Life is Short, Art Long: The Art of Healing in Byzantium, at the Pera Museum (Pera Müzesi) in Istanbul Turkey, offers visitors a glimpse of Byzantine culture and society through the three traditional methods of healing practiced side-by-side: faith, magic, and medicine. Health has always been a chief concern of humanity, and this landmark show examines Byzantine civilization from the perspective of its approach to the body, in sickness and in health.

In this exclusive English language interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Dr. Brigitte Pitarakis, curator of the exhibition, about the ways in which Byzantines understood medicine, health, and healing from ancient Roman times until the fall of Constantinople in 1453 CE.

JW: Dr. Brigitte Pitarakis, it is an immense pleasure to speak to you on behalf of Ancient History Encyclopedia! This interview marks the first time that we have worked with a curator associated with a cultural institution in Turkey. Merhaba!

Entrance to “Art is long, Life is Short” at the Pera Museum in Istanbul, Turkey. (Courtesy: Pera Museum/Pera Müzesi.)

The topic of health in the Byzantine Empire is a unique prism through which one can analyze Byzantine history, culture, and identity. Why did the Pera Museum choose to explore this subject? Additionally, I am curious to know if medicine in the ancient and medieval world is an interest of your own.

BP: Despite the tremendous progress of scientific research, we are surrounded by a growing number of people affected by emotional and physical pain. There is also growing interest in various forms of body care (spas and massages), natural foods, and therapy. These are two closely related aspects of a universal phenomenon that seems to have parallels in earlier societies. Byzantium is an interesting example because of its place at the intersection between antiquity and the Renaissance, as well as between East and West. The multifaceted behavior of the Byzantines toward illness and wellness lies at the root of our own behavior today.

As an adviser to the Byzantine section of the Istanbul Research Institute of the Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation, I had previously organized two Byzantine exhibitions at the Pera Museum — one on the Chora Monastery (Kariye Cami) in 2007, in collaboration with Robert Ousterhout and Holger A. Klein, and a second one in 2010 on the Hippodrome of Constantinople, in collaboration with Jonathan Bardill and A. Tayfun Öner. On the occasion of a public talk at the Istanbul Research Institute in the winter of 2010, I had presented preliminary observations on my new research on Byzantine amulets and the specialized vocabulary intended to ward off evil. This research led me to explore the shifting frontiers between religion, magic, and medicine in Byzantium and brought to my attention the power of the ancient heritage from the cultures of the Mediterranean in the formation of popular beliefs in Byzantium.

The strong separation of medicine and science from the categories of religion, superstition, and magic seems to have grown out of the Western Enlightenment of the 18th century CE. In Byzantium, the frontiers between these categories were not clearly delineated, and people in search of healing alternatively went to physicians, hospitals, holy men, healing sanctuaries, and magicians. Faith and superstition were strongly anchored features of Byzantine civilization, and the Byzantines switched from one healing method to another in a very natural and spontaneous way.

For the tenth anniversary of the founding of the Pera Museum by the Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation, I thought that an exhibition on the art of healing in Byzantium would be an attractive and challenging project through which we could offer not only innovative insight into Byzantium, but also bring the Byzantines closer to the concerns of today’s world. One of the co-founders of the Pera Museum, Mrs. Suna Kıraç, was diagnosed with ALS [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis] in 2000, and she can only communicate with her eyes. Since 2007, the Pera Museum auditorium has hosted the Suna Kıraç conferences on neurodegeneration, organized by the Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation in collaboration with Boğaziçi University. The Suna and Inan Kırac Foundation focuses on education, culture, and the arts. Health also features as a central theme among its activities and goals.

