Thanks to our partnership agreement with the EAGLE Portal, Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) will be republishing select EAGLE stories, on a periodic basis, which illuminate special topics pertaining everyday life and culture in ancient Rome. We hope that you enjoy these ancient vignettes, and we also encourage you to explore EAGLE’s massive epigraphic database.

A statue base with two inscriptions carved on opposite sides, one in Greek, one in Latin, stands in the courtyard of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, where it receives very little attention from passing tourists, but sixteen hundred years ago it was at the centre of a row between a high-spirited empress and an equally determined bishop.

The base was excavated in 1847 in the vicinity of Hagia Eirene in Istanbul. This was the centre of ancient Constantinople, an aristocratic residential area called ‘Pittakia’, immediately north of one of the central squares of the eastern capital, the Augusteion.

The Latin inscription, in sober prose states that it (and the monument it accompanied) was dedicated to the empress Eudoxia by the prefect of the city (the highest office holder in the capital), Simplicius. The Greek inscription, an elegant verse in four hexameters, addresses the beholder, praises the imperial city and the noble ancestry of the awarder, and tells us that a porphyry column supporting a silver statue of the empress once stood on top of the base. The city prefect Simplicius is a known figure; he held office in 403, which enables us to date the inscriptions precisely to that year (LSA 27).

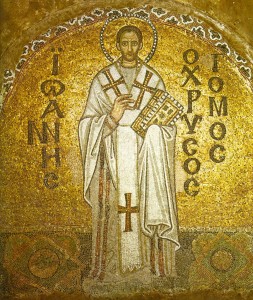

The empress Eudoxia, wife of the emperor Arcadius (383-408) was the most powerful woman of her time, ambitious and famous for her love for luxury. The bishop who became embroiled with her was John, named ‘Chrysostomus‘ – ‘Goldenmouth‘ – by his contemporaries because of his eloquence, and was later proclaimed a Saint and a Father of the Church. Modern historians however dispute his character: should he be celebrated as a saint, an apostle and a martyr, or was he an uncompromising fanatic, aggressive and intolerant in doctrinal matters, a choleric soaked with self-righteousness?

Byzantine Mosaic in Church of Hagia Sofia, (Ayasofia), Istanbul, showing image of St. John Chrysostomos. Inscription reads “IOANNES O CHRYSOSTOMOS”

John was appointed bishop of Constantinople in 398, and he was undoubtedly a highly political bishop. His attempts to establish the primacy of his see caused enmity with other influential bishops. However, John was a popular man within Constantinople itself; that bishops should protect the poor is a thought which imbues all his writings, and the miseries of the poor, which he contrasts with the extravagances of the rich, is a reoccuring topic in his inflammatory sermons. This made enemies in the influential milieu of the capital, and even at court, and it brought him into conflict with the empress herself; she probably rightly interpreted much of the bishop’s invective as aimed against herself.

In 403, the disagreement between empress and bishop reached a peak. Late antique sources tell us that John, preaching in the nearby Hagia Sophia, was disturbed by the noise of celebrations at the dedication of this very statue. Instead of applying to the authorities, as would have been proper, John used his eloquence to ridicule those who had enjoined these celebrations. The empress, as our source Socrates tells us, „once more applied his expressions to herself as indicating marked contempt toward her own person: she therefore endeavored to procure the summoning of another council of bishops against him. When John became aware of this, he delivered in the church that celebrated oration commencing with these words: ‘Again Herodias raves; again she is troubled; she dances again; and again desires to receive John’s head in a charger.’ This, of course, exasperated the empress still more.“ (Socrates, Ecclesiastical History VI, 19).

John was deposed as bishop and forced into exile on the empress’ instigation. Public unrest followed; John’s supporters in Constantinople set fire to the church of Hagia Sophia. An earthquake persuaded the empress that it was God’s will to recall him. Despite this temporary reconciliation, the conflict endured. In 404, John was again banished, and this time his exile lasted until his death in 407. Eudoxia died of a miscarriage shortly after her victory, in 404.

Written by: Ulrich Gehn on Europeana Eagle Portal