Vessel in the form of a Hindu kinnari. Surigao Treasure, Surigao del Sur province. Ca. 10th–13th century. Gold. H. 4 ¾ x W. 2 15/16 in. (12 x 7.5 cm). Ayala Museum, 81.5189. Photography by Neal Oshima; Image courtesy of Ayala Museum. An object uncovered by Edilberto Morales in 1981.

The kingdoms of the ancient Philippines were populated by advanced societies with superior metallurgical technology long before the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan and Spanish explorers in 1521 CE. This fall, New York City’s Asia Society Museum presents an exhibition of spectacular works of gold — including exquisite regalia, jewelry, functional and ritualistic objects, ceremonial weapons, and funerary masks — from collections in the Philippines and United States: Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms. In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia speaks to Dr. Adriana Proser, Senior Curator at Asian Society Museum, about the ways in which this exhibition underscores the place and importance of ancient Philippine craftsmanship and metallurgy.

JW: Dr. Adriana Proser, thank you for speaking to Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) about Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms.

This exhibition is organized into four sections, beginning with an overview of archaeology in the Philippines. The vast majority of the 120 artifacts in Philippine Gold, unearthed between the 1960s and 1980s, affirm the sophisticated metalworking traditions that existed across the ancient Philippines. In 1981, a hoard of gold objects was accidentally discovered in the village of Magroyong in the southern Philippines by the late archaeologist-collector Cecilia Y. Locsin and her late husband Leandro V. Locsin (1928-1994).

Could you characterize the immense of importance of their discovery, and explain why you included a section devoted to archaeological research in an exhibition on Philippine gold?

Burial No. 1, Northeast Mindanao Salvage Project, April 4-6, 1981. Archaeologist Warren Peterson and his team excavated six graves in the site called Masago near present-day Butuan City in 1981. Near the burial, Chinese ceramic shards of the Northern Song period from kilns in Fujian or Zhejiang suggest that the grave dates to the tenth to twelfth century. Image courtesy of the Locsin Collection.

AP: The accidental discovery of a hoard of gold objects in Magroyong by Edilberto Morales, who was driving a motorized scraper for a government irrigation project at the time, ultimately had an enormous impact on our understanding of the power and sophistication of the Kingdom of Butuan between the tenth and eleventh centuries CE. Fortunately these finds came to the attention of Cecilia Y. and Leandro V. Locsin and they made a concerted effort to collect and preserve the objects that were being looted from Magroyong. These objects are of a scale and sophistication not seen previously. They include a variety of forms created using a wide range of gold working techniques. The works are unique, but also show interactions, either direct or indirect, with other regions like present-day Indonesia, China, and India.

However, since this discovery was an irregular find, we felt it was critical to include a section in the exhibition that also gave information about scientifically organized archaeological projects in the Philippines, which help us to understand that the irregular finds are not a complete anomaly. There are documented finds that help us to date and verify the existence of this amazing goldworking culture during this period.

The objects are so spectacular and unique that adults and children alike will be impressed by them. Those who know nothing about the ancient Philippines and its history will be able to appreciate the gold works on the most basic level. Those of us who already know something about Asian art and culture will also see something entirely new. The objects really expand our understanding of early maritime trade and cultural exchange.”

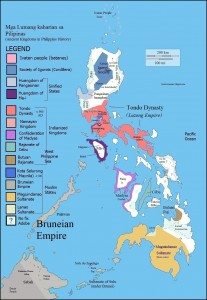

Before the Western contact, the Philippine archipelago had its own kingdoms, which were influenced by China, India, and various Malay kingdoms. (Image created on 5 October 2015 by Philipandrew2. CC BY-SA 4.0.)

JW: The ancient Philippines laid at the intersection of trade between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Monsoons brought traders, sailors, and missionaries to the Philippine archipelago for hundreds of years prior the arrival of the Spanish, so it is no surprise that many of the pieces on display share stylistic, iconographic, and technical similarities with distant and neighboring cultures.

Which of the ancient Philippines’ neighbors exerted the strongest artistic and technical influence in your estimation? Although early Chinese historical sources from the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) attest to a variety of trade missions to what is now the Philippines, one notices a definite influence from ancient India and the Indianized kingdoms of Southeast Asia on many of objects found in Philippine Gold.

