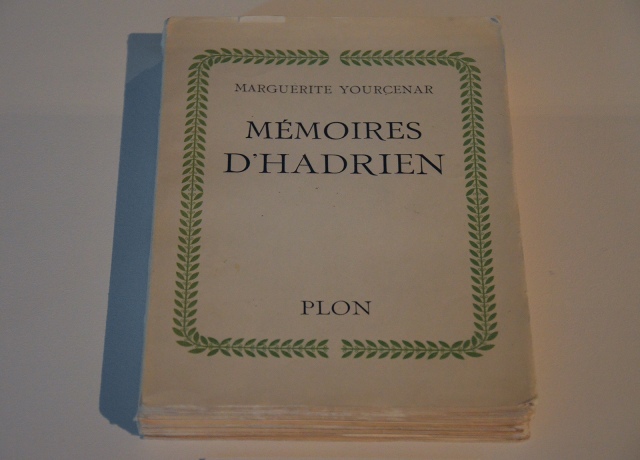

Last year, the Forum Antique de Bavay, located in northern France, hosted a small exhibition devoted to the book Mémoires d’Hadrien (Memoirs of Hadrian).

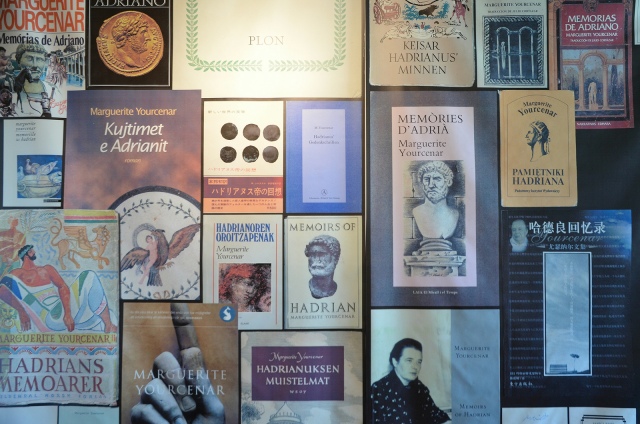

The exhibition sheds light on the genesis of Mémoires d’Hadrien and presents archaeological objects and ancient texts. It provides insight into the meticulous work behind Marguerite Yourcenar’s historic novel, compiling postcards and photographs of works and places relating to her subject, studying all the ancient sources with a passionate and serious enthusiasm. On display are books, manuscripts, statuary, portrait busts, and coins, as well as different artefacts from the time of Hadrian and the Antonines. Fifty works are on loan from the Louvre, the British Museum, Hadrian’s Villa, the Museum Ingres in Montauban, the Gallo-Roman Museum of Lyon and the Musée Saint-Raymond in Toulouse. It is the first exhibition in France about Mémoires d’Hadrien.

The story between Hadrian and Marguerite Yourcenar is a long and fascinating one which lasted some 36 years before Mémoires d’Hadrien finally got published. It begins in 1915 when Yourcenar, as a 12 year old girl, visits the British Museum and sees for the first time the bronze head of Hadrian which had been recovered from the River Tames. A poem, ‘L’Apparition’, probably written when she was 16, features a statue of Antinous in the gardens at Tivoli. But it was not before her visit to Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli in 1924 that the young Marguerite, who was 21 years old at the time, decided to write about the emperor Hadrian.

The writing Mémoires d’Hadrien was not going to be an easy task. Two years after her visit to Tivoli, Yourcenar wrote a dialogue entitled ‘Antinoos’ and submitted it to the publisher Fasquelle. The manuscript was rejected by Fasquelle and destroyed by the author. She resumed her historical researches between 1934 and 1937 while on a trip to the United States. She undertook extensive reading in the libraries of Yale University in order to expand her knowledge of classical antiquity. It was at this time that she started writing the first lines of the manuscript, including the opening scene of the novel when Hadrian’s visit to his physician Hermogenes. When WWII broke out in 1939, she exiled herself to the United States, armed only with some notes made at Yale, a map of the Roman Empire at Trajan’s death and a postcard of the bronze head of Antinous from the Archaeological Museum in Florence. She entered a long period of uncertainty and abandoned her literary ambitions going as far as burning all her notes. Yet fate would dictate otherwise.

On a cold day in January 1949, Youcernar, now aged 46, received a trunk from Switzerland full of personal effects she had left in Europe. The trunk contained lots of family papers, old letters and an accumulation of correspondence with people she had forgotten, most of which ended up in the fireplace. While throwing the letters mechanically into fire, she came upon some pages that started with the line “Mon cher Marc” (My dear Mark). Youcernar recounts in her “Reflections on the Composition of Memoirs of Hadrian”: “I could not recall the name at all. It was several minutes before I remembered that Mark stood here for Marcus Aurelius, and that I had in hand a fragment of the lost manuscript. From that moment there was no question but that this book must be taken up again, whatever the cost.”

