Although mentioned several times in the Biblical texts, the actual existence of the Hittites was largely forgotten until the late 19th century. With the discovery of Hattusa in 1834, the city that was for many years the capital of the Hittite Empire, the Hittites were finally recognized as one of the Great Superpowers of the ancient Middle East in the Late Bronze Age.

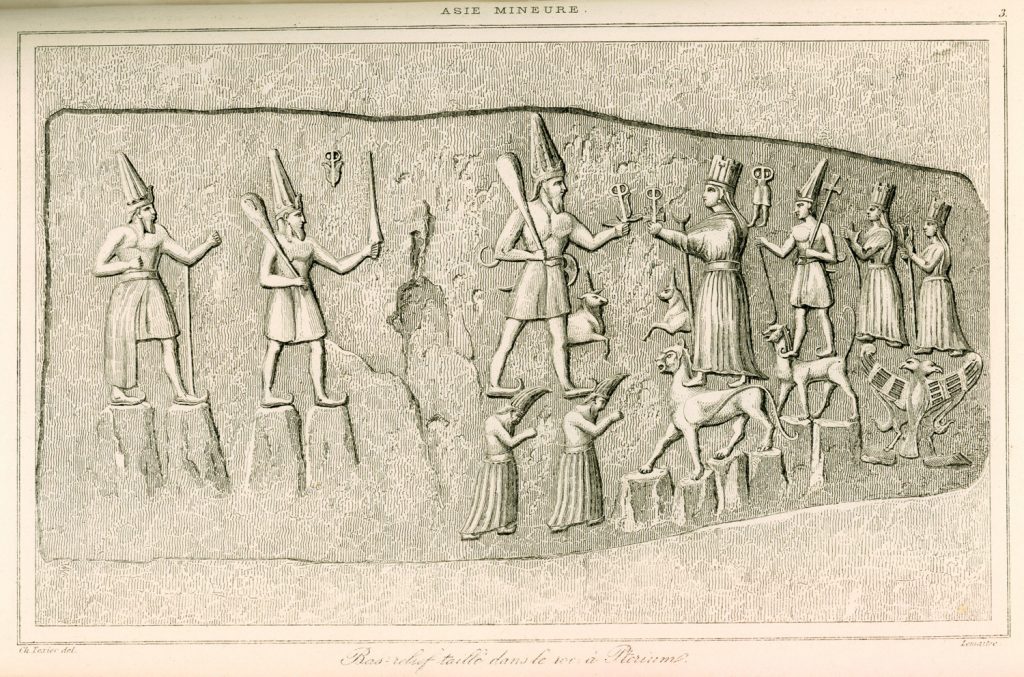

Engraving from a relief at Yazilikaya by French archaeologist Charles Texier (1882). Teshub stands on two deified mountains (depicted as men) alongside his wife Hepatu, who is standing on the back of a panther. Behind her, their son, their daughter and grandchild are respectively carried by a smaller panther and a double-headed eagle.

They populated the broad lands of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) originally occupied by the Hatti and later expanded their territories into northern Syria and as far south as Lebanon. The Hittite language, which was written in both cuneiform script and hieroglyphics, is believed to be the oldest of the Indo-European languages and was deciphered only in 1915. Religion played an important role in Hittite life. The Hittites worshiped so many deities that they referred to them as “the thousand gods of Hatti”. At the center of the Hittite pantheon were the Storm god Teshub and his wife the Sun goddess Hebat.

The Hittite kingdom reached its greatest extent during the mid-14th century BCE under Suppiluliuma I and his son Mursilli II. The collapse of the kingdom around 1200 BCE drove the Hittites south where they created a series of Neo-Hittite city-states north and east of Adana. Some of these lived on into the 8th century BC before vanishing from the pages of history.

