This is a cross-posting from the blog Gates of Nineveh. Part 1 and Part 2 of the original posts can be found there.

Last week ISIS released yet another propaganda video, showing what has been feared since the fall of Mosul last summer: the destruction of ancient artifacts of the Mosul Museum. By now most of the world has seen this video, which has been featured in all the world’s major news agencies. This post will attempt to identify what has been lost and assess the damage.

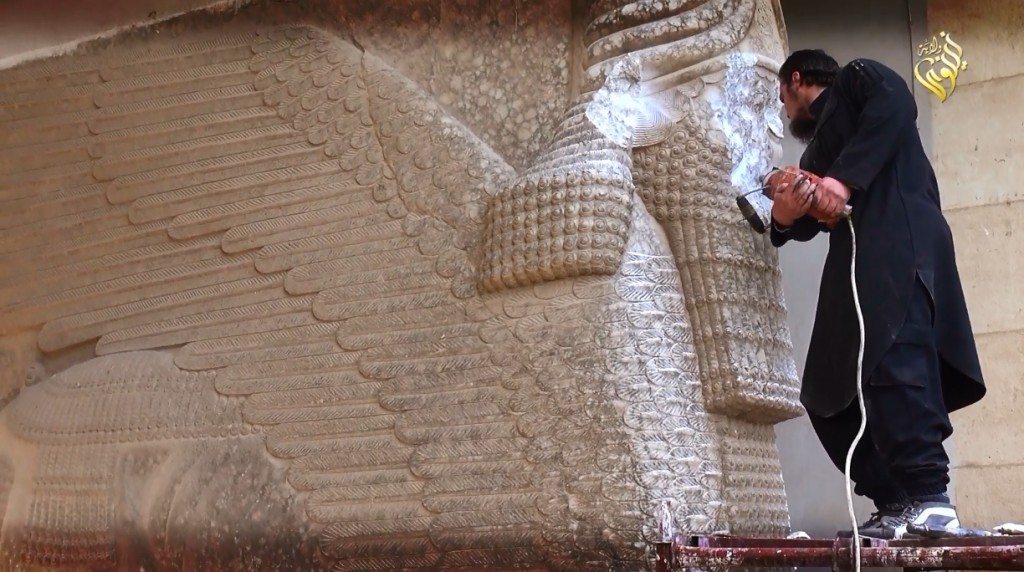

Narrator stands in front of a lamassu in an ISIS propaganda video.

As in several of the group’s past videos, a spokesman for the group appears in the video to explain the rationale for the destruction. International Business Times has provided a translation:

These ruins that are behind me, they are idols and statues that people in the past used to worship instead of Allah. The so-called Assyrians and Akkadians and others looked to gods for war, agriculture and rain to whom they offered sacrifices…The Prophet Mohammed took down idols with his bare hands when he went into Mecca. We were ordered by our prophet to take down idols and destroy them, and the companions of the prophet did this after this time, when they conquered countries.

