On a recent trip to southern Spain, I travelled along the Roman Baetica Route and visited many of the archaeological sites and museums that Andalusia has to offer. Among the plethora of ancient treasures to be found in the region, I was particularly impressed by the incredible mosaics I came across.

The Roman Baetica Route is an ancient Roman road that passes through fourteen cities of the provinces of Seville, Cadiz, and Córdoba, which correspond to modern-day Andalusia. It runs through the most southern part of the Roman province of Hispania and includes territories also crossed by the Via Augusta. The route connected Hispalis (Seville) with Corduba (Córdoba) and Gades (Cádiz). The word Baetica comes from Baetis, the ancient name for the river Guadalquivir.

The Roman Baetica Route

Before the arrival of the Romans, the area was occupied by the Turdetani, a powerful tribe and, according to Strabo, the most civilized peoples in Iberia. The south of the Iberian peninsula was fertile and agriculturally rich, providing for export wine, olive oil and garum (the fermented fish sauce). The economy was based mainly on agriculture and livestock, along with mining. This economy formed the basis of the Turdetani’s trade with the Carthaginians who were established on the coast. The Romans arrived in the Iberian peninsula during the Second Punic War in the 2nd century BC, and annexed it under Augustus after two centuries of war with the Celtic and Iberian tribes. Soon, Baetica became the most romanized province in the Peninsula.

Hispania Baetica was divided into four territorial and juridicial divisions (conventī): the conventus Gaditanus (of Gades – Cádiz), Cordubensis (of Corduba – Cordoba), Astigitanus (of Astigi – Écija), and Hispalensis (of Hispalis – Seville). Trajan, the first emperor of provincial birth, came from Baetica though he was of Italian origin. Hadrian came from a family residing in Italica while his mother Paulina was from Gades.

Seville

Located in the Maria Luisa Park and originally built as part of the 1929 exhibition, the Archaeological Museum of Seville is one of the best museums of its kind in Spain. The focus is on the Roman era, but there is also a prehistoric section which includes the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age. The galleries on the first floor are devoted to the Roman era with statues and fragments rescued from the nearby ancient site of Italica. Many mosaics are exhibited there and other highlights include sculptures of local born and raised emperors; Trajan and Hadrian.

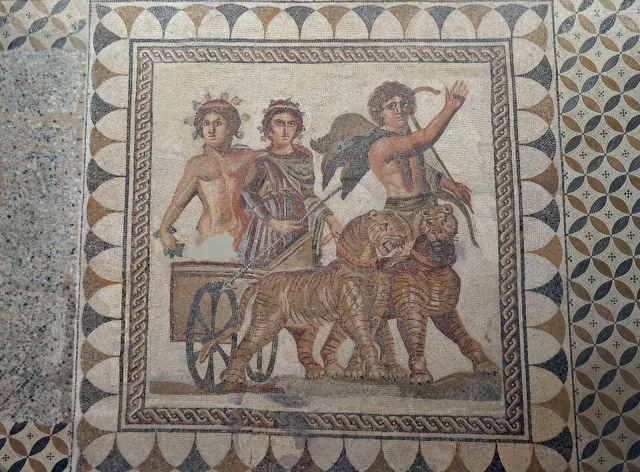

One of the most impressive mosaics housed in the museum is the opus tessellatum mosaic from Ecija depicting the mythological scene of Bacchus’s triumph over the Indies. The god is portrayed crowned with bunches of grapes in a chariot drawn by tigers. He wears a woman’s chiton covered by a nebris belted at the waist and he holds the reins with his left hand and a thyrsus in right hand. Accompanying him in the chariot is a nude figure of the young Ampelos. In front is a satyr, covered in a fawn’s skin and holding a shepherd’s crook in his left hand.

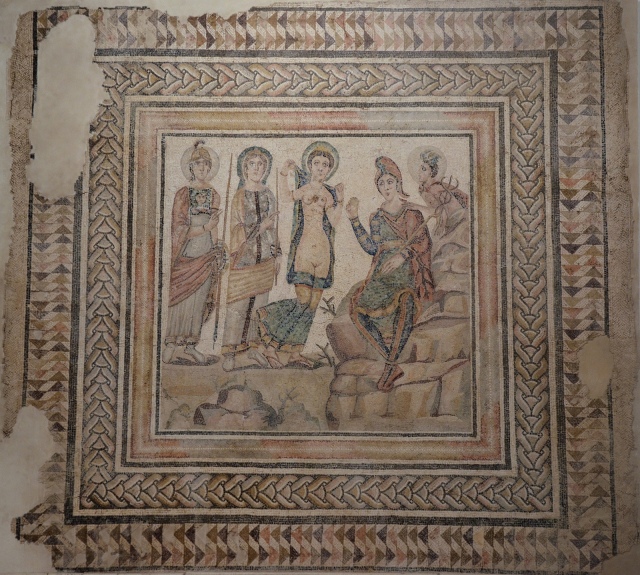

Another splendid mosaic is the figurative mosaic representing the well-known episode of the Judgement of Paris that led to the Trojan War. It was found in 1985 in a Roman villa in the town of Casariche alongside a rich series of geometric mosaics. The mosaic of the Judgement of Paris is in opus tessellatum and is dated to the 4th century AD. It decorated the atrium of the Villa del Alcaparral. The composition follows the tradition of Hellenistic pictorial motif core surrounded by geometric motifs. It depicts the moment when Paris, seated on a rock wearing a Phrygian cap and holding a pedum (a shepherd’s crook) in his hand, offers the golden apple of Venus.

In the same room as the Casariche mosaic is a mosaic fragment coming from nearby Italica. It was found in the so-called House of Hylas, named after the mosaic. Thought to date from the early 2nd century AD, the centre panel (emblema) of a larger mosaic depicts the mythological scene when Hercules’ companion and lover Hylas was kidnapped by nymphs because of his beauty while off on a mission to fetch water. Hylas, carrying a pitcher, approaches the water spring where he is trapped by the nymphs. He desperately looks towards Hercules for help who is unable to save him. The subject matter was inspired by an epic poem by Apollonius of Rhodes on the mythical expedition of the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece.

Another room in the museum (room XII) houses more figurative mosaics. The first two depict the personification of spring and autumn. Spring is represented as a young girl with flowers in her hair. Autumn is dressed as a mature woman next to a stripped tree.

On the wall next to these are two other mosaic fragments of great interest since the themes are less frequent than the previous ones. They represent one of the Romans’ favourite modes of entertainment: the races and games in the circus. Two quadrigae (Roman chariot led by a four-horse team) driven by their charioteers are represented, competing for triumph in the arena.

The last mosaic located in room XII is from Italica and is an emblema with a lion which would be inserted into a larger mosaic.

Finally, in Room XX called the “Imperial Room” for the numerous imperial portraits exhibited, another figurative mosaic is dedicated to Bacchus. The god appears in the central medallion adorned with ivy leaves. Around him are symbolic representations of the seasons, tigers with thyrsus, old bearded men and lions that lay down on the evil eye. See the full mosaic here.

Room XX with the Mosaic of Bacchus and the four seasons from Italica (101 – 225 AD) and bust of Hadrian, Archaeological Museum, Seville. Image © Carole Raddato.

Stay tuned for the next part of this series, which will explore the mosaics at the Lebrija Palace.