Tetradrachm with Apollo from Leontini, 435-430 BCE. The American Numismatic Society (1997.9.121). Greek adult men would ritually cut their hair and grow a beard, but Apollo, whose long hair is often described as golden, defines the ultimate appearance of an ephebe, a beardless adolescent. Apollo wears a wreath of leaves from a laurel, a tree associated with the god’s oracle at Delphi.

From the dawn of civilization to the present day, human hair has seldom been worn in its natural state. Whether cut, shorn, curled, straightened, braided, beaded, worn in an upsweep or down to the knees, adorned with pins, combs, bows, garlands, extensions, and other accoutrements, hairstyles had the power to reflect societal norms. In antiquity, ancient hairstyles and their depictions did not only delineate wealth and social status, or divine and mythological iconography; they were also tied to rites of passage and religious rituals. Hair in the Classical World, now on view at the Bellarmine Museum of Art (BMA) in Fairfield CT, is the first exhibition of its kind in the United States to present some 33 objects pertaining to hair from the Bronze Age to Late Antiquity (1500 BCE-600 CE). The exhibition takes the visitor on a rich cultural journey through ancient Greece, Cyprus, and Rome, in an examination of ancient hairstyles through three thematic lenses: “Arrangement and Adornment”; “Rituals and Rites of Passage”; and “Divine and Royal Iconography.”

In this exclusive 2015 holiday season interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Dr. Katherine Schwab and Dr. Marice Rose, art history professors in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at Fairfield University, who teamed up to co-curate this unprecedented exhibition.

JW: Dr. Katherine A. Schwab and Dr. Marice E. Rose, I bid you both a warm welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia, and I thank you for speaking to me about Hair in the Classical World.

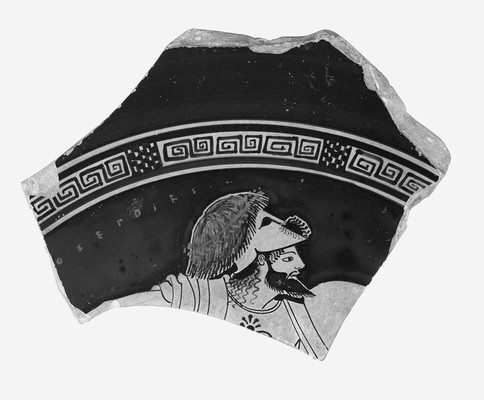

Attic Red-Figured Cup or Bowl Fragment with Bearded Warrior Wearing Scalp of Enemy on Helmet, 500-490 BCE. Attributed to Onesimos as painter (active ca. 505-480 BCE). Signed by Euphronios as potter (active 520-470 BCE). The J. Paul Getty Museum (86.AE.311).

This exhibition, the first ever in the US, investigates the ways in which hair reflected ancient societal norms, and signaled wealth, social status, and even divine prominence. Would you say our modern conceptions of hair have changed significantly since the time of the ancient Greeks and Romans? To what extent have things remained the same given the lasting legacy of ancient Greek aesthetics in the Western world?

KS: Thank you, we are delighted to discuss the exhibition with you, James. In many ways our modern idea of hairstyles is quite different from antiquity because we do not have specific age-related hairstyles to mark rites of passage and significant life events. We do not ritually cut hair to dedicate it here in the US, for example, but these traditions are old and enduring elsewhere. Indian and Hindu traditions include ritual hair cutting today. The beauty of ancient hairstyles and the creative approaches used especially by women in Greece and Rome certainly does sound familiar in our modern world. Individuality, even within societal expectations, was as prevalent then as it is now.

MR: Thank you, it is a pleasure, James. I think conceptions of hair, in terms of its qualities of communicating personal aspects of an individual (gender, age, status, even mental health) and aspects of the culture he or she belongs to, have remained consistent. We have a greater range of clothing choices today, so in antiquity hair was even more important as a bearer of meaning.

