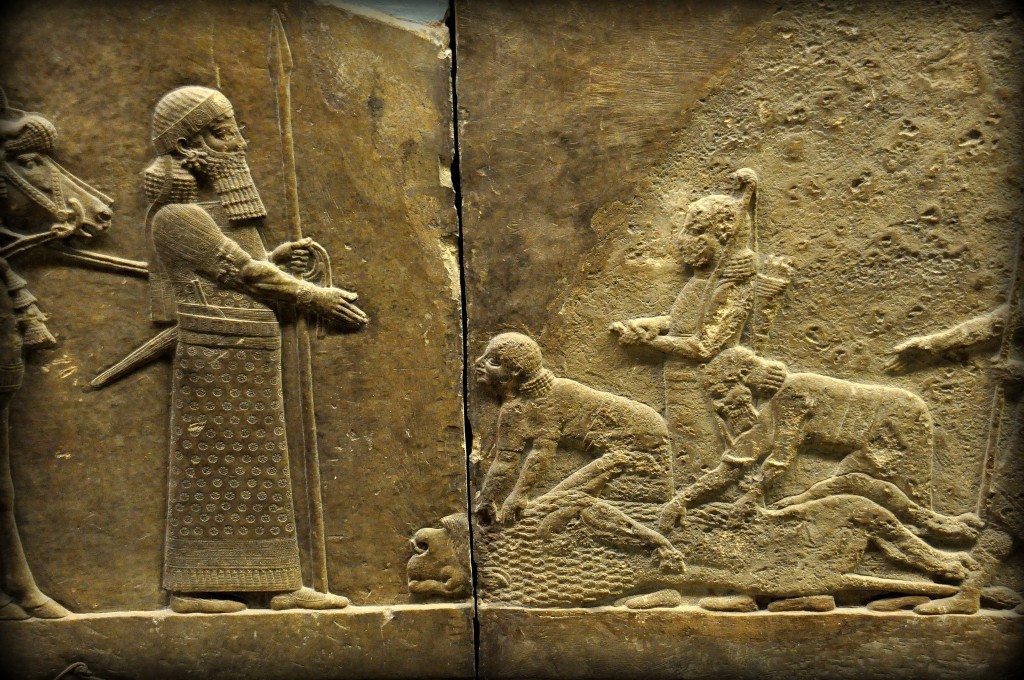

Alabaster bas-relief showing Ashurbanipal on foot before dead lions. This register is the continuation of the above scene to the right. The king has coped with the emergency and killed the two lions. Some of the royal attendants exclaim at the size of the dead lions; one attendant looks at his master. The king holds his spear and the horses’ rein with his left hand. He appears to speak to his courtiers, pointing out using his right hand. The king and his two horses have survived! From Room S of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Detail of an alabaster bas-relief showing Ashurbanipal’s horses. This is part of the above image. Note how beautiful and elegant they are! From Room S of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Alabaster bas-relief showing Ashurbanipal stabbing a wounded lion. This is one of the very vivid moments which speaks clearly on its behalf without any narration. The king, on foot, wearing his elegant costume and accessories, grips the lion’s neck firmly with his left hand while the right hand stabs a sword rapidly and deeply into the lion’s belly. The king, rigid-faced, and the, lion roaring in fear and agony, look at each other. The king’s attendant holds a bow and arrows but does not seem to do anything to protect his master; it is not credible that the king exposed himself to mauling from a slightly wounded but still vigorous and aggressive lion in the way that this sculpture, viewed in isolation, implies. The lion is in a very close proximity, almost touching the king with his sharp paws. From Room S of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Alabaster bas-relief showing Ashurbanipal rescuing foreign princes from a lion. Those princes, the men on the right of the panel, are kneeling and throwing their bows before the king; they came to the Assyrian capital as political refugees. Ashurbanipal took them off to shoot lions, but they had missed, and he is shooting over their heads. There will have been a charging lion on the lost panel to the right. From Room S of the North Palace, Nineveh (modern-day Kouyunjik, Mosul Governorate), Mesopotamia, Iraq. Circa 645-635 BCE. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

The king himself uses a variety of weapons, reflecting his superb abilities; a bow, sword, and spear. He was depicted three times on his royal chariot, guarded and helped by his men. At times, the king stands on his feet on earth and kills lions with a sword. He also rides a horse and uses a bow/spear to kill his prey. In one relief the king grasps a leaping lion from his neck with his left hand and stabs the lion forcefully and deeply with his sword in his right hand in a very dramatic event.

In all scenes, the king and his men appear rigid-faced and heartless. Had the king really faced these aggressive animals so closely and threatened his life? Had these men, all of them, encountered this large number of hostile animals, using their spears, arrows, and swords only? The artist/sculptor documented some “unexpected” and dangerous moments the king had faced. The reliefs from Room S were carved in three parallel registers and different scenes while the events on Panels from Room C occupied the whole slabs.

I was attending a symposium at the Royal College of Physicians of London. It was a great opportunity to visit, see, and feel this marvelous art from my land, Mesopotamia (Iraq)!

Bibliography & Thanks

The following were used to draft this article:

- Reade J. Assyrian sculpture. London: The British Museum Press; 2013.

- Collins P, Baylis L, Marshall S. Assyrian palace sculptures. London: The British Museum Press; 2012.

- The Assyrian lion hunt reliefs. A BBC documentary on masterpieces of the British Museum, episode 2 of 6, 30 minutes.

- Personal visit to the British Museum.

As an Iraqi citizen, I would like to sincerely thank all of those who were involved in the excavation, transportation, preservation, protection, and the display of this world-class ancient art! This history belongs to the whole world and humanity, not only to Iraq. Viva Mesopotamia, the Cradle of Civilization!