The Six Dynasties period from the third to sixth centuries CE was one of the most dynamic periods in Chinese art history, akin to the European Renaissance in the impact it had on artistic creativity and the celebration of individual expression. Art in a Time of Chaos: Masterworks from Six Dynasties China, 3rd-6th Centuries, now on show at the China Institute in New York, New York, situates these innovations and achievements from both the Southern and Northern Dynasties across four major disciplines: Ceramics, sculpture, calligraphy, and painting. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Ms. Willow Weilan Hai, Director of the China Institute Gallery, about the exhibition.

JW: Director Willow Weilan Hai, thank you for speaking with me about Art in a Time of Chaos: Masterworks from Six Dynasties China, 3rd-6th Centuries.

For those of us less familiar with the Six Dynasties interim, could you tell us why this period is a defining one in Chinese history? I know from historiography that this era is often compared to the European Renaissance in terms of the impact it had on artistic creativity and innovation.

WWH: Indeed, there are many parallels between the European Renaissance and the Six Dynasties period in China. Despite a prolonged period of political chaos, the Six Dynasties’ achievements in art, literature, music, philosophy, science, and even mathematics are remarkable. (For example, Chinese mathematicians discovered Pi or “π” during this era.) Art became an independent form of expression, which led to the development of the later schools of figure painting and landscape painting. Calligraphy, as an art, was standardized in this time too. New concepts and theories are established in this period, guided in turn by the Six Principles of Chinese Painting by Xie He (479-502 CE). Gu Kaizhi (348-409 CE), another famous artist, greatly influenced Chinese art for more than thousand years with his beautiful figure paintings.

This was an era marked by the respect of nature, the praise of individualism, and the encouragement of free-thinking. As a result, it is not difficult to understand how such accomplishments have been admired over the centuries, and how they played an important role in the development and trajectory of Chinese art.

JW: Tell us about some of the recently excavated objects found in In A Time of Chaos; where were they found, and what is their significance?

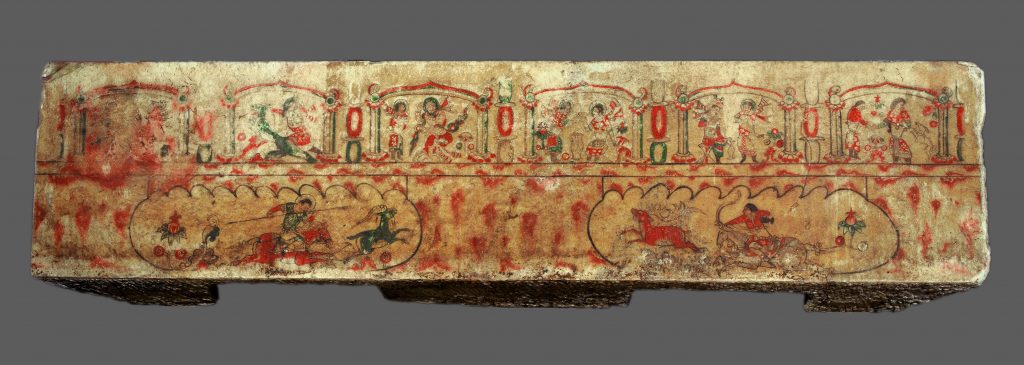

WWH: So many items found within the exhibition were unearthed during the last 15 years. For example, one group of celadon figures was excavated from a royal tomb in 2006. These figures came from the ancient Wu Kingdom. They are the only such set of figures to have been found so far, and they perfectly show the height of artistic brilliance in molding, firing, and glazing. Another interesting fact is that these figures vividly show the cultural tastes of the Wu people: Their clothing, lifestyle and even their expressions. One figure is even attended by a foreign assistant!

Another celadon jar with underglaze painting, unearthed in 2004, is among three or four of the earliest surviving samples with this technique. One dated wooden slip indicates the year was “the first year of the Chiwu era,” the equivalent to the year of 238 CE, so we know that the underglazing technique appeared as early as the third century CE . There is also a marvelous bronze Buddha figurine, which was found in Nanjing in 2007. This artifact dates from 527 CE, and it is quite useful as a standard piece through which one can study Buddhist art from southern China.