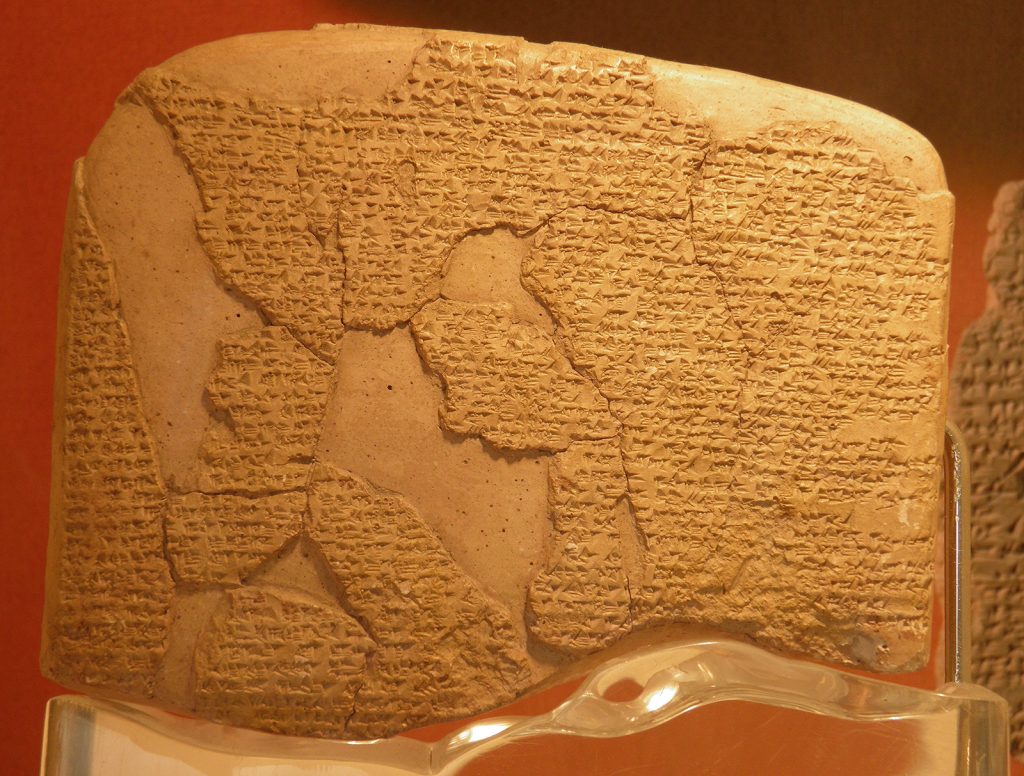

The rediscovery of the Hittites has been one of the major achievements of archaeology of the last century. Its capital Hattusa has since been declared a World Heritage site by UNESCO. An enlarged copy of a cuneiform clay tablet found at Hattusa hangs in the United Nations building in New York. This tablet is a piece treaty signed between between the Hittite and Egyptian Empires in 1258 BCE after the famous Battle of Kadesh. It is the earliest peace treaty whose text is known to have survived.

“Reamasesa-Mai-amana, the great king, the king of the country of Egypt, shall never attack the country of Hatti to take possession of a part (of this country). And Hattusili, the great king, the king of the country of Hatti, shall never attack the country of Egypt to take possession of a part (of that country).“

The Hittite version of the Egyptian–Hittite peace treaty (Treaty of Kadesh), discovered in 1906 at Boğazköy (Turkey), 1259 BCE. (Istanbul Archeology Museum)

The most impressive Hittite remains are scattered between Çorum, north-east of Ankara, and Kayseri on the eastern fringes of Cappadocia. On my last trip to Turkey I ventured off the beaten track to discover the land of the Hittites and explored their cities, citadels and religious centers. I have compiled a list of the five most important Hittite settlements.

Hattusa

Hattusa was the capital city of the Hittite Empire. It is located in the Boğazkale District of the Çorum Province, 150 kilometres east of Ankara. The ruins of the city walls, the gates, the temples and the palaces awaiting the visitors today provide a comprehensive picture of the Hittite capital in the 13th century BCE.

At its peak, the population of Hattusa reached an estimated 40,000-50,000 inhabitants. The city was very large, covering 1.8 km² with massive defensive walls over 6km in length and huge watchtowers and secret tunnels.

Modern reconstruction of a 65m long section of the city wall made of mud brick with defense towers built at intervals of 20-25 metres. The reconstructed part rests on top of the original Hittite foundations. The inner city wall shielded the area of the Great Temple and adjacent settlement.

