In 1821 ten paintings were purchased from Mr. Henry Salt (1780-1827) and arrived at the British Museum. The eleventh painting was acquired in 1823. Each painting appeared to have been mounted with a slightly different support material. Finger marks and hand prints on the backs of many of the paintings suggest that the paintings were laid face down onto a surface and that a thickened slurry-mix of plaster was applied to the back of the mud straw. All these paintings have undergone extensive conservation.

In 1835, the paintings were put on display to the public within the “Egyptian Saloon” (now the Egyptian Sculpture Gallery) at the British Museum. They were then given the inventory display numbers (nos. 169-70, 171-81). However, at the beginning of the 20th century they were given their current inventory numbers of EA37976-86. There is little indication that they originally came from the same tomb-chapel.

Wall paintings from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun within their large displaying cases. The paintings are displayed vertically but tilted backward at their upper part. Room 61, upper floor, The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

“We cannot learn from what part of Egypt they came, nor in what kind of place they were found;” this is what one of the earliest guidebooks of the British Museum said. Actually, the paintings’ biographies and sources were very fragmentary and frustratingly vague, as recording of the exact find-spot of objects was not a priority during that period.

Mr. Salt was the British consul-general who took office in Egypt in 1816. He got legal permission from the Ottoman authorities for excavating, removing, and shipping ancient objects to England. He employed many agents, and one of them was a young Greek man whose name was Giovani (known also as ‘Yanni’) d’Athanasi (1798-1854). D’Athanasi excavated an area on the west bank of the River Nile at Thebes (modern-day Luxor). At the same time on the eastern bank, a team of workers belonging to the Italian-born French consul Bernardino Drovetti (1776-1852) were also excavating the land for mummies. However, both teams continually fought about the division of ground and many clashes, often physically violent, occurred. This hostile environment encouraged an atmosphere of secrecy with respect to their daily activities and it unfortunately obscured the exact find-spot of many excavated objects.

So where were these paintings found and when? Though d’Athanasi was very secretive about his work and excavated materials some clues have been found in water-color paintings. During his mission, d’Athanasi resided in a house on the west bank of Thebes, very close to the well-known 18th Dynasty tomb-chapel of Nakht at Gurna village. During his way to explore Upper Nubia Louis Linant de Bellefonds (1799-1883) a French artist and explorer passed through Luxor and met d’Athanasi. Linant visited d’Athanasi’s house and while there drew water-colors of two of the paintings (the Nebamun in the marshes and the musicians playing at the banquet). From these we can recognize the date of July 5, 1821. Therefore, we can conclude the Nebamun in the marshes and the musicians playing at the banquet were recently excavated and within d’Athanasi’s house.

Mr. John Carne (1789-1844) a British author and traveler, wrote to his father that he had spent an enjoyable few weeks with Mr. Salt in the city of Alexandria; the letter was dated August 25, 1821. Carne stated that Salt “had brought with him, from Cairo, some valuable paintings, lately discovered at Thebes.” So far, the paintings had reached Alexandria city and were ready for shipping to the British Museum in London. Mr. Bonham Richard, Salt’s agent and friend, sent a letter to the British Museum saying that a shipload of objects excavated in Egypt by Salt had arrived on the Kate and was currently in quarantine in the Medway estuary; the paintings were among them. The letter was written on the Christmas day of 1821. Mr. Richard included some extracts from Salt’s letters dated back to October 5 and 10, 1821; Salt said that his man (referring to d’Athanasi) discovered ten paintings in the last year (i.e., 1820).

The tomb-chapel’s interior decorated walls were thought to be largely intact when discovered by d’Athanasi. These paintings are probably only a fraction; d’Athanasi’s men perhaps recovered the best-looking or attractive scenes. D’Athanasi’s workmen seemed to remove the smaller scenes at first, but they altered their plan and instead removed larger pieces of the walls. Initially, they probably used saws and knives to cut into the plaster surface of the walls. This had outlined the rectangular pieces chosen for the removal to be pried away later on from their walls with crowbars. Some pieces were removed with their full-thickness intact, while other were very thin and suffered great damage at their edges. D’Athanasi probably deliberately destroyed or at least heavily damaged the tomb-chapel when he had finished his mission. Researchers think that it lies within an area called Dra Abu el-Naga at Luxor.

The hieroglyphic inscriptions on the paintings mention the name of “Nebamun” several times, which means “My Lord is Amun.” However, the name was damaged and the best reserved instance is above a cattle (a caption in the scene of the cattle). Nebamun’s full title was “the Scribe and Grain-accountant in the Granary of Divine [Offerings of Amun].” This title puts him on the lower social range of people with tombs; however, his job and duties connected him to a very powerful institution. Amun was the state-god of the period and was worshipped widely. Nebamun tomb-chapel dates back to the New Kingdom period of the 18th Dynasty, circa 1350 BCE.

The paintings were removed several times, from one safe place to another, during the first and second world wars. They finally returned to their home, the British Museum, on May 7, 1947. During their storage and transportation, some of the paintings suffered some damage. The paintings have been displayed in various halls within the Museum after the years. They underwent extensive and lengthy conservation from 2001 to 2007. Currently, they are on display in Room 61 (the Michel Cohen Gallery, the upper floor). These eleven magnificent pieces of wall paintings from Nebamun’s ancient Egyptian tomb-chapel are among the greatest treasures the British Museum has. They are displayed vertically, but slightly tilted backward at an angle. Each scene is contained within a separate large case and a compact description can be found at the foot and sides of the displaying cases. Smaller fragments can be found in other museums, such as the Egyptian Museum in Berlin (Germany) and Musee Calvet at Avignon (France).

Now, enjoy the paintings:

