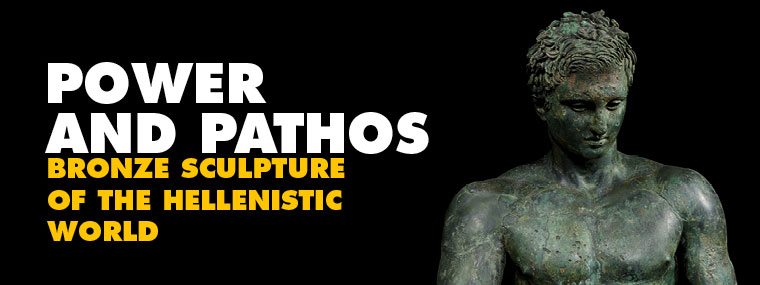

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World underscores the power, prestige, and pre-eminence of ancient sculpture during the Hellenistic Era. This blockbuster show, which opened at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, Italy this spring, is the first major international exhibition to assemble nearly 50 ancient bronzes from the Mediterranean region and beyond in a single venue. Prized over the centuries for their innovative, realistic displays of physical power and emotional intensity, the sculptures of the Hellenistic world mark a key and important transition in art history.

In this interview, Dr. James Bradburne, the recently departed Director General at the Palazzo Strozzi, introduces James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) to the finer points of the exhibition.

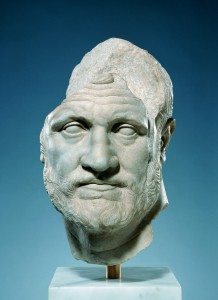

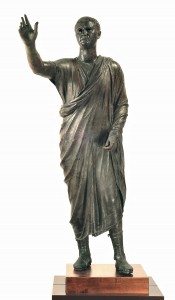

Portrait Statue of Aule Meteli (Arringatore). Late second century BCE bronze 179 cm. Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

JW: Dr. James Bradburne, it is delightful to speak with you and work with the Palazzo Strozzi once more. I’ve been waiting to cover Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World since The Springtime of the Renaissance: Sculpture and the Arts in Florence, 1400-1460 closed two years ago. Welcome back to Ancient History Encyclopedia!

Why has the Palazzo Strozzi organized an exhibition centered on ancient sculpture? Is it because bronze sculptures have been universally celebrated over the centuries and are so rare? It might be noted that Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) considered Corinthian bronze to be more valuable than silver and the equivalent of gold.

JB: It is true that bronzes are rare, not only because the material was precious, but because they more often than not became Roman buttons or Ottoman cannons. Of the 1500 bronze statues made by Lysippos (fl. fourth century BCE), the greatest sculptor in antiquity, none remain — and we are showing well over a quarter of everything that has survived! But we also chose to organize the show for two other reasons: first, it was a chance to collaborate with two international institutions, the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, CA and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., as well as the world-renowned Archaeological Museum in Florence, and second, perhaps even more importantly, the ideas of beauty that gave birth to the Renaissance were based in large part on Hellenistic ones, so it was a great opportunity to show the very wellsprings of Florence’s own past.

Statue Base signed by Lysippos. End of fourth–beginning of third century BCE blue-grey limestone 30 x 70.5 x 70,5 cm. Corinth, 37th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities.

JW: Dr. Bradburne, Power and Pathos is divided into seven carefully arranged thematic units, but visitors entering the exhibition first view the large Portrait Statue of Aule Meteli (Arringatore) — formerly part of the collections of Cosimo I de’ Medici (r 1537-1574) — and Base signed by Lysippos, discovered in Corinth, Greece in 1901.

Why were these two sculptures selected to greet museum visitors as they entered the exhibition? Could you contextualize their importance vis-à-vis the other objects on display?

