For over a millennium, Byzantine artists in Greece produced sumptuous works of extraordinary quality and caliber. Whether inspired by the ethos of the new Christian religion or the tangible legacy of classical antiquity, these Greek artisans and craftsmen created a uniquely “Byzantine aesthetic,” which in time came to influence the artistic traditions of Italy, Russia, the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Near East.

For over a millennium, Byzantine artists in Greece produced sumptuous works of extraordinary quality and caliber. Whether inspired by the ethos of the new Christian religion or the tangible legacy of classical antiquity, these Greek artisans and craftsmen created a uniquely “Byzantine aesthetic,” which in time came to influence the artistic traditions of Italy, Russia, the Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Near East.

In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia speaks to Dr. Mary Louise Hart, Associate Curator of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum, about Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, on view now at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, CA. This magnificent exhibition explores the breadth, balance, and beauty of Byzantine art from medieval Greece.

JW: Dr. Mary Louise Hart, welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia! This is our first interview to cover the rich and enduring legacy of Byzantium and Byzantine art, and we thank you for sharing your expertise and observations.

Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections is the largest gathering of Byzantine objects ever to be displayed in Los Angeles, CA. Among the treasures — drawn from 34 major collections in Greece — one finds the chief ornaments of Byzantine art: icons, mosaics, manuscripts, jewelry, frescoes, gold coins, and glass.

Of the items presented, which among them are the most unusual and precious? Are there any objects that might surprise or challenge preconceived notions of “Byzantine art”?

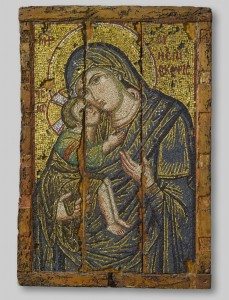

MLH: Many objects in this exhibition are considered masterpieces; all are unique and of the highest accomplishment. The types of art visitors will see — especially the icons and the mosaics — will be expected by those who have some knowledge of Byzantine art. But some may be surprised at the extraordinary quality on view — much of it never before seen outside of Greece — as well as the deeply emotional spiritual power it conveys. Byzantine style has a reputation for being flat and static; this exhibition counters that notion with works of extreme grandeur and emotion conveyed in a variety of media, including fresco, panel-painting, and micro-mosaic.