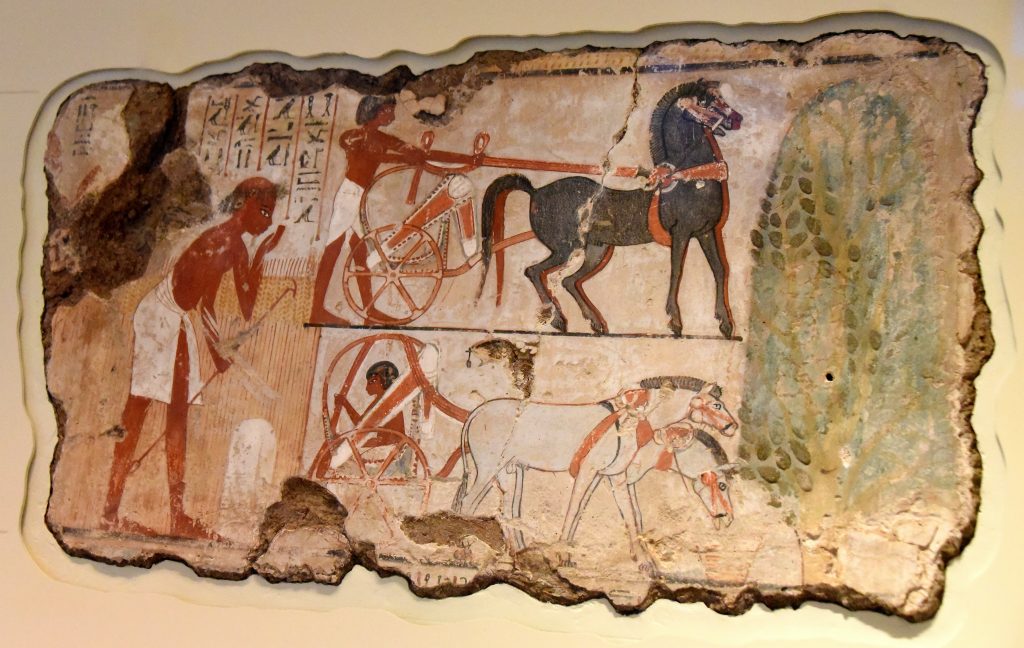

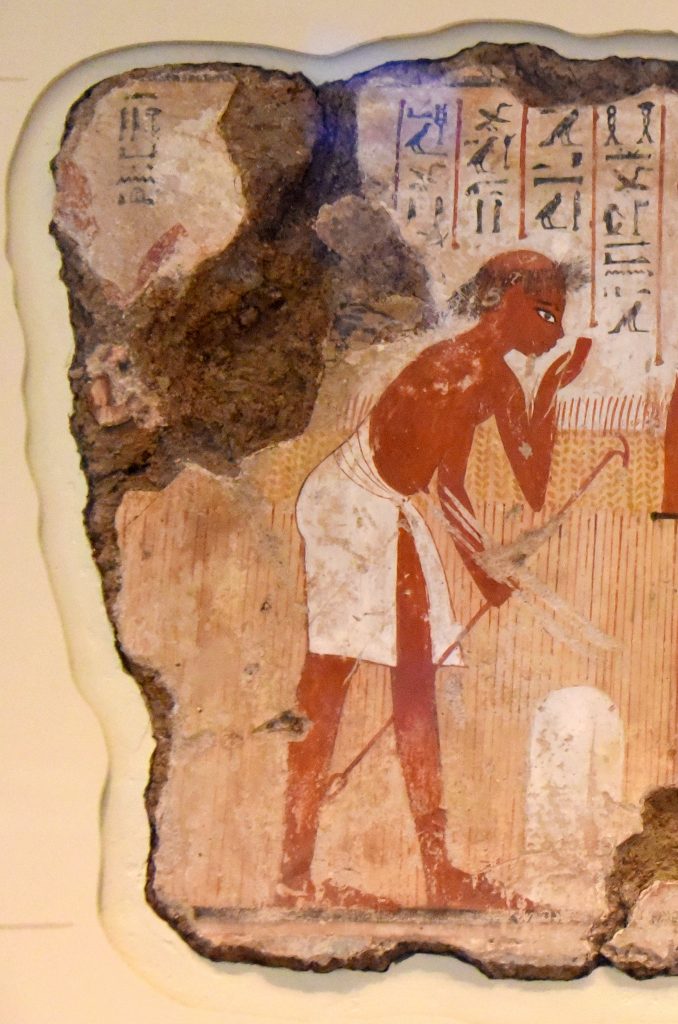

Surveying the field for Nebamun

This scene from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun shows officials inspecting fields. A farmer checks the boundary marker of the field. Nearby, 2 chariots for the party of officials wait under the shade of sycomore-fig tree. Another smaller fragments belonging to this scene/wall, now in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, show the grain being harvested and processed. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The old farmer is shown balding, badly shaven, poorly dressed, and with a protruded naval. He is taking an oath saying “As the Great god who is in the sky endures, the boundary stone is exact!”. “The Chief of the Measurers of the Granary” (mostly lost, the upper left part) holds a rope decorated with the head of Amun’s sacred ram for measuring the God’s fields. After Nebamun died, the head was hacked out, but later, perhaps in Tutankhamun’s reign, someone clumsily restored it with mud-plaster and re-drew it. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

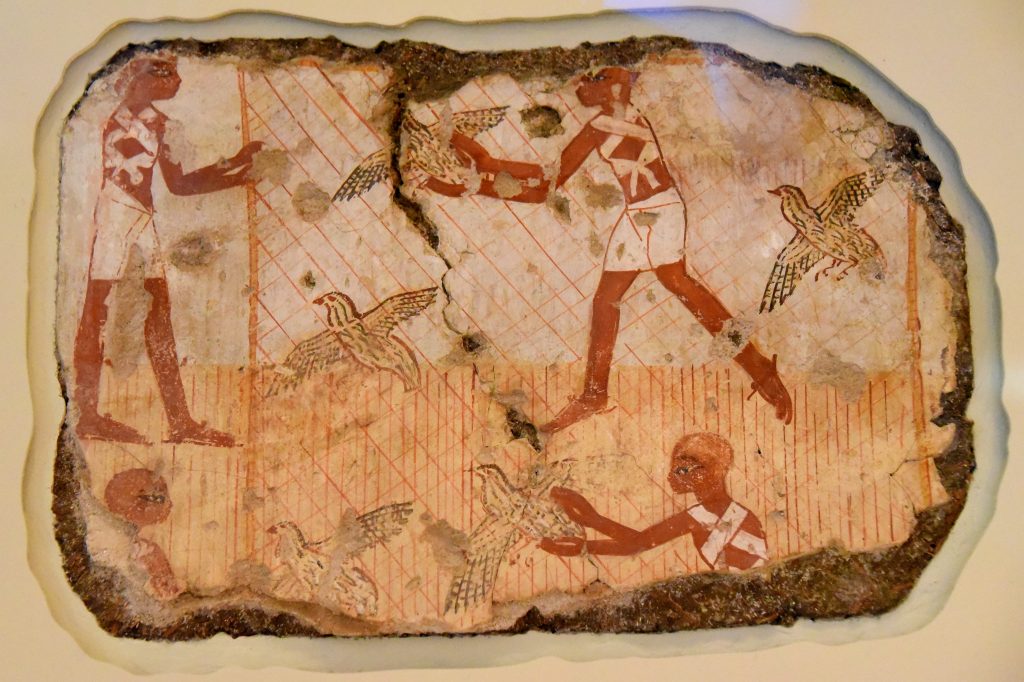

This fragment on loan from Berlin shows men in a filed catching quails in a net. It is thought that Nebamun’s tomb-chapel lies at Dra Abu el-Naga because this fragment was found there in 1890. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