JB: This very powerful first encounter derives from two things: first, the practice of the Palazzo Strozzi of encapsulating the intent of every exhibition very concisely in one or two objects at the very outset, rather than using lengthy panel texts, and second, a very courageous choice on the part of the curators Ken Lapatin and Jens Daehner of the Getty Museum to acknowledge how little even scholars know about bronzes of this period. So the show opens with a simple, empty pedestal, rather battered, and carrying the inscription ‘Lysippos made this’. Behind it is the famous Arringatore (Orator) from Florence’s Archaeological Museum, one of the rare extant statues of its type, which suggest one possibility — but only a possibility — of what statue Lysippos would have made for the base.

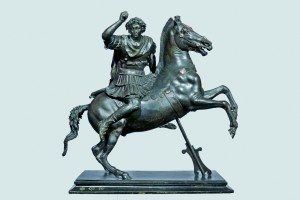

Statuette of Alexander the Great on Horseback. First century BCE bronze, with silver inlays. 49 x 47 x 29 cm. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale.

This conundrum — not even the experts can say with any certainty what stood on the pedestal — also gave rise to the innovative role-playing game The Mystery of the Missing Statue, in which every visitor can choose to explore the show as a curator, a collector, or a forger in order to make a proposal for the lost statue. (The best proposal — as judged by a jury of archaeologists and the curators — will win a trip to Athens, Greece.)

JW: I was curious to know what difficulties you encountered in setting up this show? It appears that many of the items in the exhibition come from other museums from around the world.

JB: The key difficulty of the show was securing the key loans, James. Hellenistic bronzes are extremely rare, and often form the centerpiece of an entire collection, so museums are very reluctant to lend. Fortunately in our case, the collaboration with the Getty and the National Gallery, as well as the extremely important lobbying by the Director General Archaeological Museum in Florence, Andrea Pessina, meant that we were loaned an exceptional number of masterpieces — over a quarter of the works known to be in existence.

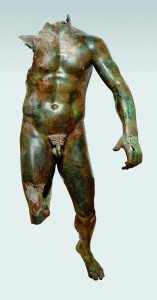

Statue of a Young Man. Third–fourth century BCE bronze 152 x 52 x 68 cm. Athens, Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities.

Moreover, the installation of a sculpture exhibition poses logistical, technical, and conservation challenges that one doesn’t often encounter in other exhibitions, which are often largely paintings. The challenge of installing the works, and to creating a dramatic setting for them without decontextualizing them fell to the designer Luigi Cupellini, who created an unforgettable installation in which the works can be seen not only in context, but viewed from every point of view, with a combination of exhibition lighting and the natural light from the windows of the Palazzo Strozzi.

JW: Why does sculpture, as an art form, continue to beguile us, Dr. Bradburne?

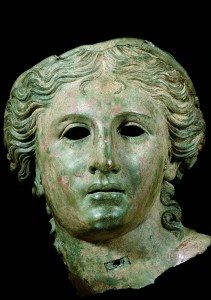

JB: This is a difficult question to answer, and of course the rivalry between painting and sculpture has existed since the beginning, a smouldering tension that has burst into flames at many times, notably in the European Renaissance, when it was a popular topic for courtly debate. Having recently visited Defining Beauty at the the British Museum, which looks at Greek sculpture in all materials in an unexpectedly dispassionate and disconcertingly bloodless way, I was reminded by how much we respond to the pure sensuality of bronze sculpture. I feel that the deliberate patination and unforeseen hazards of time contribute to enhancing the emotional power of Hellenistic sculpture, which is notable for extending the expressive range of sculpture with postures unobtainable in marble and with a depth of human expression often lost in stone.

JW: Something that intrigued me as I explored Power and Pathos was the diverse use and employment of statues across the Hellenistic world: they could be used for votive purposes; displayed in public spaces in which they celebrated personalities or commemorated events; used in a domestic quarters where they fulfilled a decorative function; and finally, they could designate a variety of funerary symbols within cemeteries.

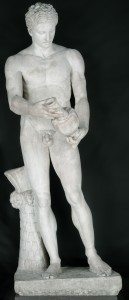

Statue of an Athlete (Ephesos Apoxyomenos type). Second century CE

marble h. 193 cm. Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi.