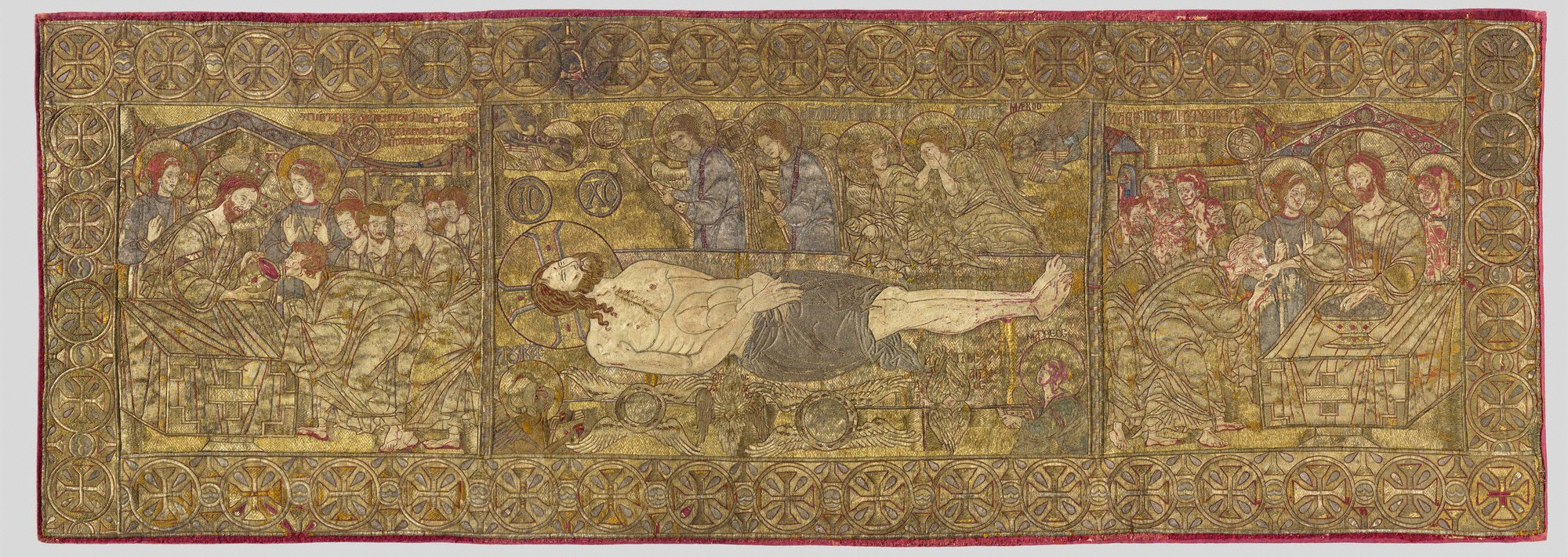

One of the most extraordinary comes in the medium of embroidery: an Epitaphios created in Thessaloniki during the Palaiologos dynasty (1261-1453 CE) to cover the chalice and paten — or “diskos,” a small plate made of silver or gold — that held the bread and wine for Orthodox communion. This seventy-inch long textile sewn in silver and gold-wrapped silk thread depicts Christ laid on his shroud as its central scene, protected by no less than four kinds of angels and surrounded by symbols of the four evangelists. It is the most important surviving example of embroidery from this period.

One of the most extraordinary comes in the medium of embroidery: an Epitaphios created in Thessaloniki during the Palaiologos dynasty (1261-1453 CE) to cover the chalice and paten — or “diskos,” a small plate made of silver or gold — that held the bread and wine for Orthodox communion. This seventy-inch long textile sewn in silver and gold-wrapped silk thread depicts Christ laid on his shroud as its central scene, protected by no less than four kinds of angels and surrounded by symbols of the four evangelists. It is the most important surviving example of embroidery from this period.

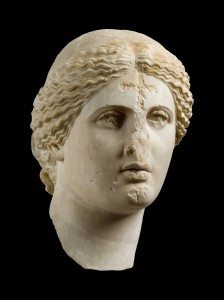

Another work — never before loaned outside of Greece — is the Icon of the Archangel Michael from the Byzantine and Christian Museum in Athens. Painted in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, during the first half of the 14th-century CE, this masterfully executed icon must once have joined others of the Virgin, John the Baptist, and apostles framing the central icon of Christ in the templon screen of an important — yet unspecified — major Orthodox church in the city. Michael’s idealized facial features and classically-styled drapery reveal the pervasive influence of ancient forms on Byzantine style. The inscription, “Christ the Just Judge,” on the orb is a reference to the Second Coming as is Michael’s epithet “Taxiarch” (“military angel” in Greek), inscribed beneath his name in the upper right of the icon.

JW: Heaven and Earth surveys the artistic development of Byzantine civilization from the founding of Constantinople in 330 CE to the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 CE. This was a period of immense artistic and cultural progression. I am curious if you might offer a word as to how the exhibition is organized thematically and how objects are arranged throughout the Getty Villa?

Additionally, how was the Getty Museum able to link and integrate the iconography of classical antiquity to the numerous objects on display?

MLH: This exhibition was organized by the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports in collaboration with the Benaki Museum in Athens, in association with The National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and the J. Paul Getty Museum. The approximately 170 objects were organized into five themes by our Greek associates: From Antiquity to Byzantium, Spiritual Life, Intellectual Life, Pleasures of Life, and Cultural Crosscurrents. The Villa special exhibitions galleries are installed according to these themes and take advantage of the adjacency of the permanent collection of Greek and Roman art.

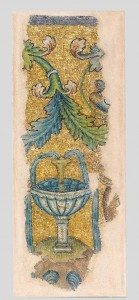

In the first gallery, late antique marbles, including fragments from the Christianized Parthenon and one of the oldest surviving early Christian gold mosaics, are set off against the color of the blue Greek sky. The palette then changes to a jewel-toned red representing Byzantium for the remainder of the installation, which exhibits Orthodox liturgical objects of great rarity and delicacy installed adjacently to icons of extraordinary visual power. The Pleasures of Life and Cultural Crosscurrents are installed in one large gallery with glittering jewels dating from as early as the fourth century CE and the accoutrements of the elite home with ceramic and bronze table wares including the first forks to have been used as personal utensils. This section covers the period of the Crusades, Mystras, and the Post-Byzantine icons of Crete, whose capital, Candia, included the most sophisticated painters in the Mediterranean amongst its wealthy population in 1500 CE.