Mask from a Cavalry Helmet from Asia Minor, 75-125 CE. The J. Paul Getty Museum (72.AB.105). This mask was worn by a male soldier, but a Roman man would not have worn such long, carefully curled hair. Masks like this may also have been worn by soldiers in contests that re-enacted scenes of Greek myth and history.

JW: We say that “clothes make the man” in English, but could we say that “hair makes the man” — or woman — when speaking about the ancient Cypriots, Greeks, or Romans?

KS: The research for this exhibition brought out the high level of importance ancient hairstyles conveyed in Greece and Rome. An example is the Caryatids from the South Porch of the Erechtheion on the Athenian Acropolis. Long fishtail braids down the back, corkscrew curls from behind the ears, and additional braids wrapped around the head — this combination is unique and distinguishes these maidens who lead a religious procession. Some of the Cypriot male heads have densely textured hair pulled from the crown by a wreath only to spring into thick curls framing the face. Their vitality is evident not only in the facial expression but in the ancient hairstyles they wear. Hair arrangements were intentional and could become closely associated with famous individuals, such as Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE). Adapting his hairstyle carried with it his achievements. The same held true for several of the Roman Empresses, such as Syrian-born Julia Domna (170-217 CE), wife of Emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE). Her distinctive hairstyle became popular enough for dolls to be made with similar hair arrangements.

MR: Yes, definitely! This is true for women of course too. For example, Roman emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty imitated Augustus’ bangs and tousled hair on the forehead to show their connection to him and his successful rule, while Augustus himself was recalling the hair of Alexander the Great. We also have a portrait head in the exhibition, lent by the Yale University Art Gallery, of a girl wearing a style made famous by Augustus’ wife, Livia (58 BCE-29 CE). She has a forehead roll (nodus) and bun, linked by a thin braid. The style would have communicated that this girl would become an ideal wife and mother, like Livia herself. This popular style’s careful control of the hair was a purposeful part of its message of morality and restraint.

10 Drachm (decadrachm) with Arethusa from Syracuse, 405-400 BCE. The American Numismatic Society (1964.79.21). Arethusa’s hair is gathered in an ampyx, a leather or metal band just above her forehead, which is connected to a large open-work hairnet filled with her long hair. This Arethusa shows richly textured, curly hair, with short loose ends projecting outward along the top of her head along with the inscription ΣΥΡΑΚΟΣΙΟ (Syracuse). The hairnet shows long locks of hair in each section, with surfaces now partly worn, separated by small discs decorating the interstices of the net.

The beauty of ancient hairstyles and the creative approaches used especially by women in ancient Greece and Rome certainly does sound familiar in our world today. Individuality, even within societal expectations, was as prevalent then as it is now.”

JW: Ancient hairstyles and accessories could reach a wide audience through the circulation of coins, which presented a clear and formal appearance to a vast public (however idealistic it might have been). Could you contextualize the ways in which hair was an expressive vehicle for the conveyance of power and personal image via coinage?

KS: Greek and Roman coins have been excavated from Spain to India, a testimony to the movement of ideas and goods across the vast network of trade routes. If the coin was still in good condition, the portrait would have been visible and in contention to shape local fashions. Successors to Alexander the Great frequently included an image of Alexander on their own coinage. This sustained use of selective images would have made a strong impression.

Hairpin with Eros from Dura-Europos, ca. 165-256 CE. Yale University Art Gallery (1938.862). Straight hairpins with miniature sculptures on the ends have been found all over the Roman Empire. They were used to hold a tight bun or twist in place, or as a hair ornament. These tiny sculptures would have been seen only by people close to the woman wearing them. Hairpins with women wearing fashionable hairstyles resembled miniature portraits of the wearer herself.

MR: A very good question, as coins are some of our best evidence for the ancient hairstyles of Roman emperors and empresses. As to how influential they would have been…I am not a numismatist, but just on a practical level the coins are very small; the detail of the ones in the exhibit are exquisite, but they are almost mint examples — as we know, over time, details would rub off. I think portrait statues and reliefs, just like actual high-status men and women being seen wearing the styles, may have conveyed the messages more effectively.

