Easter Island or “Rapa Nui” is among the most remote islands in the world, located some 3541 kilometers (2,200 miles) off the coast of Chile in the Pacific Ocean. Famous for its mysterious yet iconic statues (moai), Easter Island is currently the subject of a new exhibition at Manchester Museum in Manchester, UK: Making Monuments on Rapa Nui: The Statues from Easter Island. This show explores the incredible artistic, cultural, and religious traditions of the Rapanui people.

In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener speaks to Mr. Bryan Sitch, Deputy Head of Collections at Manchester Museum, about the engineering and construction of the moai, their purpose in the lives of the islanders, and the intrepid explorers who sought to understand them.

Moai against a setting sun on Easter Island, Chile. Adam Stanford @Aerial-Cam for RNLOC. (Courtesy of Manchester Museum.)

JW: Mr. Bryan Sitch, welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia! This is the first interview we have ever conducted with Manchester Museum, as well as the first to encompass the perennially intriguing topic of the moai statues.

Why has Manchester Museum chosen to create an exhibition encompassing Rapanui and their moai? One cannot deny that there is considerable public interest in these monolithic statues.

BS: Thank you for inviting me, James. Manchester Museum’s temporary exhibition Making Monuments on Rapa Nui: The Statues from Easter Island is the happy convergence of an offer to lend statue from Easter Island, “Moai Hava,” as part of the British Museum’s National Programs, and the fact that Professor Colin Richards of the University of Manchester’s Department of Archaeology has been carrying out excavations on Rapa Nui. Richards is one of the co-investigators on an AHRC (Arts and Humanities Research Council) funded program of fieldwork involving the University College London, University of Manchester, Bournemouth University and Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology (ORCA), University of Highlands and Islands, as well as Rapanui and Chilean archaeologists.

Manchester Museum regularly works with academics across the campus on temporary exhibition projects, the intention being to bring the results of their research to a wider audience here in the museum. In this way the museum is able to draw upon the most recent research in support of its temporary exhibitions, which implement the two principal strands of the organization’s mission: to promote understanding between cultures and to develop a sustainable world. The Making Monuments exhibition is the latest such “academic-led” project with which I, as Curator of Archaeology and Deputy Head of Collections, have been involved.

JW: Making Monuments on Rapa Nui deconstructs many of the prevalent myths about the island and introduces several current theories about the decline of the culture that once flourished there.

What are among the most egregious myths that the exhibition overturns in your opinion? Additionally, among the contemporary theories of decline, which make the most sense in explaining the dramatic population collapse on Rapa Nui?

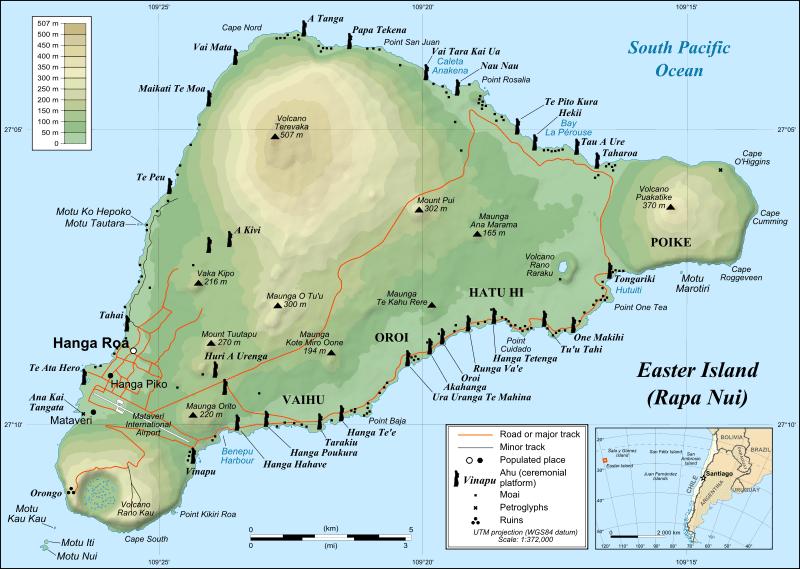

Map of Easter Island, using moai to show locations of various ahu (ceremonial platforms). There are close to 900 moai on the island; presently, half are still in the quarry where they were originally made, but the other half are located around the island’s perimeter. (Original uploader was Eric Gaba at en.wikipedia, 2008-21-10. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license.)