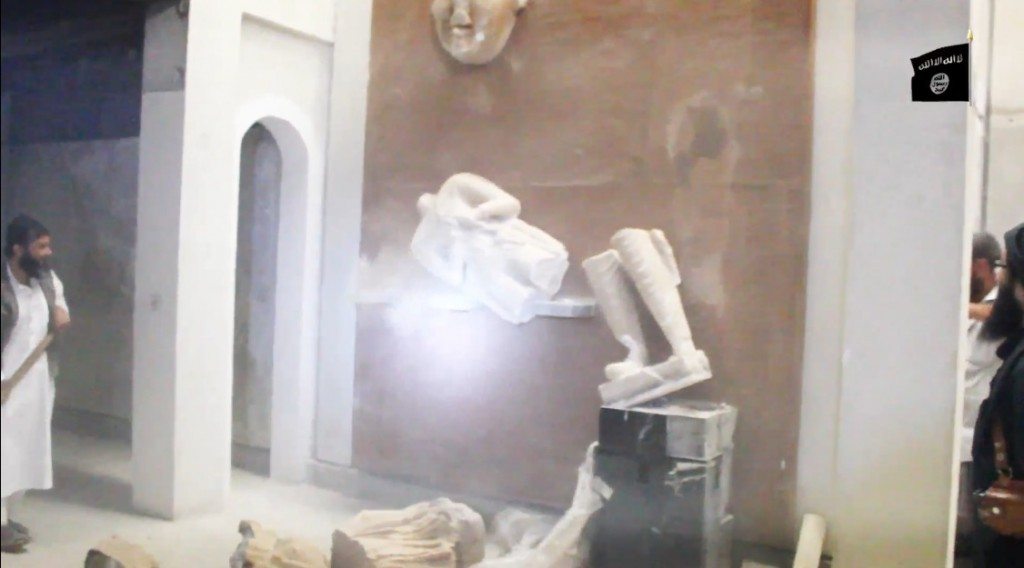

The video then shows a montage of ISIS fighters toppling sculptures, smashing them with sledgehammers and using jackhammers to pulverize the faces of some statues.

Most of the destroyed artifacts fall into two categories: Sculptures from the Roman period city of Hatra, situated in the desert to the south of Mosul, and Assyrian artifacts from Nineveh and surrounding sites such as Khorsabad and Balawat.

In some ways, it could have been worse. In 2003 around 1,500 smaller objects from the Mosul Museum were relocated to the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad in order that they may be better protected. Nevertheless, many statues otherwise too large or delicate to be moved remained.

The Nergal Gate

The scene with the narrator was shot at the Nergal Gate, one of the gates on the north side of Nineveh. The entrance to the gate was flanked by two large winged human-headed bulls known as lamassu in Akkadian. The gate and its lamassu were first excavated by Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1849 but then re-buried. The left lamassu (seen above behind the ISIS narrator) was uncovered again sometime before 1892, and a local man paid an Ottoman official for the top half of it, cut it off and broken down over a fire in order to extract lime. The right lamassu remained buried until 1941 when heavy rains eroded the soil around the gate and exposed the two statues. The gate was later reconstructed around them and they have remained on display ever since.[1]

The gate was built during Sennacherib’s expansion of Nineveh sometime between 704 and 690 BC.

The video stops at 2:26 to highlight the sign which states that “this gate is related to the god Nergal, the god of plague and the lower world.” The left lamassu, already missing its upper half, does not seem to have been targeted. The right lamassu had its face chiseled off with a jackhammer, likely causing irreparable damage.

