The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, by journalist Joshua Hammer, tells the incredible story of Abdel Kader Haidara — a mild-mannered archivist and historian from the legendary city of Timbuktu — who organized a successful effort to outwit Al-Qaeda and preserve Mali’s greatest treasures in 2012. In this Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) exclusive, James Blake Wiener speaks to Joshua Hammer about Haidara’s life and work, in addition to the importance of Timbuktu’s ancient manuscripts.

JW: Abdel Kader Haidara’s passion for Mali’s ancient manuscripts is at the heart of The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu. Beginning in the 1980s, Haidara crisscrossed the Sahara and Niger River, rescuing manuscripts wherever he could find them. Later, as Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Ansar Dine occupied Timbuktu in 2012, Haidara organized a daring mission to smuggle over 300,000 volumes out of the city.

Joshua, could you share with us an anecdote or two about Haidara and his passion for Malian manuscripts? If anything, he seems to be especially brave and bold!

JH: The clearest illustration of Haidara’s passion is the years that he spent traveling across northern Mali, by boat, on foot, and by camel, tracking down lost manuscripts for the government library in Timbuktu. He initially faced deep suspicion and skepticism; people thought he had come to steal their priceless family heirlooms. Gradually he won them over.

He once trekked for ten days through the desert to a remote village about five hundred miles from Timbuktu, near the Burkina Faso border, following a lead about a village chief with a valuable collection. He waited for several more days for the man to arrive, haggled for two more days with the man and his older brother, then set a price — in livestock and fabrics — and traveled with them to a distant market, where he purchased the goods for them and at last received the trunk filled with manuscripts.

Many of these works were over 500 years old and filled with beautiful designs and original scholarship. He loaded them onto donkeys, and traveled another week back to Timbuktu, on foot, by truck and bus, with his acquisitions. He had spent thousands of dollars, returned fatigued, sick, hungry, and penniless — but he called it the most important and valuable purchase that he had ever made.

“Timbuktu imported academic works from across the Middle East, and also produced thousands of original works. These were not only Qu‘rans and Hadith, the standard stuff of Islamic scholarship, but also secular volumes, including histories, works of poetry, inquiries into music and art, astronomical and medical treatises, even a guide to better sex.” ~Joshua Hammer

Cover for The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu. (Courtesy of Simon & Schuster.)

JW: Why are Timbuktu’s manuscripts of immense importance and what makes them distinct? Furthermore, why would AQIM and Ansar Dine regard them as threatening and subversive?

JH: The manuscripts, many of which come from the “Golden Age” of Timbuktu– — roughly from the late fifteenth century to the late sixteenth century — when the city was not only a vibrant commercial center, but also a university town and an important meeting place for scholars from across the Arabic-speaking world.

Timbuktu imported academic works from across the Middle East, and also produced thousands of original works. These were not only Qu‘rans and Hadith, the standard stuff of Islamic scholarship, but also secular volumes, including histories, works of poetry, inquiries into music and art, astronomical and medical treatises, even a guide to better sex.

They captured the dynamism of Islamic and North African culture during this period, and the seamless coexistence of secular and religious ideas. This kind of open society that they reflected, this tolerant form of Islam that they stemmed from, was considered heretical to the fundamentalist and Wahhabist idealogues who formed the leadership of AQIM and Ansar Dine. They began their occupation by destroying the shrines to Islamic saints where Timbuktu’s Sufi citizens had worshiped for centuries, and eventually they began to set their sights on the manuscripts, as another symbol of “heretical” thinking that had to be eliminated.

JW: AQIM is still active in the Maghreb and across West Africa; although Malians are rebuilding Sufi cemeteries and mausolea in Timbuktu and Gao, the threat of further conflict remains.

What’s the present condition of the surviving manuscripts, Joshua? How are they being preserved, and where are they now? How can ordinary people support efforts to safeguard cultural patrimony in Mali?

JH: Almost all of the manuscripts survived the Islamist occupation. About 377,000 of them have been collected under one roof in Bamako, Mali’s capital, where a Minnesota-based foundation run by a Benedictine monk and ancient manuscript expert, Columba Stewart, is digitizing them and helping to restore those that are disintegrating. He is very much involved in this, traveling to Bamako on a regular basis, and would easily be able to assess what the needs are.

JW: Joshua, it might be impenitent of me to ask this, but what is Haidara up to these days?

JH: Haidara spends his time between Bamako and Europe, overseeing the manuscript conservation effort and trying to raise money, and public awareness, about the collections. Of course he still dreams of returning to Timbuktu, and organizing a massive boat lift down the Niger River, returning all of the manuscripts to the libraries where, he believes, they rightfully belong.

JW: Joshua, thanks so much for speaking with me! It was an immense pleasure.

JH: Thanks James!

Joshua Hammer was born in New York and graduated from Princeton University with a cum laude degree in English literature. He joined the staff of Newsweek as a business and media writer in 1988, and between 1992 and 2006 served as a bureau chief and correspondent-at-large on five continents. Hammer is now a contributing editor to Smithsonian and Outside, a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books, and has written for publications including the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, the Condé Nast Traveler, the Atlantic Monthly, and the Atavist. He is the author of four nonfiction books, including The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, and has won numerous journalism awards. Since 2007 he has been based in Berlin, Germany, and continues to travel widely around the world.

