When you visit the Sunken Cities exhibition at the British Museum, you feel as if you are diving beneath the waters of the Nile River. You pass through a corridor illuminated by blue light and into galleries painted in a navy blue. There are dappled lighting effects to imitate water – it’s a wonder they don’t hand out snorkels to complete the illusion. The idea works, however, and you feel just like the archaeologists whose work has formed the basis for this display. It is as if you are discovering a world that has been hidden for more than a thousand years.

The two titular sunken cities, Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus, originally stood at the mouth of the Nile and sank in the 8th century CE. Before the foundation of Alexandria, Thonis-Heracleion had been the port of entry into Egypt, welcoming ships from all over the Hellenic world and providing access to the major cities of Naukratis (the first Greek settlement in Egypt) and Memphis (the capital). The exhibition boasts that 69 ships and 700 anchors were found, giving us an idea of the scale of naval activity in this place. Its neighbour city, Canopus, was directly to the east and connected to Thonis-Heracleion by a canal. The legend goes that Canopus was named after Menelaus’ helmsman, who was bitten by a viper and died there.

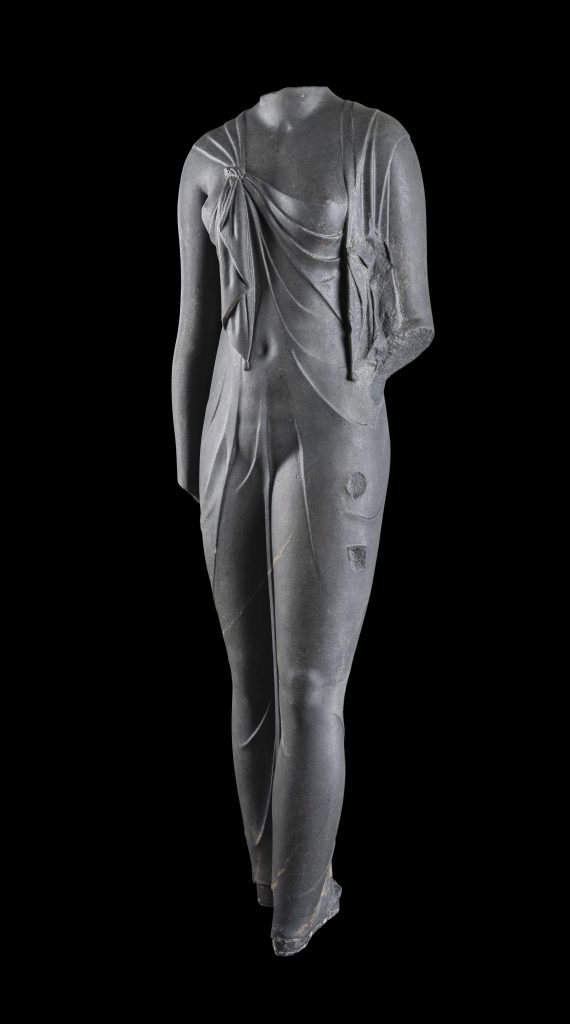

The blend of Hellenic and Egyptian cultures is what comes across most strongly in this exhibition. Focusing on the Ptolemaic period, it is fascinating to see how Egypt’s Greek pharaohs sought to bring their people together. The Egyptian gods found counterparts in the Greek pantheon (even if the Greeks were decidedly bemused by the Egyptian’s worship of animals) and temples celebrated their joint identities. Thonis-Heracleion, for instance, is said to have had a famous temple to Hercules, who was thought to be the Egyptian god Horus. Amun, the bestower of kingship, was Zeus, Osiris was Dionysus, and Isis was Aphrodite. One of the stand-out pieces of the exhibition is a statue of Arsinoe, daughter of Ptolemy I. The smooth, dark stone and striding position is typical of Egyptian sculpture, while her transparent garment and sensual flesh bears a more typically Greek aesthetic. Even without a head, it is mesmerising to look at, bathed in a cool blue light and framed by a gap in the wall between the galleries.

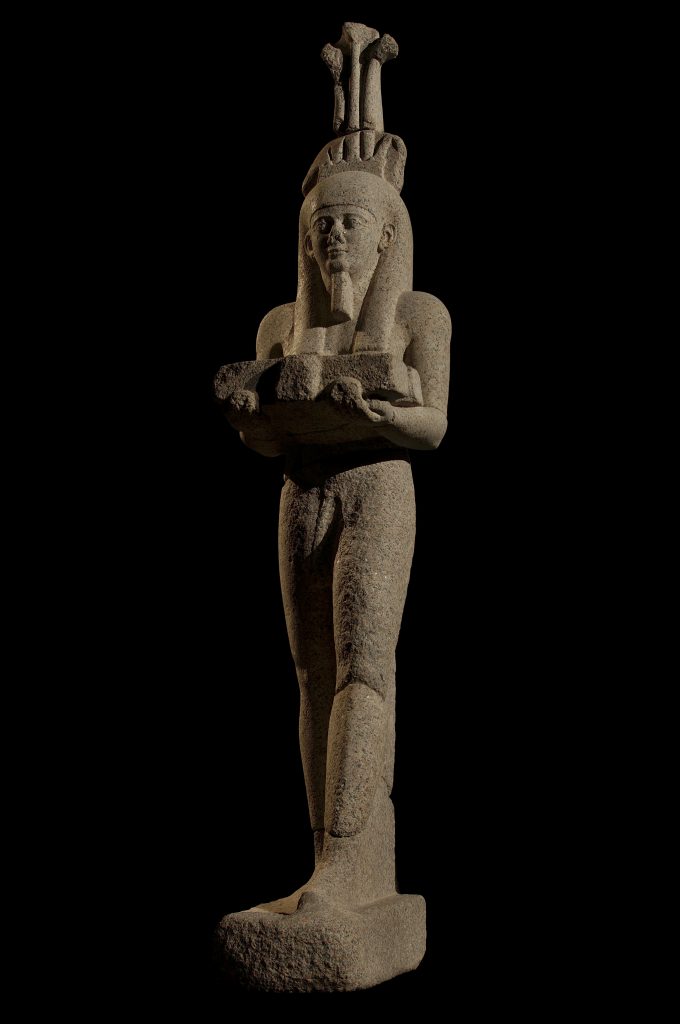

Other jaw-dropping pieces at the Sunken Cities exhibition include the colossal statue of Hapy, the god of the Nile flood, who was originally placed at the entrance to the temple of Hercules. He is hidden around a corner as you first enter the exhibit to elicit a sharp gasp when you do finally see him. There are also statues of Osiris, one in stone, one made of grain, that would sail along the canal during the annual Mysteries of Osiris to celebrate the renewal of the earth each year. Further in, you’ll come across an enormous inscribed stone, featuring both Egyptian and Greek (similar to the Rosetta Stone), which demonstrates the bilingualism the communities in these cities. Elsewhere there are exquisite canopic jars, a frighteningly life-like statue of the bull god, Osiris-Apis (Serapis in Greek), ritual ladles and jars – the list goes on and on.

Photo by Christoph Gerigk; © Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation.

It takes hours to go around the whole exhibition and even then, there is more than you can ever hope to really take in. But out of the blur of material, you really get a sense of a world whose horizons were open. These Egyptian cities were clearly proud of their ancient traditions yet foreign ideas had a place with them too. Whether the peoples of this mixed kingdom blended well is impossible to know from Sunken Cities’ exhibition, but the potential beauty of their integration is clear to see.