My personal interest in medicine in the ancient and medieval worlds stems from my exploration of the supernatural methods the Byzantines used for fighting disease. “Religion and Reason” is one of the three themes of the scientific program Labex Resmed (Laboratoire d’Excellence Religions et Sociétés dans le Monde Méditerranéen), launched by my Research Center (UMR 8167 Orient et Méditerranée), which also includes a department specializing in Greek medicine. Labex Resmed kindly sponsored the 3D animation “The Wondrous Waters of Constantinople,” a central work of the exhibition, offering a virtual reconstruction of Byzantine Constantinople from the perspective of the distribution and uses of water in the city.

During the preparation of the exhibition, I called upon the expertise of several colleagues in Paris and abroad specializing in the history of medicine. The twelve essays in the exhibition catalogue are intended to complement and complete the information provided in the exhibition itself. In addition to the catalogue, scientific background on the exhibition has included a symposium that took place on March 14, 2015, which is the “Day of Medicine” in Turkey.

JW: Daily rituals in Byzantium involved the maintenance of well-being, the protection against malevolent forces, and the purification the body and soul. Healing — especially divine healing — also fascinated Byzantines over the centuries.

Dr. Pitarakis, could tell us more about the “art of healing,” and how physicians and the general populace practiced good health in the Byzantine Empire?

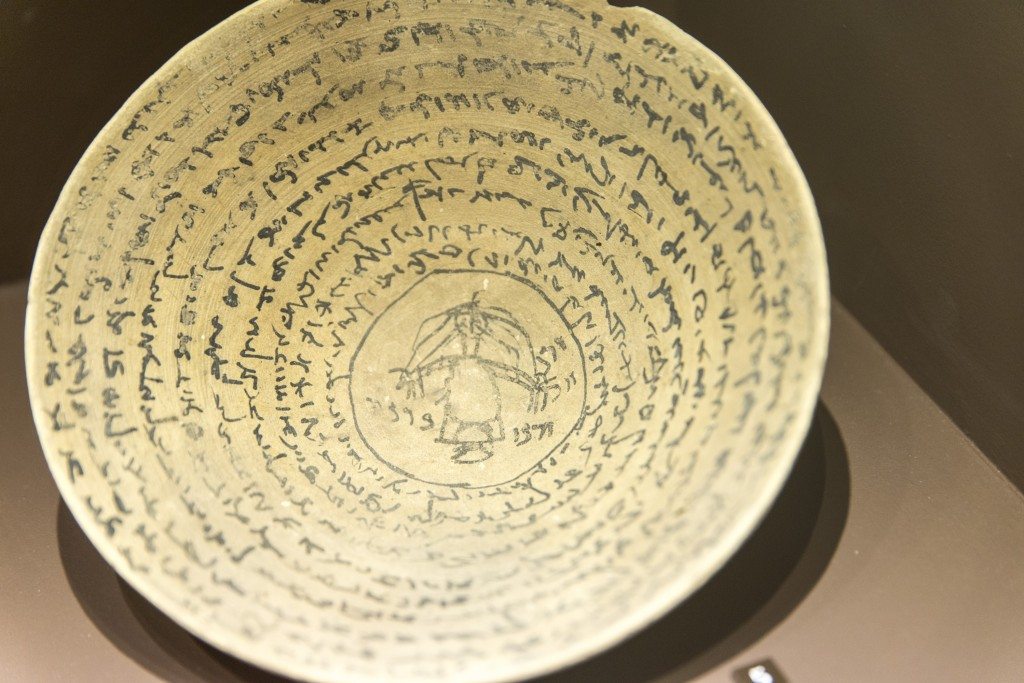

One of the many objects on display at the Pera Museum’s “Life is short, Art is long.” (Courtesy: Pera Museum/Pera Müzesi.)

