There are two Paleolithic caves in Iraqi Kurdistan (the northeast area of the Republic of Iraq): Hazar Merd and Shanidar. Iraq, the cradle of civilization, has become a dangerous destination for tourists. Instead of discussing their deep archaeological details, I will you take on a cyber-tour to see these caves.

Hazar Merd Group of Caves

Hazar Merd Cave (Kurdish: هه زار ميرد ; Arabic: هزار مرد) is located in the area where I live. Each and every day, when I go to work at 8 AM, I see the mountain which houses the cave. It is located within the Governorate of Sulaymaniyah. It lies 13 km (35°29’39.22″N; 45°18’37.66″E) to the west of modern-day Sulaymaniyah city, Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

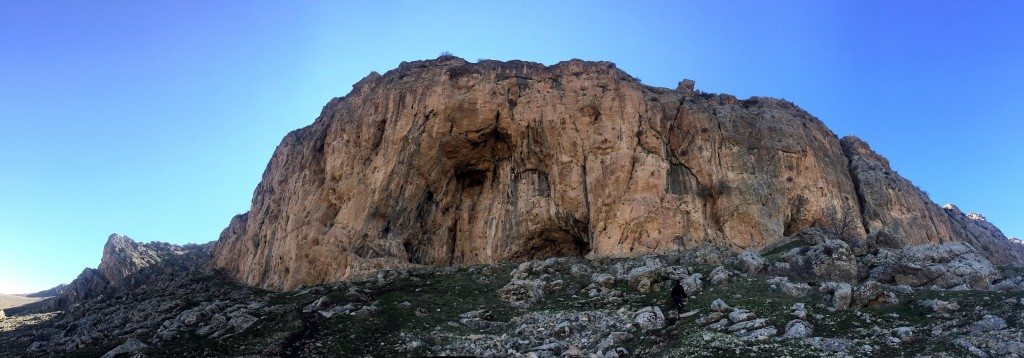

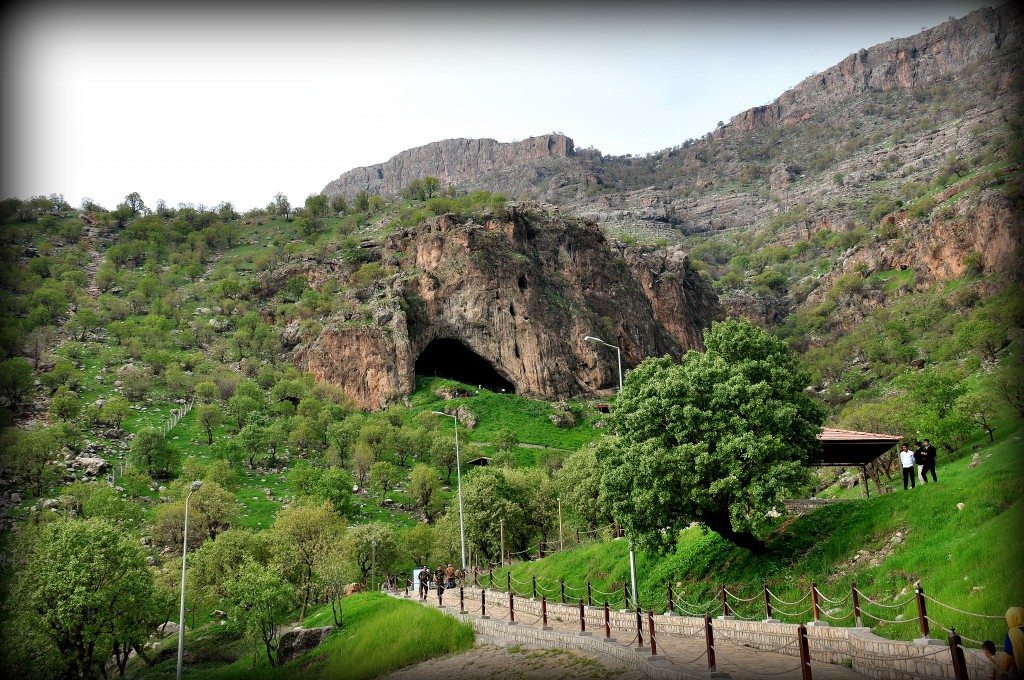

It is not a single cave, but rather a collection of adjacent caves of various sizes within a cliff of a small mountain. The usual destination for tourists is two caves; the largest cave (see the image below) and an adjacent cave to the left of it (Ashkawty Tarik in Kurdish, “the Dark Cave”), where most of the excavation works were conducted. The cave appears to date back to 50,000 years BCE.

