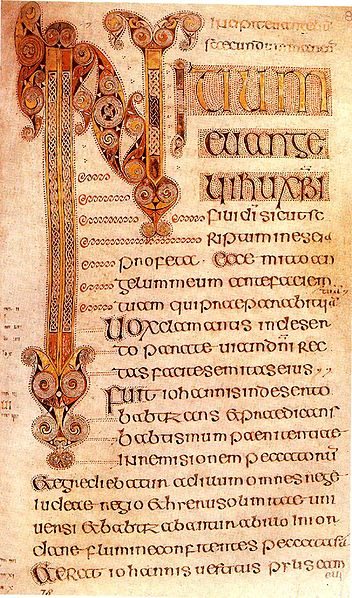

The Book of Kells completed in Ireland, c. 800 CE. This folio shows the lavishly decorated text that opens the Gospel of John.

While much of Europe was consumed by social disarray in the centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, a remarkable golden age of scholasticism and artistic achievement began in Ireland. Untouched by centuries of Roman rule, Ireland retained an ancient cohesive society characterized by rural monastic settlements rather than urban centers. From c. 400-1000 CE — an era more popularly known as the “Age of Saints and Scholars” — Irish missionaries spread Christianity, bringing monastery schools to Scotland, England, France, the Netherlands, and Germany. In doing so, they also transmitted a new, effervescent style of art throughout western Europe: Insular art.

In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Dr. Dorothy Hoogland Verkerk, Associate Professor of Art History at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, about the astonishing history of Insular art.

JW: Dr. Verkerk, welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia, and thank you for speaking to me about Insular art as we approach Samhain.

I wanted to begin by asking you about the roots of Insular art in Ireland: Which factors led to its development and unique compositional elements? Is it fair to say that Insular art was tied to the spread of Christianity, as well as systems of patronization between secular elites and artisans?

DV: What we call Insular art in Ireland has its roots in La Tène culture, the name given to Celtic Continental Europe (c. 450–c. 50 BCE). The remarkable 19th-century discovery of over 3,000 artifacts at La Tène (in Neuchâtel, Switzerland) gave its name to a European culture of the later Iron Age; it was a dramatic find that established the Celts as creators of an artistic tradition that rivaled the Greeks and Romans. The pre-Christian art of Britain and Ireland is hard to pinpoint its beginnings, but scholars generally extend Insular La Tène art up to c. 650 CE.

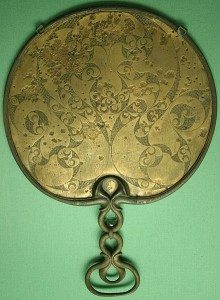

The reverse side of a Romano-Celtic bronze mirror from Desborough, Northamptonshire, England, showing the development of the Early Celtic La Tène style in what is present-day Great Britain. This items dates c. 50 BCE-50 CE.

Insular La Tène art is characterized by curvilinear forms, abstraction, and a high degree of technical expertise in metalworking. It distinguishes itself from Greco-Roman art in that it is determinedly non-narrative despite a great tradition of storytelling. Unlike Greek or Roman art, it rarely shows sexual activity or even the full-length human figure. Shape-changing ambiguity is one of its prime characteristics, with reversible images in which creatures are part-human, part-bird, part-animal and part-mythological monster, where faces peer from foliage out of which they grow, and where foreground and background appear to interchange. It is an art that demands the active participation of the viewer’s imagination; in other words, it is the art of quiet contemplation or you will miss much of the subtleties. From the first century BCE onwards, the art is based on carefully laid-out compass design, and until the coming of the Romans to Britain, most designs avoid straight lines and rectangular spaces.

It is with the introduction of Christianity that there is a marked change in Insular art. One of the main reasons for this is the conversion to a religion based on a sacred text, the Bible. The idea of a book with illuminations is foreign to pre-Christian art in Ireland, Scotland and England. Once the codex, or book, is introduced, a remarkable new type of approach to book illustration is developed. One way to look at it is to think of the book as if it were a person that needs ornamentation to declare status; for example, the Big Man needs a torque and an elaborate sword sheath to announce his wealth and power. Insular artists transfer this idea to the pages of a book. If it is a Gospel Book, which tells of the life and miracles of Jesus Christ, it is particularly worthy of ornamentation. The story of the Incarnation, when the Divine takes on human flesh, will often receive the most elaborate decoration due to its importance in the history of salvation.