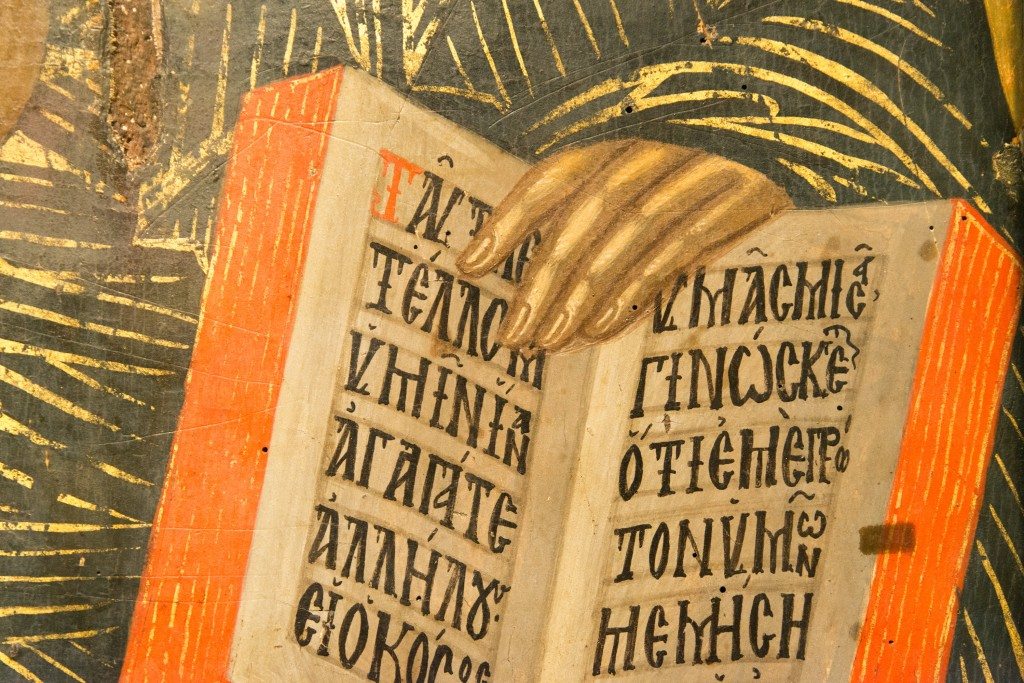

BP: The father of medicine, Hippocrates (c. 460-c. 377 BCE), characterized the substance of medicine as an art (techne), with distinct limits requiring particular skills and specialized training. Hippocratic medicine offered a rational approach to disease and placed the incurable beyond the boundaries of medical art. Our title, “Life Is Short, Art Long,” was borrowed from the first aphorism of Hippocrates inscribed in the book that he holds on the famous portrait on the frontispiece of the 14th-century CE manuscript from the Bibliothèque nationale de France. (Ms Grec. 2144). In my opinion, it is one of the masterpieces in the exhibition. This sentence served as a motto for the structure of the exhibition, which is not circumscribed by the limits of the medical art of Hippocrates, but aims to cover all aspects of the art of healing among the Byzantines. The objective is to illustrate the links between the methods and practices that were available to the Byzantines, and the central role of the concern for health, bodily, and spiritually in their daily lives.

The prescriptions of Byzantine physicians ordered a combination of medical recipes, diet, and baths. In the medical writings of famous physicians, such as Alexander of Tralles (c. 525-c. 605 CE), one also finds chapters devoted to natural remedies, including amulets. The old practice of curing by water in natural hot springs has gained renewed universal popularity in recent years. Baths were an essential part of medical therapy in Byzantium. In conjunction with the public baths and those available in mansions and palaces, baths were incorporated into the architectural planning of hospitals, while bathing pools became a required element of Byzantine healing sanctuaries. Hygiene and purification are essential features in the practice of health, and through this central concern, the secular and the religious worlds intersected.

Exorcisms, prayers intended to attract divine blessing, rituals and practices (such as the stamping of drinking vessels, perfume bottles, and bread), protective inscriptions, and devices on jewelry, all assisted the Byzantines in their fight against the evil forces believed to be the origin of all illnesses and, of course, death.

JW: How did Byzantine conceptions of health, ailment, and healing progress over time?

BP: To answer this question, I called upon the expertise of Dr. Petros Bouras-Vallianatos, from King’s College in London, who contributed both to our exhibition catalogue and subsequent symposium.

