On a recent business trip to Zurich, I had the opportunity to tour two of the city’s great repositories of Swiss history and culture: the Museum Rietberg and the Landesmuseum Zürich (English: Swiss National Museum). Both house sumptuous works of art and special rotating exhibitions.

I arrived in Zurich after four frenetic days in Paris, feeling much relieved and relaxed. Although many deride Zurich as being “too quiet” or “too rich” — playing on “zu ruhig” and “zu reich” in German — I enjoy the city’s quiet, unassuming charms. Known primarily as a financial and business center, Zurich is also a European “cultural capital,” boasting lakeside views of the Alps, splendid churches, a gorgeous opera house, and several world class museums. I feel a sense of kinship to the city and the region as I have family ties to Canton Zurich, and I like to remind others that Zurich has been an artistic and intellectual center throughout its long history. Founded by the Romans around 15 BCE as “Turicum,” Zurich was a prosperous medieval town and later a major center for the Protestant Reformation during the sixteenth century. Fortune favored Zurich once again as it became the epicenter of Swiss industry and international finance in the nineteenth century, while radical artistic movements like Dada colored the metropolis and the rest of Europe in the twentieth century. As the largest and wealthiest city in Switzerland, there is always much to do and see here, and visiting the Museum Rietberg and the Landesmuseum were at the top of my business agenda for Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE).

Museum Rietberg

Villa Wesendonck, Museum Rietberg © Photo: Museum Rietberg

Collection of the Museum Rietberg, Southeast Asia © Photo: Museum Rietberg

After dropping my bags off at my hotel in Zurich’s picturesque Aldstadt, I took tram 7 to the Museum Rietberg, which is situated on what is arguably the city’s most beautiful green space: the Rieter-Park in Wollishofen. This museum is one of only a handful in Switzerland to focus primarily on non-western art. The museum’s collections are scattered across three 19th-century villas and a unique underground extension that was recently built between them. (The museum opened in the late nineteenth century and is thus one of Switzerland’s oldest in operation.) As I approached the museum compound, I was in awe of the beautiful views of the Zürichsee (English: Lake Zurich) and the Alps in the far distance.