We don’t know precisely how the statues functioned. Early accounts describe the Rapanui kneeling before the statues with their hands raised as in prayer. The moai seem to have been the means by which the power or mana of important ancestors was invoked.

BS: There are lots of myths about Easter Island, and we certainly don’t claim to be the first to challenge them in our Making Monuments exhibition. However, we do say clearly that the idea that people from the Americas settled Pacific islands, like Rapa Nui, is wrong. This was the hypothesis of the Norwegian anthropologist Thor Heyerdahl (1914-2002) who famously drifted across the Pacific on the raft Kon-Tiki in 1947 in order to test his proposition. This was a great public relations stunt, but it was ultimately misleading and did the Polynesians a disservice. The later 1950s expedition led by Heyerdahl looked for evidence of South Americans on Easter Island, although to be fair to Heyerdahl, the archaeologists on the team were free to draw their own conclusions about the evidence. As John Flenley and Paul Bahn make clear in their book Easter Island, Earth Island, a mass of linguistic, ethnographic, ethno-biological, and archaeological evidence shows that the Rapanui were Polynesians, and that their arrival on the island was a continuation of their astonishing voyages throughout the Pacific Ocean. The Rapanui people arrived on the island between the years 300 and 1200 CE, and they began carving moai between 1150-1250 CE. It is likely that they continued to erect moai until about 1500-1600 CE.

Another one of the stories about Easter Island or Rapa Nui is that a disaster overwhelmed the people of the island, leading to the abandonment of statues that were in transit along roads or trackways coming from the quarries. If you follow the “eco-disaster theory,” the supply of wood failed and the Rapa Nui ran out of rollers on which the statues were moved. The work of the British team shows that statues (moai) and topknots (pukao) were erected in these locations intentionally as a way of marking the approaches to the quarries, which were regarded as deeply meaningful, symbolically and spiritually important spaces. A number of toppled moai can be seen leading up to the ahu — a sacred ceremonial place where there are various supports for the moai — as they were another special place in the eyes of the Rapanui.

The question you raise about theories to explain the decline of Rapa Nui’s unique culture is something we skirt in the exhibition because we found there was quite enough to say just about the making of the monuments. However, it is clear from the early accounts that wood was only available in very limited quantities in the early modern period and that something was responsible for the lack of trees. Even if, as looks likely from experimental archaeology, the Rapanui were “walking” their statues to their destinations, they would still have needed wood for levers to raise the statues on their ahu. So the environmental degradation of the island could well have brought an end to the erection of moai. Whether the extensive palm forest that originally blanketed the island was felled entirely by the Rapanui or whether it was unable to regenerate because rats (introduced deliberately or inadvertently by the first settlers) gnawed on the palm nuts and ate the seedlings, is a vexed question. Probably it was both. Other researchers have argued that the Rapanui simply adapted to the new circumstances and that the decline of their culture is really the result of contact with Europeans who introduced diseases, forcibly removed many of the Rapanui for labor in South America, and acquired much of the land.

Entrance to Making Monuments on Rapa Nui at Manchester Museum in Manchester, UK. “Moai Hava” is displayed on the right. Photo: Joe Gardner. (Courtesy of Manchester Museum.)

For my money, the Rapanui’s whole system of beliefs about themselves, the world in which they lived (effectively the island), and the universe was dealt a severe blow by the arrival of Europeans in the 18th century CE. Competition for goods, such as closely woven cloth and previously unknown (to the Rapanui) materials such as iron and brass, created dangerous instability amongst the island’s clans, ultimately leading to bitter fighting. Many of the moai appear to have been toppled in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. Another school of thought proposes that the statues were lowered intentionally over graves, but there is evidence of beheading statues by toppling them onto a stone so that the neck broke. Some argue that this warfare is common in Polynesian societies anyway, and that the fighting was nothing exceptional. However, it seems to me that the large numbers of obsidian weapons or mata’a, and the stories of bitter conflict in Rapanui oral tradition, point to a deeply troubled final phase. Some have argued the mata’a are simply vegetable peelers, but the story of the Rapanui warrior, Tori, who pursued one of the notorious “blackbirders,” shows the mata’a — obsidian-tipped spears — were weapons. Tori was a Rapanui warrior who pursued unsuccessfully a Peruvian Blackbirder or slaver. (Tori met the man years later under more amicable circumstances and told him he could easily have thrown his mata’a and have killed him, but he did not want to throw it at his opponent’s back.)