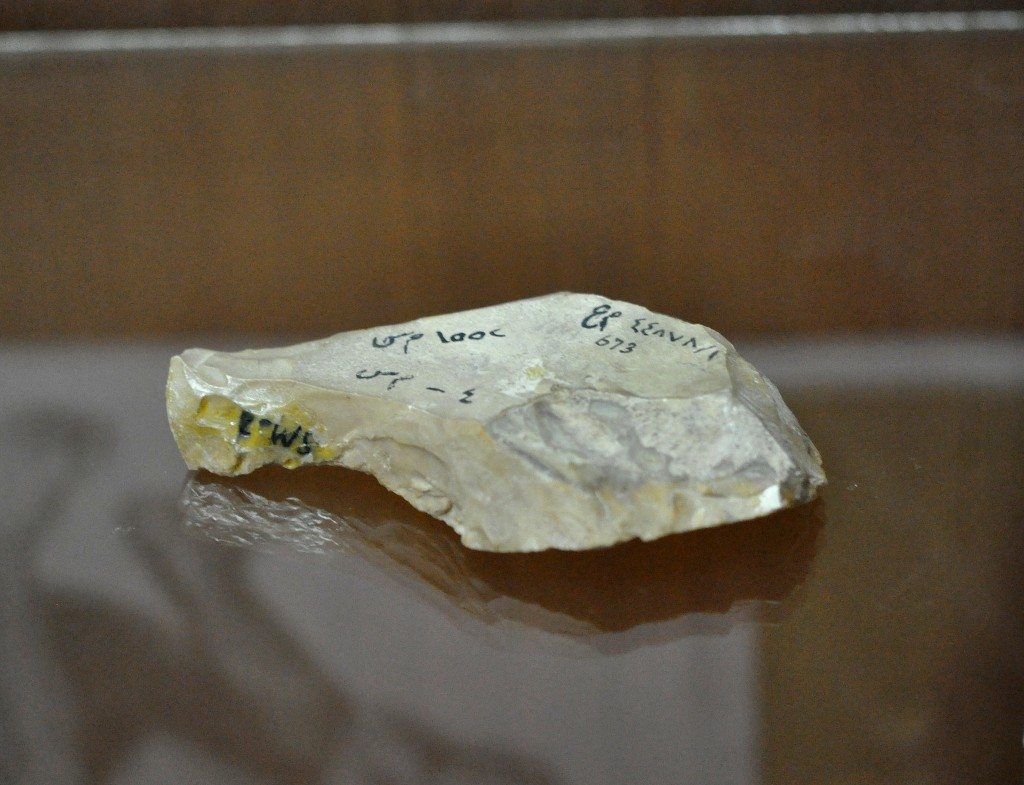

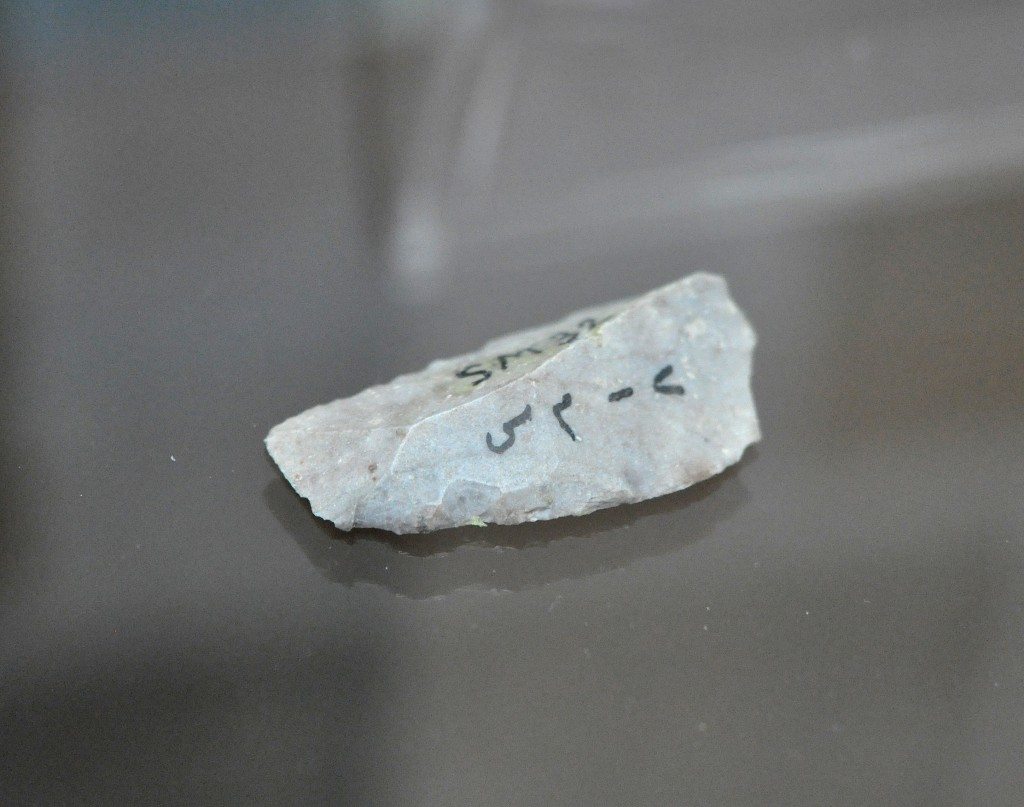

In 1928, the British archaeologist Dorothy Garrod (1892-1968) conducted a short-term excavation in the caves. She unearthed hand-axes, animal bones, and other stone tools, but no human remains were found. Some of these artifacts are housed in the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad and in the Sulaymaniyah Museum in Sulaymaniyah Governorate of Iraqi Kurdistan. Nowadays, the site is very easily accessible! I go there every now and then with my daughter.

Heading from Sulaymaniyah city to Hazar Merd caves. The largest cave appears clearly within the cliff of the mountain. The smaller cave next to it (on the right side of the viewer) is Ashkawty Tarik (Kurdish for “The Dark Cave”). These two caves were excavated by Dorothy Garrod in 1928. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Hazar Merd caves can be seen on the cliff of this low mountain. A road has been made and this makes it easier to drive very close to the caves. You can bring your car but you have to climb about 20 meters to enter the caves. Not exhaustive though! Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Panoramic view of Hazar Merd caves. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

At the mouth of the largest cave of Hazar Merd caves. The two young men at the right side were preparing their hookah! Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The mouth of the largest cave at Hazar Merd. The other cave, Ashkawti Tarik or “Dark Cave,” lies immediately behind me. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Within the left wall of the largest cave, there is a relatively small room; someone used spray paint to write “Ohh Allah.” (Arabic: يا الله). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Rounded, cylinder-shaped pit within the floor of the largest cave at Hazar Merd. Another pit is present near this one. It might have been used for cooking purposes. I found a very similar pit within Shanidar Cave. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Passing through this small path, from the largest cave to Ashkawty Tarik. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The entrance into the other cave, Ashkawty Tarik (“The Dark Cave”). The entrance of the cave is much smaller than the previous one, but it is deeper and tube-like. The main excavations were done here. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The entrance of the dark cave of Hazar Merd, shooting from inside. The caves look over the city of Sulaymaniyah (at a distance of 13 km). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Inside Ashkawty Tarik, one of the caves of Hazar Merd. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This is where the dark cave of Hazar Merd ends. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

