Last month, I had the chance to visit a hidden gem among Madrid’s better-known museums: Museo de América (English: Museum of the Americas). Filled with thousands of pre-Columbian artifacts, treasures, and works of art, the Museo de América explores the languages, religions, and cultures of the Americas — from the Arctic Circle to Tierra del Fuego — as well as their interactions with imperial Spain.

Conquest of Mexico — The Reception of Emperor Montezuma. Authors: Miguel González and Juan González. Date: 1698 CE. Cultural Context: Vice royalty of New Spain/Mexican School. Provenance: Mexico (North America). Material: Canvas, oil painting, nacre. Technique: Enconchado. Dimensions: Height = 97 cm; Width = 53 cm. Nº Inventario: 00110.

Madrid is an enjoyable kaleidoscope into Spain’s rich cultural patrimony. Founded in 1561 CE, the Spanish capital is among Europe’s youngest but also most interesting cities. While Barcelona receives rave reviews from travelers and business professionals alike, many forget that Madrid too pulsates with activity, gastronomical adventures, and the performing arts. It has also world-renown museums like the Prado, the Museo del Arte Thyssen-Bornemisza, and the Museo Nacional Centro del Arte Reina Sofía. After having absorbed the overpowering Rocco grandeur of the Palacio Real and touring the spectacular Museo Arqueológico Nacional, I visited the Museo de América upon the recommendation of Mr. James Doyle, Assistant Curator for the Art of the Americas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, New York. I have long been interested in colonial Latin American history and the various Pre-Columbian civilizations of the ancient Americas, so I knew that I was headed to the right place.

Kero in the form of a jaguar’s head. Date: 1501-1600 CE. Cultural Context: Inca-colonial style. Provenance: Department of Cuzco (Peru, South America). Material: Wood, pigment, resin. Technique: Carving, chiseled, painted, varnished. Dimensions: Height = 22 cm; Base: Maximum Diameter = 14,50 cm. Nº Inventario: 07508.

On a rainy Saturday morning, I made my way from Moncloa metro station to the Museo de América, which is located in northwestern Madrid. Upon arrival at the museum, I met Dr. Ana Azor Lacasta (Assistant Director) and Dr. Andrés Gutiérrez Usillos (Chief of the Pre-Columbian Department) who would show me around the collections. Before exploring the museum, Ana and Andrés provided some useful background on the museum and its holdings. The Museo de América opened in 1965, and the items that comprise the museum’s contents came from collections originally scattered all over the Spain. The highlights — not surprisingly — are those objects and pieces d’art sent from the Americas to the Habsburg and Bourbon monarchs who governed Spain over the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Other fine archaeological and ethnographic specimens came to Spain as a result of later expeditions undertaken by researchers like Antonio del Río, who explored the Mayan city of Palenque in Mexico, and Alejandro Malaspina, who led a scientific expedition to South America and then Oceania.

Helmet. Date: 1775-1800 CE. Cultural Context: Tlingit Style (Northwestern coast). Provenance: Alaska (United States). Material: Wood, shell, leather, copper and pigments. Technique: Carving, painted, perforated, cast, embedded. Dimensions: Height = 28,50 cm; Width = 27 cm. Nº Inventario: 13909.

Although the museum’s artifacts are separated by two floors and countless rooms, objects are thoughtfully arranged into specific collections based on an underlying or unifying theme. Ana, Andrés, and I began our tour on the first floor, continuing onward to the second. The duration of my visit would last a little over two hours. The collection I found most intriguing on the first floor was “The Reality of America.” When the Spanish first arrived in the New World, they encountered complex civilizations in Mesoamerica and the Andes each with their own artistic traditions and diverse religious beliefs. Wherever they went or with whomever they encountered, the Spanish mythologized much of what they saw, leaving us with fantastical sketches of mythical beasts, and idealized scenes of conquest and power with classical allusions. Through a process of conquest, political consolidation, and acculturation, a new “Iberoamerican” society and consciousness emerged throughout much of the Americas. It is worth noting that discernible artistic and cultural influences also arrived in colonial Spanish holdings from East Asia due to the annual passage of the Manila galleons that traversed the Pacific Ocean from Manila to Acapulco. Biombos or delicate folded screens thus recall the sophisticated filigree of Japan and China, and were prized by elites throughout the Spanish Empire.

