I was attending an event at the Royal College of Physicians of London in early March 2016, and I had a plenty of time to spare. One of my targets was, of course, the British Museum. Two years ago, Jan van der Crabben (founder and CEO of the Ancient History Encyclopedia) asked me to draft a blog article about the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, but I lacked detailed and high-quality images of all aspects of the obelisk. Nowadays, I’m equipped with a Nikon D750 full-frame camera and incredible lenses. So let’s spend some time looking at the obelisk and enjoy its wonderful artistic scenes.

The obelisk lies at the heart of Room 6 of the Ground Floor. The overall surrounding lighting is unfortunately scarce, but who cares, my camera can overcome this very easily! Remember, no “flash” photography is allowed.

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III at Room 6 of the Ground Floor of the British Museum, London. We can see side A (right, beginning of the scenes) and side D (left, end of the scenes). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

In December 1846, while working with his excavation team at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu or biblical Calah), located in northern Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq, Sir Austen Henry Layard discovered the obelisk. It was in a perfect state of preservation and is still considered the only complete Assyrian obelisk ever found. It was later on transferred to the British Museum (BM “Big number” 118885; Registration Number 1848,1104.1).

The obelisk is a black limestone stela or a monument. It was erected in the year 825 BCE within the courtyard of the so-called “Central Building” within Kalhu (the Assyrian capital at that time) as a public monument during a civil war and turbulence . The obelisk is 197.48 cm in height, 81.91 cm height (of plinth), and 45.08 cm in width. The top was made in the shape of a ziggurat.

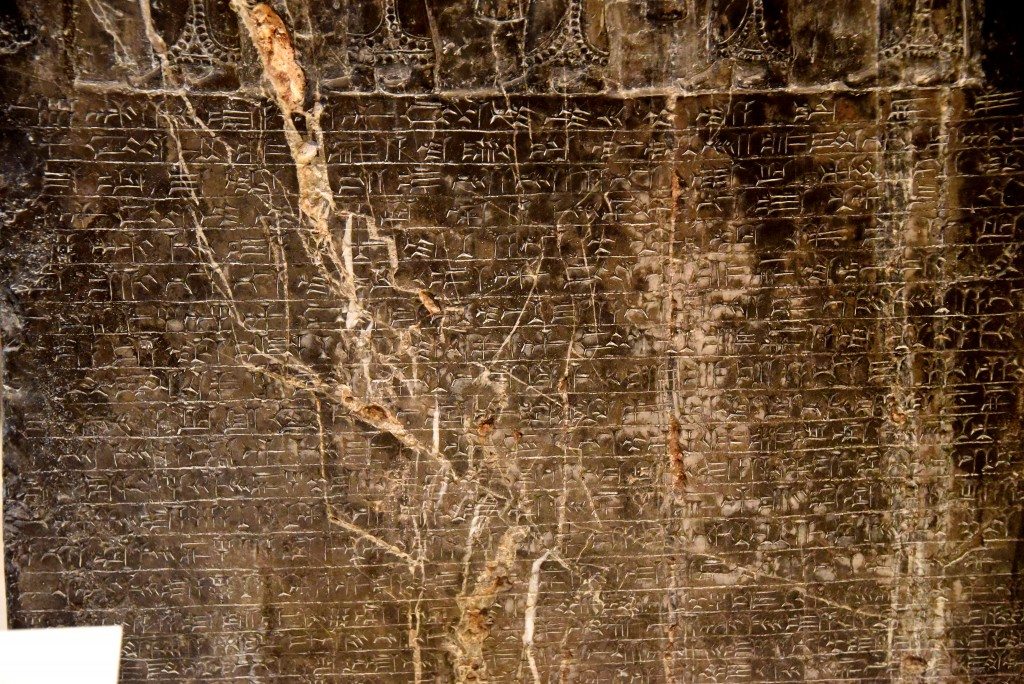

The ziggurat-shaped top of the Black Obelisk, sides A (right) and D (left). Note the Akkadian cuneiform inscriptions. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The obelisk commemorates 31 years of military campaigns conducted by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (reigned 858-824 BCE). The obelisk has four sides. On each side, we can see five vertically arranged registers (or scenes). Each scene tells a story about a subdued king or ruler, who is paying tribute and prostrating before the victorious Assyrian king Shalmaneser III; however, two out of the five kings were depicted on the registers. Each individual scene narrates horizontally, using Akkadian cuneiform inscriptions and carved reliefs, from one side to another (in an anti-clockwise manner), wrapping around the obelisk. Therefore, there are five stories from top to bottom, in 20 registers.

There are cuneiform the inscriptions carved on the base of the Obelisk. This is side A. Note the damages incurred during the transportation of the Obelisk. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The obelisk became historically important because it depicts and documents Jehu of the House of Omri (king of Israel), and therefore, a biblical figure.

