When you enter the main hall of the Sulaymaniyah Museum of Iraqi Kurdistan, you will encounter two large replicas of the rock-reliefs from the Mountains Merquli and Rabana. I was interested to know how to reach the originals and asked one of the Museum’s employees about it. He said they lie on two mountains outside the city of Sulaymaniyah and that you need someone to take you there because there are no clues on their precise location.

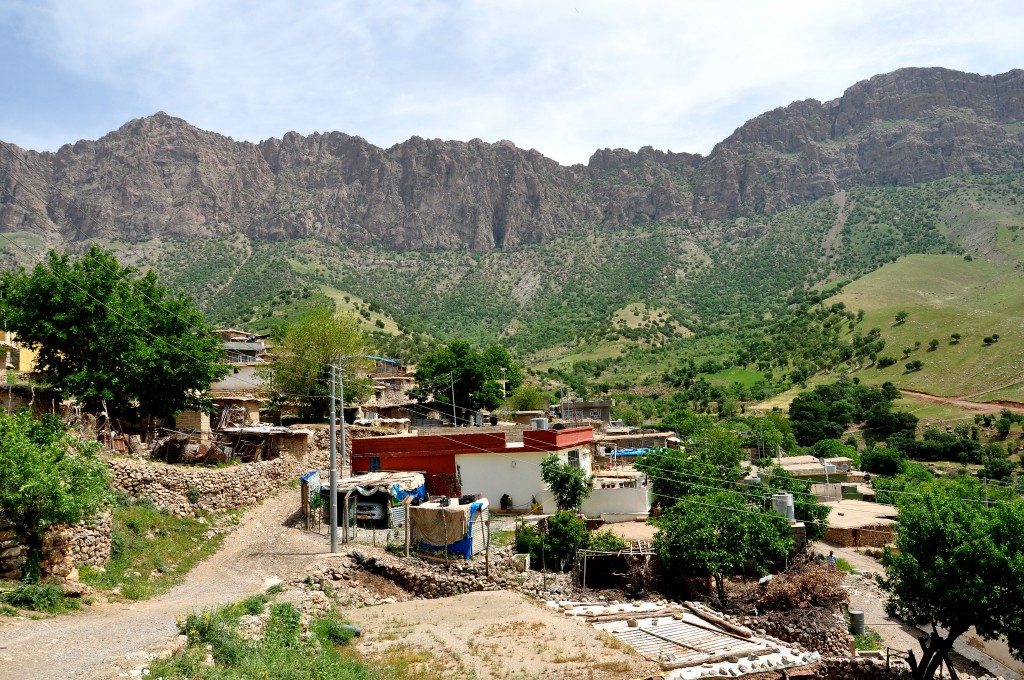

The Mountain Peramagroon (Arabic: جبل بيره مكرون; Kurdish: شاخي پبره مه گروون ) (approximately 9,000 feet / cca. 2,750 m above sea level) lies north and northwest of the City of Sulaymaniyah. It is one of the largest and highest summits in the Governorate of Sulaymaniyah, Iraqi Kurdistan. According to a 2003 article by Professor Andrew R. George, the Mountain has also been associated with the great flood mentioned in of the Epic of Gilgamesh. The mountains (or the sites of) Merquli and Rabana are part of this mountain range and are approximately 40 km north-west of the City of Sulaymaniyah.

I asked one of my patients’ relatives who live in Zewe (a village near mountain Merquli) if he knew how to find the reliefs I was interested in. He said, “I know where Merquli’s relief is, I worked with an archaeological team in 2009 while they were studying the area.”

Rock-relief of Merquli, Friday, May 13, 2013:

(also written Mirqoli and Merculi; Arabic: منحوتة ميرقولي; Kurdish: نه خشي مير قولي)

I met him at Zewe village and left my car there. We started to ascend the mountain at 10 AM. The journey was very exhaustive! I was carrying two backpacks with my Nikon D90 camera, several lenses, water bottles, food, and drinks. After approximately 3 hours, we finally arrived.

The site of Merquli lies about 1,618 m above sea level within the Mountain of Piramagroon (35°45’5.22″N; 45°14’11.61″E). On the summit of the location, there are ruins of what appears to be large stone foundations of a citadel. Approximately 20 m below and 200 m southwest of the citadel, a rock relief was carved on the mountain’s cliff. The rock relief looks over a pass on the summit which leads to the citadel and then to a narrow valley within the mountain.