This extraordinary chance event marked the beginning of the rewriting of Mémoires d’Hadrien which was finally completed and published in 1951. The novel took the form of a lengthy letter written by the aged and ill Emperor Hadrian to the 17-year-old but already thoughtful Marcus Aurelius. As the book opens, Hadrian is sixty and dying. His life, he says, seems to him “a shapeless mass,” but in this memoir he will try to make some sense of it. To this day the book ranks as one of the finest historical novels ever written and is considered to be among the 100 greatest books of all time.

“Nothing is slower than the true birth of a man.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Through the works exhibited, Hadrian is presented as the philhellene, the builder of many cities, the poet, the political, the hunter, the traveller who spent most of his reign visiting the provinces and the lover. It is with the first page of Memoirs of Hadrian that we enter the exhibition.

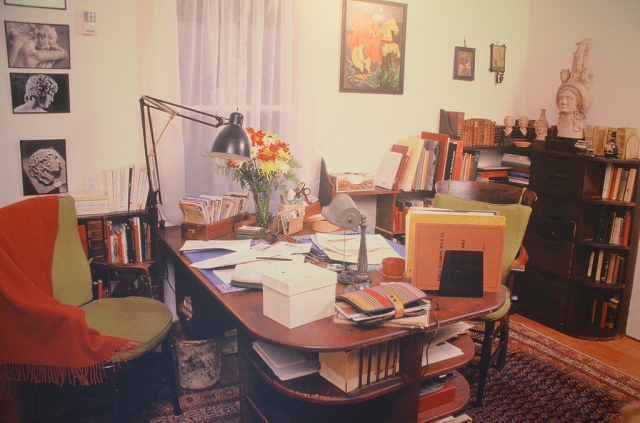

The exhibition is divided into five thematic sections. The first section is devoted to the research and archives of Marguerite Yourcenar. We find ourselves immersed in her office and discover the intensive study done by the author. On display in this section are workbooks in which she amassed documents and photographs related of Hadrian as well as annotated manuscripts.

In the notes appended to the novel, Yourcenar mentions the reading she did prior to painting the emperor’s portrait: “The same night I re-opened two to of the volumes which had also just returned to me, remnants of a library in large part lost. One was Dio Cassius in Henri Estienne’s beautiful printing, and the other a volume of an ordinary edition of Historia Augusta, the two principal sources of Hadrian’s life, purchased at the time that I was intending to write this book.” Image © Carole Raddato.

The second section introduces the visitor to Hadrian’s family and to a man anxious to make his mark on history. Portrait busts of Trajan, his adopted father, of his wife Sabina and of Marcus Aurelius, his adopted grandson, are displayed alongside a portrait of Hadrian from Carthage, a copy of the bronze head from the River Thames and a cameo with portraits of Trajan and his wife Plotina.

“Officially a Roman emperor is said to be born in Rome, but it was in Italica that I was born; it was upon that dry but fertile country that I later superposed so many regions of the world.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

“To build is to elaborate with earth, to put a human mark upon a landscape, modifying it forever thereby; […]”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Hadrian’s great building projects across the empire are perhaps his most enduring legacy; his grand circular mausoleum located on the right bank of the Tiber in Rome, the wall that still snakes across northern England, his vast villa at Tivoli and the Pantheon, one of the best-preserved and most beautiful of all classical buildings.

“My military successes might have earned me enmity from a lesser man than Trajan. But courage was the only language which he grasped at once; it works straight to his heart.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