AP: It is fair to say that based on what has been found so far, we can conclude that India and Indianized kingdoms of Southeast Asia had the most influence on Philippine gold dating between the tenth and thirteenth centuries CE. As you mention, we know that the Philippine polities were heavily involved with trade. We also know that there were Tamil settlements in the ancient Philippines. What is difficult to determine is exactly how and when these influences began. Most likely they were coming from a number of different places over a long period of time.

Bowl. Surigao Treasure, Surigao del Sur province. Ca. 10th–13th century. Gold. H. 3 5/8 x Diam. 6 11/16 in. (9.2 x 17 cm). Ayala Museum, 81.5179. Photography by Neal Oshima; Image courtesy of Ayala Museum. An object uncovered by Berto Morales in 1981.

JW: Until preparing for our interview, I had never heard of the Kingdom of Butuan. Located on the southern island of Mindanao, Butaun rose to commercial prominence in the tenth century CE and declined in the thirteenth century CE.

What can you tell us about the enigmatic Kingdom of Butuan, and the ways in which its people crafted and utilized gold? Splendid adornments and ritual objects have been recovered from this once wealthy polity, and I believe they can tell us a great deal about social hierarchies and the projection of power.

AP: So much about the Kingdom of Butuan remains a mystery, James. Without written documents and because the inhabitants of this kingdom did not have a stone or brick architectural tradition, we are left to glean what we can from the gold itself, related archaeological finds, and the geography of the place.

What we can tell from what has come to light so far is that the inhabitants of Butuan used gold for imperial regalia, as adornment, and also to fashion religious images. Chieftains had access to the most gold and wore regalia that included gold diadems, heavy necklaces, waist bands, sashes, ear ornaments, and bracelets. In addition, gold was incorporated into funerary practice in the form of gold masks and orifice covers. We assume the full-face masks were made for those with the most power and wealth.

Ear ornament. Eastern Visayas or Northeastern Mindanao, ca. 10th–13th century. Gold. Diam. 1 5/8 in. (4.2 cm). Ayala Museum Collection, Cat. No. 73.4192

Craftspeople used a variety of goldworking techniques and exploited and combined them in very sophisticated and skilled ways. They hammered gold into sheets or foil, crafted objects in repoussé, and incised patterns in the surfaces. They molded gold, wove with gold wire, and created loop-in loop chains of all manners. I think for me the most awe-inspiring of their practices is their use of granulation, especially on gear beads. Each gear bead is a disc entirely built up of granulation and when strung together the beads lock perfectly into one another to create snaking chains. What these techniques and the imagery used tell us is that craftspeople drew some of their inspiration from imagery and techniques from neighboring regions, which maritime trade facilitated. Butuan itself had large wooden boats that could travel great distances for trade and, of course, other countries also sent their trade boats to Butuan. Therefore the people of Butuan were exposed to other cultures in various ways.

JW: It should be noted that the Philippines has the second largest gold deposit in the world, and you certainly can get a sense this when visiting Philippine Gold!

Dr. Proser, why do we know so little about the ancient Philippines and the impressive craftsmanship of the ancient Filipinos? Is it because so much gold was subsequently melted down over the centuries and because there is a dearth of historical records?

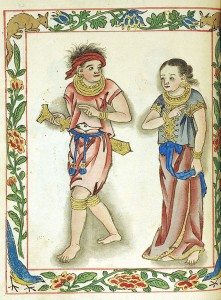

Detail from the Boxer Codex. Collection of the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana. Image courtesy of the Lilly Library.

AP: Exactly, James. A major factor is the dearth of historical records. The only written document from the period that has been found so far is called the Laguna Copper Plate. It is a legal document that records the case of a man who was enslaved due to a debt in gold, but then was acquitted of this debt. Much of the historical record has been destroyed due to the protracted period of colonialism in the Philippines, first under the Spanish and later under the United States, followed by governments that have for one reason or another not put enough resources into funding archaeological projects and protecting areas of archaeological importance.