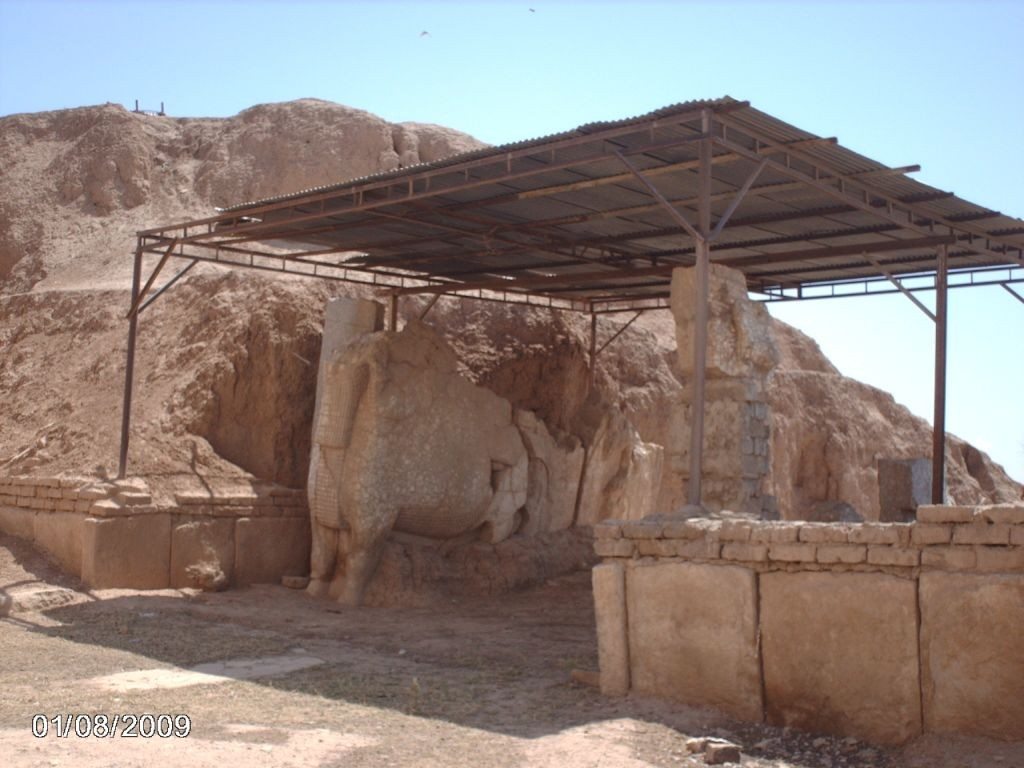

There is no indication that the reconstructed gate itself was damaged. Inside the gate there are two additional lamassu which were less well preserved than the lamassu on the outside of the gate. Both were heavily cracked, and the one on the left was missing his head above the nose and the one on the right was missing everything except its head.

There is no indication that the reconstructed gate itself was damaged. Inside the gate there are two additional lamassu which were less well preserved than the lamassu on the outside of the gate. Both were heavily cracked, and the one on the left was missing his head above the nose and the one on the right was missing everything except its head.

The lamassu on the left was broken apart with sledgehammers into large chunks. The head on the right was broken apart with a jackhammer.

Interior of the Nergal Gate in 2009. (Source)

Other lamassu

At 1:10 of the video, two additional lamassu can be seen. These are an earlier type from Nimrud with a lion’s body instead of a bull’s. They are not shown being destroyed although by the end of the video all immovable sculptures in the museum seem to have been destroyed so there is little hope for their survival.

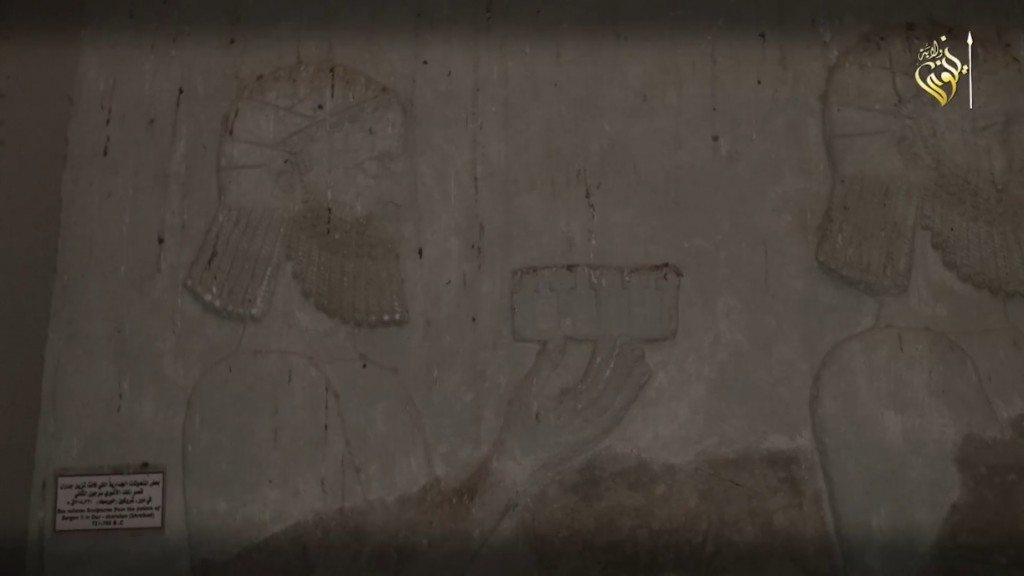

Assyrian Relief Sculptures

At 1:19 a partially reconstructed relief identified by its sign as coming from Dur-Sharrukin (modern Khorsabad) can be seen. The city was constructed by Sargon II sometime after 716 BC and abandoned upon his death in 705. This sort of relief usually shows tribute-bearers seeking an audience with the king and in this case one of the supplicants is holding a model of a fortification.