Decorated text from the Book of Durrow produced in Ireland or England (Northumbria), c. 650-700 CE. This folio shows beginning of the Gospel of Mark.

Often the ornamentation is so elaborate, it will obscure the clarity of the letters themselves, something a book illustrator trained in the Greco-Roman tradition would never do. Another contribution is to introduce each Gospel book with a decorative page, which is often referred to as a carpet page. This may have two functions: one, to easily find the beginnings of books; and second, it has been suggested that the cross motif and ornamental designs protect the Word from corruption through the use of symbol and magical power. This is hard to prove, but it would be consistent with what is known about medieval beliefs in magic. The result of approaching the illumination of the book as if it were jewelry or metalwork was to fundamentally change the relationship between word and image.

I am not an expert on patronage and artisan systems, but it would be fair to say that kings in Ireland were accustomed to patronizing the arts. And in Ireland, the abbot of a monastery was often from a royal family.

JW: The Book of Kells (c. 800 CE) is the first experience many have with Insular art, and one cannot help but be awed by its dazzling intricacy and refinement.

Dr. Verkerk, how were illuminated manuscripts like the The Book of Kells or The Book of Durrow (c. 650 CE) created? If I am not mistaken, art historians still disagree as to the types of tools used in their formation, aside from rudimentary compasses and rulers.

DV: First, it is important to distinguish between illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow. Although both manuscripts are Gospel books, the Book of Kells is a larger format codex that was probably used for display. The Book of Durrow is a small codex, or “pocket gospel,” that was probably used for missionary or teaching purposes. A gospel such as the Durrow example (245 mm x 145 mm) would be carried in a small pouch.

The process of creating an illuminated manuscript would be a long one by our standards and probably involved a number of specialists. First, the vellum would have to be prepared by cleaning, drying, and stretching the skin of the animal. Then it would have to be cut to the appropriate size. The gatherings could be done before the text and illuminations were finished, or it could be done after. This would depend on the number of scribes and illustrators. Typically, the text would be written first, and then a more experienced scribe would correct the text before the ornamentation would be inserted. It is often difficult to determine how many “hands” contributed to the creation of a manuscript since individual “expression” was not a desirable quality. The book would then have to be stitched together and bound. It is conceivable that one person could do all this work, but in a monastic setting, it is more likely that several people were involved.

JW: Some of Europe’s finest decorated manuscripts and artifacts of gold, silver and metal come from early medieval Ireland. However, Irish craftsmen also produced impressive stone crosses or “High Crosses.”

The Picts of Scotland were expert craftsmen of stone too, so is it likely that the Irish derived some inspiration from their Pictish neighbors across the Irish Sea? How does Irish stonework differ from earlier models found throughout the British Isles, and could you comment upon the major innovations in sculpture that occurred during this era?

DV: The Pictish stones remain some of the most enigmatic sculptures in western Europe, particularly the most ancient ones that predate the conversion of the Scots to Christianity. There was a great deal of exchange between the Irish and the people of Scotland; indeed, the term “Scotti” referred to the Irish before the year 1200 CE. The animal symbols found in manuscripts like the Book of Durrow or the Echternach Gospels are remarkably similar to those found on Pictish stones.

I believe the major innovation in early Insular sculpture was the move from wood carving to stone carving. It is believed that the earliest crosses were carved in wood since there is documentary evidence for this practice. Exactly when and why Irish sculptors moved to stone is hard to determine. The craft of carving wood, of course, is very different from chiseling stone. I believe this is an important question that remains to be answered: Why the transition from wood to stone?

For many decades, scholars have been trying to determine the models for the High Crosses: everything from Carolingian ivories or stuccoes to Irish metalwork. There are several problems with these theories: no Carolingian ivories have been found in Ireland, and stucco would not have traveled well. Also, the re-dating of the Ahenny crosses, which are non-figurative, to the second half of the ninth century CE, has put a dent in the theory that first came metalwork, then the purely ornamental crosses, and finally the figural crosses, more commonly known as the “scripture crosses.” Irish sculptors were not necessarily dependent on passive imitation of contemporary models from abroad; they succeeded in formulating their own unique response to Christian thought and ideas, drawing on imagery long familiar within the Irish Church.

The Kilree Cross, located in County Kilkenny, Ireland. This high cross dates from the ninth century CE.

