Today we have another contribution from Time Travels Magazine in which Ben Churcher writes about the remains that can be found of the Persian wars in Greece.

The road from the Plain of Marathon to downtown Athens is, as we all know, around 40 km due to the length of the modern marathon that supposedly commemorates a run undertaken in 490 BCE to announce to the Athenians that they had defeated the Persians. First, to put one thing straight, the runner was not, as the eminent scholar tells me, made by a Greek soldier Pheidippides. Pheidippides was not a soldier but a professional long-distance runner who, a few days before the Battle of Marathon, made a run from Athens to Sparta where he reached Sparta the day after he left Athens. Secondly, common belief has it that when the runner reached Athens to announce the victory that he collapsed and died after delivering his message. Again this is wrong.

The mighty Persian Empire went to war with Greece on three occasions during the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. Ben Churcher follows in the footsteps of those invading armies and sees what is left of those battle grounds today.

Our primary ancient source for the Persian Wars, the historian Herodotus, fails to mention either a runner going from Marathon to Athens and certainly not that he died on reaching his destination. Anyone who knows their Herodotus would find it incredulous that such a vivid story was omitted from his history and so it seems that, 2,500 years later, we have woven a myth of Pheidippides running from Marathon whereas in fact, in all likelihood, no such run ever occurred.

And don’t get me started on the historical reality of recent films such as 300 that again piles on the myth when talking about another famous battle of the Persian Wars: Thermopylae. Films of buffed and tattooed warriors purporting to be ancient Greeks belong in the reject aisle at the local video store rather than being in any way connected to historical reality!

To sort myth from reality, I’ve had the pleasure to travel to many of the locations where the main engagements of the Persian Wars took place. If nothing else, it was a chance for me to travel off the beaten track while in Greece and Turkey but it has also allowed me to better visualise the scenes described by Herodotus so evocatively as he recorded a time, as he says, when “men fought in a way not to be forgotten”. What more could a young man travelling around Greece wish for?

Battle of Marathon

The road to Marathon from Athens – even without epic runs – is uninspiring. The first half snakes its way through outer Athens before you climb a hill and have the Plain of Marathon spread out below you. The plain is dotted with

This article was originally published in Timeless Travels magazine. Republished with permission.

villas, and a swamp, that once existed at the northern end of the plain, has long-since been drained (ironically being re-filled for the rowing events of the Athens Olympic Games). Yet, of all places, this plain is pivotal to western civilisation for it was here that the city of Athens, virtually alone, defeated the mighty Persian army. With the loss of 192 soldiers and relying on the tactics of the general Miltiades, the Athenians on this plain smashed Persian hopes for revenge and conquest.

This event catapulted Athens into being one of the leading cities of Greece and ushered in the Golden Age of Athens when democracy became firmly entrenched, theatre was developed, histories written and philosophy encouraged. If Athens had lost at Marathon who knows what may have happened but one thing is certain: there is no way under Persian domination that Athens could have flowered as it did and bequeath to the rest of us the pillars of western civilisation.

When arriving at Marathon, I’d recommend heading straight to the small archaeological museum that is located near the Tumulus of the Plataeans (the only other Greek city to aid Athens at Marathon). It was in the hills above the museum where the Greeks made their camp. Here they waited out the Persians, hoping against hope, that Sparta or the other powerful Peloponnesian cities would come to their aid.

In the end it was realised that no help was coming and when Miltiades saw his opportunity he ordered his forces to literally run at the enemy. You can take the small road behind the museum and climb the first foot slopes of the hills. Here you have a panoramic view of the battlefield and can well imagine the Greek troops pouring past you: each soldier knowing that they were going up

against the most sophisticated and powerful empire the world had yet seen. Indeed, as Herodotus tells us, up till that time no Greek could even hear the mention of ‘Persia’ without being afraid.

Yet, because the Greeks had noted that the Persians had embarked their fearsome cavalry on board their transport ships, they realised they stood a chance, and pouring out of the hills, ran to the Persian lines that had been drawn up in the middle of the plain.

The remains today

I would now suggest that a modern visitor retrace the route of the Greeks and head to the Athenian tumulus that is preserved in the middle of the plain at the location where the main engagement took place.