Relief from Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad) in the Mosul Museum, 1:19 of ISIS video.

Palace relief from Dur-Sharrukin (Khorsabad) in the Mosul Museum. Photo (c) Hubert Debbasch.

Four other reliefs shown in the video appear to be replicas of rock reliefs in Kurdistan or originals held in the British Museum.

Statue of Sargon (?)

At the 1:44 mark the video showed a fallen, broken statue identified by a museum sign as a statue of Sargon II of Assyria (r. 722-705 BC):

This statue appears to be at least partly made of plaster. It may be a partial reconstruction based on an original base. Similar statues of the god Nabu were found at Dur-Sharrukin. It is not, however, a statue of Sargon II but merely one from his reign:

Statue from the Temple of Nabu in Dur-Sharrukin. From the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. Photo by Author.

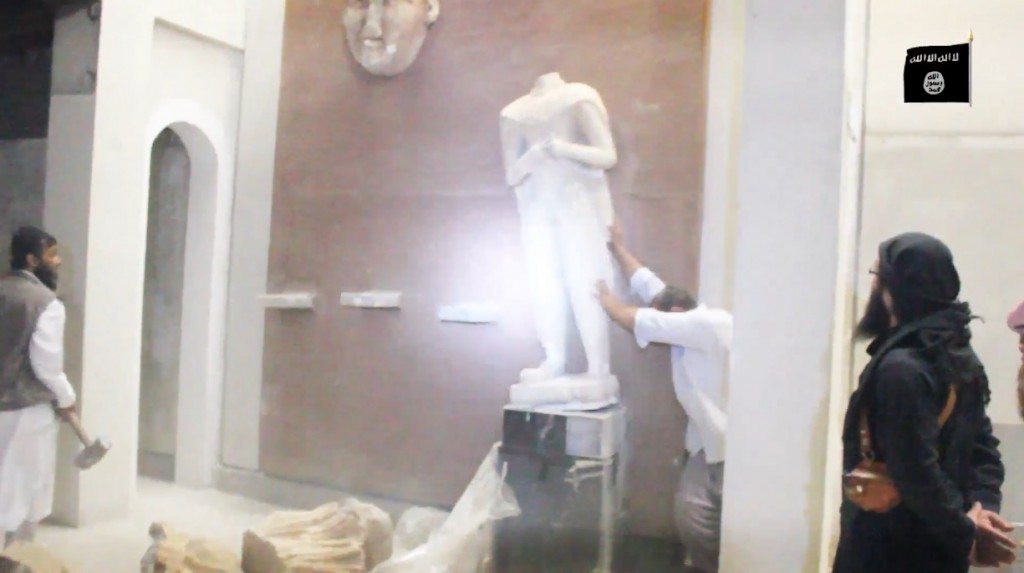

Statues of the Kings of Hatra

Hatra was a wealthy trading city located in the desert south of Mosul, one of several such cities which sprung up in the space between Parthia and the Roman Empire. Hatra, Palmyra, Petra and Dura-Europos all made their fortune as intermediaries, trading stops between east and west. All of these cities were client states of either Rome or Parthia, with Hatra choosing Parthia.

This made Hatra a target for Rome, and Trajan besieged the city during his Mesopotamian campaign in 114 AD but failed to capture it. Septimius Severus launched several assaults on the city during his invasion of Parthia in 198 which also failed. The heat, the open plain which made it difficult to approach the walls undetected, and the lack of any water or food in the area around the city kept Hatra safe from protracted sieges. Hatra was destroyed in 240, not to Rome but to the forces of the Sassanid monarch Shapur I during his campaign against the last Parthian client states that stood between himself and renewed war with the Roman Empire.

Hatra’s unique position between east and west produced an outpouring of art unique in the Parthian empire. Influences from east and west mixed to create a very naturalistic but still unmistakably eastern artistic style. Here gorgon heads adorned temples to Near Eastern gods alongside Aramaic inscriptions. Mesopotamian deities such as Shamash and Nergal were depicted alongside Greco-Roman deities such as Hercules. Classical nudes and statues adorned in ornate Parthian robes existed side by side. One statue of Apollo the Roman sun god even featured symbols of Shamash the Near Eastern sun god on his clothing.

