On October 4, 1961, the Sulaymaniyah Museum received several artifacts, part of the so-called “Nimrud Ivories.” The package was sent from the Iraqi Museum at Baghdad and authorized personnel delivered it. The accompanying documents were written in the Arabic language and very briefly and superficially describe each and every item. I was able to get access to the archives of these ivories at the archives department of the Sulaymaniyah Museum; no details of their excavation history, travel journey, reparation work, or exhibition are available. All these details can be found at the Iraqi Museum, of course.

On November 27, 2014, I was shooting photos of some Assyrian wall reliefs from the Northwest palace of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu; Biblical Calah). Two large display cases next to me drew my attention; these housed the Nimrud Ivories. I spoke to Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, the director of the museum, about them. I told him that the British Museum had successfully gathered £1,170,000 (through donation) in order to acquire a large number of Nimrud Ivories.

“Why not let the world see our collection of these ivories?” I said to him. “Scientists, archaeologists, post-graduate and undergraduate archaeology students, and the public around the world have not heard of the Sulaymaniyah Museum and have no idea that we own some of the Nimrud Ivories,” I added. He said, “What do you suggest?” I replied, “Please let me shoot photos of each and every item and then provide me with some details!” He immediately responded, “You can approach and shoot photos of each and every item, as you like!” He asked Ms. Niyan Saber to help me. She is one of the museum’s archaeologists, who has an extreme interest in the Nimrud Ivories and who participated in their restoration work in 2012.