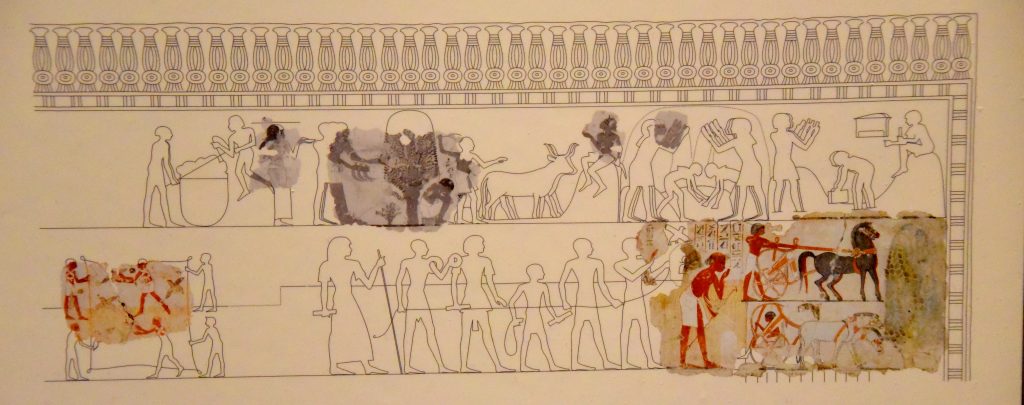

Reconstruction of the whole scene: drawing by C. Thorne and R. B. Parkinson. Photographs of the Berlin Museum fragments by J. Liepe, copyright Agyptisches Museum, Berlin. The British Museum, London. Image © Osama S. M. Amin.

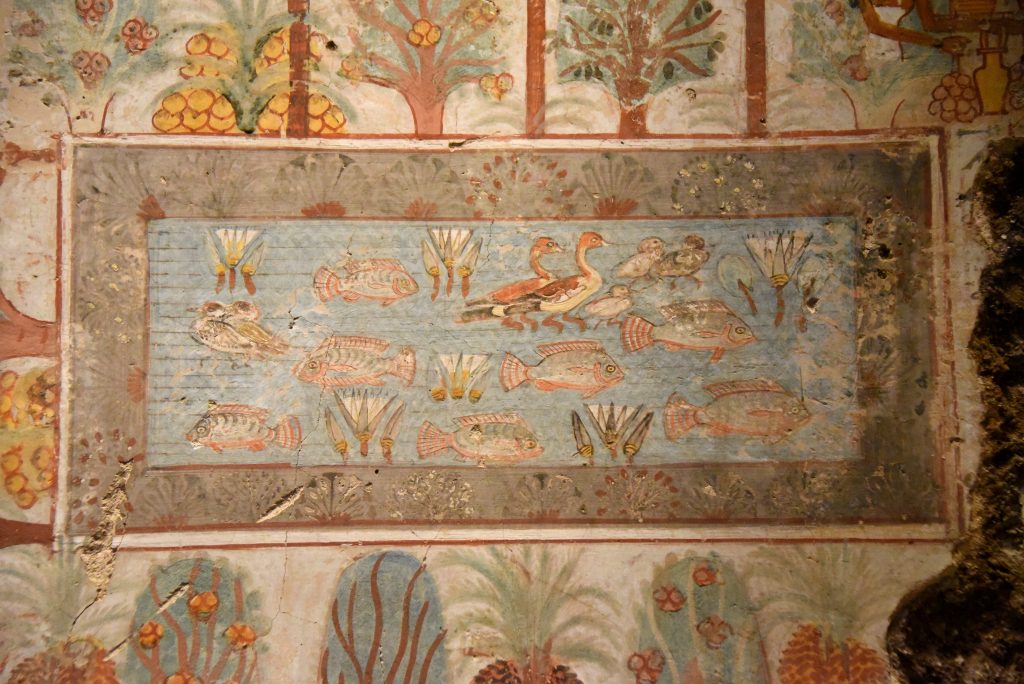

Nebamun’s Garden of the West

Nebamun’s garden in the afterlife is like the earthly gardens of the wealthy in ancient Egypt. The pool is full of birds and fish, surrounded by borders of flowers and rows of trees. The fruit trees include sycomore-figs, date-palms, and dom-palms; the dates are shown in different stages of ripeness. On the right of the painting, the goddess Nut, leans out of a tree, and offers sycomore-figs to Nebamun (now lost). On the left of the pool, a sycomore-fig tree speaks and greets Nebamun as the owner of the garden; her words are recorded in hieroglyphs. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The pool was surrounded with 3 rows of tress, arranged around its edges. The waves of the pool were painted with a darker blue pigment; much of this has been lost, like the green on the tress and bushes. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The goddess Nut in the tree offers sycomore-figs and jars of wine or beer. The artist accidentally painted her skin red at first, but then repainted it yellow, the correct color of a goddess’ skin. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

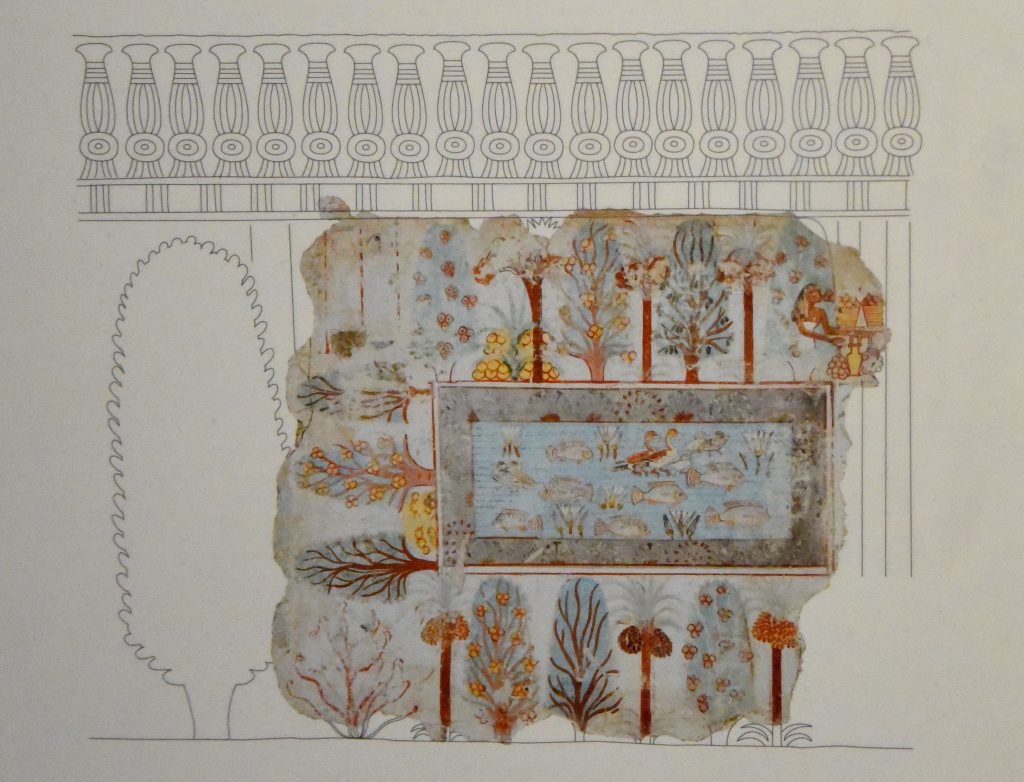

Reconstruction of the scene on the original wall. Drawing by C. Thorne and R. B. Parkinson. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