JW: Mr. Sitch, how were the moai were made and what roles did they play in the lives of the islanders? What ceremonial and spiritual associations did the statues have for those who revered them?

BS: The moai were carved in quarries on the island. Most, but by no means all, were carved from a rock called volcanic tuff at the volcanic crater of Rano Raraku. You might have expected the Rapanui to remove roughly carved blocks of stone, take them to the destination, and then carve them, but they carved the moai complete in the quarry. They created a channel around the outline of the statue in the rock in which to work. The statue remained attached to the bedrock by a narrow keel. The last stage of the process was to chip away at the keel until the statue separated from the rock. It was then slid down the slope of the crater and finished off before being transported (“walked”?) to the final destination. At least, that is, those that were intended to leave, because many stayed in the quarry in various stages of completion.

Moai in the quarry at Rano Raraku, Easter Island, Chile. The moai are still attached to the bedrock by a keel. Photo: Adam Stanford. (Courtesy of Manchester Museum.)

This, what might seem to us to be a rather impractical way of creating the statues, reflected the Rapanui’s cosmology. The discovery by the British team of eyes carved on the quarry face at Puna Pau shows that the Rapanui thought of the rock as animate. In fact, Rapanui genealogies often include entities that were not only not human — neither were they animate. For the Rapanui, the distinctions that we might take to be self-evident did not apply. Removing the keel to separate the statue from the bedrock is rather like cutting the umbilical of a new-born baby, so from a Rapanui perspective, the process wasn’t just an industrial operation, it was the rock giving birth to a statue.