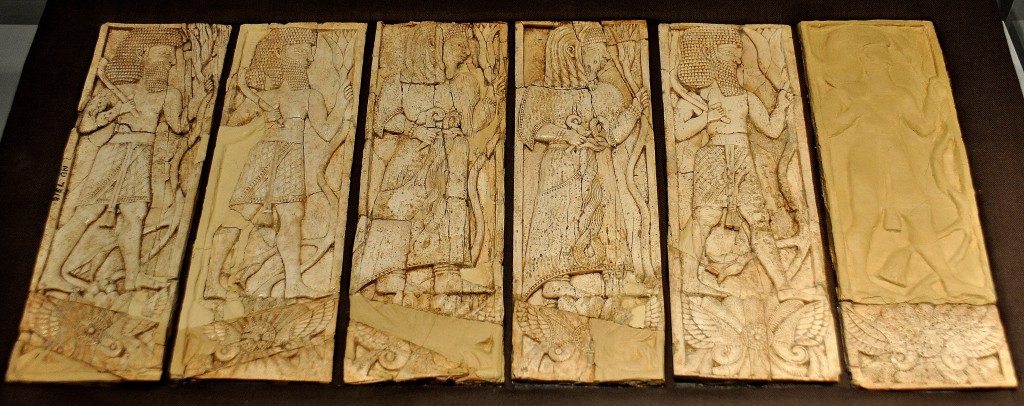

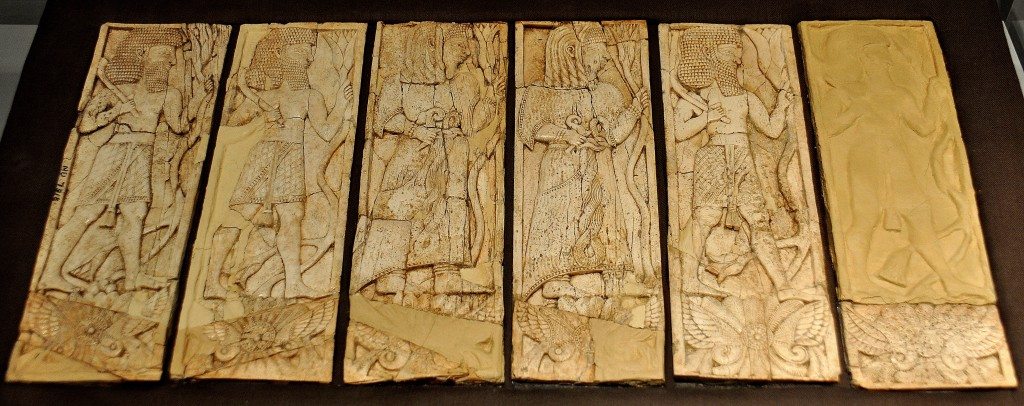

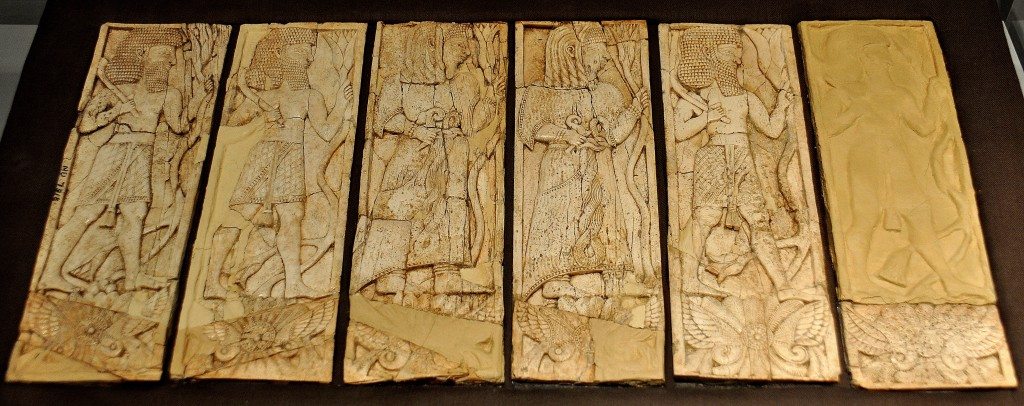

This ivory plaque depicts six Assyrian worshippers in procession in six vertical rectangles. Note the details of their dresses. The men are bare-chested and wear kilts, while the women wear a full dress. Both wear impressive belts. Four men and two women stand on what appears to be the symbol of the god Ashur. The plaque was part of a furniture inlay. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

I, with the great help of Ms. Niyan, took pictures of the ivories. We chatted a lot meanwhile. She helped a lot; she described each and every item and showed me which areas had cracked and then been repaired. An American team did the restoration work in 2012. I was afraid to touch and feel these ivories; they were very delicate!

This collection was excavated by Sir Max Mallowan between 1949-1963 CE at the ancient city of Nimrud. The work was led by the British Institute for the Study of Iraq (at that time it was named the British School of Archaeology).

Mr. Hashim said, “As you may see, Osama, some of the ivories were stamped with the letters ‘ND’ and a number (this reflects their excavation number when they were found at Nimrud). Then, some of them were stamped with ‘MM’ (or م م in Arabic), which means that these ivories were next transferred to the Mosul Museum. The stamp of the Iraqi Museum (‘IM’) is seen on all ivories and is very clearly highlighted. Finally, we were given some of the ivories in the year 1961 CE, when the museum was very new and the ivories held our stamp, ‘SM’ or س م!” Finally he said, “Osama, please feel free to tell the world about this very inaccessible collection of ours.”

Iraq is a war area, and the current turbulent circumstances prevent foreigners, tourists, and Western scientists and archaeologists from reaching us. My intention is to tell you about this collection of ivories at the Sulaymaniyah Museum in Iraqi Kurdistan. I will ask my dear friends, Joshua Mark and Mark Cartwright to draft a detailed article about the archaeology of the Nimrud Ivories; I hope they will accept!

Many thanks go to Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, the Director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum, and archaeologist Niyan Saber, for their kind help. A special gratitude goes to the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan; without their generosity and continuous funding, this collection would have not been repaired, and without their permission, this set of photos would have not been seen by the world.

A total of 29 items were photographed. This number represents the whole collection. If you ever visit the Sulaymaniyah Museum, don’t forget to go to the end of the left wing hall and see the Nimrud Ivories!

Woman at the Window

“Woman at the window” or “the lady of the window” is one of the most famous scenes in Phoenician ivory carving. The plaque shows a woman who looks out of a window, thought to be a sacred prostitute linked to the goddess Astarte or Ishtar. However, the exact significance of the scene is still unknown. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). The Museum houses 3 similar ivory plaques. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Egyptians

This carved ivory plaque depicts a standing man with an Egyptian hairstyle. The man has two wings and holds a snake. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Carved ivory plaque of an Egyptian-looking woman. Note the black burn marks. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

An Egyptian-looking man holds a lotus flower on a long stalk. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A standing man with an Egyptian appearance holds branches of a lotus tree. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Lotus Branches

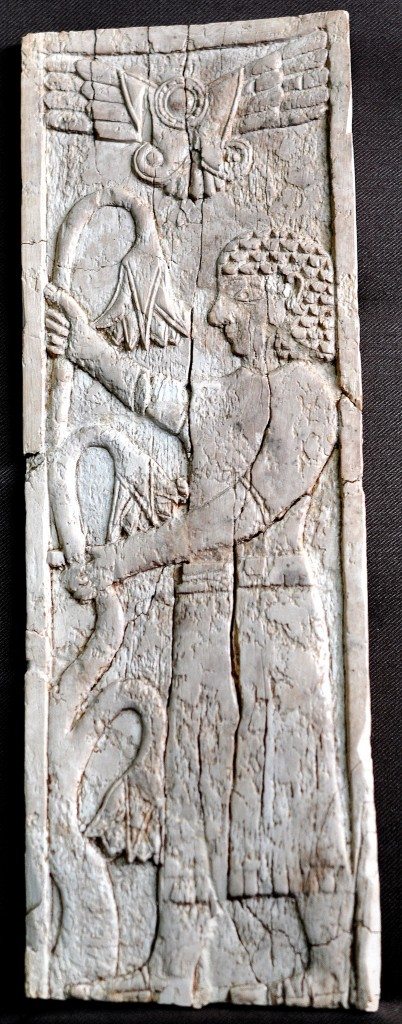

Another ivory carving of a man holding lotus branches. Note the winged ring of the god Ashur at the top. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