Following classical Hippocratic theory, Byzantine medical authors believed that the body was made up of four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Every disease was considered to be the result of an excess of a humor or a combination of them (dyskrasia). Therefore, a physician was supposed to be able to counterbalance the humors by prescribing an appropriate diet or to remove the noxious humor(s) through the administration of appropriate purgatives or various techniques of blood-letting, thus restoring the patient to health (eukrasia).

Byzantines utilized herbs and various plants for their medicinal properties. Arbutus andrachne – Strawberry tree. Specimens collected during John Sibthorp’s botanical explorations of the Ottoman Empire (1786-1787 CE and 1794-1795 CE). Sibthorbian Herbarium, accession Sib-0926a. Oxford University. Herbaria. (Courtesy: Pera Museum/Pera Müzesi.)

Byzantine medical authors made significant advances in the field of diagnostics, and, in particular, in uroscopy. Theophilus Protospatharius (c. the ninth century CE) is credited with the association of 20 different urine colors with various ailments. Perhaps the most innovative contribution was made by the late Byzantine medical author John Zacharias Aktouarios (c. 1275-c. 1330 CE), who introduced a special urine vial divided into eleven specific areas. Aktouarios relates the particular places in the vial to the human body, suggesting, for example, that various particles found in the upper part are related to affections of the head and so forth.

In the field of surgery, there are many notable examples throughout the Byzantine era showing an unceasing practice of invasive techniques. For example, during the reign of Constantine VII (r. 913-959 CE), a spectacular operation seems to have taken place in which Siamese twins, connected at the upper abdomen, were separated after one of them had died. Finally, in the field of pharmacology, we notice a persistent experimentation and subsequent introduction of new drugs for a variety of illnesses, such as in the case of Alexander of Tralles’ recommendations for epilepsy. From the late 11th century CE onward, there is an attested gradual enrichment of the Byzantine medical cabinet with pharmacological plants, such as galangal, zedoary, and sandalwood, originating in far off places, like the Himalayas and Java, which suggests that Byzantine medicine had been extremely dynamic and open to outside influences.

JW: Life is Short, Art Long underscores the coexistence between a rational understanding of health and medicine based on the teachings of Hippocrates, and the belief that illnesses were primarily caused by demons or other wicked beings.

Was it a challenge, as a curator, to organize this exhibition, given this dichotomy in the Byzantine approach to healthcare, Dr. Pitarakis?

BP: The strong separation of medicine and science from the categories of religion, superstition, and magic seems to have grown out of the Western Enlightenment of the 18th century CE. In Byzantium, the frontiers between these categories were not clearly delineated, and people in search of healing alternatively went to physicians, hospitals, holy men, healing sanctuaries, and magicians. Faith and superstition were strongly anchored features of Byzantine civilization, and the Byzantines switched from one healing method to another in a very natural and spontaneous way.

Two museum visitors gaze upon one of the many icons exhibited in “Life is Short, Art Long.” (Courtesy: Pera Museum/Pera Müzesi.)

In the exhibition, we focused on the role of water as a linking agent among the different healing methods, but we have also attempted to draw other parallels: for instance, the perfumed oils distributed in healing sanctuaries after coming into contact with sacred relics and the medicinal oils or those that served for purposes of hygiene and adornment; the surgical instruments held by physician saints depicted on painted icons and carvings, and those actually used by practicing physicians; the gathering of crowds of sick people, such as the paralytic, the blind, and the demoniac, around a sacred spring; and the 3D animation of the Unkapanı cistern, next to the Pantokrator Monastery, to evoke a hospital housed within a monastery and its adjacent bath. (A detailed description of the organization of the Pantokrator hospital is available in the foundation chart of the monastery copied in an 18th-century manuscript held by the Library of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. A digital copy of which is available in the exhibition.)