It is important to remember that these were sculptures in the round meant to be lived with in a monastic compound; thus, they were designed and situated to change gradually in appearance and visual emphasis with each rising and setting of the sun throughout the year. Comparisons to Pictish sculptures, Carolingian ivories, metalwork, and manuscripts can be rewarding; however, the large-scale sculptures were experienced in a very different manner. Due to the weathering of the crosses, the precise identification of the figural scenes is hard to determine. That is why I think it is an exciting new avenue of investigation to explore how the crosses may have functioned in Irish society and the monasteries in particular.

JW: It is important to acknowledge that Ireland was not isolated from the rest of Europe despite the fact that the Romans never occupied it. There were many exchanges between the Irish and their neighbors in the British Isles and continental Europe. Additionally, from the ninth century CE onward, there was contact, often bloody, with Norse invaders and settlers.

In your opinion, is the term “insular” thus appropriate to describe this style of art? I have seen some scholars utilize “Hiberno-Saxon” as an alternative. What are your opinions, Dr. Verkerk? Certain nuances — like the interlacing band style — are actually Anglo-Saxon in origin.

DV: In discussions of the early medieval cultures of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England, rather than identifying terms such as “Britain,” “Ireland,” “Celtic” or “Hiberno-Saxon,” with their associations of modern national boundaries or elusive ethnic categories, “Insular” recognizes a shared style and avoids unnecessary or illogical national attributions. The term had been promoted in 1901 by the German paleographer, Ludwig Traube (1861-1907), and then adopted by the art historians, Carl Nordenfalk (1907-1992), Nils Åberg (1888-1907) and Meyer Shapiro (1904-1996). In 1985, the Royal Irish Academy, at a conference held at the University of Cork, marked the official embrace of the term “Insular.”

While it is true that “interlace” is Anglo-Saxon, since the first surviving example of it is the Great Buckle from the Sutton Hoo burial, these types of distinctions are modern ones. Imagine, if you will, that an Irish artist sees something like the Great Buckle and says, “That’s gorgeous! I think I’d like to incorporate that idea into my next work.” And from there it takes off. There is a constant back and forth exchange of ornament, pattern and design in all medieval art. So it is less important to trace the origin of a design — who did it first — than it is to appreciate the borrowings and choices made by artists and patrons. I often ask “What was not chosen?”

JW: Dr. Verkerk, what was it that first attracted you to Insular art, and why do you think so many others are drawn to the artwork of this period?

DV: I was first introduced to Insular Art in graduate school since my undergraduate institution, like most in the United States, did not include the study of Insular art in any substantial way. I believe that Insular art appeals to so many because it lacks a narrative; by that I mean that you don’t need a text such as the Bible to appreciate it. Also, the sheer technical mastery, so evident in the manuscripts and the sculpture, is breathtaking. The absence of narrative and the pleasure of the ornament to the eye allow viewers to read into the designs their own interpretations. I also think that the curvilinear aesthetic that finds it origins in vegetation lends itself to contemporary concerns about the environment; for example the Pagan World Tree often incorporates “Celtic” strapwork into its designs. The ornament also appeals due to its mathematical precision that has drawn scholars outside the fields of art history and archaeology to study the geometry of the designs. Insular art is closely allied to the notion of the “Celt.”

All things Celtic have been highly romanticized and the artwork associated with Celtic cultures embraced as part of this “free spirited” idea. The belief of the Celts as fiercely independent, formidable warriors, prone to hard drinking, socializing and storytelling is a deeply ingrained and highly attractive picture that has been embraced by people all over the world. Ironically, the artwork is precise and mathematically structured; yet, this very exactness produces an ornamental vocabulary that is difficult to define.

JW: Although Insular art remained the dominant aesthetic in Ireland until about the 12th century CE — merging with Romanesque styles thereafter — one sees its continuing importance in the Carolingian and Ottonian manuscripts of the Middle Ages.

As we conclude our interview, I am curious to know what is the legacy of Insular art in European art history? It is the departure from a classical or “Mediterranean” approach to ornamentation?

Muiredach’s Cross, located in Monasterboice, County Louth, Ireland. This high cross dates from the tenth century CE.