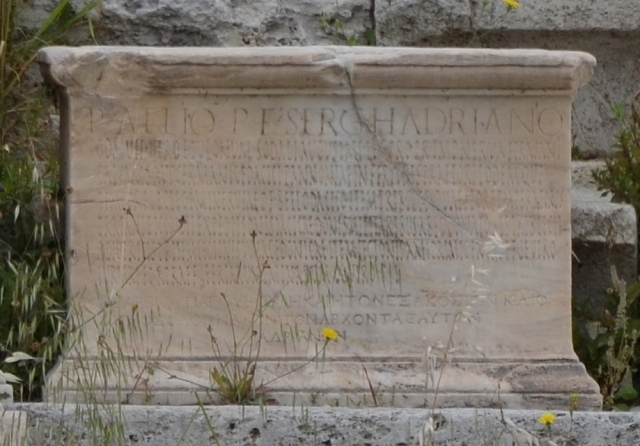

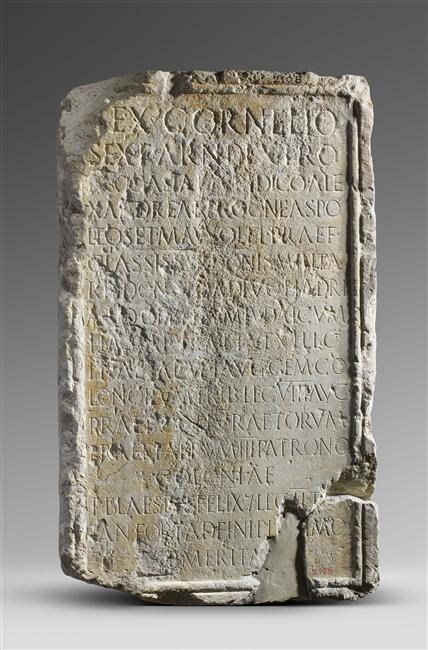

At the age of 14, Hadrian entered the military in Italica. However, he was more interested in going hunting and enjoying other civilian luxuries. Trajan took him back to Rome and Hadrian entered public service in preparation for a senatorial carrier. He began to follow the traditional career of a Roman senator, advancing through a conventional series of posts. A statue base set up in 112 AD in the Theatre of Dionysus in Athens commemorates his whole senatorial career. Hadrian held the Athenian archonship in 111-112 AD and this was the occasion for the setting up of the monument. The career enumerated confirms the description of Hadrian’s career given in the beginning of the Historia Augusta.

Yourcenar, like Hadrian, had a passion for travel and mainly lived abroad, especially in Greece and Italy. In this third section it is the statesman that we discover through his travels across the Empire but also through his strict military discipline and frontier policy. Hadrian was determined to consolidate the Roman Empire’s borders, in the North as well as in the South.

“What was important was that someone should be in opposition to the policy of conquest, envisaging its consequences and the final aim, and should prepare himself, if possible, to repair its errors.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

In the summer of 128 AD, while staying in the legionary base of Lambaesis in the province of Africa (modern-day Algeria), Hadrian observed the soldiers from the Legio III Augusta exercising. After observing each unit, he addressed several groups of soldiers in a speech (aldocutio). A substantial part of the speeches he delivered has survived (see here).

I had to point out to the officers only one slight error, a group of horses left without cover during a feigned attack on open ground; my prefect Cornelianus satisfied me in every respect.

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

In Britannia, Hadrian ordered the construction of a 117 kilometre long wall which led to the production of “souvenir” objects in the likeness of the small enamelled bronze cup (patera) from Amiens.

The Amiens Patera, a bronze bowl with a single long handle found at Amiens. Exhibition: Marguerite Yourcenar et l’empereur Hadrien, une réécriture de l’Antiquité – Bavay (France) Image © Carole Raddato.

The Amiens Patera, is a bronze bowl with a single long handle found in 1979 in Amiens, France (a stopping place for Roman soldiers). It features a representation of Hadrian’s Wall and a list of several Roman forts. The six forts listed on the Amiens Patera are Maia, Aballava, Uxelodunum, Camboglanna, Banna and Aesica.

“Plotinopolis, Hadrianopolis, Antinoopolis, Hadrianotherae. … I have multiplied these human beehives as much as possible. Plumber and mason, engineer and architect preside at the births of cities […].”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

No other Roman emperor travelled as much as Hadrian. He was famed for his endless journeys around the empire and devoted at least half of his reign to the inspection of the provinces. He founded new cities like Plotinopolis in Thrace (named in honour of Trajan’s Empress, Plotina) or Antinoopolis in Egypt (named in honour of Antinous). He also refounded Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina in Judea, the first step towards the Bar Kokbah Jewish revolt. There were several cities named Hadrianopolis, including the modern towns of Edirne, Mersin and Niksar (Turkey) and Dropull (Albania).

Inscription in honour of Sextus Cornelius Dexter, prefect of the Syrian fleet (praefectus classis Syriacae). He was honored by Hadrian during the Jewish Revolt (CIL VIII 8934). Photo © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Hervé Lewandowski.

Hadrian was a great patron of the arts and he especially valued reading. He is reported to have preferred older, more archaic authors; Cato, Ennius and Caelius Antipater rather than Cicero, Virgil and Sallust (Historia Augusta, Hadrian 16.6).