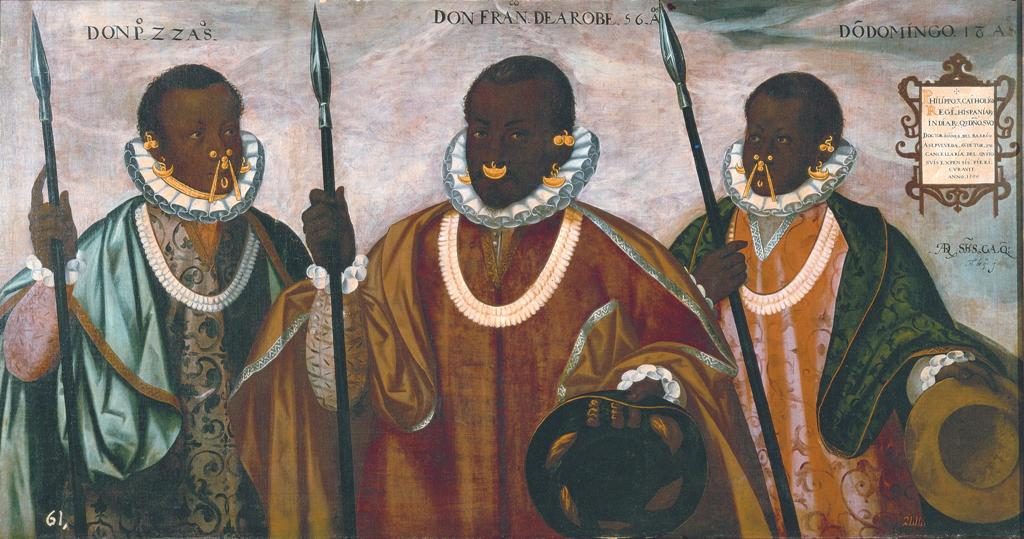

I personally found the symbolic images of this new society to be both arresting and thought-provoking. The infamous casta paintings — due their emphasis on cross-breeding and ethnic variance — attest to the collision and eventual merger of the three dominant cultures across Spain’s holdings in the western hemisphere: Native American, Spanish, and African. Over time, the Spanish traded widely, penetrating deeply into the interior of what is now the United States, and they even attempted to settle the Pacific Northwest coast of present-day Canada. Ana and Andrés told me about the Spanish forts of Santa Cruz de Nuca and San Miguel, which lasted from 1789-1795 CE, and I was delighted when they pointed out several Tlingit and even ancient Hawaiian artifacts on display throughout the first floor.

A casta painting of a Spaniard married to a mestizo lady and their castiza daughter. Author: Miguel Cabrera. Date: 1763 CE. Cultural Context/Stye in the Mexican School. Provenance: Mexico (North America). Technique: Oil on canvas. Dimensions: Height = 132 cm; Width = 101 cm. Nº Inventario: 00006.

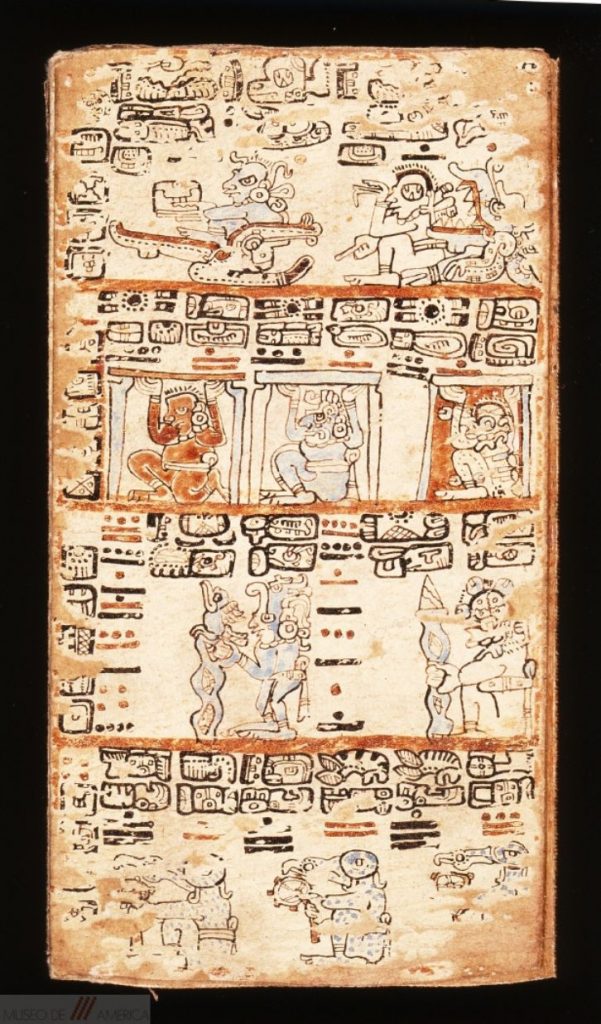

Madrid Codex. Date: 15th century CE. Cultural Context: Maya Postclassic Style. Provenance: Yucatán, Mexico (North America). Material: Amate paper and natural pigments. Technique: Painted. Dimensions: Height = 22,6 cm; Length = 416,5 + 238,5 cm. Nº Inventario: 70300.