Joshua Hammer was born in New York and graduated from Princeton University with a cum laude degree in English literature. He joined the staff of Newsweek as a business and media writer in 1988, and between 1992 and 2006 served as a bureau chief and correspondent-at-large on five continents. Hammer is now a contributing editor to Smithsonian and Outside, a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books, and has written for publications including the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, Vanity Fair, the Condé Nast Traveler, the Atlantic Monthly, and the Atavist. He is the author of four nonfiction books, including The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu, and has won numerous journalism awards. Since 2007 he has been based in Berlin, Germany, and continues to travel widely around the world.

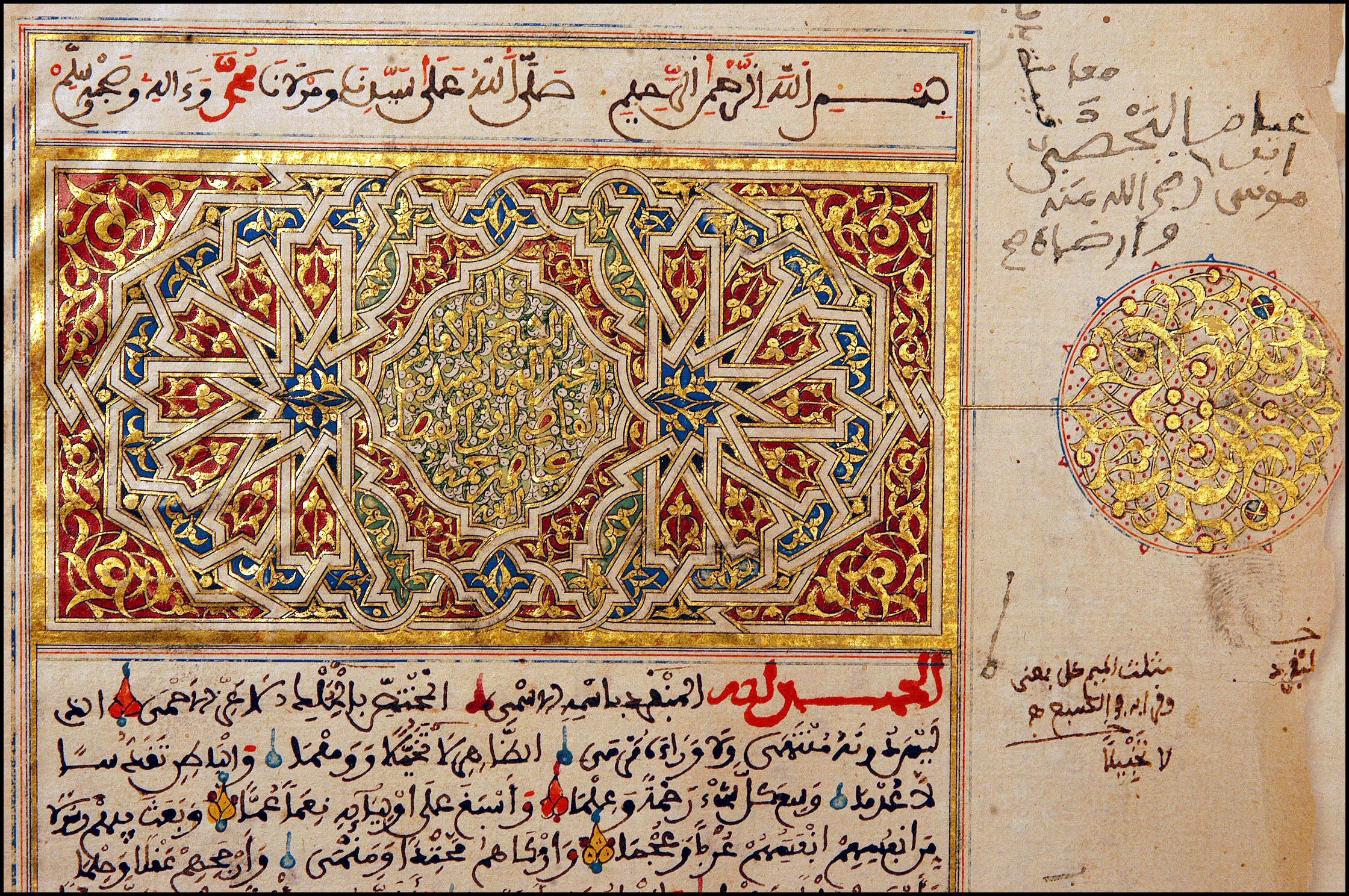

Headline Image: A detailed view on the illumination of a Koran bought in Fes in 1223, for 40 golden mithqals. (Photo by Xavier ROSSI/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.)

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to AHE by Simon & Schuster have been done so as a courtesy. Interview edited by James Blake Wiener for AHE. Special thanks is extended to Ms. Dana Trocker of Simon & Schuster for helping to facilitate this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2016. Please contact us for rights to republication.