JW: Hair in the Classical World includes an evocative section with objects from “cultural crossroads,” like Cyprus, the city of Dura-Europos in what is present-day Syria, and the city of Syracuse on the island of Sicily. How did the transmission of portable objects through international trade influence ancient hairstyles and personal adornment? Could you provide some specific examples.

KS: Dr. Rose provides a very good response to your question. I can only add that this is an area of research worth exploring further in case the archaeological record preserves examples as documentation.

MR: The exhibit contains eight objects from Cyprus from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Cesnola Collection. Cyprus, legendary birthplace of Aphrodite, had rich copper deposits (Cyprus comes from the Greek word for copper, kupros) and was a valuable location for trade and military strategy. Its art combines native Cypriot forms and those drawn from the art of immigrants, trade partners, and conquerors. The island’s especially close ties to Greece mean that the styles most often resemble ancient Greek art, although occupation by Egypt and Persia also had an influence.

Hairnet with Medallion of a Maenad, ca. 200-150 BCE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Gift of Norbert Schimmel, 1987 (1987.220). The luxurious nature of this gold hairnet, or kekryphalos, which would have been owned by a woman of high status, attests to the wealth of the Greek Hellenistic world. A substantial amount of hair would have been required to secure this complex and expensive accessory at the back of the head.

We have two examples of Cypriot male heads wearing wreaths, which comes from Greek culture; gods and goddesses in art wear leafy wreaths as hair accessories, as do mortals engaged in sacred rituals or events. Wreaths were worn at festivals, initiations, weddings, and funerals. They were awarded to winners of athletic competitions, which took place in religious sanctuaries. For important occasions or for royalty, they were crafted in gold and silver. What is different in Cyprus is that the wreaths often include flowers. These might be linked to worship of the Great Goddess of Cyprus, an ancient fertility deity who became assimilated with Aphrodite.

JW: Hair in the Classical World showcases various accouterments, including an ancient hairnet with a medallion, in addition to a number of statuettes, coins, masks, and Attic cups.

Which of the objects on display are the most unique or unusual in your opinion? Have any attracted considerable attention on the part of visitors to the Bellarmine Museum of Art (BMA)?

Statuette of a Running Gorgon, 540 BCE. We see Medusa before Perseus reaches her: A Greek female in the sixth century BCE wearing long hair usually represented a maiden, which was Medusa’s previous status. Here she has abundant long textured hair, both sinuous and segmented to describe wavy texture. In later Greek art, her hair will appear as intertwined snakes coiling and writhing across her head.

KS: I think visitors have looked very closely at the coins and sculptures, but also the images we have included as vinyl wall photographs such as the one of the hairnet. In general, the response has been one of surprise at the focus and importance of hair in antiquity. Some of the very elegant enhancements to ancient hairstyles, such as the hair pins Dr. Rose describes, the Hellenistic gold bun holder, and the late-fifth century BCE silver coin from Syracuse all reveal elaborate accessories to transform hair arrangements from practical into luxurious and even sensual. As for unique or unusual, the Hellenistic bun holder is rare, one of a few known. You have to wonder who wore it (a queen?), how much hair was required to fill it, and the weight of the gold.

MR: I like the Cypriot sculpted heads because to my knowledge their hair has never been examined closely before, so one looks at them from a completely new perspective. I am drawn also to the hairpins with the tiny sculptures on the ends, and the idea that almost 2000 years ago women actually wore these in their hair after dipping them in perfume.

Head of a Cypriot Man, mid-fifth century BCE. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cesnola Collection. Purchased by subscription, 1874–76 (74.51.2826). Gods and goddesses in art wear leafy wreaths as hair accessories, as do mortals engaged in sacred rituals or events. Wreaths were worn at festivals, initiations, weddings, and funerals. They were awarded to winners of athletic competitions, which took place in religious sanctuaries. For important occasions or for royalty, they were crafted in gold and silver. Later, in the Roman Empire, military victors wore them and wreaths became symbols of government authority.