Collection of the Museum Rietberg, Meiyintang © Photo: Museum Rietberg

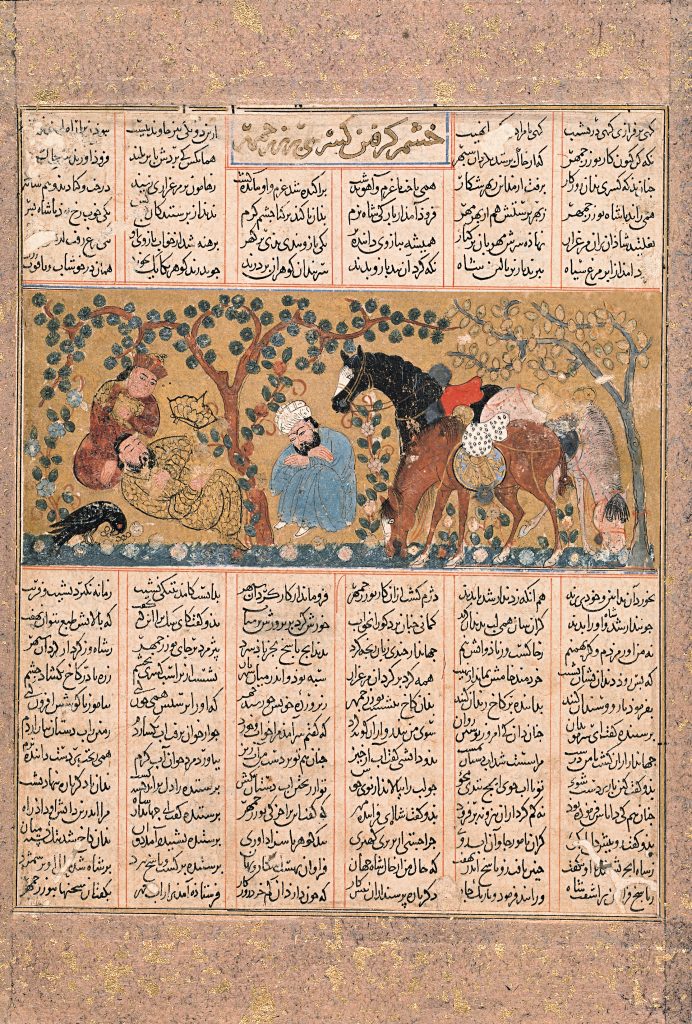

The largest of the 19th-century villas — the Villa Wesendonck — was once the temporary home of the infamous composer Richard Wagner (1813-1883) following his departure from Dresden due to the German Uprisings of 1848-1849. Today, the Villa Wesendonck houses a diverse array of ritual and religious objects from India, Oceania, the Americas, Southeast Asia, and the Near East. I can attest that the museum’s collection of early Buddhist art from South India is among the finest that I have ever seen in Europe, and the range of artifacts from the ancient Americans — with everything from the tools of a Tlingit shaman to a rare Tarascan coyote in the shape of a chair — is equally compelling. Beside the Villa Wesendonck is the the smallest edifice on the museum grounds: Park Villa Rieter. This villa displays paintings and elegant examples of calligraphy from South Asia. (The North Indian collection of miniatures is one of the best in the world, I am told by specialists.)

Collection of the Museum Rietberg, Near East © Photo: Museum Rietberg

The Museum Rietberg opened an underground extension in 2007, consisting of two subterranean floors and a visible storage space to showcase even more of their works of art. Although equipped with a handy museum map and a press packet, I felt as though I were descending into the “unknown” as I climbed the stairs down into the extension zone. Down there, I surveyed ancient, medieval, and early modern works of art from China, Japan, and sub-Saharan Africa. Enthusiasts of ancient art and history should not miss the large bronze vessels from the Chinese Zhou dynasty (c. 1500-1045 BCE), and the luxurious goods — filigree gold jewelry and wine vessels — from China’s cosmopolitan Tang dynasty (618-907 CE). My eyes came alive too as I studied the delicate medieval masks used in Japanese Noh theater and the vertical sculptures of Mali’s Dogon people. The visitor to the Museum Rietberg gets a glimpse at how museums store objects not on display in the visible storage space room. Brimming with objects from ancient Iran, China, the Americas, Africa, and Switzerland, I thought this storage space might offer some hints as to future exhibitions from the Museum Rietberg. Time will tell, but I look forward to keeping tabs on this lovely museum and I hope to visit again very soon.

Landesmuseum Zürich

The National Museum Zurich: A combination of old and new. View from Neumühlequai in January. © Roman Keller

With images of stags and does grazing under round suns and crescent moons, this heavy vessel made of pure gold depicts both heaven and earth. It was buried by a farming community as a gift to the gods in the hope that this would bring fertility to their fields and livestock. Bowl, gold. Ca. 1100 BC. Zurich-Altstetten. Canton of Zurich. © Swiss National Museum

The morning of my last day in Zurich was chaotic: I had to catch an international flight with departure time of 1:00 pm from Kloten, and I still wanted to get a sense and feel for the Landesmuseum — the Swiss National Museum — which contains the country’s largest collection of objects related to Swiss culture and history. The Landesmuseum opened in the late 1800s and retains much of that era’s grandeur in its size and exterior opulence much like the Museum Rietberg. From the outside, however, the museum resembles an expansive medieval castle. Located beside Zürich Hauptbahnhof (English: Zurich Central Station), the Landesmuseum is easily accessible from anywhere in the city center. I thought it would be a good idea to visit before catching my train to the airport.

Celtic women started wearing glass bracelets in 250 BC. Bracelets. Glass, moulded. 250 – 100 BC. Various archaeological sites. Switzerland. © Swiss National Museum

As time was limited, I opted to spend the majority of my time in the Landesmuseum’s impressive and recently opened archaeological collection, which is located on the first floor. Highlights here include a remarkable Bronze Age embossed gold bowl, countless prehistoric tools, and exquisite pieces of jewelry made by the Alemanni tribe in Late Antiquity. The “Archaeology in Switzerland” wing is split to three sections, each offering a primer on Switzerland’s rich past at the crossroads of Europe: “Terra,” “Homo,” and “Natura.” High-tech interactive tools are interspersed thoughtfully throughout the sections, and I choose to examine the finer points of ancient Celtic and Germanic ceramics given my own ancestral roots in Switzerland. Additionally, I took note that many recent discoveries made by Swiss archaeologists are exhibited along side artifacts uncovered in the past two centuries, rendering a thought-provoking juxtaposition. How neat it was to see the evolution of human settlement and archaeology as a discipline in Switzerland! With over 500 objects on display here alone, there is a great deal to see and something for everyone.

