Masks were used for a wide variety of purposes across many ancient cultures. Some of the most common purposes were as funerary masks for important persons, as protection in warfare, worn during theatre performances, or to be worn by impersonators of gods during religious ceremonies. Materials were typically of high value such as gold, jade, and turquoise. This collection spans some 3,000 years from Egypt to the Americas.

Egyptian Masks

Egyptian gold coffin mask of queen consort of king Djehuti (around 1650 BCE). Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst (State Museum of Egyptian Art) in Munich, Germany. Photographer: Ali Kalamachi.

Plaster inlaid with stone Egyptian funerary mask from 3rd to 4th century CE. Egyptian Museum, Castello Sforzesco, Milan, Italy. Photographer: Mark Cartwright.

The death mask of Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun. The mask is made of gold, precious stones and glass inlay, 14th century BCE. Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt. Photographer: Richard IJzermans.

Greek Mask

The so-called death mask of Agamemnon – the king of Mycenae in Homer’s Iliad.

Gold funeral mask from Grave Circle A, Mycenae (mid-16th century BCE). The mask in fact predates Agamemnon by 400 years but, nevertheless, remains solid evidence of Homer’s description of Mycenae as ‘rich in gold’. National Archaeological Museum, Athens. Photographer: Xuan Che.

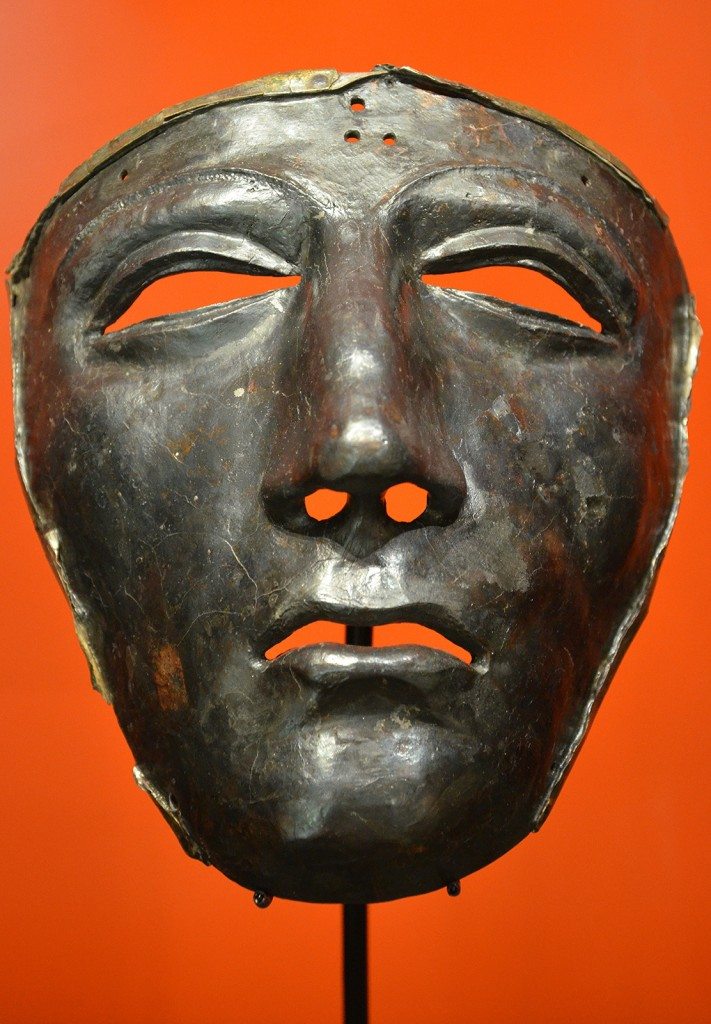

Roman Masks

This military face mask (thought to have been worn in battle and during parades by cavalry) is one of the most exceptional finds at the site of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest. It is one the oldest facial helmets known in the Roman army, dating from the first part of the 1st century CE. Museum und Park Kalkriese, Germany. Photographer: Carole Raddato.

Golden Cavalry Face-Mask Helmet (Type Ribchester) dating from 80-125 CE, found on the bed of the Corbulo Canal (Fossa Corbulonis) near the Roman fort of Matilo (modern Leiden). Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. Photographer: Carole Raddato.

Cavalry Face-Mask Helmet (Type Nijmegen-Kops Plateau), brass sheet on iron core, dating to the 1st or 2nd century CE. Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden, Netherlands. Photographer: Carole Raddato.

Americas Masks

A mask of jadeite from the Olmec civilization of the Gulf coast, Mesoamerica, 900-500 BCE. Provenance: Rio Pesquero, Mexico. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, USA. Photographer: Mary Harrsch.

A Moche gold mask/headdress (1-700 CE). The figure represents a fanged deity, a common subject in Moche art. Larco Museum, Lima, Peru. Photographer: Lyndsay Ruell.

A beaten gold mask from the Nazca civilization of Peru, 200 BCE-500 CE. 18.4 x 20.5 cm. The mask may represent a shaman in transformational pose, a common motif in Nazca art. An alternative interpretation is that it represents the weeping sun deity common to several ancient Andean cultures. Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, USA. Photographer: Wikipedia User: FA2010.

A turquoise mosaic mask representing Xiuhtecuhtli, the Aztec god of fire, 1400-1521 CE. The mask is of cedar wood with mother-of-pearl eyes, conch shell teeth, and once had gold leaf on the eyelids. The British Museum, London. Photographer: British Museum.

A gold-sheet mask representing the sun god Inti from the La Tolita part of the Inca empire. The design is typical of masks of Inti with zig-zag rays bursting from the head and ending in human faces or figures. National Museum, Quito, Ecuador. Photographer: Andrew Howe.

For information on the image rights in this collection, please click on each photographer’s name within the image caption. All images can be seen on the Ancient History Encyclopedia website.