In this special guest post, Ms. Susan Abernethy of The Freelance History Writer introduces Ancient History et cetera readers to the compelling life and achievements of St. Hilda of Whitby. Renown for her piety and learning, Hilda is one of the most appealing and yet elusive figures from the Early Middle Ages (or Late Antiquity). Thanks to her vigorous activities, Hilda’s religious and political influence ensured that northern England remained Christian, while many, including The Venerable Bede, attested to her reputation for intellectual brilliance. In 2014, we celebrate the 1400th anniversary of her birth.

In this special guest post, Ms. Susan Abernethy of The Freelance History Writer introduces Ancient History et cetera readers to the compelling life and achievements of St. Hilda of Whitby. Renown for her piety and learning, Hilda is one of the most appealing and yet elusive figures from the Early Middle Ages (or Late Antiquity). Thanks to her vigorous activities, Hilda’s religious and political influence ensured that northern England remained Christian, while many, including The Venerable Bede, attested to her reputation for intellectual brilliance. In 2014, we celebrate the 1400th anniversary of her birth.

Whenever I hear the term the “Dark Ages” I cringe a little bit. This term has fallen out of use, but you still hear it occasionally. The more I’ve studied medieval history, the more I see this era of history wasn’t “dark” at all. There are some “rays of light” that appear to us, even with the non-existent to scant documentation we have. One of them is St. Hilda of Whitby (c. 614-680 CE).

The history of England going back to the Roman conquest and withdrawal is shrouded in mystery and legend. We know the Romans left Britain in the mid-fifth century CE, but the reasons for their sudden departure are still debated by historians. In the vacuum that was left, the Anglo-Saxons moved in. Did they come as invaders or immigrants? Or were they mercenaries under the Romans and just stayed? Why did they come to power after the Romans abandoned their distant island conquest? These questions are still difficult to answer. We know the Anglo-Saxons carved out several kingdoms on the island and then began fighting among themselves for supremacy and unification. Hilda’s relatives were among them. Alongside this political discord, the Roman church sent missions to the island to try to convert the people to Christianity. The religious conversion went hand-in-hand with the political infighting of the powerful Anglo-Saxon kings or bretwaldas, as they were called then.

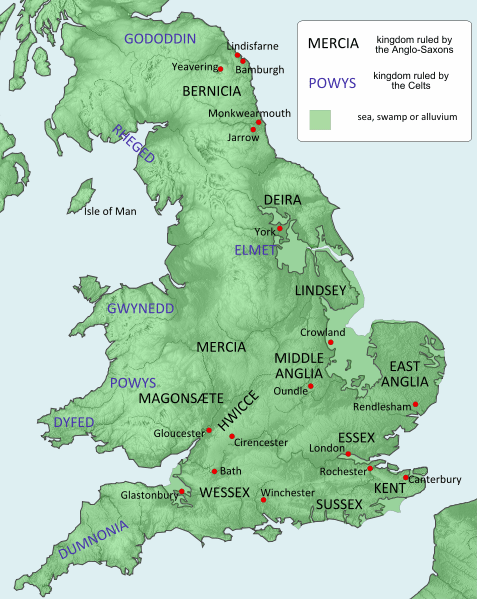

Some of the kingdoms in the east and north of England, which were fighting for supremacy in the seventh century CE, included Northumbria, Lindsey, Elmet, East Anglia, Kent, and Mercia. The bretwaldas would rise and fall from power. Amidst all this strife, the nephew of King Edwin of Northumbria (r. 616-633 CE), a man named Hereric, married a woman named Breguswith. Breguswith gave birth to a daughter named Hereswith and then a daughter who was named Hilda. Hilda was born around 614 CE, most likely at Bamburgh in Northumbria. When Hilda was still an infant, her father was murdered by poison while he and his family were in exile at the court of the king of Elmet in what is now West Yorkshire. Hilda’s uncle, Edwin, took revenge for his nephew’s death by killing the Elmet king and annexing his territory. Hilda and her sister were brought up at the court of King Edwin. Most of what we know of Hilda’s life comes from the Venerable Bede (672-735 CE) in his celebrated Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

On Easter, April 12, 627 CE, King Edwin and his entire court, including young Hilda, were baptized in a small wooden church, which had been erected for the occasion near the current site of today’s York Minster. This was the culmination of a mission by Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590-604 CE). In 597 CE, Gregory the Great had sent Saint Augustine of Canterbury (d. c. 604 CE) to England on a mission to spread Christianity. Augustine had various degrees of success, but one of the monks who traveled with Augustine was Paulinus (d. 644 CE), who eventually became Bishop of York and would have great influence on Hilda’s life and vocation. One of the most important Christian converts during this time was Aethelburh, daughter of King Aethelberht of Kent (560-616 CE). She went to Northumbria to marry King Edwin, and Paulinus accompanied her. Aethelburh practiced her religion, influencing her husband and his court, leading to the mass baptism on that Easter Sunday.