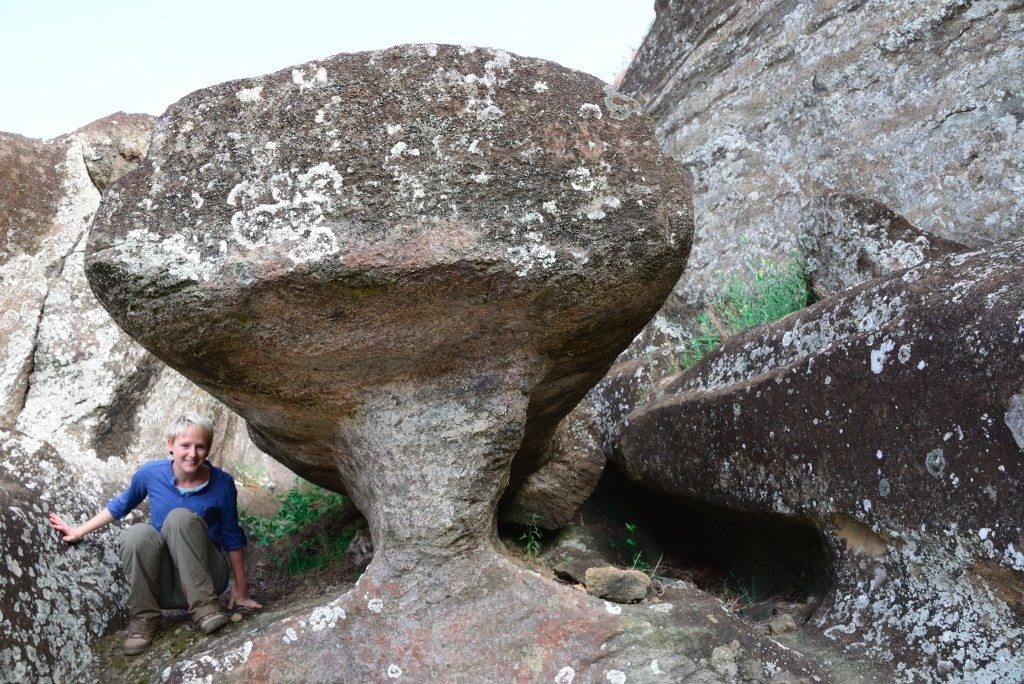

The same technique was applied to removing pukao or topknots from the quarry at Puna Pau. Here the color of the volcanic scoria would have had very important symbolic and spiritual connotations because red represents vitality, power, and authority in Polynesian society. The symbolic importance of the red scoria would have extended by association to the tools that were used to work the rock. Having been in contact with the living rock, they would have been regarded as tapu (the origin of our word “taboo”) and could not be removed from the quarries. So the scatter of stone adzes or toki found there should not be regarded as the result of a sudden catastrophe or a “downing of tools” for whatever reason. The condition of tapu also applied to the workers who would no doubt have prepared themselves for exposure to the rock in the quarries. Volcanic tuff too would certainly have had deep meaning to the Rapanui. Manchester Museum had the privilege of being able to access some truly striking photographs of moai taken by Dr. Paul Horley of CIMAV Campus Monterrey. They show that in certain lighting conditions, the rock has an otherworldly character or luminosity. The Rapanui must have been aware of this and selected the source material for a large number of their moai accordingly.

We don’t know precisely how the statues functioned. Early accounts describe the Rapanui kneeling before the statues with their hands raised as in prayer. The moai seem to have been the means by which the power or mana of important ancestors was invoked. Seeing appears to have played a very important role in their belief system. Eyes made of coral and red scoria were inserted during ceremonies and rituals, apparently to activate the statues. We show a pair of replica eyes in our exhibition.

Moai at Rano Raraku, Easter Island, Chile. Adam Stanford @Aerial-Cam for RNLOC. (Courtesy of Manchester Museum.)

JW: Do we have any idea as to how the moai were quarried and transported across the island? I know that this has been an issue of contention for many decades and is still the subject of fierce scholastic debate.

BS: As the stone can be quite brittle, the statues were almost certainly moved on some kind of sledge, which was moved by means of rollers or even rails. Some researchers have suggested an A-frame was used. One novel explanation is that the statues were walked to their destination. We show some striking artist’s illustrations of moai being walked by teams of Rapanui who tug alternately on ropes in our exhibition. This technique of moving the statues has been demonstrated by experimental archaeology. However, we are not saying this is the only explanation. Clearly, the academic debate is going to run and run.

JW: The exhibition also explores the work of experts who have studied the island in depth. Could you share more information about these pioneers and the roles they played in exploring the island’s unique archaeological heritage?

BS: In our exhibition, we touch upon the work of earlier researchers, such as the English Katherine Routledge (1866-1935), who at no small risk to her own well-being and safety, did so much to interview Rapanui and record information before the opportunity disappeared forever. Katherine and her husband spent time on the island during the First World War (1914-1918) when at one point, German naval forces came ashore. She was also caught up in a Rapanui rebellion against the company that had taken over the island. Routledge preserved for posterity the memories of the unfortunate elderly inmates of the island’s leper colony. Another researcher was the Swiss ethnologist Alfred Métraux (1902-1963) who was part of a Franco-Belgian expedition to the island during the 1930s. Métraux provides invaluable information about the system of beliefs and values of the islanders, and this informs some of the thinking behind Manchester Museum’s exhibition. The lives of both these influential researchers ended tragically, so I am keeping my fingers crossed for me and my colleagues in the exhibition team here!

Seriously though, this project draws on the work of a wide range of academics working in the field of Easter Island studies, too numerous to acknowledge individually here, but I’d like to mention especially members of the British team, especially Richards who has been our “academic lead,” who carried out the recent excavations at Puna Pau, which are a chief feature in our exhibition.

Main exhibition gallery showing replica pukao and model of the Puna Pau “hat” quarry. Photo: Joe Gardner. (Courtesy of Manchester Museum.)

JW: As we conclude, I think it’s worth noting once more that one of the highlights of Making Monuments on Rapa Nui is “Moai Hava,” which was collected in 1868.