In the first gallery, late antique marbles, including fragments from the Christianized Parthenon and one of the oldest surviving early Christian gold mosaics, are set off against the color of the blue Greek sky. The palette then changes to a jewel-toned red representing Byzantium for the remainder of the installation, which exhibits Orthodox liturgical objects of great rarity and delicacy installed adjacently to icons of extraordinary visual power. The Pleasures of Life and Cultural Crosscurrents are installed in one large gallery with glittering jewels dating from as early as the fourth century CE and the accoutrements of the elite home with ceramic and bronze table wares including the first forks to have been used as personal utensils. This section covers the period of the Crusades, Mystras, and the Post-Byzantine icons of Crete, whose capital, Candia, included the most sophisticated painters in the Mediterranean amongst its wealthy population in 1500 CE.

JW: It is fascinating to see many secular and everyday objects of remarkable quality presented in the exhibition. Combs, jewels, and lamps, reveal much about the patterns of daily life in the Byzantine Empire.

What could account for the exceptional level of workmanship in Byzantine Greece? It is extraordinary that these pieces were able to survive the test of time.

MLH: You have asked two connected questions: why was it so good, and how has it lasted so long? One could say it endured because it was so good, and that is part of the answer. The other part is that “miracles” allow for the preservation and excavation of extraordinarily rare objects, like the fourth century CE silver reliquary from Thessaloniki or the gold diatrita-work neckpiece from the Goulandris Museum in Athens. Some precious materials were secreted away together with other valuable objects as a hoard, such as happened with the Kratigos Treasure, found on the island of Lesbos quite accidentally when they were excavating to build a new airport.

The best workmanship is attributed to craftsmen-artisans in Constantinople, simply because it was the capital, the court was there, and the means were present to support the best possible work — i.e. wealthy patrons supported continued excellence of workshops and the import of the best and rarest materials.

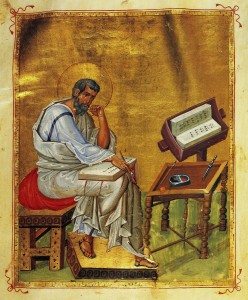

JW: At the Getty Center, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Illumination at the Cultural Crossroads showcases 18 Byzantine manuscripts, six of which come from Greek collections.

JW: At the Getty Center, Heaven and Earth: Byzantine Illumination at the Cultural Crossroads showcases 18 Byzantine manuscripts, six of which come from Greek collections.

Why did the Getty Museum decide to organize this complimentary and comparative exhibition, and why were Byzantine manuscripts chosen as the subject of focus?

MLH: This exhibition, curated by my colleagues, Drs. Elizabeth Morrison and Justine Andrews, was conceived out of the need to give the manuscripts “a room of their own” so to speak — the presentation at the Center gave us an opportunity to install them in a focused presentation with other manuscripts from the Getty collection in order to show the influence of Byzantine manuscript illumination on cultures adjacent to its borders.

JW: Heaven and Earth concludes its survey of Byzantine art with an impressive selection of “Post-Byzantine” icons from the island of Crete, which the Venetians controlled until 1669 CE. From c. 1400-1700 CE, the Cretan School emerged as the leading center of Greek painting in Europe. The artists of the Cretan School blended Byzantine and Western (chiefly Venetian) artistic traditions and styles, creating in turn a distinctive style of icon-painting. The icons produced by the Cretan School were coveted across the Mediterranean, from Mt. Athos to Genoa.

What makes these icons so exceptional in your opinion? Additionally, how important was it to include them in the exhibition?

MLH: Visitors to the exhibition are often surprised to hear that the island of Crete — or “Candia” as it was then called — was the location of the most sophisticated painting atelier in the Mediterranean in the 15th-century CE. After all, the attention of most art lovers is focused on the Italian schools of that time; for example, Florence, Milan, Rome. But Crete? The story of a fascinating culture arises from the history of politics and trade, punctuated by the fall of the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople in 1453 CE, when the best painters in Byzantium were forced to flee to Candia. Others went as far as the Muscovy (Russia), Serbia, Montenegro, and of course, the city-states of Renaissance Italy. Some Greek artists went to the island of Rhodes and established a school there as well.