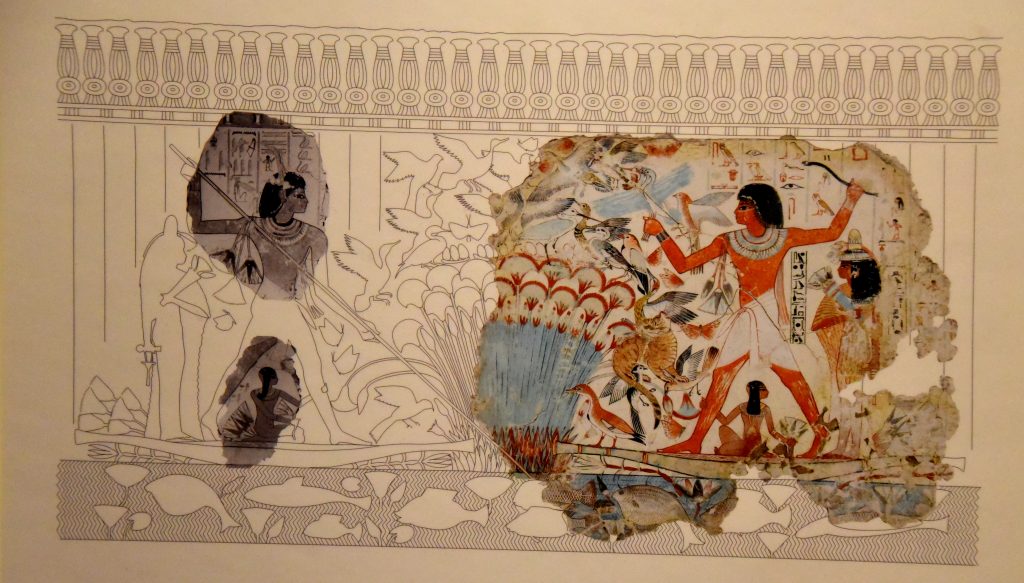

Nebamun hunting in the marshes

Nebamun is in a small boat, hunting birds with his wife, Hatshepsut and their young daughter in the marshes of the Nile. Scenes of leisure had already been a traditional part of tomb-chapel decorations for centuries and they show the tomb’s owner “enjoying himself and seeing beauty” in the afterlife, as the hieroglyphic caption here says. Fertile marshes were the place of rebirth and eroticism, making this more than a simple image of recreation. The huge striding figure of Nebamun dominates, forever happy and forever young, surrounded by the rich and teeming life of the marsh. Hunting not only supplied food, but represented Nebamun’s triumph over the forces of the chaos. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A tawny cat catches birds among the papyrus stems. Cats were family pets, but he is shown here because a cat could also represent the Sun-god hunting the enemies of the light and order. His unusual gilded eye hints at the religious meanings of this scene. The artists have filled every space with lively details. The marsh is full of lotus flowers and Plain Tiger butterflies. They are freely and delicately painted, suggesting the pattern and texture of their wings. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This is Nebamun; his name means “My Lord is Amun”. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

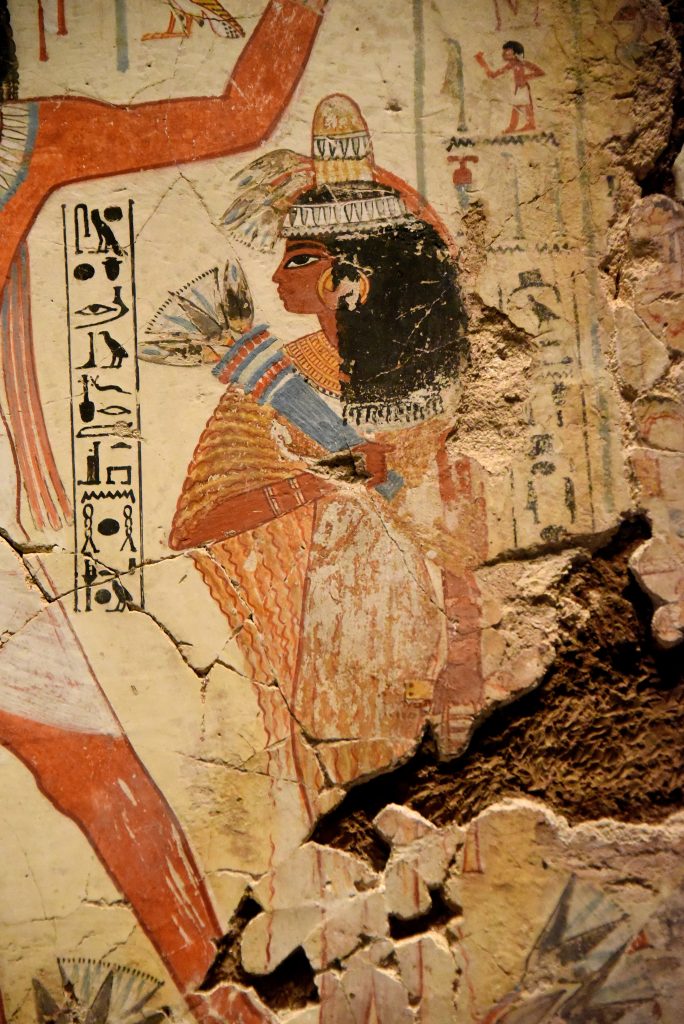

Nebamun’s wife, Hatshepsut, stands behind him. Note her elaborate headdress and dress. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Nebamun’s daughter sits on the boat below the figure of her father. She grips her father’s right leg with her right hand while her left hand holds a lotus flower. She is naked. Note her hair-style! The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Reconstruction of this wall scene. Drawing by C. Thorne and R. B. Parkinson. Photographs of other fragments courtesy of the Association of Egyptologique Reine Elizabeth, Brussels. The British Museum London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