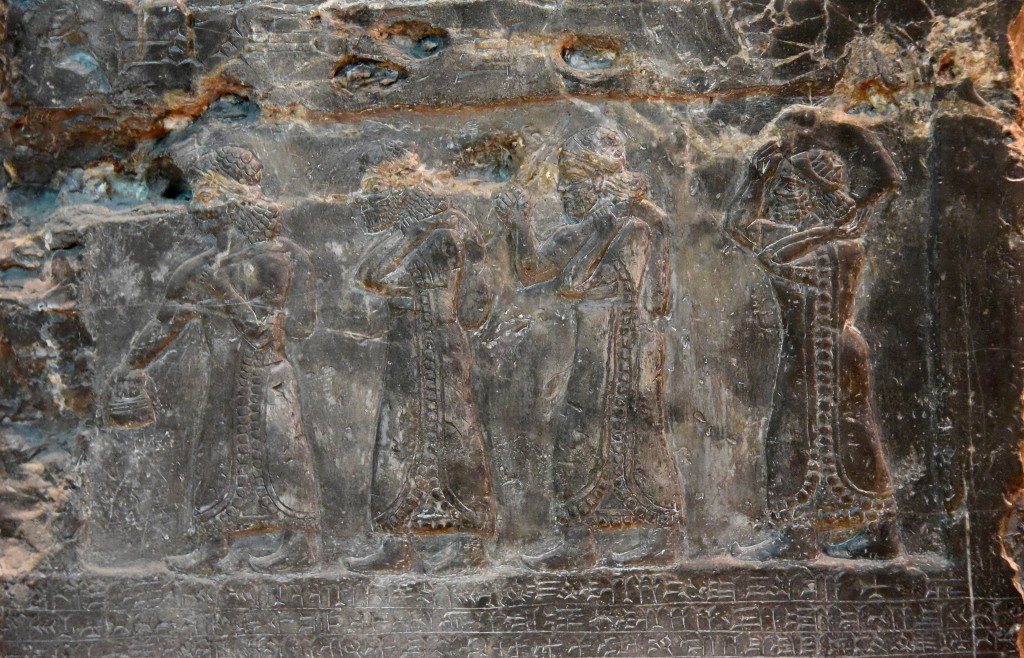

Jehu (son of Omri), king of Israel, bows and prostrates before Shalmaneser III. The Assyrian king is accompanied by four attendants. Jehu is thought to be a biblical figure. Detail of the Black Obelisk, Side A, register 2. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Jehu (son of Omri), king of Israel, bows and prostrates before the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (not shown). An Assyrian attendant stands behind Jehu. Jehu is thought to be a biblical figure. Detail of the Black Obelisk, Side A, register 2. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

I will describe each horizontal scene (from top to bottom), not the individual sides separately.

Scene 1: King Shalmaneser III receives tribute from Sua of Gilzanu (of modern day north-west Iran): Shalmaneser says that I received tribute from Sua the Gilzanean, silver, gold, tin, bronze, cauldrons, the staffs of the king’s hand, horses (and) two-humped camels.

Side A: King Shalmaneser III holds a bow and receives tribute from Sua the Gilzanean (who bows before the king). Two attendants stand behind the king. The king looks at his field marshal and another unnamed official. Symbols of gods Assur (right) and Ishtar (left) are seen before the king’s head. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are two Assyrian officials, a foreign groom, and a horse with rich trappings (which represent the horses for which Gilzanu was famous). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: Two men bring two-humped (Bactrian) camels from Gilzanu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: There are five tribute-bearers bringing silver, gold, tin, bronze cauldrons (and) the “staffs of the king’s hand” from Gilzanu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Scene 2: King Shalmaneser III receives tribute from Iaua (Jehu) of the House of Omri (ancient Israel): Shalmaneser says that “I received tribute from Iaua, son of Omri. Notice that one can see silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden tureen, golden pails, tin, the staffs ‘of the king’s hand’ and a spear.”

Side A: King Shalmaneser III stands beneath a parasol (held by an attendant) and receives tribute from Iaua of the House of Omri (in the year 841 BCE). This is King Jehu of Israel, who appears in the Bible (2 Kings 9-10). An attendant faces the king and holds a fly whisk. There are two guards at both sides. Symbols of gods Assur (left) and Ishtar (right) are seen before the king’s head. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are two Assyrian officials and three tribute-bearers from Israel; they hold “silver, gold … gold vessels … tin …” Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: There are five more tribute-bearers from Israel bringing a gold bowl, a golden tureen, gold vessels, gold pails, tin, the “staffs of the king’s hand” (and) spears. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: There are five tribute-bearers from Israel holding silver, gold, a gold bowl, a gold tureen, gold vessels, gold pails (and) tin. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Scene 3: A parade of exotic animals brought from the land of Musri (probably Egypt); there is no depiction of the subdued king or ruler, whose name was not mentioned). Shalmaneser says that “I received tribute from Muṣri, two-humped camels, a water buffalo, a rhinoceros, an antelope, female elephants, female monkeys and apes.”