After the Iraqi Kurdistan region got its semi-independence from Saddam’s Regime in 1991, the General Directorate of Antiquities and Sulaymaniyah Museum tried to do some excavation work in the area. Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, the director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum, said, “Local villagers narrated a legendary story about a man’s relief which lies high up in the mountain and that below/beneath this man, there is a treasure. After we discovered the Rabana’s relief in 1993, we offered local villagers a prize for anyone who discovered this relief. We also did many trips and hikes to the entire area, but we failed to find it.”

The relief itself was found accidentally in February 1999, by a local villager (of Zewe). His name was Choman Ismael Murad. He stated that he ascended to the mountainous top in order get some tree logs. The area of the relief was surrounded by many trees and he sat to get some rest beneath one of the trees. He suddenly saw something on the mountainous cliff which, he said, was a picture of a man, covered by many tree branches (my opinion: although many villagers visited the area every now and then, and that the village and this mountain were part of many battles during the Iraq-Iran war, 1980-1988, the presence of many such trees around and in front of the relief, was the reason behind its lack of discovery). Mr. Choman informed the General Directorate of Antiquities about this discovery.

The relief

The relief is rectangular (210 cm in length; 90 cm in width; and 15 cm in depth). It depicts a standing/striding man; the man occupies 203 cm of the length of the rectangle. The man looks to his left side, towards the entrance into the pass to the citadel. He has a beard and wears a cylinder-shaped head cap (27 cm in length) with a upward-convex-in upper margin. The lower end of the head cap is wrapped with a long piece of cloth which has a knot at the back; the two ends of the cloth hang downward to the lower shoulder level for about 45-47 cm (the overall depiction is very similar to the headdress and its lapets of the Neo-Assyrian kings).

The man’s face is a profile, looking to the left side. His beard is relatively long and pointed while his long mustache ends curved up. He wears a long rope which seems to be fixed on a body dress by a pin (at the upper chest) and at the waist by a ribbon. The knot of the ribbon is located at the upper abdomen/lower chest and its ends were sharp, pointed and hang down for about 46-47 cm to the lower thighs. The rope and body dress (115 cm in length) end just below the knees.

He wears what appears to be a shoe (not a sandal) of 33 cm. His feet are striding. The right arm is raised to chest level, in a greeting, or he may be pointing towards the nearby citadel.

The relief contains no inscriptions or signs. Therefore, it is difficult to estimate which period this relief belongs to. The overall depiction of the man and his clothes may refer to a local Parthian ruler or a nobleman. However, during the 2009 excavations, only a few items had been found, such as glazed ceramics, which date back to the Sassanian period. Saber and colleagues concluded that “the site consists of large stone foundations, where there are possibly several structures that are interrelated, and a likely wall surrounding the settlement or fortification. A number of the stones associated with these features are visible on the surface. While there is some evidence of fire, the site was likely abandoned, as no extensive burning was found. In fact, relatively few artifacts are found on the site, with contents from the site having likely been removed in antiquity or even eroded” (Report on the Excavations at Merquly: The 2009 Season). I took several pics of the location, relief, citadel’s remnants, and nearby structures, and afterwards we descended to the village. I was invited by my companion’s uncle to enjoy a meal with them (he was my patient) and ate shish kabab! I returned home at night thinking their hospitality was unlimited.

The next week I was supposed to visit the nearby Rabana’s rock-relief, but I failed to find someone who could take me there. After few weeks, I found some people but, each time, we postponed the trip to the next week. At last in late March 2015, Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, the director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum took me there while I was making an investigation on Iddi-Sin’s stela.

The rock-relief of Rabana, April 3, 2015

The rock relief of Rabana is located 4 km north to the rock-relief of Merquli. It lies about 2 km to the east of Qarachatan village. It was carved 5 m above the ground surface on the right side of an entrance into a valley within Mountain Rabana.