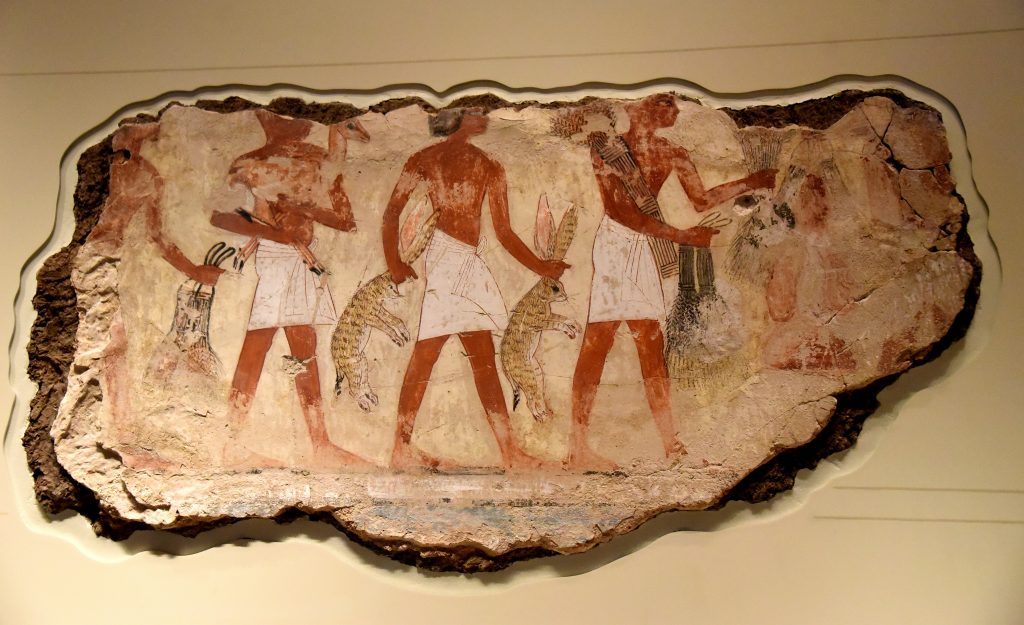

Offering bringers

A procession of simply dressed servants brings offerings: sheaves of grain and desert animals to be food for Nebamun. These include a young gazelle and 2 desert hares. The border at the bottom shows that this was the lowest scene on this wall. The British Museum. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This servant carries a small Dorcas gazelle. It is still alive and he holds it tightly to stop it struggling free. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The servant on the middle holds 2 desert hares. The animals have wonderfully textured fur and long whiskers. The superb draftsmanship and composition make this standard scene very fresh and lively. The artists have even varied the servants’ simple clothes. With one of these kilts, the artist changed his mind and painted a different set of folds over his first version, which is visible through the white paint. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

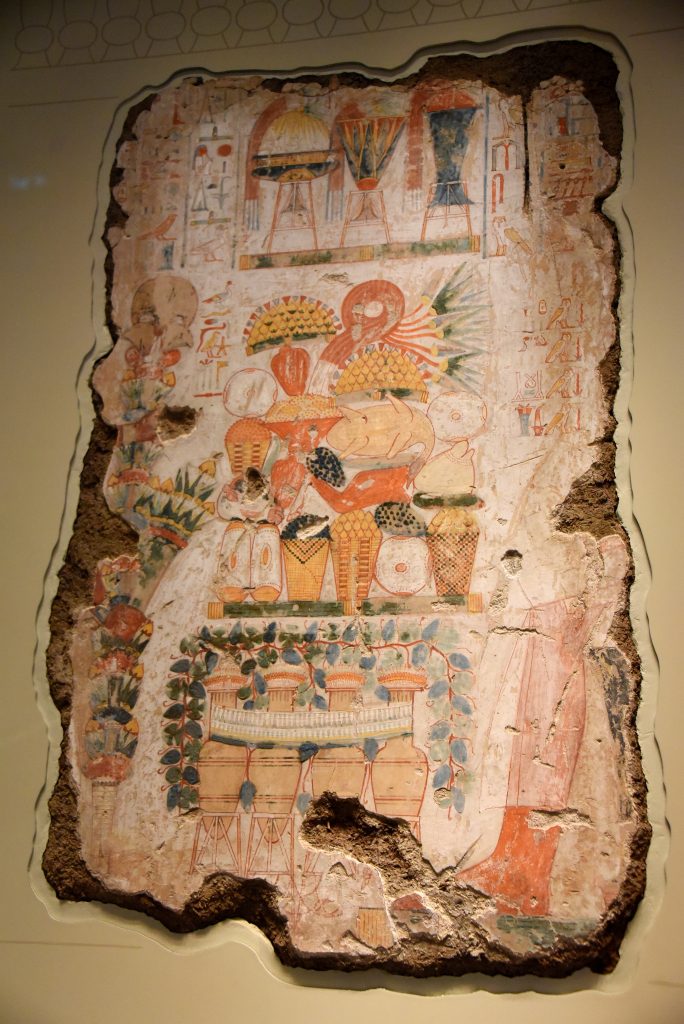

Offerings for Nebamun

This was the most important scene in the tomb-chapel. It is painted in a formal style with white rather than cream background to make it stand out. It shows a huge pile of lavish food before the dead Nebamun and his wife (now lost), with wine and ornate perfume jars. Their son, Netjermes (now lost) offers them a tall banquet of papyrus and flowers, symbolic of the annual festival of the god Amun, when relatives came to visit the dead. The hieroglyphic caption contains funerary prayers and a list of offerings. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The food offerings include sycamore-figs, grapes, differently shaped loaves of bread, and also a roast duck and joints of meat, which only the wealthy could afford. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Large jars of wine are garlanded with grapes and vines. In many places, the green and blue has been lost, since these colors were applied as roughly ground pigments which have fallen away. On the right side, at Nebamun’s leg, traces of red grid-lines are visible in places under the background color. These lines helped the artists to lay out the figures, but they used them only in this scene because it was the largest and most formal in the tomb-chapel. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Nebamun tomb-chapel.