DV: The greatest contribution, in my opinion, is the new approach to manuscript illumination that merges text and image and ornament. Ornament is too often the poor cousin that frames or decorates a narrative scene but rarely plays a central role for art historians trained in western European art: the Greco-Roman tradition. For the most part, the study of interlace and filigree have been focused on finding commonalities of motifs and rarely on what it meant to decorate not only the work of art, but also the manuscript, the sculpture and even the person. Ornament in other media presents an even greater challenge.

When a work of sculpture on the size and prominence of a high cross — such as Muiredach’s High Cross — dedicates almost half of its carving to abstract ornament, or even when a less ambitious project — such as the Kilree Cross — dedicates all its carving to ornament, this begs the question of why ornament was so important to the patron(s) and sculptors? Also, if there is a relationship between metalwork and sculpture, what is the nature of that relationship? Is it simply the transferal of motifs from portable objects in precious metals to large-scale stone sculpture, or is there something more profound at work?

This, it seems to me, would be a productive area for looking broadly at other cultures, where ornament also takes a prominent role in a variety of media. Here, I am thinking of Islamic art or even Japanese art, where there may be a commonality that could generate fruitful discussions across geographies that are mutually beneficial. A leitmotif throughout the last few decades of medieval Irish art history is the desire to link medieval Ireland to the British Isles and continental Europe. The study of ornament has the potential to link Ireland, at least conceptually, to a larger world by asking: Why ornament?

JW: Dr. Verkerk, I thank you so much for sharing your knowledge and expertise with Ancient History Encyclopedia. I wish you many happy adventures in research!

DV: Thanks so much, James!

Image Credits

- Book of Kells, Folio 292r, Incipit to John: “In principio erat verbum.” Illumination on parchment. Ireland, c. 800 CE. This item is currently held at Trinity College Library, Dublin. Original uploader was Dsmdgold at en.wikipedia, 2005-19-01. (This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art.)

- Decorated Romano-Celtic bronze mirror. Desborough, Northamptonshire, England, c. 50 BCE-50 AD. 36 cm diameter. Symmetrical clover-leaf pattern possibly laid out using a compass or string, engraved with a basket-weave pattern and hatched texturing. Original uploader was Fuzzypeg at en.wikipedia, 2006-22-12. (The copyright holder of this work allows anyone to use it for any purpose including unrestricted redistribution, commercial use, and modification. The image is in the public domain. Photographed in the British Museum, London.)

- Decorated text from the Book of Durrow, beginning of the Gospel of Mark. Illumination on parchment. Ireland or England (Northumbria), c. 650-750 CE. This item is currently held at Trinity College Library, Dublin. Original uploader was Dsmdgold at en.wikipedia, 2005–02-09. (This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art.)

- South Cross, located in Ahenny, County Tipperary, Ireland. Courtesy of Dr. Dorothy Hoogland Verkerk.

- The Kilree Cross, located in County Kilkenny, Ireland. Courtesy of Dr. Dorothy Hoogland Verkerk.

- Map of Ireland, c. 400-1000 CE. Map Recreation Source: Duffy, Sean, Atlas of Irish History, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1997. Courtesy of Dr. Dorothy Hoogland Verkerk.

- Muiredach’s Cross, located in Monasterboice, County Louth, Ireland. Courtesy of Dr. Dorothy Hoogland Verkerk.

Dr. Dorothy Hoogland Verkerk received her Ph.D. in 1992 from Rutgers University, New Jersey. She joined the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1994, where she is now an Associate Professor of Art History. She has published on Late Antique funerary art and illuminated manuscripts as well as the art of early medieval Ireland. Dr. Verkerk is also interested in the fluid and diverse iconography found in early Christian catacombs and sarcophagi with rich references to death rituals. She has also explored Irish high crosses as potential sculptural responses to pilgrimage to Rome. Dr.Verkerk’s book, Early Medieval Book Illumination and the Ashburnham Pentateuch, was recently published by Cambridge University Press. For her class “Celtic Art & Cultures,” Dr. Verkerk has created an online catalog of Celtic art, which can be viewed here: www.unc.edu/celtic.

All images featured in this interview have been cited, and any from Dr. Verkerk have been given to Ancient History Encyclopedia solely for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction of text and images is strictly prohibited. Mr. James Blake Wiener was responsible for the editorial process. Special thanks is given to Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt for her editorial assistance and Ms. Melissa Martin for proving to be the “catalyst” for this interview. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE). All rights reserved. © AHE 2014. Please contact us for rights to republication.