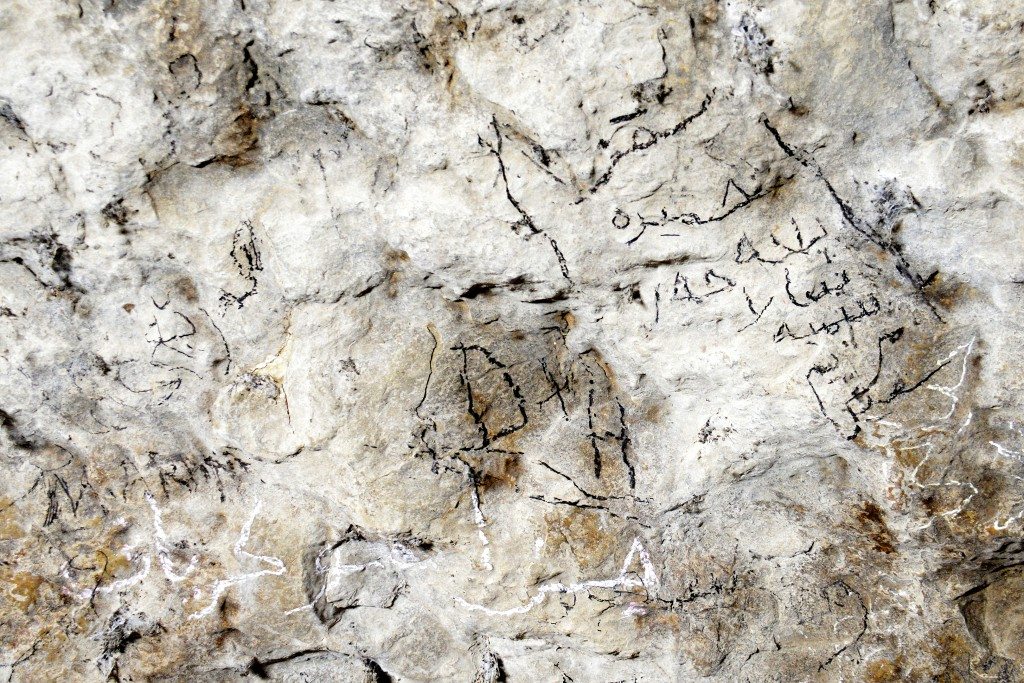

Visitors have left their memories by writing their names (in Kurdish and English letters) on Ashkawty Tarik’s walls. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A stone hand-axe dating back to the Paleolithic era that was found at the Hazar Merd cave. It is housed in the Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A stone blade dating back to the Paleolithic era that was found at the Hazar Merd cave. It is housed in the Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

[embedyt] http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gMH1PU0MlKY[/embedyt]