JW: Precisely because it is so resonant of socio-cultural identity, hair is curious but fulfilling lens through which to view antiquity. That being acknowledged, I suspect this was a challenging exhibition to organize and assemble.

What was the catalyst behind this exhibition, and which challenges did you face in organizing such an compelling show?

KS: The catalyst was the 2009 Caryatid Hairstyling Project in which we recreated the six ancient hairstyles. Before this we did not know if they were based in reality or creative imagination. The project, with six student models, proved to be a watershed. We made a short film of the project which has been screened in Athens four times, also in Japan, Italy, and of course here in the US. Interest in the project kept growing which led us to think about a broader theme, Hair in the Classical World, and how we could explore hairstyles through different cultures and time periods.

As any museum curator will tell you, the labels require brevity, information to hold a visitor walking by, and the need to avoid jargon. Condensing our research and information into 50 words was a great preoccupation as we prepared the installation.

MR: As for the challenges, Dr. Schwab is absolutely correct. The only challenge that comes to mind was keeping the wall labels short and concise (and therefore readable); volumes could be written on some of the topics and themes the exhibit highlights.

JW: I have learned so much about the place of hairstyles in Greco-Roman art and culture through our interview! Thank you both for speaking with me about a truly exceptional exhibition. I wish you both the best of luck and many happy adventures in research!

KS: Thank you, James, we are delighted to have this opportunity to discuss the exhibition with you!

MR: Thank you very much James, we are thrilled to share our thoughts and introduce the show to AHE’s audience!

Hair in the Classical World will remain at the Bellarmine Museum of Art (BMA) at Fairfield University in Fairfield, CT until December 18, 2015. Click here to download the Cuseum app for the Hair in the Classical World exhibition, which contains extended label information and an audio tour of select objects. Additionally, please watch the video below in which Dr. Marice Rose and Dr. Katherine Schwab take you on a tour of the exhibition’s highlights.

Dr. Marice Rose is Associate Professor of Art History at Fairfield University, where she is Director of the Art History and Studio Art programs. She is co-editor, with Alison Poe, of the collected volume Receptions of Antiquity, Constructions of Gender in European Art, 1300-1600 (Brill, 2015). Her research, published in journals such as Woman’s Art Journal, New England Classical Journal, Art Education, and The International Journal of the Classical Tradition, focuses on images of women and slaves in late Roman domestic decoration, as well as on classical reception and art history pedagogy. Her chapter on the stone finds from the Palatine East excavation in Rome is included in Palatine East: Excavations of the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma and the American Academy in Rome, Volume 2 (2014). Dr. Rose holds a PhD in Art History from Rutgers University, and a BA in French and Art History from Fairfield University. In addition to the Hair in the Classical World exhibition, she has collaborated with Katherine Schwab on an article on fishtail braids in ancient Greece and today for Catwalk: The Journal of Fashion, Beauty, and Style and also on a forthcoming chapter in the Berg Cultural History of Hair volume on Antiquity.

Dr. Marice Rose is Associate Professor of Art History at Fairfield University, where she is Director of the Art History and Studio Art programs. She is co-editor, with Alison Poe, of the collected volume Receptions of Antiquity, Constructions of Gender in European Art, 1300-1600 (Brill, 2015). Her research, published in journals such as Woman’s Art Journal, New England Classical Journal, Art Education, and The International Journal of the Classical Tradition, focuses on images of women and slaves in late Roman domestic decoration, as well as on classical reception and art history pedagogy. Her chapter on the stone finds from the Palatine East excavation in Rome is included in Palatine East: Excavations of the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma and the American Academy in Rome, Volume 2 (2014). Dr. Rose holds a PhD in Art History from Rutgers University, and a BA in French and Art History from Fairfield University. In addition to the Hair in the Classical World exhibition, she has collaborated with Katherine Schwab on an article on fishtail braids in ancient Greece and today for Catwalk: The Journal of Fashion, Beauty, and Style and also on a forthcoming chapter in the Berg Cultural History of Hair volume on Antiquity.