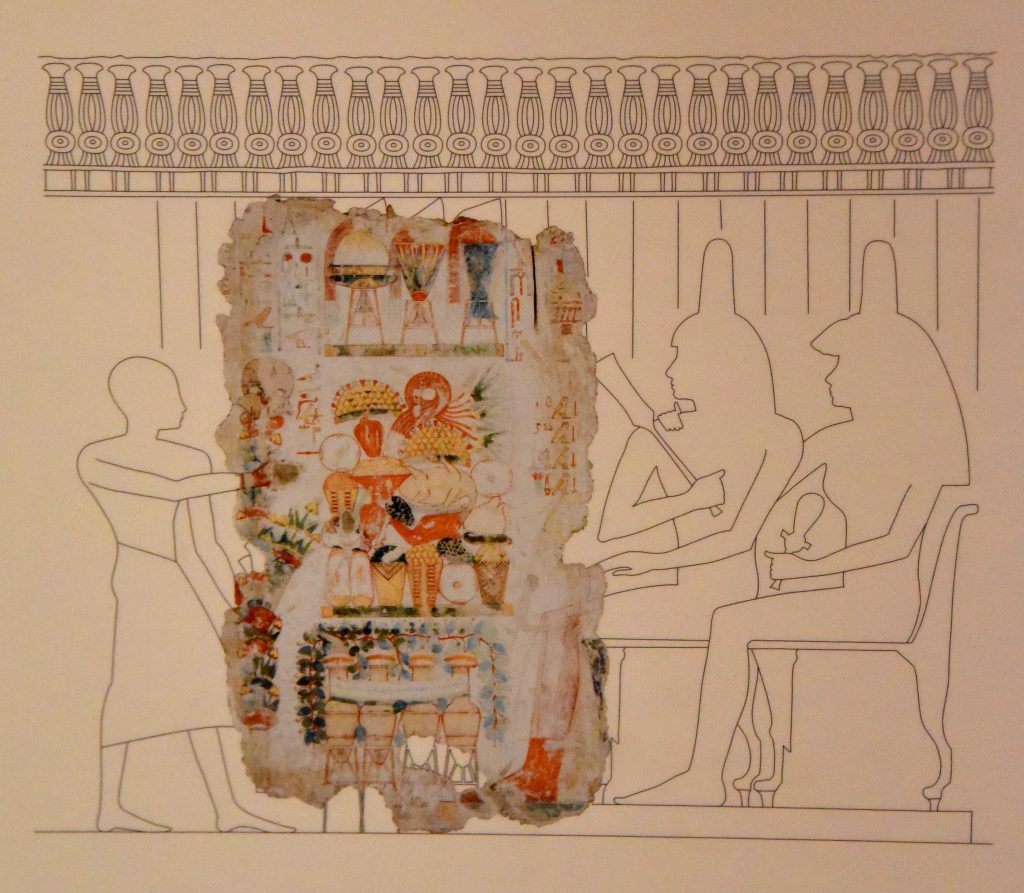

Reconstruction of the wall scene. Drawing by C. Thorne and R. B. Parkinson. The British Museum, London. Photographed and © Osama S. M. Amin. Nebamun tomb-chapel.