Shanidar Cave

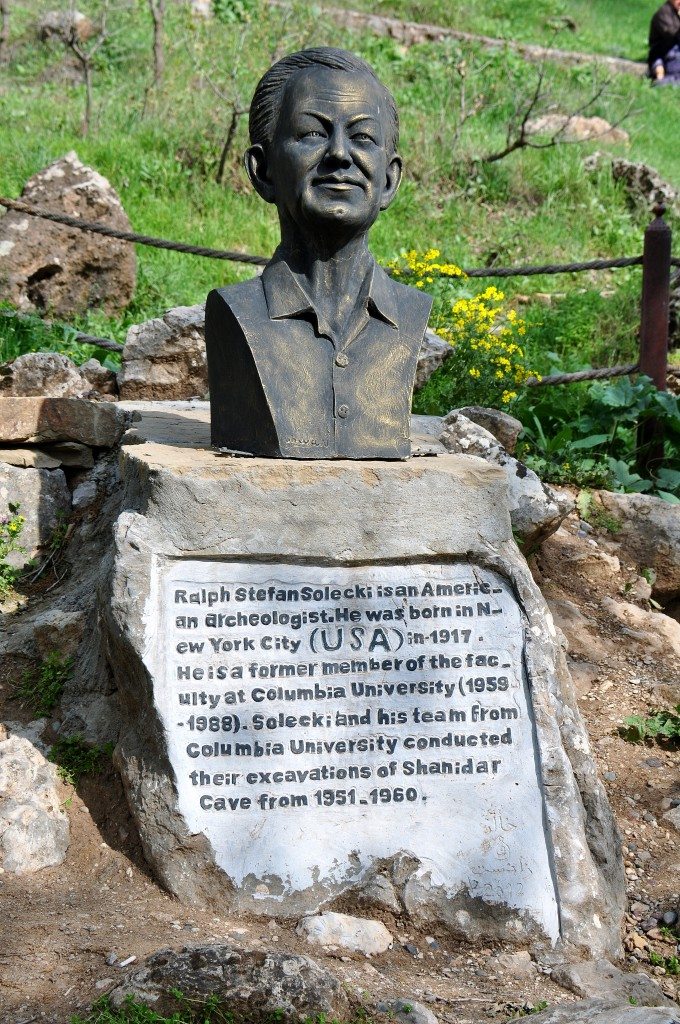

Shanidar Cave (Kurdish: ئەشکەوتی شانەدەر ; Arabic: كهف شاندر) lies on the cliff of the mountain Bradost, in Zagros range, 762 meters above sea level. It is about 125 km north (and somewhat east) of Erbil (Hawler) city, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan. Archaeologist Ralph Solecki conducted four extensive excavation seasons from 1951 to 1960 within the cave.

In 1950, Ralph was a graduate student at Columbia University. He was interested in exploring Middle East caves; the information he obtains after then will help him do his thesis. He arrived in Iraq in 1950. Local Kurdish people advised him on how to reach out an old cave within a mountain and history changed as a result. He recalled his memories about excavating in Shanidar Cave to the the Wall Street Journal in 2013.

The first human skull was unearthed in 1957. The remaining skeleton revealed that it was a male, about 40 years old at the time of his death. Ralph named him Nandy, short for Neanderthal. Over the next three years, three other skeletons were found. The last one seemed to be buried with flowers. All of them were males and their skeletons are housed in the Iraqi Museum, Baghdad, Iraq. I surfed the net and tried to find out whether those human remains were lost during the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq and the dramatic looting of the Iraqi Museum, but I failed. In total, nine “Shanidar skeletons” have been found; all of them are in the Iraqi Museum with the exception of “Shanidar 3,” which is housed in the Smithsonian Institute. In 2006, some bones belonging to a single skeleton were found at the Smithsonian Institute and scientists designated this as “Shanidar 10.”

Reynolds and colleagues did some excavation work during 2014-2015 inside Shanidar cave and their findings were published very recently in Antiquity Journal. They found many different human bones belonging to a what appears to be a single body. It is unclear whether these bones are part of “Shanidar 5” skeleton or they represent a newly discovered individual.

During his excavations, Ralph dug a trench and reached a depth of 14 meters. The work unveiled four civilization cycles dating back to the stone ages, around 60,000-80,000 years BCE.

How did our ancestors live there? How they were communicating with each other? Within these caves, people were living, day by day, and year by year. They ate, drank water, made food, had sex, gave birth, raised children, got sick, had injuries, laughed, cried, and eventually died! I sat on the verge of the caves’ entrance and stared at the valley, and then closed my eyes, opened my ears, and listened to the blowing wind, hoping that I would get a call from the souls of the people who lived there. My body was numbed!

Shanidar Cave. The cave and its surrounding area has been renovated by the Kurdistan-United Kingdom Friendship Association. Tourists have an easy access to the cave. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Shanidar cave’s entrance is on left side of the viewer. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The cave’s entrance. It seems that the fence was placed to prevent wild animals from entering it; I saw many cows nearby! Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Inside Shanidar Cave. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

What a coincidence! The same hole at the Shanidar cave! Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Inside the Shanidar cave. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Ralph Solecki’s memorial at the Shanidar Cave. Solecki was born in 1917 in Brooklyn, New York. He is still alive at the time of drafting this article, as far as I know. Solecki unearthed the first Neanderthal’s skull in the spring of 1957 in one of the caves. It is not mentioned who sculpted this bust. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Disclaimer:

Erbil (or Hawler) Governorate and Sulaymaniayh Governorate lie within the northern area of Iraq and is part of Iraqi Kurdistan (or Kurdistan Region or Southern Kurdistan). All of these terms are used to describe the region. Neither the author nor Ancient History Encyclopedia endorses any specific term of the aforementioned ones.