The site was discovered on July 28 in 1834 by Charles Texier but the first systematic excavations in Hattusa began in 1893-1894 under the guidance of Ernest Chantre who published the first cuneiform tablets from Hattusa. Since 1907 archaeological work has been carried out by the German Archaeological Institute. The city consisted of two separated districts; the Lower City, the district of the Old City of the Hittites where the main temple was located, and the Upper City, a newer part of the city with a fortified palace complex surrounded by massive walls. The site also boasts a number of hieroglyphic inscriptions bearing traces of the so-called “Luwian” script.

The six-line Luwian hieroglyphs inscription commissioned by the Great King Suppiluliuma II on the right-hand wall of the chamber. The text describes the invasions and successes of King Suppiluliuma II, mentioning that with the help of the gods, the King invaded several lands, including that of Tarhuntassa.

The city was destroyed, together with the Hittite state itself, around 1200 BCE, as part of the collapse of the Late Bronze Age kingdoms. Excavations at the site revealed that Hattusa was invaded and burned early in the 12th century BCE after many of Hattusa’s residents had abandoned the city. The site was subsequently abandoned until 800 BCE when a modest Phrygian settlement appeared in the area. Today the whole tour of the ancient city can be completed following the concrete path of 3-4 kilometers either on foot or by car.

The King’s Gate situated at the southeast of the city fortifications with a sculpture of the God of War in high relief measuring 2.25m in height. The original relief can be seen today in the Museum of Ancient Civilizations in Ankara.

The Sphinx Gate standing above the Yerkapi Rampart. Unlike the Lion Gate, the Sphinx Gate was not flanked by towers but led through a tower. All four door jambs bore representations of Sphinxes. Only one original Sphinx is still in place while two others are kept in the local museum.

The Temple District in the Upper City. 24 different sacred buildings have been identified, they vary greatly in dimensions.

Yazilikaya

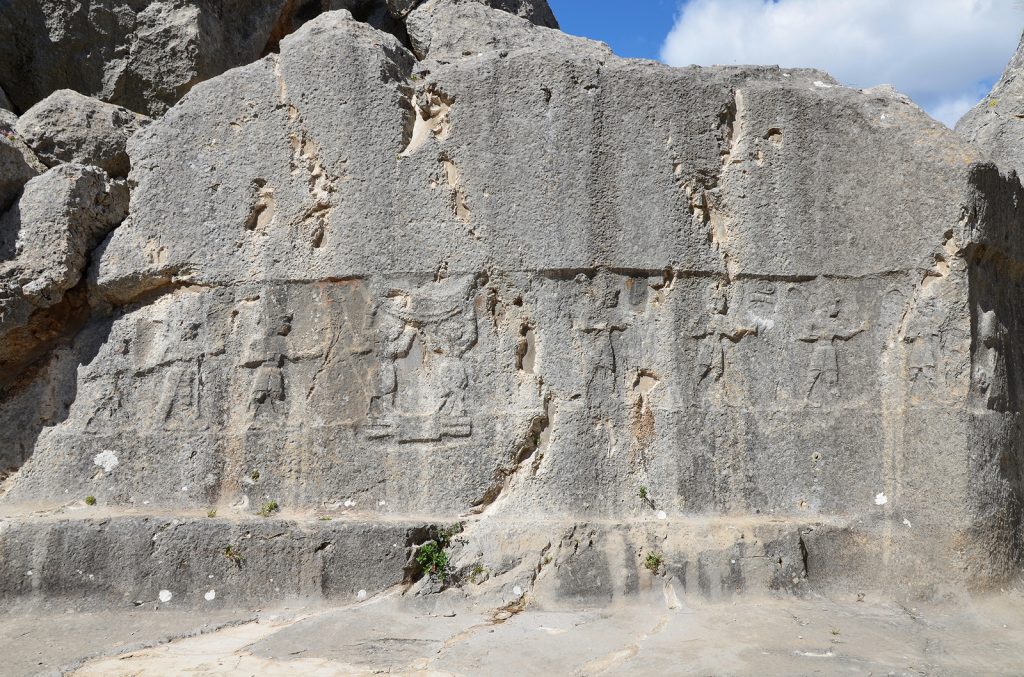

Yazılıkaya (“Inscribed Rock”) is a Hittite rock sanctuary located about 1.5 kilometers northeast of Hattusa. It is the largest known Hittite rock monument. The sanctuary consisted of a temple-like building and two open-air chambers cut into the bedrock.