The damage by ISIS to the artistic legacy of Hatra has been catastrophic.

The beginning of the video (0:08) shows three men hitting two statues with a sledgehammer while failing to do much damage. They try to pull the statues over without success.

The beginning of the video (0:08) shows three men hitting two statues with a sledgehammer while failing to do much damage. They try to pull the statues over without success.

These statues represent kings of Hatra. The statue on the left is of an unidentified king of Hatra, dressed in a Parthian style and holding an acanthus leaf in his left hand and a piece of fruit in his right. Its museum number is MM5.

The statue on the right has been called “the finest of all the sculptures unearthed in Hatra.” An Aramaic inscription on the base of the statue reads “The Image of King Uthal, the merciful, noble-minded servant of God, blessed by God.” All other details about this king’s life, including the dates of his reign, remain obscure.[2]

At the 2:50 mark the statue of Uthal is shown being snapped at the base and toppled. Three men attack the statue with sledgehammers after it hits the ground. Both statues are seen broken into numerous pieces on the floor.

At 2:53 a third statue can be seen being toppled. This is a statue of Sanatruq II, the last king of Parthia before the city was destroyed by Shapur I in 240.[3]

This statue was reconstructed from several fragments, so it shattered easily when it hit the floor.

Another sculpture is seen being unwrapped at 0:38. This is a depiction of an unidentified Hatrene king holding an eagle symbolizing the ancient near eastern sun god Shamash.

The statue was toppled but it took a number of blows with a sledgehammer to dismember it.

We have 27 known statues of kings of Hatra, so the destruction of four of them represents a loss of 15% of all statues of Hatrene kings in existence.[4]

Other Large Hatrene Sculptures

The sculpture on the right is a statue of a Hatrene nobleman dressed in the Parthian style. This is one of the earlier Hatrene sculptures found and dates to the 1st century AD. Its catalog number is MM14.

The sculpture on the right is a statue of a Hatrene nobleman dressed in the Parthian style. This is one of the earlier Hatrene sculptures found and dates to the 1st century AD. Its catalog number is MM14.

The statue on the left is believed to be of a priest based on its clothing. It was missing its head when excavated.[5]

Statues seen at 0:40 and 2:43 of the video. From Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 19, pl. 199, pp. 75, 212.

In another alcove at 3:16 a headless statue can be seen, clutching a sword in his hands and wearing long pleated trousers and a cape. An inscription identifies it as a depiction of a certain Makai ben Nashri.[6] This statue was toppled sideways off its base and snaps in half when it hits an architectural element along the wall. When it hits the floor the legs break into several more pieces.

Statue of Makai ben Nashri seen in 3:16 of video. Left photo by Diane Siebrandt, U.S. State Department, 2008. Right photo from Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, p. 78.

Greco-Roman Influenced Sculpture

A headless statue of Hercules is seen being toppled. However, when it hits the ground it shatters into hundreds of pieces, revealing it to be a plaster cast with steel rebar inside. The original is kept in the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad.

Near the beginning of the video an ISIS fighter is shown unwrapping a nude female torso, believed to be a depiction of Venus/Aphrodite.[7] The camera cuts away before the statue is unwrapped and the sculpture is not seen again, however, it may be one of the broken objects in the background of the shot of the Hercules statue shown above at 3:59.

Near the beginning of the video an ISIS fighter is shown unwrapping a nude female torso, believed to be a depiction of Venus/Aphrodite.[7] The camera cuts away before the statue is unwrapped and the sculpture is not seen again, however, it may be one of the broken objects in the background of the shot of the Hercules statue shown above at 3:59.

Venus statue. Photo by Dr. Suzanne Bott, 2009.

Another statue shown smashed on the floor is one of many small statues of Nike uncovered at Hatra, not all of which have been published:

Statue of Nike, Greek goddess of victory. Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 102 p. 125. This specific statue is kept in Baghdad.