As we proceeded into to the collection entitled “Bands and Society,” my eyes were greeted by an exceptional array of artifacts from a huge geographical range: Alaska to Brazil, Patagonia to Puerto Rico. Among the masterpieces here are Totonac sculptures from Mexico, exquisite vegetable trays created by the Chumash people of coastal California, and anthropomorphic figurines made from wood by the Chimú culture of Peru. Every artifact exhibited in this section of the Museo de América underscored the importance of social organization as reflected in indigenous art and ritual. Many artifacts also alluded to complicated kinship networks and rigid social hierarchies. I thought some of the Taíno pieces in the museum’s possession best delineated the complexities of indigenous society before the arrival of the Spanish in 1492 CE.

Due to Spain’s prolonged economic crisis in recent years, very few visitors have the opportunity to visit the second floor of the museum. This is a shame as the artifacts showcased here are among the museum’s real gems: The Madrid Codex (also known as the Trocortesiano Codex or the “Troano Codex”), which is one of only four surviving pre-Columbian Maya books dating to the Postclassic Era (c. 900–1521 CE); the so-called “Treasure of Quimbaya” from present-day Colombia, which discovered in 1893; a complete ancient mummy from Paracas in Peru; and an exquisite colonial painting of Potosí from 18th-century Bolivia. On this floor, the Museo de América compares and contrasts Spanish political power, Catholicism, and modes of communication with those from pre-Hispanic societies in the ancient Americas.

There is a special section on the second floor entitled “Communication” where visitors can discover animal hides with pictograms created by the Woodland Indians of North America, vessels and panels with Mayan glyphs, landscape paintings of Seville at the height of the Spanish Golden Age in the sixteenth century, and a handsome portrait of the literary genius Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695 CE). This was my favorite part of the museum because of my background as a writer and as a researcher. The visitor should not miss the Madrid Codex, in particular, due to its importance in our understanding of ancient Mayan culture. The codex illuminates sacred rituals like sacrifice and the invocation of rain, while simultaneously depicting activities like weaving, cleaning, hunting, and even beekeeping.

The Mulattos of Esmeraldas. Author: Andrés Sánchez Gallque. Date: 1599 CE. Cultural Context: Vice royalty of Peru/School of Quito. Provenance: Quito (Pichincha Provence), Ecuador. Material: Canvas, oil painting. Technique: Oil on canvas. Dimensions: Height = 92 cm; Width = 175 cm. Nº Inventario: 00069.

Upon leaving the Museo de América, I felt gratified having seen such splendid artifacts and works of art from my own hemisphere. Nearly every corner contained something astonishing, whether small or large in size. Although this worthwhile museum is not nearly as well known as the world’s other fine museums of Pre-Columbian art in Latin America or the United States, this museum offers new perspectives on cross-cultural interaction on a monumental scale that should not be missed when one visits Madrid. I, for one, cannot wait to go back to visit again!

Mummy and bundle from the Paracas culture of Peru. Date: 100-200 CE. Cultural Context: Paracas style. Provenance: Wari Kayan, Cerro Colorado, Paracas (Peru, South America). Material: Organic material support; Basket: Vegetable fiber; Fabric: Fiber of camelid, cotton. Technique: Fabric, plain cloth 1×1, embroidery. Dimensions: Height = 75 cm; Maximum diameter = 95 cm. Nº Inventario 70311.

Cover image: Façade of the Museo de América in Madrid, Spain. CC BY-SA 3.0. Created by Luis García on 25 February 2011.

Be sure to explore the Museo de América’s rich collection by accessing their online catalog search tool.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to AHE by the Museo de América have been done so as a courtesy, and we thank them warmly for their generosity. Immense gratitude is extended to Dr. Ana Azor Lacasta and Dr. Andrés Gutiérrez Usillos for helping facilitate this piece and accompanying Mr. James Blake Wiener on his tour. This piece was edited by James Blake Wiener for AHE. Translation from Spanish to English was undertaken by James Blake Wiener. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2017. Please contact us for rights to republication.