Nevertheless, I am eager to learn about the other curiosities awaiting visitors. Could you share a few of them or describe a personal favorite?

BS: Moai Hava, understandably, is the centerpiece of our exhibition. It weighs 3.3 metric tons (7,275 pounds) and stands 1.56 meters tall (5.12 feet), but the the average moai weighs 12.5 metric tons (27,558 pounds) and stands at four meters (13 feet). This statue does not have a pukao, and, it seems, was never intended to have eyes; also, it is made out of basalt rather than volcanic tuff. For these reasons, we show two large replica moai complete with pukao and one of them with eyes in the exhibition. Chris Dean of Freeform Studios Ltd and Peter Spinks of Creative Models have made these. They have done an absolutely first-rate job. They have also made a 3D representation of part of the quarry at Puna Pau, again with eyes, and, in addition, a pukao, complete with a petroglyph.

However impressive these replicas are, visitors naturally want to see real objects from Rapa Nui. Thanks to loans from the British Museum, Horniman Museum and Gardens, Liverpool Museums, the Pitt Rivers Museum, the London Natural History Museum, and Natural History Museum Oxford we can show toki or adzes for carving stone, obsidian mata’a or weapons, wooden dance paddles, a staff or scepter with inlaid eyes of bone and obsidian, a wooden spear with obsidian tip, wooden figures, samples of different kinds of volcanic rock from the island and, my personal favorite, a stone fish hook complete with vegetable fiber trace. Some of these exhibits are the private mementos of colleagues and members of the public.

Linie of Pukao at Puna Pau, Easter Island, Chile. Adam Stanford @Aerial-Cam for RNLOC. (Courtesy of Manchester Museum.)

We also explore the role of Easter Island statues in popular culture and show a selection of comics, First Day Cover stamps, moai mugs and even an EP cover showing statues or moai by Krispy 3. This Manchester based band comes from Chorley and has been very active on the UK and Manchester hip-hop scenes. Now I never thought I’d end up saying that in an exhibition about Easter Island!

JW: Mr. Sitch, I thank you so much for speaking with me on behalf of Ancient History Encyclopedia. Rapa Nui is shrouded in mystery and lore, and it was a treat to discuss this show. We eagerly await Manchester Museum’s next exhibition pertaining to the ancient world.

BS: You might not have to wait that long if our plans for a temporary exhibition about Neanderthals come to fruition. But it’s been a great pleasure to be able to bring the fascinating subject of Easter Island or Rapa Nui to a wider audience.

Whether lent by institutions or individuals, Manchester Museum is very grateful to all those who lent their support. The Bradshaw Foundation kindly provided images of rock art on Rapa Nui. Notable among them were access to detailed drawings of petroglyphs by Dr Georgia Lee (Easter Island Foundation). The Sebastian Englert Museum, Gallery Oldham, The Dorman and Captain Cook Birthplace Museums, the Royal Geographical Society, and the University of Manchester collection provided additional images and exhibits. I might also express the Museum’s gratitude to the funding bodies The Headley Trust and The Dorset Foundation. Exhibition and graphic design was undertaken by FDA Design Ltd.

Ahu Tongariki, Easter Island, Chile. Adam Stanford @Aerial-Cam for RNLOC. (Courtesy of Manchester Museum.)

Making Monuments on Rapa Nui: The Statues from Easter Island will run until September 6, 2015 at Manchester Museum in Manchester, UK.

Mr. Bryan Sitch is Deputy Head of Collections at Manchester Museum, which is part of The University of Manchester in the UK. Previously, he worked in local authority museums in Hull and Leeds before coming to Manchester. The Lindow Man a Bog Body Mystery show (2008-2009) was his first major temporary exhibition project at Manchester Museum. Although a originally a Romanist, Sitch has worked with a wide range of collections, including prehistoric and material of later date, and was responsible for the Scheduled Ancient Monument of Kirkstall Abbey in Leeds, England. He has wide-ranging interests and has also worked with West African material.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Manchester Museum have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Mr. Tim Manley, Head of Marketing and Communications at Manchester Museum, for helping facilitate this interview. Additional thanks is extended to Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt for editorial assistance. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.