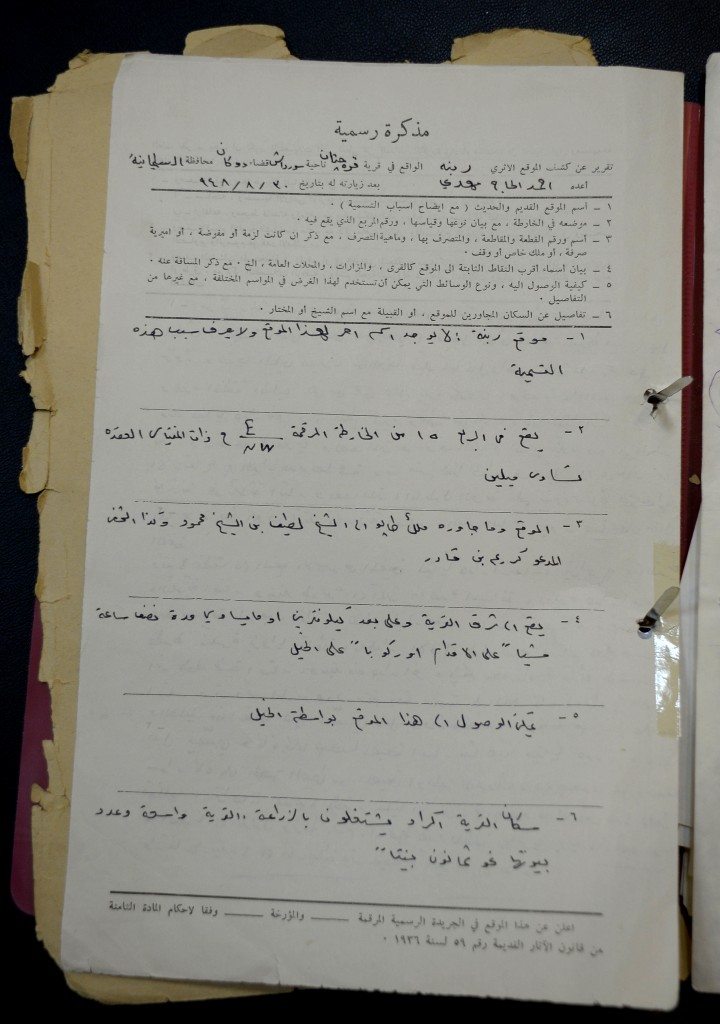

In July 1949, Mr. Ahamed Al-Haj Mahdi, who worked for the General Directorate of Antiquities at Baghdad, made a visit to survey and register the archaeological sites in Sulaymaniyah. While he was visiting Surdash village (about 10 km north to Qarachatan village), local villagers told him that they had heard that there is a relief of a young “woman” on a cliff in addition to many remains of ancient stone walls. He headed to the mountain but he could not continue to ascend because of the difficult nature of the area; he returned back without seeing the relief. However, he published what he had heard in an article in Sumer Journal in the year 1950, volume 6, page 270.

During the late 1980s, Martyr Ghareeb Haladini discovered the relief but Mr. Abdulrahman Jalal Saleh was the one who informed the General Directorate of Antiquities in Sulaymaniyah in March 1993. During the Iraq-Iran war, according to his written statement, Mr. Haladini was hiding from a troop of soldiers as he was out of ammo. He climbed a tree and hid within its branches. By chance, he noticed a large relief on the mountainous cliff behind him.

On April 3, 2015, I left my car in Qarachatan village. Mr. Hashim, myself, and few other companions, headed towards Mountain Rabana. The way was not that exhausting like the route to the Merquli’s relief. So this time, I brought my Nikon D610 camera.

The relief

The relief lies within a rectangle of 188 cm in length, 80 cm in width, and 13 cm in depth. The man himself occupies 185 cm of the length of the relief. The surface of the cliff is tilted and steeply; therefore it was difficult to get clear-cut and perfect pictures “en face”.

The overall depiction of this relief is very similar to the rock-relief of Merquli. The man is upright and walking towards to the south. His beard is relatively long and he wears a conical head cap (of 27 cm in length). The cap is also wrapped with a long piece of cloth which is knotted at the back and hangs downwards (for 43-45 cm). There is a necklace around the neck. He wears a long rope on a body dress (of 108 cm); this rope, however, unlike that of Merquli’s man, was fixed on the upper chest by a short ribbon only, not a pin. There is another ribbon knotted at the front surface of the upper abdomen; however, it does not seem to encircle the waist. The rope ends just below the knees. He raises his right hand in a greeting gesture. He looks to his left side, to the south side of Mountain’s valley, where large stone walls are still seen. The man seems if he is pointing towards or greeting a nearby structure (small village, building, temple, etc.). This man also wears a “shoe” (27 cm).

In comparison to the Merguli man, the Rabana man looks younger! Once again, there are no inscriptions or signs on or near the relief. No excavations of any kind were done on the surrounding area.