The Yazılıkaya sanctuary served as a place for the celebration of the arrival of the New Year each spring. These ceremonies took place in the open air in front of the Hittite Pantheon. The sanctuary was made of two rock chambers, later labelled Chamber A and Chamber B by archaeologists. The walls of each chamber was covered with the richest and most striking samples of Hittite relief art. They featured gods and goddesses and the figures of the Great King Tudhaliya IV (ca. 1237 – 1209 BCE). There are a total of 83 images, 66 in the Chamber A and 17 in Chamber B.

Human activity on the site probably began in the 16th century BCE, although what we see today is probably the result of modifications made in the late 13th century BCE, not long before the Hittite Empire began its steep and mysterious decline.

Chamber A, twelve gods of the Underworld. They all wear shoes curling up at the toe, and many are armed with either a sickle-shaped sword or a mace, which they carry over their shoulder.

Chamber A, two bull-headed men stand between male gods on the hieroglyphic symbol of the earth and supporting the sky.

The main scene in the middle of Chamber A is depicting Teshup and Hepat meeting as well as female goddesses in procession on the right wall.

Chamber B is accessible via a narrow passage with winged demons on both sides. It is believed that Chamber B was built as a memorial chapel for Tudhaliya IV, dedicated by his son Suppiluliuma II at the end of the 13th century BCE. Buried until the mid 19th century, the reliefs on the walls are much better preserved than those in Chamber A. A line of gods of the Underworld are pictured on the wall immediately to the right of the entrance. On the opposite wall is a representation of Nergal, the God of the Sword and the Underworld. To the left of this relief a cartouche with the name of Tudhaliya IV is visible and this same king is shown embracing the Thunder God Teshub on the right side.

Chamber B. The narrow gallery is thought to be a memorial chapel for Tudhaliya IV, dedicated by his son Suppiluliuma II.

East wall of Chamber B depicting in a niche the God Sharruma (son of the Thunder God Teshub) embracing King Tudhaliya IV. The god has his left arm over the king’s shoulders while holding the king’s right wrist. The god wears a shot tunic and has pointed shoes. The king wears a long coat and carries a sword and a litus.

Alacahöyük

Alacahöyük was the center of the flourishing Hattian culture during the Bronze Age. It was later occupied by the Hittites who used the city as their first capital before moving over to Hattusa. The site is located in Alaca, northeast of Hattusa.

Alacahöyük was discovered in 1835 by the English voyager W.G. Hamilton. The first excavations started in 1861 by French archaeologist George Perrot but more extensive work was initiated by the Turkish Historical Association in 1935 and continued until 1948. Since 1997, the excavations have been carried out by Ankara University under the direction of Prof. Dr. Aykut Çınaroğlu.

The excavations revealed fifteen layers of settlement buried under the soil dating back to 5500 BCE to 600 BCE. The richest and most important layer belongs to the Early Bronze Age. Many treasures have been excavated from the thirteen Hattian royal tombs dating to the 3rd millennium BC. Among these artifacts were bronze sculptures of bulls or deer, ceremonial symbols and sun disks. These artifacts are housed today in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.

The area of the Royal Tombs built in the Early Bronze Age (2500-2000 BCE). They had a major role in our understanding of the indigenous Hattian Civilization. Six out of thirteen intramural tombs have been reconstructed to their original appearance.

Bronze sun disk encircled with bull and deer figures, the sacred animals of the Hattians, found in Alacahöyük, 2500-2250 BCE (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara).

However most of the standing remains at Alacahöyük, such as the “Sphinx Gate”, date from the Hittite period that followed the Hattians (1460-1200 BCE). At that time the city was surrounded by a mud brick wall with a stone base. The “Sphinx Gate”, fortified with towers, was the main gate of the city. It was flanked by two sphinx protomes with, in its inner parts, a relief depicting a double-eagle holding rabbits in its claws. These sphinxes were the protectors of the city.