Of all the statues on display, which among them have visitors commented on with great frequency? Additionally, is there one that you believe best represents the ‘spirit’ of Power and Pathos?

JB: I think the Apoxyomenos from the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria — also the poster image of the exhibition — captures the spirit of the exhibition and is quite popular among visitors. It appears in two versions, the bronze from Vienna and a marble copy from the Uffizi Gallery. Although older, the bronze was reconstructed painstakingly from hundreds of fragments, based on the later Roman marble copy. The juxtaposition is exceptional, visually powerful, and highly instructive.

JW: Dr. James Bradburne, I thank you for speaking with Ancient History Encyclopedia and introducing us to a lovely show. I hope that we shall meet again soon. We now have a history of doing so!

JB: We certainly shall, James. I’m looking forward to it.

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World remains at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, Italy until June 21, 2015. It travels to the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, CA from July 28 – November 1, 2015, and then to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. from December 6, 2015 – March 20, 2016.

Situated between Piazza Strozzi and Via Tornabuoni in the heart of Florence, the Palazzo Strozzi is one of the finest examples of Renaissance domestic architecture. It was commissioned by the Florentine merchant, Filippo Strozzi (1428-1491 CE), and the foundations were laid in 1489 according to a design by Benedetto da Maiano (1442-1497 CE). A year later, the project was given to Simone del Pollaiolo (1457-1508 CE), known as “Cronaca,” who worked on it until 1504 CE, but the Palazzo was only finished in 1538. The Palazzo remained the property of the Strozzi family until 1937, and it has been managed by the city of Florence since 1999. Following the Second World War, the Palazzo became Florence’s largest temporary exhibition space. Several of the notable major exhibitions held at Palazzo Strozzi have been The Peggy Guggenheim Collection (1949), 17th century Florence (1986), Gustav Klimt (1992), La Natura Morta Italiana (2003), Botticelli & Filippino Lippi (Italy’s most visited exhibition in 2004), Leon Battista Alberti (2006), and Cézanne in Florence (2007).

Situated between Piazza Strozzi and Via Tornabuoni in the heart of Florence, the Palazzo Strozzi is one of the finest examples of Renaissance domestic architecture. It was commissioned by the Florentine merchant, Filippo Strozzi (1428-1491 CE), and the foundations were laid in 1489 according to a design by Benedetto da Maiano (1442-1497 CE). A year later, the project was given to Simone del Pollaiolo (1457-1508 CE), known as “Cronaca,” who worked on it until 1504 CE, but the Palazzo was only finished in 1538. The Palazzo remained the property of the Strozzi family until 1937, and it has been managed by the city of Florence since 1999. Following the Second World War, the Palazzo became Florence’s largest temporary exhibition space. Several of the notable major exhibitions held at Palazzo Strozzi have been The Peggy Guggenheim Collection (1949), 17th century Florence (1986), Gustav Klimt (1992), La Natura Morta Italiana (2003), Botticelli & Filippino Lippi (Italy’s most visited exhibition in 2004), Leon Battista Alberti (2006), and Cézanne in Florence (2007).

Dr. James M. Bradburne is a British-Canadian architect, designer, and museum specialist who has designed World’s Fair pavilions, science centers, and international art exhibitions. Educated in Canada and England, he has developed numerous exhibitions, research projects, and symposia for UNESCO, UNICEF, national governments, private foundations, and museums worldwide over the past twenty years. He currently sits on numerous international advisory committees and museum boards, and has curated and designed exhibitions across Europe. James lectures internationally about new approaches to informal learning and has also published extensively. Formerly, James was the Director General at the Palazzo Strozzi. To learn more about James’ work, education, and interests, please view his CV.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Ms. Rosanna Wollenberg, Account Director, Brunswick Arts, for helping facilitate this interview. Additional thanks is extended to Ms. Lavinia Rinaldi, Press Office and Public Relations at Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.