In this carved ivory, we can see a person (man or woman; Egyptian as others?) sitting on a chair and holding branches of lotus tree. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A fragment of a carved ivory plaque. On the left, the arm of a person holds a branch of lotus. Part of his wing appears. On the right, part of a wing of another person can be seen. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Phoenician Style Animals

Partially damaged ivory plaque which depicts a two-winged four-legged animals. The animals are striding, back to back. Cloisonne design with Phoenician style. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A Phoenician sphinx, partially broken. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Assyrian Worshippers

This ivory plaque depicts six Assyrian worshippers in procession in six vertical rectangles. Note the details of their dresses. The men are bare-chested and wear kilts, while the women wear a full dress. Both wear impressive belts. Four men and two women stand on what appears to be the symbol of the god Ashur. The plaque was part of a furniture inlay. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The God Ashur

Carved ivory plaque of wings of the god Ashur. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

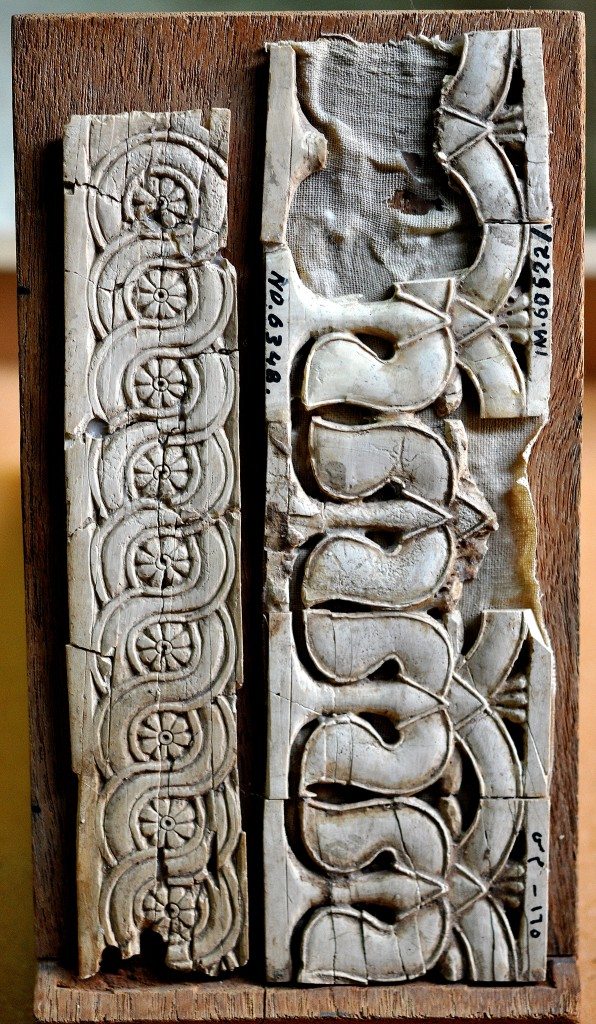

Ornaments

Carved ivory plaque that depicts plant decoration. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Winged Person

The lower half of the body of a person with his wing appears in this broken ivory plaque. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Supine Bull

An exquisitely carved plaque of a supine bull. Note the black burn mark. Probably this was part of a group which once supported an ivory tray. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Another carved plaque of a supine bull. Probably this was part of a group which once supported an ivory tray. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Tiny Ivory Mask

This mask-like ivory is about 1 cm in diameter. Note that the left eye socket was inlaid with lapis lazuli! Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Burned Ivory Head

A burned ivory head of a man or woman. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). It is about 1 cm in maximum diameter. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Rosettes

Rosette. Note the Iraqi Museum acquisition number. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

A panel of rosettes; note the surviving colors. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Man Approaching Trees

A horizontal partially restored burned plaque. It depicts an animal approaching small trees. The scene repeats itself regularly; therefore, I shot the left side only because it is very small. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Ivory Items

Various ivory items. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Head on a Shaft

A carved ivory depicting a human head on a shaft. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Animal Fragments

In this carved ivory plaque, the legs and eagle-like feet appear. This most probably represents an Apkallu (sage). Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

In this broken ivory plaque, the tail and the hind legs of a four-legged animal appear. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The thighs, knees, and upper part of the legs of a creature (animal?) can be seen in this broken ivory plaque. The back of the plaque is hollow, and it seems that it fits something. In this broken ivory plaque, the tail and the hind legs of a four-legged animal appear. Neo-Assyrian period, 9th-7th centuries BCE. From Nimrud, Mesopotamia, Iraq. (The Sulaimaniyah Museum, Iraq). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.