The island of Candia (present-day Crete) had been a Venetian colony since 1211 CE — after the Fourth Crusade, 1202-1204 CE — and its capital city, also named Candia (modern Heraklion), was considered the second city — after Venice — in the Venetian Empire. By around c. 1400 CE, the island’s central location on maritime trade routes had secured a healthy economy for the island, whose exports included the famous local wine, cheese, and oil. Additionally, goods from all around the Mediterranean — from the Venetian lagoon to the ports of the Black Sea, to Egypt, Cyprus, Syria, and Rhodes — passed through one of Candia’s two ports: Candia itself, located on the northern coast, or Chania in the west. Revenue from shipping boosted the local economy and the increasingly urbane and cosmopolitan ambiance of the island. Latin was the language of government and business, but Greek continued to be spoken by the local inhabitants.

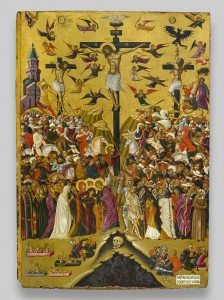

Artistically, Candia’s long history with Venice, coupled with its extensive occupation under Byzantine rule, created an island culture characterized by fealty to both traditions. Traces are evident across many art forms, but in this exhibition icons in particular trace the relationship between Italy [mostly Venice] and the centuries-long visual tradition of Byzantium. Nowhere is the ethnic makeup of Candia better seen than on the Icon of the Crucifixion from the National Gallery of Greece in Athens. Exhibited there as the initial work in that museum’s display of modern Greek painting, this incredibly rich panel is composed of three major registers: above, the crucifixion of Christ surrounded by weeping angels; in the middle, the populace who witnessed the crucifixion; and at the bottom, the underworld with devils and the dead rising from their tombs as soldiers play dice for Christ’s robe. The artist was Andreas Pavias (d. after 1504 CE), first mentioned in 1470 CE as an art teacher, who proudly signed “Painter of Candia” at the bottom right of the painting. The landscape, the treatment of space, and the gilded background all testify to the Byzantine heritage of this painter, yet the tumult of  humanity crowding into the composition and their extraordinarily vivid and detailed portrayal communicates this pivotal Christian event in the most descriptive and intense way possible.

humanity crowding into the composition and their extraordinarily vivid and detailed portrayal communicates this pivotal Christian event in the most descriptive and intense way possible.

In the center field, left, are armed horsemen (with the Three Wise Men) underneath the Temple of Solomon (which has split in two) and the crucifixion of the Good Thief (whose soul is being carried to Heaven by an angel) — on the right are the Ottoman Turks, riding in under the crucifixion of the Bad Thief (with a Devil catching up his soul) and the Hanging of Judas. The narrow field beneath contains a multitude of figures, each with a different cap of rank, and beneath them on the left the sacred group with the fainting Virgin surrounded by the faithful. To the right is Candia’s Jewish community. Everyone witnessing the Crucifixion is clothed in garments made from the most sumptuous and expensive silks and woolens. Separating the Christians and Jews, the figure of a man, turning away, has extended a vinegar-soaked sponge to Christ at the last moment before his death. He holds the vinegar-pot in his left hand.

Once introduced to the detailed narrative of this panel, visitors quickly become aware that the more they seek, the more they will find. The composition draws one in, in hopes of discovering another vignette, another character, and more messages from the world of Andreas Pavias. Presented as the last painting in the exhibition, the Crucifixion brings us full circle from late antiquity to the edge of the modern world.

JW: I thank you so much for introducing us to Heaven and Earth! We look forward to the Getty Museum’s next exhibition with great anticipation.

MLH: Thank you for your interest, James. Working on this exhibition has been an extraordinary experience and I am grateful to my colleagues in Greece and at the National Gallery in Washington for their generous collegiality. I hope that readers might also be interested in two other shows at the Getty Villa: Molten Color: Glassmaking in Antiquity and Relief with Antiochos and Herakles, which runs through May 4, 2015. Other exhibitions of interest include Ancient Luxury and the Roman Silver Treasure from Berthouville (running from November 19, 2014 — August 17, 2015), Dangerous Perfection: Funerary Vases from Southern Italy (on show from November 19, 2014 — May 11, 2015), and Chivalry in the Middle Ages (running from July 8 — November 30, 2014).

Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections will remain on show at the Getty Villa in Los Angeles, CA until August 25, 2014. Over 60 of the objects will travel to the Art Institute of Chicago after their exhibition at the Getty Villa, where they will be on display (under the same title) from September 29, 2014 – February 15, 2015.