The Sphinx Gate, built in the 14th century BCE, has a 10m width. The exterior faces of the large post blocks flanking the gate entrance were adorned with two-metre tall sphinx protomes.

The inner face of the eastern sphinx protome decorated with a double-headed eagle engraved as a low relief, over the eagle holding rabbits in its claws, legs of a goddess walking towards the city can be seen, 14th century BCE.

The lower parts of the towers were decorated with orthostat reliefs depicting a religious ceremony including a king and a queen praying to a bull before an altar, a lion hunt, animals being sacrificed as well as jugglers and acrobats. These depictions represented an entire ritual set of cult, libation, hunting and entertainment that included a religious ceremony in honor of the Storm God. The original reliefs are on display in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.

The external facade of the western tower located in front of the Sphinx Gate ornamented with relief-decorated orthostates depicting a religious ceremony in honor of the Storm God.

Kültepe

Kültepe, located 18 km northeast of Kayseri and formerly known as Kanesh and Karum, was part of the network of trading settlements established in central Anatolia by Assyrian merchants from Ashur (northern Mesopotamia) in the early 2nd millennium BCE. This period was called the “Assyrian Trading Colonies Period“. During this time, the Assyrians were very active in international trading. Assyrian merchants sold tin and textile products in exchange for precious metal like gold, silver and copper. Later on, the Hittites inhabited the city which they called Neša and made it their first capital. The site is composed of two parts; the lower town Karum and the upper mound Kanesh.

The ruins of Karum, the capital trading center of the Assyrian merchants in Anatolia in the first quarter of the 2nd millennium BCE.

Anatolia entered recorded history in Kültepe as it is the site of the discovery of the earliest written documents in Anatolia. Assyrian merchants documented and recorded their transactions on clay tablets in the ancient Assyrian dialect using the cuneiform script. Thousands of these texts stored in household archives were preserved when fire destroyed the city in ca. 1836 BCE. Today, the clay tablets found at Kültepe provide a glimpse into the complex and sophisticated economic, political and social interactions that took place during the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE.

Clay tablets with cuneiform letters found Kültepe (ancient Kanesh), 1900 BC – 1700 BCE.

They were all written by merchants who, from around 1900 BC, had come to Kanesh from the city of Ashur in Assyria and established a karum (trading center). Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara.

These clay tablets also provide valuable information about the early Hittites. Among the local rulers who settled in Kanesh was Anitta, the earliest known ruler to compose a text in the Hittite language (and the oldest known Indo-European text).

The ruins of Warsama’s palace, King of Kanesh, the upper mound Kanesh. This palace is one of the oldest examples of the Anatolian/Hittite palaces dating back to 1800-1750 BCE.

Sapinuwa

Located in Ortakoy, 53 kilometres southeast of Çorum, Sapinuwa was an important Hittite military and religious center. The city was established in a long valley between Alacahoyuk and Hattusa, along the east-west trade route leading to Middle Anatolia. Sapinuwa was also the residence of several Hittite kings and for some time the capital city of the Empire.

Sapinuwa was mentioned on cuneiform tablets unearthed during excavations at Hattusa but its location was not localized until 1989 when a farmer found clay tablets while ploughing his field. The excavations at the site began the following year in 1990 on behalf of Ankara University. The site has yielded an archive of about 4,000 tablets and tablet fragments dating back to the beginning of the 14th century BCE.

The ruins of Sapinuwa are spread out over 9 km2 and include many building foundations. A monumental structure with Cyclopean-walls, the so-called “Building A”, was uncovered at the site. It was a three-story building used for administrative, religious and commercial purposes. The other structures discovered include a warehouse for large jars where grain, wine and olive oil were stored. A street that lies in a north-south direction with workshops on one side was also unearthed. Some of the Sapinuwa finds are on display in the Museum of Çorum.

Sources:

- Hattusha Guide: A Day in the Hittite Capital by Jurgen Seeher (Ege Yayinlari; 4th ed. edition, 2011)

- Anatolia: On The Trail of the Hittite Civilization by Nurhayat Yazici (Uranus, 2011)

- The Hittites and Their Contemporaries in Asia Minor by J.G. MacQueen (Thames and Hudson, 1996)