Until the year 647 CE, we know little about Hilda. Because she was a princess, it’s possible she married, maybe even more than once. And maybe she was widowed due to illness or war. Hereswith, Hilda’s sister, became a nun in one of the convents located in the Seine basin (in what was then Merovingian France), when Hilda was about 33. We know that Hilda made her way to East Anglia, perhaps with the intention of joining her sister overseas. But by the end of the year, she was recalled to Northumbria by St. Aidan (c. 590-651 CE), the renowned Irish missionary and Bishop of Lindisfarne.

Until the year 647 CE, we know little about Hilda. Because she was a princess, it’s possible she married, maybe even more than once. And maybe she was widowed due to illness or war. Hereswith, Hilda’s sister, became a nun in one of the convents located in the Seine basin (in what was then Merovingian France), when Hilda was about 33. We know that Hilda made her way to East Anglia, perhaps with the intention of joining her sister overseas. But by the end of the year, she was recalled to Northumbria by St. Aidan (c. 590-651 CE), the renowned Irish missionary and Bishop of Lindisfarne.

Hilda’s Mission

Aidan asked Hilda to establish a small band of women under monastic rule on the north bank of the Wear River. While she lived and ruled in this place, Hilda and her companions learned the traditions of Celtic monasticism as taught by Aidan, much in the same way as it was practiced in the monastic community of Iona (located in the the Inner Hebrides of present-day Scotland). In 649 CE, Aidan asked Hilda to succeed St. Heiu (fl. 620s CE), abbess of the religious community at Hartlepool. Bede tells us Hilda ruled her community according the maxims of monastic discipline, which she learned from wise men. These included purity, justice, devotion, peace and love. Aidan and other holy men would visit and advise her on a regular basis. After a decisive victory by Hilda’s relative, King Oswy of Northumbria (642-670 CE) over King Penda of Mercia (c. 626-655 CE), Oswy dedicated his daughter, St. Aelflaed (654-714 CE), to Hilda to be brought up as a nun, which was a common practice at the time. No trace of the abbey at Hartlepool exists, but remains of its cemetery have been found close to the present St. Hilda’s Church.

About two years later, Hilda came into possession of an estate of about ten hides at the headland of Streanaeshalch, which was later renamed “Whitby” by the invading Danes. Hilda founded and governed a Christian community and monastery, which contained both sexes. Bede tells us the community practiced all virtues, especially love, charity, and peace. Everyone studied the Scriptures and was required to do good works. No one was rich and no one was poor, but all shared in the property communally. What archaeological evidence we have today indicates the monastery was in the Celtic style. The members lived in small houses, usually with two to three to a house. Men and women lived separately but worshiped together.

Hilda was energetic and a master administrator and teacher. Bede tells us that due to her outstanding devotion and grace, everyone called her “mother.” She was considered so wise that kings and princes sought her out for advice. But she was also very concerned with ordinary people. One of her best-known protégées is one of the sheepherders from the monastery named Caedmon. He was inspired by a dream to write and sing verses in praise of God. Hilda recognized his God-given gift and encouraged him. Five men from the community of Whitby would later become bishops, and two of these men would also become saints: John of Beverly (d. 721 CE), Bishop of Hexham, and Wilfrid, Bishop of York (c. 633-c. 709 CE). They would be instrumental in the struggle against paganism along with Hilda.

The Synod of Whitby

The height of Hilda’s influence was demonstrated in the autumn of 663 or the spring of 664 CE when she hosted the Synod of Whitby. In Northumbria, along with the politics of the time, there were two strains of Catholic Christianity, and they could not be reconciled: Celtic and Roman. Celtic Christianity, which emanated from Ireland, was less structured than the Roman variety. The Celts were independent, wandering from place to place all over Europe, where they would establish centers of learning and teach. Celtic Christianity relied on monasteries and abbeys where the abbot was supreme rather than the cathedral and bishop system the Romans followed. The Romans viewed the Celtic brand of Christianity as “rural.”

There were also minor variations of liturgical practices and clerical haircuts but for the most part these could be dealt with. The main difference was the practice of calculating the date of Easter. It was generally agreed Easter should be celebrated on the Sunday of the third week of the month in which the full moon fell on or after the vernal equinox. The Celts adopted the 25th as the date of the equinox, and the rest of Christendom adopted the 21st. The discrepancy sometimes resulted in two Easters, one month apart.

King Oswy’s Kentish born queen, Eanflaed (626-685 CE), followed the Roman dates much to the annoyance of her husband. There were also political considerations for Oswy; in his pursuit of power and consolidation, he needed the Roman Christian area’s support without losing the backing of the Celtic Christian parts of England and his kingdom. In a demonstration of Oswy’s confidence and respect, he asked Hilda to host a critically influential conference at her community of Whitby to debate the issue of Easter and come up with a conclusive answer of which strain of Christianity to maintain. This meeting wasn’t really a synod in the religious sense as much as it was a Witan (or Witenagemot): A political council convened by a king, attended by nobles and advisers, where the king would come to a decision and pass judgement.