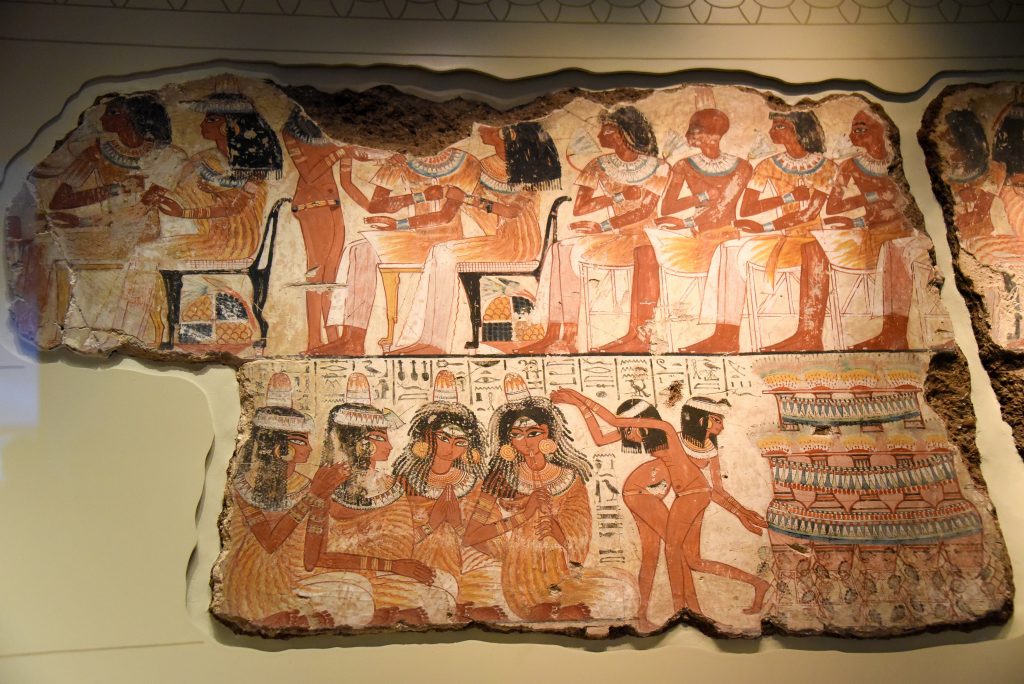

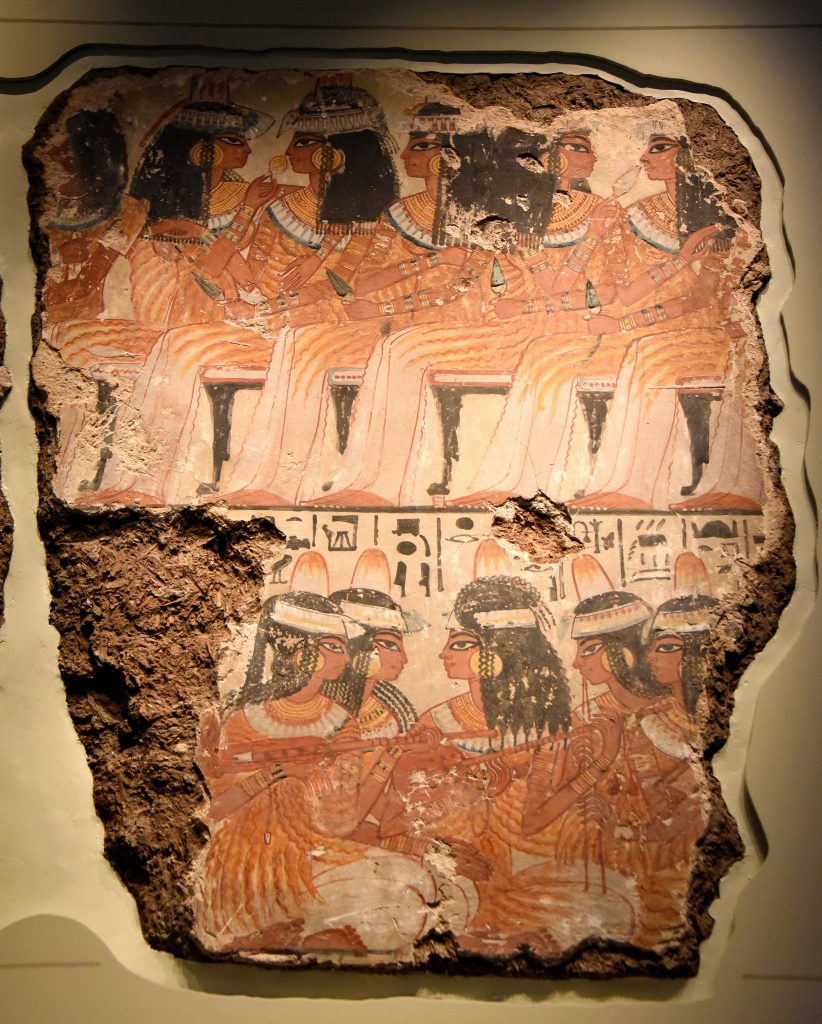

A feast for Nebamun

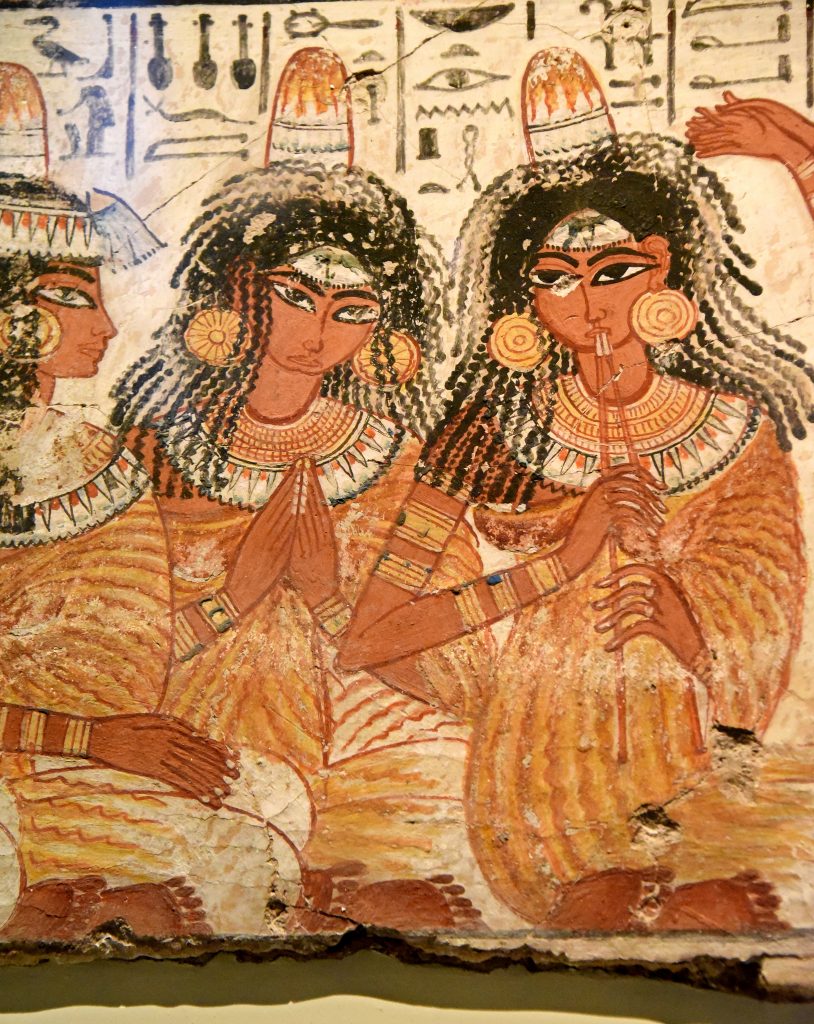

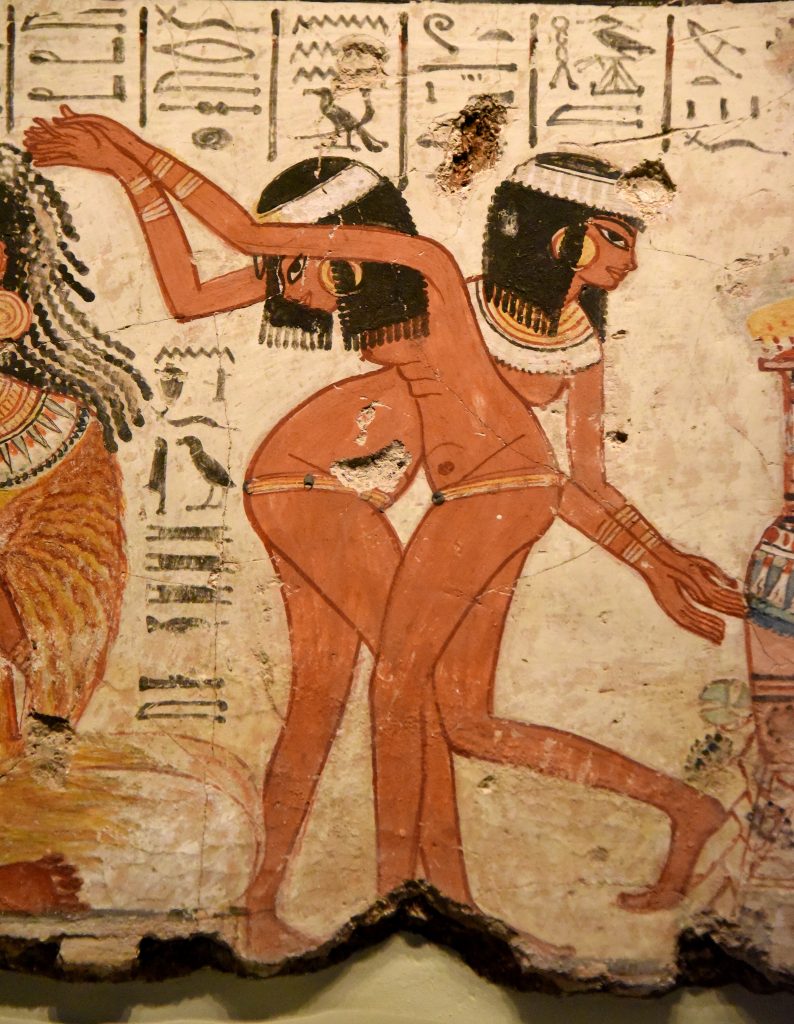

An entire wall of the tomb-chapel shows a feast in honor of Nebamun. Naked serving girls and servants wait on his friends and relatives. Married guests sit in pairs on fine chairs, while the young women turn and talk to each other. This erotic scene of relaxation and wealth is something for Nebamun to enjoy for all eternity. The richly dressed guests are entertained by dancers and musicians, who sit on the ground playing and clapping. The words of their song in honor of Nebamun are written above them: “The earth God has caused his beauty to grow in every body…the channels are filled with water anew, and the land is flooded with love of him.” The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Part of the feast scene. Musicians are playing their instruments. Two naked young girls are dancing while other naked girl (upper register) is serving Nebamun’s guests. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

All the guests wear elaborate linen clothes. The artists have painted the clothes as if it were transparent to show that it is very fine. These elegant sensual dresses fall in loose folds around the guest’ bodies. The lower register depicts sitting women playing their instruments. Acquired by Waddington and Hanbury in Egypt in 1821. Donated to the British Museum by Sir Henry Ellis in 1833. This was the last, eleventh, painting acquired by the British Museum in 1833. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The young men sit on rows of stools, beside a group of young women, who sit on chairs with cushions. Men and women’s skin are painted in different colors; the men are tanned while the women are paler. In one place, the artists altered the drawing of these wooden stools and corrected their first sketches with white paint. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Some of the musicians look out of the paintings showing their faces full-on. This is very unusual in Egyptian art and gives the sense of liveliness to these lower class women, who are less formally drawn than the wealthy guests. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The young dancers are fluidly drawn and are naked apart from their jewellery. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