Please see Ancient History Encyclopedia’s review of the exquisite Heaven and Earth exhibition catalogue.

Image Credits:

- Epitaphios. Greek, about 1300 CE. Silk and linen. Object: H: 63.5 x W: 179.1 cm (25 x 70 1/2 in.). Image courtesy of the Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki. VEX.2014.2.168.

- Archangel Michael. Greek, first half of 14th century CE. Tempera on wood, gold leaf. Unframed: 110 x 80 cm (43 5/16 x 31 1/2 in.). Image courtesy of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, Gift of a Greek of Istanbul, 1958. VEX.2014.2.57.

- Mosaic wall decoration fragment. Greek, mid-5th century CE. Gold and glass tesserae. Framed: 190.5 x 74.3 x 3.2 cm (75 x 29 1/4 x 1 1/4 in.). Image courtesy of the Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki. VEX.2014.2.171.

- Mosaic icon with Virgin Episkepsis (shelter) and Child. Greek, late 13th century CE. Glass and gold tesserae on wood. Object: H: 107 x W: 73.5 x D: 7 cm, 40 kg (42 1/8 x 28 15/16 x 2 3/4 in., 88.184 lb.). Mosaic: 95 x 62 cm (37 3/8 x 24 7/16 in.). Image courtesy of the Byzantine and Christian Museum, Athens, inv. no 990. VEX.2014.2.52.

- Silver plate with Eros riding a sea-monster. Greek, 6th-7th century CE. Silver. Object: Diam.: 13 cm (5 1/8 in.). Image courtesy of and © Benaki Museum, Athens, 2013, inv. no 11447. VEX.2014.2.20.

- Head of Aphrodite. Greek, 1st century CE. Parian marble. Object: H: 40 cm (15 3/4 in.). Image courtesy of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. VEX.2014.2.85.

- Bracelet. Greek, 9th-10th century CE. Gold with granulated decoration and enamel. Object: H: 7 x W: 8.6 x D: 6.6 cm (2 3/4 x 3 3/8 x 2 5/8 in.). Image courtesy of the Museum of Byzantine Culture, Thessaloniki, inv. no BKO 262/6. VEX.2014.2.167.

- The Four Gospels. Greek, mid-10th century CE. Parchment. Closed: 29.8 x 46.4 x 6.7 cm (11 3/4 x 18 1/4 x 2 5/8 in.). Image courtesy of the National Library of Greece, Athens, cod. 56. VEX.2014.2.71.

- Necklace. Greek, 4th century CE. Gold, precious stones. Object: 12.8 x 22.8 cm (5 1/16 x 9 in.). Plaque: 2.6 x 2.2 cm (1 x 7/8 in.). Mount: 24.1 x 34.3 x 1 cm (9 1/2 x 13 1/2 x 3/8 in.). Image courtesy of the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, no. Z.438.1. VEX.2014.2.88.

- Andreas Pavias. Cretan, died 1512 CE. Crucifixion, about 1440–1504/1512 CE. Greek. Egg tempera on wood. Unframed: 83.5 x 59 x 5.7 cm (32 7/8 x 23 1/4 x 2 1/4 in.). Image courtesy of the National Gallery, Athens, no. 144. VEX.2014.2.69.

Dr. Mary Louise Hart is Associate Curator of Antiquities at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Dr. Hart is the Curator of Heaven and Earth: Art of Byzantium from Greek Collections, in partnership with the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and the Benaki Museum in Athens as well as The Art of Ancient Greek Theater, and author of The Art of Ancient Greek Theater and Understanding Greek Vases. Dr. Hart is a specialist in the art history of myth, epic, and theater. She speaks widely on these topics, most recently at the Oxford Archive for the Performance of Greek and Roman Theater, and at the British Museum as the 2014 Denys Haynes Memorial Lecturer. As the curator behind the founding of the Villa’s theater program, her interests extend to dramatic performance and its reception, including opera. Current art historical research projects include an article in process on “The Iconography of Euripides” and the art of the late antique Mediterranean, especially Romano-Egyptian panel painting and ancient textiles.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Villa, and Dr. Mary Louise Hart have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview and are copyrighted. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Ms. Desiree Zenowich, Senior Communications Specialist at J. Paul Getty Museum for helping arrange this interview. Special thanks is also extended to Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt, who assisted in the editorial process, as well as to Ms. Milena Rodban. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia. All rights reserved. © AHE 2014. Please contact us for rights to republication.