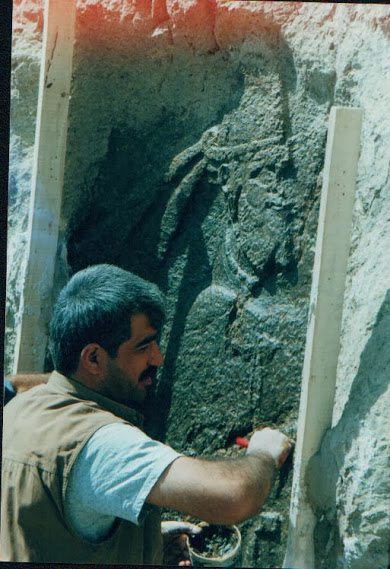

Afterwards, we climbed higher up the mountain and found other large stone walls. An interesting finding was that the ground surface of one of the areas was carved like stairs. These lead to a pit within the mountain’s cliff. Inside the pit, there is a statue of a deity. It should be noted that local villagers know this specific area and that statue is an exposed one. The upper part of the deity was destroyed deliberately in response to one of the Qarachatan’s religious scholar’s advice during the 1940s; this statue represented a fetish according to Islam. It is likely that this place was a temple and it is thought that it dates back to the Neo-Assyrian period, according to Mr. Ahmad Al-Haj Madi’s memorandum.

In comparison:

- The overall depiction of both reliefs is more or less the same. The dimensions of the Rabana relief (and some of its details) are a little bit smaller than those of the Merquli relief.

- It is unknown whether both reliefs were made/carved by the same person and whether they were carved simultaneously or sequentially.

- The Rabana man looks younger than the Merquli man. Therefore, it is unclear whether the depicted man represents one man at two different ages or they were actually two different men.

- There are some differences: the head cap’s shape; the cap’s lapets (they touch the Rabana’s man’s shoulder); the raised arm/hand (the Rabana’s man raises his hand to the upper chest and a little bit beyond it while the Merquli’s man raises it in front of the chest); the upper part of rope; the waist ribbon’s length; and the shoe’s length.

In order to draft my article, I depended on the following:

- Personal interviews with Mr. Kamal Rashid Rahim, Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, and Professor Zuhair Rejeb.

- Saber Ahmed Saber, Zuhair Rejeb and Mark Altaweel (2014). REPORT ON THE EXCAVATIONS AT MERQULY: THE 2009 SEASON. Iraq, 76, pp 231-244. doi:10.1017/irq.2014.9.

-

Mark Altaweel (2012). Some Recent and Current Fieldwork in Iraq. Iraq, 74, pp 167-168 doi:10.1017/S0021088900000346.

-

M. Altaweel, A. Marsh, S. Mühl, O. Nieuwenhuyse, K. Radner, K. Rasheed & S.A. Saber. New Investigations in the Environment, History and Archaeology of the Iraqi Hilly Flanks: Shahrizor Survey Project 2009-2011. Iraq 74: 1-35.

- Kamal Rashid Rahim (2001). The project of Mountain Piramagroon’s relief replicas at Merquli and Rabana. Hazar Merd, 18, pp 153-163.

Who lived near the reliefs? Was it a small village, city, settlement, citadel, or fortress? Is it a co-incidence that the stela of Iddi-Sin, king of Simurrum, was found only a few kilometers from these reliefs? The conglomerate of these Mesopotamian ancient structures within a small area is not an arbitrary one; this is the land of Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization!

I touched the reliefs and other structures while closing my eyes. It was a thrill, a thunderclap amidst a deadly silent mountain, punctuated by the terrifying sound of the wind! I went through a time machine, 2000 years backwards. What a sensation!

Finally, we descended and finished this very fascinating trip! I hope I was successful in delivering useful information about these two rock-reliefs and their surroundings to AHE readership. The net contains very scarce information about them.

I would like to sincerely thank all of those who helped me make this article: Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah (director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum); Mr. Kamal Rasheed Rahim (general director of the General Directorate of Antiquities of Sulaymaniyah); Professor Zuhair Rejeb (one of the key team members of the Merquli’s excavation team); Mr. Hushiyar Yaseen (who took/accompanied me to Merquli’s relief); Mr. Nejem Alddin Ahmad (who accompanied/guided us to Rabana’s relief and invited us at the end of the day to his house with extreme hospitality); Mr. Bahzad Mohammad (who helped me take photos of the stair-like structure and statue of the deity using his iPhone after my camera’s battery died!).

Disclaimer:

Sulaymaniyah (or Slemani) Governorate lies within the northern area of Iraq and is part of Iraqi Kurdistan (or Kurdistan Region or Southern Kurdistan). All of these terms are used to describe the region. Neither the author nor Ancient History Encyclopedia endorses any specific term of the aforementioned ones.