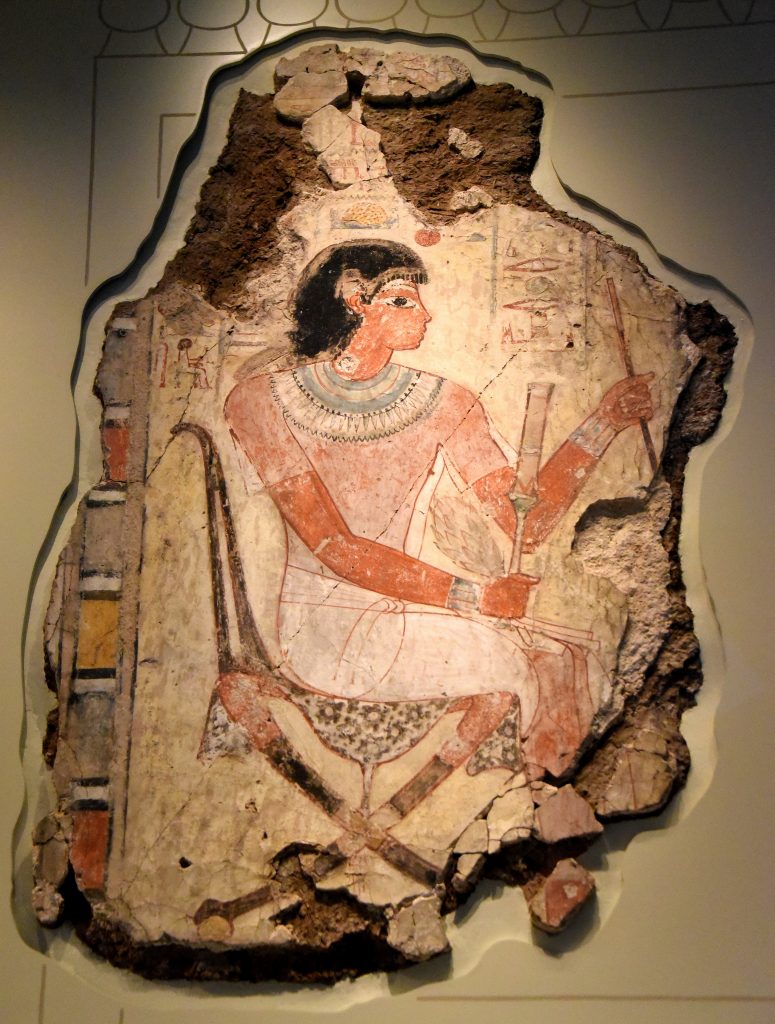

Nebamun viewing his geese and cattle

These 3 paintings are part of a wall showing Nebamun inspecting his geese and cattle. He watches as farmers bring the animals to him; his scribes (secretaries) record the number of animals to him. Hieroglyphs describe the scene and the farmers’ conversation, talking and squabbling among themselves, as they queue up. Nebamun is depicted as a man of wealth and authority, supervising large numbers of servants and animals. Everything is designed to show Nebamun’s prestige; he is shown at a larger scale than other people and is posed formally. Even his skin is painted differently. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Nebamun sits on a chair and inspects his geese and cattle. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

At the left side, a scribe holds a palette pen-box under his arm and presents a roll of papyrus to Nebamun. The scribe is well-dressed and has small rolls of fat on his stomach, indicating his superior position in life. Beside him, are chests for his records and a bag containing his writing equipment . Farmers bow down and make gestures of respect towards Nebamun. The man behind them holds a stick and tells them: “Sit down and don’t speak!”The farmers’ geese are painted as a huge and lively gaggle some pecking the ground and some flapping their wings. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

![The alternating colors and patterns of cattle create a superb sense of animal movement. The artists have omiited some of the cattle's legs to preserve the clarity of thedesign. The herdsman is telling the farmer infornt of him in the queue: "Come on! Get away! Dpn't speak in the presence of the praised one! He detests people talking...Pass on in quite and in order...He knows all affairs, does the scribe and counter of the grain of [Amun], Nebamun]". The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Nebamun tomb-chapel.](http://etc.ancient.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/OSA_5540-1024x613.jpg)

The alternating colors and patterns of cattle create a superb sense of animal movement. The artists have omitted some of the cattle’s legs to preserve the clarity of the design. The herdsman is telling the farmer in front of him in the queue: “Come on! Get away! Don’t speak in the presence of the praised one! He detests people talking…Pass on in quite and in order…He knows all affairs, does the scribe and counter of the grain of [Amun], Neb[amun]”. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The name of the god Amun has been hacked out in this caption. even where it appears in Nebamun’s name. Shortly after Nebamun was buried, King Akhenaten (1352-1336 BCE) had the name of Amun erased from all monuments as part of his religious reforms. This is a zoomed-in part of the right side of the previous image. The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

To draft this article, I depended on the following:

1. The Painted Tomb-Chapel of Nebamun, by R. Parkinson. This is a very wonderful book that tells you each and every thing about these paintings.

2. The British Museum collection online.

3. Personal visits to the British Museum.

These photographs and their captions represent the whole Nebamun’s tomb-chapel paintings in Room 61. This is a virtual cyber-tour! At the end of the day at the British Museum, March 14, 2016, I was very exhausted! After I finished photographing all of the 11 paintings using my Nikon D750 camera, I stood far way, at one of the corners of Room 61, watching visitors as they enter into this room. I observed them for about a quarter of an hour. Some of them passed through the room rapidly, some were taking selfies with the paintings, and some shot the paintings using their phones or digital cameras. None of the visitors spent some time reading the captions and examining the paintings thoroughly. This is understandable, as the Museum is quite large and you have to go here and there rapidly!

Before I left the room, I stood in front of the painting of Nebamun in the marshes. I closed my eyes, and asked the time machine to take me back. Who built the tomb-chapel? Who were the artists who designed and made the paintings? How many people visited the tomb-chapel and what they were doing there? Did Nebamun think, even for a fraction of a second, that his tomb-chapel paintings will be displayed in a country other than his Egypt?

No words can express my sincere gratitude towards the British Museum in London; it has housed, protected, conserved, and displayed this magnificent and stunning world-class Egyptian art. I was with diverse people within this Room 61, many people, of different races and colors, different religions, different citizenship; I was with humanity and ancient history, the spirit of eternity!

Finally, I stood at the room’s door, turned back my face and looked at the paintings for the last time. Through this article, I have successfully put myself on the path of eternity, with Nebamun; I have left a legacy too!