The debate was long and acrimonious. Hilda argued for the side of the Celts, most likely due to her friendship with Aidan. In the end, Oswy declared he must choose between the “Roman” St. Peter the Apostle (d. 64 CE) and the teachings of the “Celtic” St. Columba (521-597 CE). He decided to obey St. Peter to whom were given the keys to heaven by Christ. This decision by the most powerful monarch in the kingdom carried great weight and gave the Roman party the upper hand. Thus, the Easter controversy in Western Europe was ended. The Bishop of Lindisfarne, St. Colmán (c. 605-675 CE), withdrew first to Iona and finally to Ireland. Northumbria was without a bishop, and the vacancy was filled by one of Hilda’s protégées, Wilfrid, who had argued forcefully for the Roman faction at the conference. Wilfrid eventually established a See at York. Hilda gracefully accepted and adopted at Whitby the changes made at the synod.

Hilda’s Death & Legacy

Beginning in 674 CE, Hilda began to suffer from a succession of feverish attacks. While ill, she still managed to govern her communities, but she eventually died in 680 CE in her 66th year. Bede tells us there were wonders and visions seen at her death by the nuns at Whitby and at the independent community at Hackness, which she had started in the last year of her life. Oswy’s daughter, Aelflaed, had been groomed by Hilda to succeed her, and she took over as abbess. Tragically, the religious community at Whitby was so completely destroyed by the Danes that nothing remains of either its records or its foundations.

Due to the attack, the community was dispersed, and the Abbott Titus fled to Glastonbury, taking Hilda’s relics with him. There was no attempt to replace the monastery until after the Norman Conquest, when William de Percy (d. 1096 CE), a Norman knight, re-founded Whitby. De Percy’s buildings were mostly pulled down, and the monastery was rebuilt on a much larger scale in the 13th and 14th centuries CE. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries by King Henry VIII (r. 1509-1547 CE), the roofs were removed. Most of the walls remained standing until 1763 CE, when the entire western side of the monastery was blown down. Because of the exposed position of the ruins, the destruction and decay was rapid. Other parts — such as the central tower and choir walls — collapsed in the 19th century, and only a small part of the church is left standing on a cliff about 200 feet above the North Sea.

Although nothing much of her monastery remains, Hilda’s greatness as a scholar and a mentor has lived on in her protégées, and in Bede’s enduring admiration. Her exemplary life shines through as a beacon of light from the “Dark Ages.”

Further reading:

- “The Formation of England 550-1042” by HPR Finberg.

- “Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England” by Henry Mayr-Harting.

- The Catholic Encyclopedia 1913.

- “Dictionary of National Biography 1885-1900, Volume 26” entry on Hilda by Edmund Venables.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry on Hilda of Whitby by Alan Thacker.

- “The Ecclesiastical History of the English People” by Bede in the Oxford World’s Classics edition.

- “The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England” edited by Michael Lapidge, John Blair, Simon Keynes and Donald Scragg.

- “Hilda of Whitby” by Ray Simpson.

Image Credits:

- St Aidan visits St Hilda. Stained glass window in Gloucester Cathedral, England, created by Christopher Whitworth Whall (1849–1924). Image taken by Weglinde (2012). (This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.)

- A political map of Anglo-Saxon and Celtic Britain in c. 650 CE. (The names of former kingdoms are rendered into modern English.) Image created by Hel-hama (2012). (This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.)

- Ruins of Whitby Abbey in England. Image taken by Hugh Chappell (1998). (This image was taken from the Geograph project collection. The copyright on this file is owned by Hugh Chappell and is licensed for reuse under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.)

Ms. Susan Abernethy has always loved history. At the age of fourteen, she saw “The Six Wives of Henry VIII” on TV and was enthralled. Truth seemed much more strange than fiction. She started reading about Henry VIII  and then branched out into many types of history. She pursued her passion for history in college, and has remained a lifelong student of European history. Susan’s blog, The Freelance History Writer, is now a contributor to the following websites: Medievalists.net, Historical Honey, Early Modern England, and Mittelalter Hypotheses — A German blog on the Middle Ages.

and then branched out into many types of history. She pursued her passion for history in college, and has remained a lifelong student of European history. Susan’s blog, The Freelance History Writer, is now a contributor to the following websites: Medievalists.net, Historical Honey, Early Modern England, and Mittelalter Hypotheses — A German blog on the Middle Ages.

All images featured in this post have been properly attributed to their respective owners. Unauthorized reproduction of text and images is prohibited. Mr. James Blake Wiener and Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt were responsible for the editorial process. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia. All rights reserved. © AHE 2013. Please contact us for rights to republication.