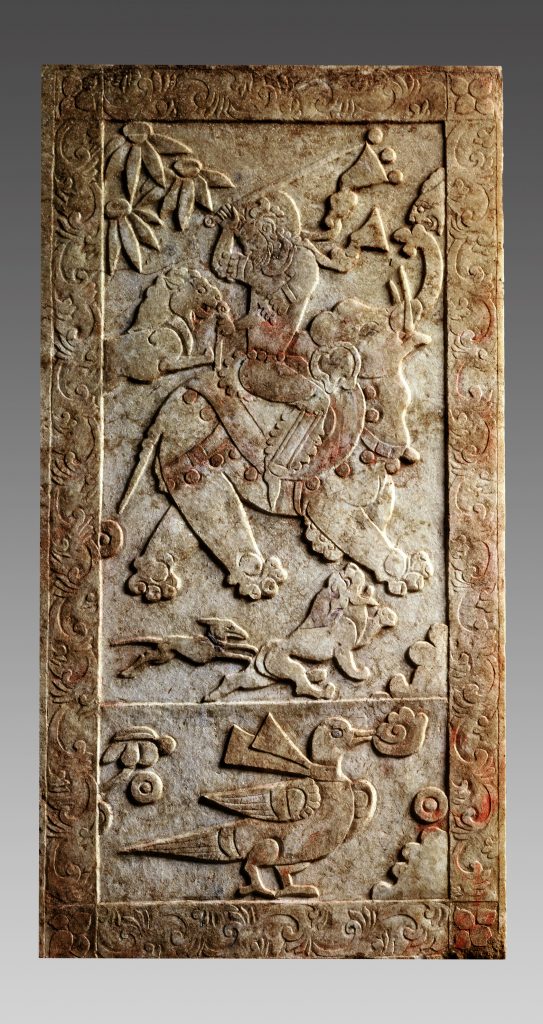

JW: Many of the specimens shown within the exhibition belie strong foreign influences from Central Asia, Iran, and India. Why is this the case, and why was China more open to outside influences at this point in time?

WWH: This is an excellent question, James. During this tumultuous period, there was a high incidence of “political turnover.” Kings and emperors were routinely overthrown or deposed, which caused borders to be poorly guarded. (This was particularly true in northern China.) Many parts of northern China were also ruled by political elites and royal families of foreign origin too. One should not forget as well that foreign merchants, diplomats, and monks actively used the Silk Road to enter China. In southern China, there are records from the third century CE, which state that the Wu Kingdom built huge ships to sail throughout the East and South China Seas in order to conduct business. This period was a much more open era than others in Chinese history, and it can be considered as one of the first active periods of cultural exchanges between the East (China) and the West (India, the Middle East, and Europe).

JW: Could you share with us some more information about the religious climate of the Six Dynasties era, and how it affected artistic production?

WWH: During Six Dynasties period, there was a shift away from the from the dominant Confucian influence of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) to the ancient Daoist philosophers of Laozi (c. 571-471BCE) and Zhuangzi (c. 369-286 BCE), whose concepts like wuwei (follow the nature and do nothing) became much appreciated. This shift helped form the “Qing Tan” (“purity talk” or “intellectual talk”) of the time. New philosophical concepts and the favoring of Daoism can be seen in the aesthetic preference of the color of celadon.

Special note ought to be made of Buddhism too, as it became more influential and powerful in this period. In southern China, the first Buddhist temple was built in the third century CE in the southern capital of Jiankang (present-day Nanjing in Jiangsu province). By the sixth century CE, nearly 500 temples were built, which is a truly stunning achievement. As many of your readers likely know, the Silk Road became a conduit, which transported officials, monks, artisans, and engineers to oversee the construction of the famous caves along the Silk Road. These ran from Dunhuang in the west to Yungang in the east. Buddhist sculpture altered Chinese preferences and aesthetic tastes over time — in matters relating to fashion and self-expression — and Buddhist art became a major category in genre of Chinese sculpture. Buddhism additionally influenced decoration and interior decor; for example, the typical lotus pattern was originally a Buddhist motif from ancient India. It became widely used in decorating celadon vessels or bowls around the early fifth century CE, gaining increased popularity in the sixth century CE.

JW: What are several objects that would be visitors to Art in A Time of Chaos: Masterworks from Six Dynasties China, 3rd-6th Centuries should not miss? Do you have a personal favorite?