Other Hatrene Sculptures

A statue of a seated goddess holding a sphere and a large mask-type sculpture of a face are both seen being shattered, however both appear to be replicas. The original of the seated goddess is kept in Baghdad and the mask is a cast of an architectural element from Hatra.

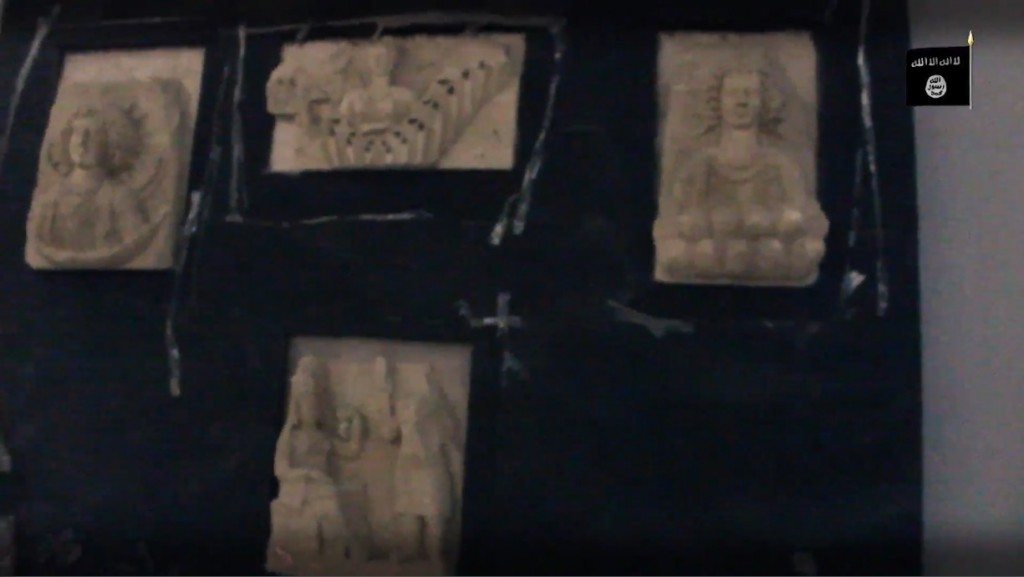

Early in the video one shot shows a number of plaques depicting Hatrene gods and goddesses:

From left to right: Barmaren, Marten, Maren. From Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 88, 89, 90, p. 113-115.

Clockwise from far right: Maren, Marten receiving a worshiper, the moon god Barmaren, Marten again.[8]

A large eagle is seen being toppled over and shattered. This eagle was once also an architectural element from Hatra. It was partially reconstructed.

A large eagle is seen being toppled over and shattered. This eagle was once also an architectural element from Hatra. It was partially reconstructed.

Mosul Museum eagle prior to reconstruction. From Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 133, p. 143.

Three small reliefs are shown being destroyed at 3:46. All are pulverized with sledgehammers and ripped out of the wall. All are from Hatra, the middle published by Safar and Mustafa, the right unpublished and the left is too blurry to be identified in the video but other pictures from inside the museum make it clear that it is a relief of a reclining woman.

Relief sculpture of a military figure. From Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 92, p. 116.