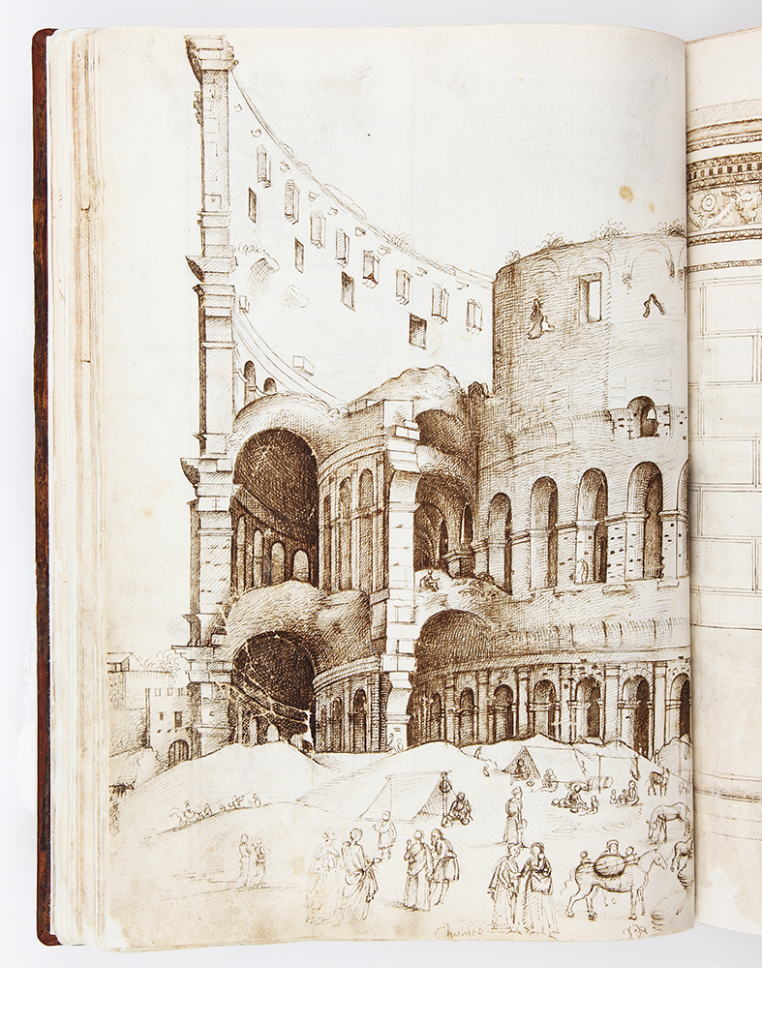

Attributed to Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494), Codex Escurialensis, Italy, ca. 1491. © PATRIMONIO NACIONAL, Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, inv. no. 28-II-12.

Before leaving the Landesmuseum, I made a point to walk through Europe in the Renaissance: Metamorphoses 1400-1600 exhibition. While I am proud as the co-founder of Ancient History Encyclopedia, I am not a classicist by background or training. (World history and Middle Eastern/Islamic Studies are my areas of expertise.) The European Renaissance is my favorite era in history by virtue of its enduring artistic and intellectual legacy in the West. This magnificent exhibition traced the important advances made in this era — everything from Gutenberg’s printing press and the Columbian exchanges to the revolutions in the arts and sciences. The show featured a dazzling array of art and treasures from major European museums, which demonstrated how the Renaissance was an intra-European movement. This focus and perspective distinguished Europe in the Renaissance from other recent, large scale exhibitions covering the same era like France 1500 or Elizabeth and Her People. Nonetheless, I was glad that the curators had illuminated Switzerland’s unique role and contribution to the Renaissance with the presentation of Swiss woodcuts, drawings, and religious artwork. The exhibition catalogue is already a firm, personal favorite.

This helmet found in a grave in Ticino belonged to a mercenary soldier from the central Alps who was serving in the Roman imperial army. Negau helmet, bronze. 150 – 50 BC. Giubiasco. Canton of Ticino. © Swiss National Museum

Both museums are well worth a visit and accessible thanks to Zurich’s efficient public transportation system. The Museum Reitberg is one of the more unusual museums that I have ever toured, and I shall hopefully have more time to explore the vastness of the Landesmuseum when I return in March 2017.

Cover image: View of Zürich’s Altstadt from Münsterbrücke, facing the Zürichsee. Taken by James Blake Wiener on 19 November 2016. © Ancient History Encyclopedia 2017.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to AHE by the Museum Rietberg and the Landesmuseum Zürich have been done so as a courtesy, and we thank them warmly for their generosity. Thanks must be given to Mr. Alain Suter, Deputy Head of Communication and Cooperation, Media Relations at the Museum Rietberg and Mr. Alexander Rechsteiner, Public Relations Officer at the Landesmuseum Zürich. Additional gratitude is given to Ms. Brigit Kull and Mr. Attila Albert. This piece was edited by James Blake Wiener for AHE. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2017. Please contact us for rights to republication.