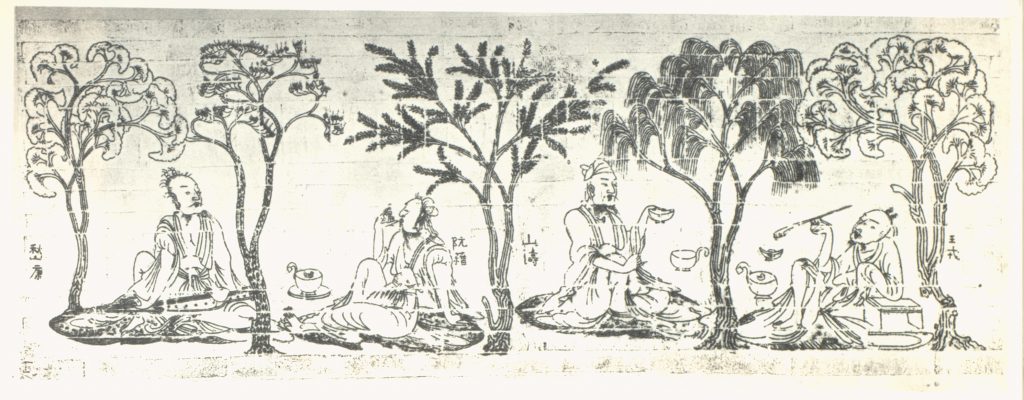

WWH: Oh James, you put me in a difficult position as this exhibition has so many “should not miss” items. Of course, much will dependent on the visitor’s preferences and tastes, but I believe there is something for everyone here. My favorite piece is in the painting section “The Seven Sages of Bamboo Grove.” It is an exquisite work of art.

JW: Thanks so much for speaking with us!

WWH: My pleasure James, thank you and welcome to all your visitors.

Art in a Time of Chaos: Masterworks from Six Dynasties China, 3rd-6th Centuries runs at the the China Institute in New York, New York until March 19, 2017.

Cover Image: Group of Celadon Figurines. Three Kingdoms period, Wu kingdom (222–280 CE). Glazed porcelain; various dimensions, from 5 3/8 to 7 5/8 in. Unearthed in 2006 from the Wu tomb at Shangfang in Jiangning, Jiangsu. Collection of the Nanjing Municipal Museum. (Courtesy of the China Institute.)

Willow Weilan Hai, Director of China Institute Gallery at China Institute in America has been engaged in the field of Chinese art history in the United States for nearly 28 years. She is Chief Curator of the Art in a Time of Chaos exhibition. Her scholarly contributions to numerous exhibitions and catalogues have been acknowledged by art critics and art historians alike. Since 1989, Ms. Hai has contributed to, supervised, and produced more than sixty exhibitions at China Institute Gallery, including a number of recent exhibitions that use newly excavated archaeological artifacts to articulate the great legacy of Chinese art. Since curating her first acclaimed international exhibition in 2003, Passion for the Mountains: Seventeenth Century Landscape Paintings from the Nanjing Museum until the current Art in a Time of Chaos: Masterworks from Six Dynasties China, 3rd–6th Centuries, Ms. Hai has brought a unique Chinese cultural perspective to the exhibitions under her leadership while also making them more accessible to the general public. Born and trained in China, Ms. Hai holds undergraduate and Master’s degrees in History and Archaeology from the prominent Nanjing University, where she is also among the first generation of Chinese archaeologists trained after the Cultural Revolution. She has participated in several excavations. Prior to her arrival in the United States, she served as an assistant professor at the Nanjing Normal University, where she established the first course in Chinese Archaeology and the companion textbook. Over the last two decades, Ms. Hai also has lectured extensively on Chinese art and culture at American museums and universities.

Willow Weilan Hai, Director of China Institute Gallery at China Institute in America has been engaged in the field of Chinese art history in the United States for nearly 28 years. She is Chief Curator of the Art in a Time of Chaos exhibition. Her scholarly contributions to numerous exhibitions and catalogues have been acknowledged by art critics and art historians alike. Since 1989, Ms. Hai has contributed to, supervised, and produced more than sixty exhibitions at China Institute Gallery, including a number of recent exhibitions that use newly excavated archaeological artifacts to articulate the great legacy of Chinese art. Since curating her first acclaimed international exhibition in 2003, Passion for the Mountains: Seventeenth Century Landscape Paintings from the Nanjing Museum until the current Art in a Time of Chaos: Masterworks from Six Dynasties China, 3rd–6th Centuries, Ms. Hai has brought a unique Chinese cultural perspective to the exhibitions under her leadership while also making them more accessible to the general public. Born and trained in China, Ms. Hai holds undergraduate and Master’s degrees in History and Archaeology from the prominent Nanjing University, where she is also among the first generation of Chinese archaeologists trained after the Cultural Revolution. She has participated in several excavations. Prior to her arrival in the United States, she served as an assistant professor at the Nanjing Normal University, where she established the first course in Chinese Archaeology and the companion textbook. Over the last two decades, Ms. Hai also has lectured extensively on Chinese art and culture at American museums and universities.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to AHE by Ms. Willow Weilan Hai and the China Institute have been done so as a courtesy, and we thank her warmly for her generosity. Additional gratitude is extended to Ms. Nicole Straus of Nicole Straus Public Relations and Ms. Margery Newman for helping facilitate this piece. Interview edited by James Blake Wiener for AHE. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2017. Please contact us for rights to republication.