When you think of ancient civilizations, what comes to mind? Perhaps you imagine massive pyramids, majestic statues, or vast reliefs carved from stone. This is no coincidence – after all, they are what we see in both museums and ruins today. Stone and other materials such as bone are durable, allowing them to last to the present day and become embedded in the public consciousness at sites such as the Parthenon and the Roman Forum. But what about all of the objects that have been lost to time?

Few wooden artifacts from ancient civilizations survive due to the material’s vulnerability to decay. However, Harvard University’s Giza Project team was able to bring Egyptian wood craftsmanship to life with an ambitious undertaking: reconstructing an elaborate chair that once belonged to Queen Hetepheres.

I recently visited the Harvard Semitic Museum, where the throne is on display in a new exhibition. Queen Hetepheres was mother of the Pharaoh Khufu, who commissioned the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza, and lived over 4,500 years ago.

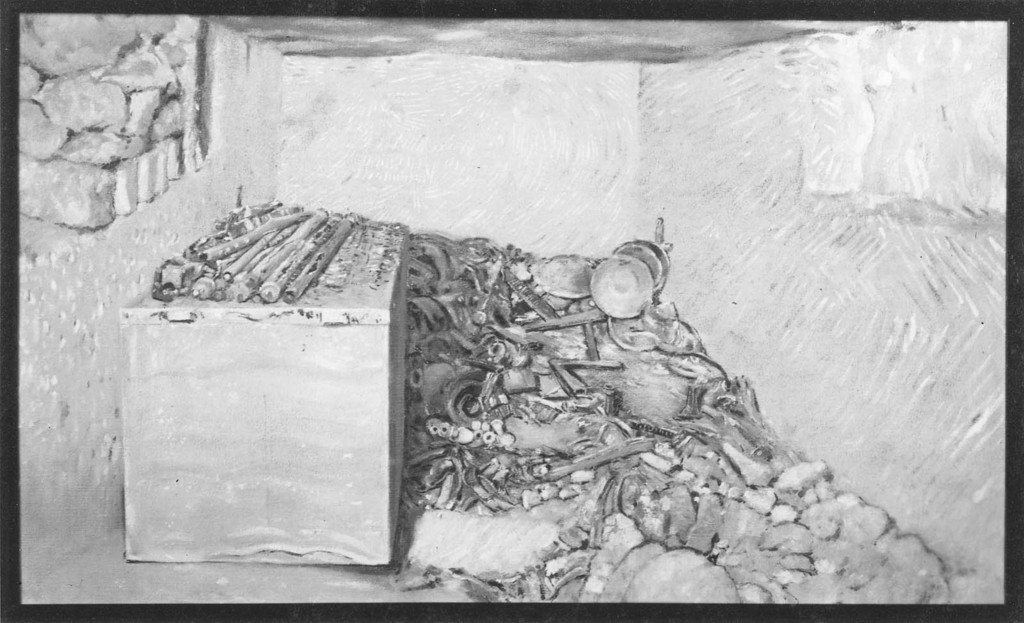

Although the chair on display at the museum is new, its roots lie millennia in the past. A joint Harvard-Museum of Fine Arts expedition to Egypt in 1925 unearthed the deteriorated remnants of the throne in an unfinished burial chamber 100 feet (30 meters) underground at Giza, along with the queen’s sarcophagus and burial equipment. None of the original wood from the chair survived, but thousands of faience, gold, and copper components of the chair were recovered and housed at the Cairo Museum. Modern artists at the Museum of Fine Arts and Cairo Museum reconstructed the other furniture from the chamber, yet never attempted to restore this chair, the most elaborate item in the collection.

The tomb where the remains of the chair were found. Photo © Descendants of Joseph Lindon Smith.

Using modern technology and knowledge of Egyptian craftsmanship, the Harvard Giza Project was able to carefully reconstruct a 3D model of the throne based on the thousands of tiny fragments discovered in the tomb. A computerized milling machine then allowed the team to create an incredibly accurate reconstruction of the throne out of cedar wood. Artists added over 2,600 blue tile inlays made of Egyptian faience, the oldest type of glazed ceramic in history, and painted it with real gold.

Photo © Harvard Semitic Museum.

The throne is on the landing of the second floor of the museum. 4,500 years later, the original artists’ design still communicates the queen’s status and power. It stands alone in a glass case at eye level, commanding attention as visitors walk up the staircase to enter the Egyptian exhibits.

The ornate designs on the sides of the chair caught my attention. Photo © Caroline Cervera.

The exhibit discusses an intriguing mystery as well: typical Old Kingdom burials of Egyptian queens featured small pyramids at the surface, yet Queen Hetepheres’ burial shaft had no such marker and seemed to be hidden behind plaster filling. Her sarcophagus was sealed but empty, prompting debate over whether the chamber was actually a burial or an different type of ceremonial deposit entirely. Millennia after her death, Queen Hetepheres continues to fascinate the ancient history community.

The Giza Project’s latest creation is an incredible example of how recent advances in technology are allowing archaeologists to engineer new ways to experience the past. Creating the throne by hand would have taken years of training and human labor, but using advanced computer modeling, the team was able to reconstruct the chair down to the smallest detail. Its precision makes it an excellent educational tool for students of archaeology and art history. It will be fascinating to see what the Giza Project and the wider archaeological community will do next as even more advanced technology becomes available.

If you ever find yourself in the Boston area, be sure to stop by the Semitic Museum on the Harvard campus. Exclusively devoted to displaying objects from the ancient Near East and Egypt, it is a must for any lover of the ancient world. Admission is free to the public on weekdays from 10-4 and Sundays from 1-4. Visit the museum’s web site here for more information.

Have you visited an exhibition that impressed you recently? If so, why not write about it for AHE?