“Poetry transformed me: initiation into death itself will not carry me farther along into another world than does a dusk of Virgil. In later years I came to prefer the roughness of Ennius, so close to the sacred origins of our race, or Lucretius’ bitter wisdom; or to Homer’s noble ease the homely parsimony of Hesiod.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Hadrian wrote an autobiography which was probably in the form of letters to his adopted son and successor Antoninus Pius. Unfortunately this is now lost except for a short excerpt on a papyrus fragment from Egypt. Hadrian also wrote poetry in both Latin and Greek like his poem Animula.

“A new project long occupied me, and has not ceased to do so, namely, the construction of the Odeon, a model library provided with halls for courses and lectures to serve as a center of Greek culture in Rome. I made it less splendid than the new library at Ephesus, built three or four years before, and gave it less grace and elegance than the library of Athens, but I intend to make this foundation a close second to, if not the equal of, the Museum of Alexandria […].”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

“My hunts in Tuscany have helped me as emperor to judge the courage or the resources of high officials; I have chosen or eliminated more than one statesman in this way. In later years, in Bithynia and Cappadocia, I made the great drives for game a pretext for festival, a kind of autumnal triumph in the woods of Asia. But the companion of my last hunts died young, and my taste for these violent pleasures has greatly abated since his departure.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Hadrian was a passionate and excessive hunter. He spent most of his youth in Italica occupied with this pursuit and he continued hunting wherever he went as Emperor. The tondi reused in the Arch of Constantine testified to his devotion to hunting or the creation of the city Hadrianoutherai (Hadrian’s Hunts) in Asia Minor where he had killed a she-bear. Hadrian loved his horse, the gallant Borysthenes whom he honoured with an epigraph for the grave he had built for him. In time of peace, the imagery of Hadrian’s hunts was used as an expression of power and as a demonstration of Hadrian’s virtues.

The exhibition ends with the love story between the emperor and the beautiful young boy from Bithynia. A magnificent colossal bust from the Louvre, the Antinous Mondragone, one of Yourcenar’s favourite images of Antinous, is exhibited alongside a marble head from the Musée Ingres.

Marguerite Yourcenar et l’empereur Hadrien, une réécriture de l’Antiquité

“[…] we felt, nevertheless, that we had gone back into that heroic world where lovers die for each other.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Antinous was likely introduced to Hadrian in 123 AD, before being taken to Italy for a higher education. He had become the favourite of Hadrian by 128 AD, when he was taken on a tour of the Empire as part of Hadrian’s personal retinue. Antinous accompanied Hadrian during his attendance of the annual Eleusinian Mysteries in Athens, and was with him when he killed the Marousian lion in Libya (a poem by the Alexandrian Greek Pankrates describes in epic detail the hunt).

Little is known of Antinous’ life, but Marguerite Yourcenar imagined a shy and reserved Antinous. She described him as provincial and ill-at-ease amongst the imperial court but totally devoted to his lover.

Following his death on the Nile in October 130 AD, Hadrian deified Antinous and founded and organised a cult devoted to his worship that spread throughout the Empire. Hadrian founded the city of Antinopolis close to Antinous’ place of death, which became a cultic centre for the worship of Osiris-Antinous.

“Antinoopolis, dearest of all, born on the site of sorrow, is confined to a narrow band of arid soil between the river and the cliffs.”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

“Little soul, gentle and drifting, guest and companion of my body, now you will dwell below in pallid places, stark and bare; there you will abandon your play of yore. But one moment still, let us gaze together on these familiar shores, on these objects which doubtless we shall not see again….Let us try, if we can, to enter into death with open eyes…”

― Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

Visitor Information

The exhibition “Marguerite Yourcenar et l’empereur Hadrien, une réécriture de l’Antiquité” runs until 30 August 2016 at the Forum Antique de Bavay.

The Roman Forum of Bavay is open every day from 9am to 12pm and from 2pm to 6pm.

Closing: Wednesday and Saturday morning and bank holidays (1st January, 1st May, 1st and 11th November and 25th December).

Annual closing: 1st fortnight of September and 2nd half of January.

All admission tickets include admission to the permanent collection, the archaeological site and the temporary exhibition. A virtual tour of the Forum is also included.

Prices: full 5€; reduced 3€; free for children “under 18”.

Official website: www.forumantique.lenord.fr

Reference:

- Exhibition catalogue: Marguerite Yourcenar et l’empereur Hadrien : Une réecriture de l’Antiquité (in French – buy it on Amazon)

Sources:

- “Marguerite Yourcenar.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. 2004. Encyclopedia.com. 12 May. 2016 <http://www.encyclopedia.com>

- John Bodel, Epigraphic Evidence: Ancient History from Inscriptions. London: Routledge, 2001 (p. 89)