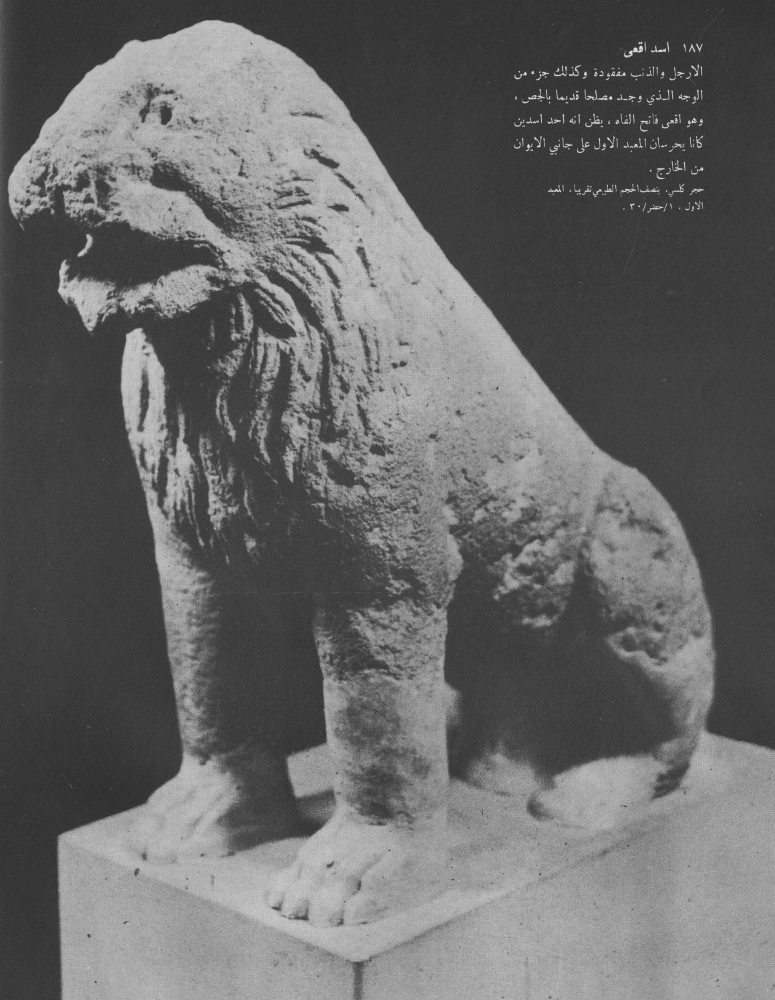

In the background at the 0:32 mark a statue of a lion can be seen. Its final disposition is not seen in the video but it is likely one of the blurry piles of rubble seen towards the end:

Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 187, p. 198.

It is important to note that there are many more items from the Mosul Museum which were not shown in ISIS’ video. The Islamic art wing was not shown at all, and most of the Assyrian section does not appear in the video either. This does not mean that these artifacts have survived. Their destruction may have been cut from the video before release. Alternately, such items may have been smuggled out and sold on the antiquities market or may still be in the museum.

Regardless, from what we can see in this video the loss for the study the Roman and Parthian Near East is absolutely devastating.

Special thanks to Dr. Suzanne Bott for uploading many pre-destruction pictures of the Mosul Museum, Hubert Debbasch for providing photos from his travels, to Dr. Lamia al-Gailani Werr for information about replicas in the museum, and to Dr. Lucinda Dirven for more information about museum replicas and bibliographic information.

References

[1] J.P.G. Finch, “The Winged Bulls at the Nergal Gate of Nineveh,” Iraq 10, No. 1 (Spring 1948): 9-18.

[2] Shinji Fukai, “The Artifacts of Hatra and Parthian Art,” East and West 11, No. 2/3 (June-September 1960): 142-144, pl. 2-3; Fu’ad Safar and Ali Muhammad Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God [Arabic title al-Ḥaḍr, madīnat al-shams] (Baghdad: Wizarat al-Iʻlām, Mudīrīyat al-Athār al-ʻĀmmah, 1974), 197-198, pl. 208-210.

[3] Fukai, “The Artifacts of Hatra and Parthian Art,” 144 pl. 4; Henri Stierlin, Cités du Désert: Pétra, Palmyre, Hatra (Fribourg: Seuil, 1987), 198, pl. 178; Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, 23, pl. 4.

[4] Michael Sommer, Hatra: Geschichte und Kultur einer Karawanenstadt im römisch-parthischen Mesopotamien

(Mainz: Zabern, 2003), 75, pl. 106; Lucinda Dirven, “Aspects of Hatrene Religion: A Note on the Statues of Kings and Nobles from Hatra,” 209-246 in The Variety of Local Religious Life in the Near East in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2008), 220-221.

[5] Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, 75, 212, pl. 187, 199.

[6] Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 24, p. 78.

[7] Safar and Mustafa, Hatra: The City of the Sun God, pl. 84, p. 110.

Article © Christopher Jones 2015. Republished with permission of the author.