Side A: Attendants bring tribute from Musri in the form of two-humped camels. Unlike the upper registers on side A, neither Shalmaneser III nor the subdued ruler appear. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: This register depicts exotic animals from Musri in the form of a river-ox, a rhinoceros (and) an antelope. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: There are female elephants, female monkeys (and) apes. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: There are more monkeys with their keepers. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Scene 4; Marduk-apla-usur the Suhean (from the mid-Euphrates area of modern-day Syria and Iraq), sends animals and other tribute to the Shalmaneser III (the former was not depicted on the Obelisk). Shalmaneser says that “I received tribute from Marduk-apla-usur, the Suhean, silver, gold, pails, ivory, spears, byssus, garments with multi-coloured trim and linen.”

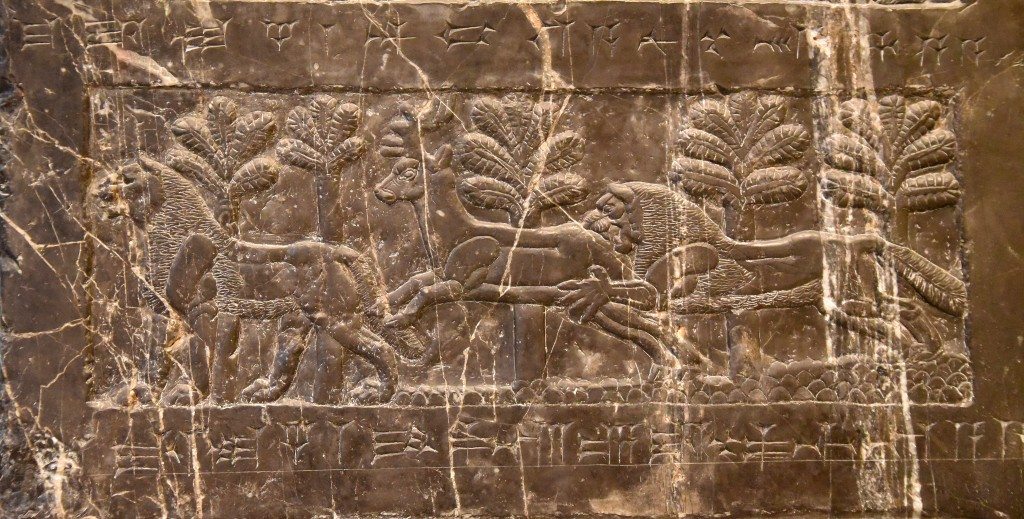

Side A: There are two lions and a stag from Marduk-apla-usur the Suhean (probably for the royal hunting park). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are four tribute-bearers from Suhu carrying “silver, gold… byssus, garments with multi-colored trim and linen.” Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

![Side C: We can see 5 tribute-bearers bringing "silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears" from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.](http://etc.ancient.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OSA_7096-1024x587.jpg)

Side C: We can see five tribute-bearers bringing “silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears” from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

![Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted carrying "silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears" from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.](http://etc.ancient.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OSA_7083-1024x720.jpg)

Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted carrying “silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears” from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

![Side A: Tribute from Qarparunda the Patinean in the form of silver, gold, tin, ”fast” bronze ... ivory [tusks] (and) ebony. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.](http://etc.ancient.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OSA_7072-1024x588.jpg)

Side A: Tribute from Qarparunda the Patinean in the form of silver, gold, tin, “fast” bronze … ivory [tusks] (and) ebony. Qarparunda was not depicted on the scene. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are two Assyrian officials introducing three tribute-bearers from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: We can recognize five tribute-bearers bringing “gold and silver” vessels and a “bronze cauldron” from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted holding “gold and silver” vessels and a “bronze cauldron,” which were brought from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The following were used to draft this article:

- Images from a personal visit to the British Museum and the British Museum website description of the Obelisk.

- Jonathan Taylor, ‘The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III’, Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org.

- The Bible in the British Museum.

- P. Kyle McCarter’s article on Yaw, Son of Omri, which is accessible through JSTOR.

I hope I have been successful in conveying the images of this obelisk to you! As an Iraqi citizen, I would like to sincerely thank all of those who were involved in the excavation, transportation, preservation, protection, and the display of this Black Obelisk. This history belongs to the whole world and humanity, not only to Iraq. Viva Mesopotamia, the Cradle of Civilization!