Dr. Katherine Schwab received her BA from Scripps College, her MA. from Southern Methodist University, and her PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Dr. Schwab joined the faculty at Fairfield University in 1988 where she is both Professor of Art History in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts and Curator of the Plaster Cast Collection at the Bellarmine Museum of Art. The plaster cast collection includes gifts from the Acropolis Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, the Slater Museum, gifts and long-term loans from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as gifts from individuals. Dr. Schwab has been awarded three separate fellowships (both pre- and post-doctoral) by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in addition to the Robert E. Wall Award at Fairfield, as well as other honors and grants in support of her research on the Parthenon Metopes, the 2009 Caryatid Hairstyling Project, and restoration work on the plaster cast collection. Grayscale scans of her research drawings are on permanent display in the Parthenon Gallery of the new Acropolis Museum in Athens, Greece. Her publications include several book chapters, journal articles and, most recently, exhibiting her original Parthenon drawings, An Archaeologist’s Eye: The Parthenon Drawings of Katherine A. Schwab. The exhibition launched at the Consulate General of Greece in NYC in January 2014, and has traveled to the Greek Embassy in Washington, D.C., the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia, the Lied Art Gallery at Creighton University, the Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University. Future venues include the Timken Museum of Art in San Diego, the Nashville Parthenon, and the Forsyth Gallery at Texas A & M University. With her colleague Dr. Marice Rose, she has co-authored, “Fishtail Braids and the Caryatid Hairstyling Project: Fashion Today and in Ancient Athens,” Catwalk: the Journal of Fashion, Beauty and Style (2015), and co-curated, Hair in the Classical World, at the Bellarmine Museum of Art, Fairfield University (October 7-December 18, 2015).

Dr. Katherine Schwab received her BA from Scripps College, her MA. from Southern Methodist University, and her PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Dr. Schwab joined the faculty at Fairfield University in 1988 where she is both Professor of Art History in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts and Curator of the Plaster Cast Collection at the Bellarmine Museum of Art. The plaster cast collection includes gifts from the Acropolis Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, the Slater Museum, gifts and long-term loans from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as gifts from individuals. Dr. Schwab has been awarded three separate fellowships (both pre- and post-doctoral) by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in addition to the Robert E. Wall Award at Fairfield, as well as other honors and grants in support of her research on the Parthenon Metopes, the 2009 Caryatid Hairstyling Project, and restoration work on the plaster cast collection. Grayscale scans of her research drawings are on permanent display in the Parthenon Gallery of the new Acropolis Museum in Athens, Greece. Her publications include several book chapters, journal articles and, most recently, exhibiting her original Parthenon drawings, An Archaeologist’s Eye: The Parthenon Drawings of Katherine A. Schwab. The exhibition launched at the Consulate General of Greece in NYC in January 2014, and has traveled to the Greek Embassy in Washington, D.C., the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia, the Lied Art Gallery at Creighton University, the Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University. Future venues include the Timken Museum of Art in San Diego, the Nashville Parthenon, and the Forsyth Gallery at Texas A & M University. With her colleague Dr. Marice Rose, she has co-authored, “Fishtail Braids and the Caryatid Hairstyling Project: Fashion Today and in Ancient Athens,” Catwalk: the Journal of Fashion, Beauty and Style (2015), and co-curated, Hair in the Classical World, at the Bellarmine Museum of Art, Fairfield University (October 7-December 18, 2015).

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Bellarmine Museum of Art (BMA) at Fairfield University have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Special thanks is given to Ms. Carey Mack Weber, Museum and Collections Manager at the Bellarmine Museum of Art (BMA), for her role in helping make this interview possible. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.