The challenge in the organization of the exhibition was not really a dichotomy in the Byzantine approach to healthcare, but the difficulty in illustrating, in a concrete manner, the rich information collected in written sources that do not find a counterpart in the available material culture of the Byzantine period. In these instances, we resorted to materials from other periods, both earlier and later. The attested vocabulary on the range of surgical instruments used by the Byzantines is very rich, but few Byzantine instruments have come to us. However, as the major types did not change throughout the ages, we selected a complete set from the Roman period, to which we added a few Byzantine examples.

To evoke the Byzantine manuscripts of Dioscorides (c. 40-c. 90 CE), the father of modern pharmacology, we presented a selection of plant specimens that John Sibthorp (1758-1796 CE), the eminent British botanist, had collected in Asia Minor and Greece, and identified with the aid of an engraved, illuminated copy of the sixth-century CE Vienna Dioscorides. To illustrate the practice of symbolically binding demoniacs with chains and collars, we used a silver example from 19th-century Cappadocia, while icons and engravings of the 19th century allowed the evocation of miracles at the Byzantine shrine of the Zoodochos Pege (today Balıklı).

JW: The Byzantines’ central role in the transmission of medicinal knowledge to future generations is also highlighted within the exhibition. Many are aware that Byzantine medical practice was grounded in ancient Greco-Roman medicine and that the 12th century CE ushered in a significant transferal of knowledge between Byzantium and the Islamic world.

To conclude our interview, I wanted to ask if you could share a few thoughts about the Byzantine legacy of medicine. How can we best understand and appreciate the Byzantine imprint on modern medicine?

BP: The vast majority of Byzantine medical texts was translated into Latin in the Renaissance and met a considerable reception attested in several reprints during the following centuries. As Dr. Bouras-Vallianatos tells us, they invariably influenced European physicians, who are credited with the most important medical discoveries of the early modern period, such as the circulation of blood by William Harvey (1578-1657 CE). The aforementioned graduated urine vial by the Byzantine physician Aktouarios was well received not only by educated physicians, but it became familiar enough to show up in 16th-century CE English and French vernacular texts aimed at a fairly broad medical audience. As late as 1844, the English physician Francis Adams published a translation of medical handbook by Paul of Aegina (fl. early seventh century CE).

Nineteenth-century physicians must have been impressed by Paul’s detailed descriptions of operations for varicose veins and various types of hernias. Lastly, the Byzantine tradition remained alive in the numerous iatrosophia — medical notebooks and therapeutic compendia written in Greek — reproducing recipes of Byzantine physicians across various Greek-speaking places in the Balkans until the early 20th century. This is the case of the recently edited early 20th-century recipe book owned by the Cretan traditional healer Nikolaos-Konstantinos Theodorakis (1891–1979) that shows how Byzantine medical lore survived unchanged until this day.

JW: Dr. Pitarakis, I thank you so much for sharing your expertise and time with us. We are looking forward to covering another exhibition at the Pera Museum in the near future!

BP: Thank you very much for inviting me to this interview, James! It was a thought-provoking experience, and I hope that it will not only create broader interest in the exhibition and its catalogue, but also the history of Byzantine civilization.

Life is Short, Art Long: The Art of Healing in Byzantium will be on show at the Pera Museum, in Istanbul, Turkey, until April 26, 2015. The show is accompanied by a handsome exhibition catalogue.

Dr. Brigitte Pitarakis is a researcher at the CNRS (Centre national de la recherche scientifique) in Paris, France. Specializing in the history of Byzantine art, Pitarakis’ fields of interest include reliquaries and other religious objects–from Late Antiquity and Byzantium–as well daily life in the Byzantine Empire, Byzantine material culture, and Byzantine social history. Pitarakis is the author of many articles and several books in French on these subjects.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Pera Museum have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Ms. Fatma Çolakoğlu, Head of Film, Video and Communication Programming at the Pera Museum and İstanbul Research Institute, for helping facilitate this interview. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.