We know from Spanish colonial historical records that gold was systematically taken from local inhabitants and from burial sites for the Spanish crown. The Spanish had these objects melted down and transformed into bullion and refashioned to create objects for the Catholic Church. The colonial Philippines were an important part of the Manila galleon trade, which crossed the Pacific Ocean from Manila to Acapulco, Mexico. Since that time, a cycle of poverty and desire has fueled the activities of “pot hunters,” dealers, and private collectors. Many people who hunt for gold are simply looking for a way to bring their families out of poverty. In an unsophisticated way, they understand the monetary value of gold, but they often have little or no understanding of the greater historical value of what they find. Sadly, even to this day, objects end up being divided and shared among those who make the finds and sold to dealers who melt the objects down and sell the gold for its value alone.

Set of two barter rings. Surigao Treasure, Surigao del Sur province. Ca. 10th–13th century. Gold. Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, G4P-1982-0001, G4P-1982-0002. Photography by Wig Tysmans, image courtesy of the lender.

JW: The majority of works in the exhibition are on loan from the Ayala Museum and the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Gold Collection (Central Bank of the Philippines); not surprisingly, most of the artifacts exhibited have never been seen outside of the Philippines.

Why should New Yorkers and visitors to the city see this show? Moreover, what differentiates Philippine Gold from other exhibitions the Asia Society has organized in the past?

AP: I really encourage visitors of all kinds to take advantage of seeing these objects while they are in New York. These kinds of objects cannot be seen in collections in the United States and it is highly unlikely the lenders in the Philippines will allow the works to travel to the United States again in most of our lifetimes. The objects are so spectacular and unique that adults and children alike will be impressed by them. Those who know nothing about the Philippines and its history will be able to appreciate the gold works on the most basic level. Those of us who already know something about Asian art and culture will also see something entirely new. The objects really expand our understanding of early maritime trade and cultural exchange. If you look at these objects in a catalogue or on our website, you will get a sense of what they are like, but pictures simply cannot capture how extraordinary these objects are. To understand this, you must see them in person.

Set of two waist cord weights. Surigao Treasure, Surigao del Sur province, ca. 10th–13th century. Gold. Each: H. 2 3/8 in. (6 cm). Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, G7P-1981-0003. Photography by Wig Tysmans; Image courtesy of Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (Central Bank of the Philippines).

This exhibition is different from other shows that we have done because there is still so much mystery surrounding the material on view. I thought hard about that prior to deciding to move ahead with this exhibition. My job as a senior curator at Asia Society is to use art as a means for educating our visitors about Asia and the objects on view. In the end, I decided we had to do this exhibition because even though we know so little, these spectacular objects hint about so much. They are a connection to the past for Filipinos and Filipino-Americans. They are something all humanity can be proud of and inspired by. I want this show to encourage more research and I hope it helps send out the message that we need to preserve areas that, through scientific study, can reveal more about the cultures that produced these gold works.

JW: Dr. Adriana Proser, thank you so much for speaking with me about this lovely show. I hope we shall work with one another again in the near future.

AP: It has been my pleasure, James! I look forward to discussing other Asia Society Museum exhibitions with you in the future.

Philippine Gold: Treasures of Forgotten Kingdoms will remain on display at Asia Society Museum in New York, NY through January 3, 2016.

Dr. Adriana Proser is John H. Foster Curator of Traditional Asian Art at Asian Society Museum in New York, NY. A specialist in Chinese art, over the last fifteen years she has organized and co-organized over forty exhibitions featuring diverse works from all over Asia. These include the loan exhibition Buddhist Art of Myanmar, and the exhibitions Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China’s Liao Empire and Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707-1857 for Asia Society Museum. Her publications include Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art (Asia Society Museum and Yale University Press, 2010), for which she served as editor and contributor. She is recipient of a Ph.D. in Chinese art and archaeology from Columbia University. Proser was formerly Assistant Curator of East Asian Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Adriana Proser is John H. Foster Curator of Traditional Asian Art at Asian Society Museum in New York, NY. A specialist in Chinese art, over the last fifteen years she has organized and co-organized over forty exhibitions featuring diverse works from all over Asia. These include the loan exhibition Buddhist Art of Myanmar, and the exhibitions Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China’s Liao Empire and Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707-1857 for Asia Society Museum. Her publications include Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art (Asia Society Museum and Yale University Press, 2010), for which she served as editor and contributor. She is recipient of a Ph.D. in Chinese art and archaeology from Columbia University. Proser was formerly Assistant Curator of East Asian Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in Philadelphia, PA.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Asia Society have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Special thanks is given to Mr. Juan Machado, Senior Media Officer at Asia Society, for his role in helping make this interview possible. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.