Normally the Greeks did not bury their dead on the battlefield but such was the honour given to the fallen at Marathon

that a huge mound of earth was raised over their cremated remains. While all one sees today is a small grassed hillock, you can imagine the scene here in 490 BCE when the Greek and Persian lines first met. Miltiades intentionally kept his centre lines weak so that the best Persian troops, also in the centre lines, forced back the Greek centre. Miltiades, however, had strengthened the wings of the Greek army and they held their ground. Eventually the two wings of the Athenian army came together and encircled the Persian infantry.

Those Persians that escaped the rout made their way to the nearby beach where Persian ships tried to evacuate them. Herodotus tells us that a fierce battle raged on the beach until the Persian fleet made its escape but not without sustaining severe casualties. The beach, naturally, is still there but is today lined with tavernas and cafes.

After your visit to Marathon it is a good place to finish, have a drink and watch the shallow waves of the Aegean lapping against the sand. In your mind’s eye you can imagine the bedlam here at the end of the battle: Persians, wide-eyed with terror doing anything possible to clamber aboard a ship while resolute Greeks closed in around them.

Without sending a runner to Athens first, the entire army marched in quick time back to their city as it was feared the Persians were going to sail around Cape Sounion and attack the city. The Greeks made it there first and when the Persian ships arrived they saw the Acropolis defended and dejectedly sailed for home. The second Persian invasion was at an end.

Crossing the Hellespont

It took 10 years of preparation but in 480 BCE the Persians were ready to try again. This time, nothing was left to chance. The Persian troop numbers were colossal and included the legendary 10,000: the Persian elite troops. Overseeing them all was the Persian king himself, Xerxes.

The first obstacle that needed breaching was the Hellespont; a narrow strait of water separating Europe from Asia known today as the Dardanelles. Herodotus tells us that Xerxes ordered two bridges to be built across the Hellespont: not by the usual methods of rigging ships together but by using flax and papyrus ropes as ‘thick as a man’ as the main support structure. After the bridges were complete, a severe storm blew down the Hellespont and the bridges were destroyed. Xerxes was furious and he had the hapless engineers beheaded before ordering the royal executioner to the shores of the Hellespont where he was to whip the waters and each time say “you salt and bitter stream, your master lays this punishment upon you for injuring him”.

Such high drama! But all things pass and today the site of Xerxes’ bridges is just another small beach along the Hellespont. The bridge spanned the Hellespont at one of its narrowest points opposite the Greek city of Abydos where it is still over a kilometre-wide. The site can be easily reached on the European shore from a road that hugs the shore of the Dardanelles. In an environment of conifers and rock you can walk less than 50 metres from the road to the shore, stepping around rubbish, until you reach the narrow beach, again with the plastic flotsam from a dozen nations washed ashore. Between you and the far shore Russian oil tankers sluggishly churn against the current as birds wheel overhead. The current is swift and the distance far enough to stretch your incredulity that once, 2,500 years ago, it was possible to bridge such a distance.

After the failure of the first bridges, Xerxes ordered two new bridges to be constructed in the more traditional manner of lashing ships together. Once complete, as Herodotus tells us, for seven days and seven nights the army of the Persians crossed the bridges into Europe hell-bent on teaching the Greeks a lesson.

Digging a canal

Among the many vestiges of Xerxes’ power which survive today is the remains of the canal he had dug across the Athos peninsula. The first Persian invasion in 492 BC—under Xerxes’ predecessor—King Darius, had been stopped in its tracks when the navy was destroyed in a wild storm as it tried to round the Athos Peninsula: the eastern most promontory of the Chalkidiki in northern Greece. This, combined with King Darius’ later defeat at Marathon in 490 BC, made Xerxes leave nothing to chance.

The king ordered that a canal be cut across the narrow neck of land at the base of the peninsula, wide enough for two warships to be rowed abreast. With this canal in place, his ships could safely pass to the west, without making the dangerous journey around the end of the peninsula.

This was all grandstanding of course—perhaps with a bit of superstition thrown in—as the canal cannot be seen as any form of strategic imperative. But Xerxes was not to be deterred by such matters.

You can follow much rusted signs to eventually track down what remains of Xerxes’ canal today located just north of the territory owned by the Orthodox Church that occupies most of the Athos Peninsula. On its eastern side is a small settlement made up of refugees who fled Asia Minor in the 1920s. Now the place is a rather run down Greek beach resort: dotted about are little sheds with ‘DISCO’ painted in whitewash on the wall and steel frames, which once had canvas on them, rust on the beach.

Not much can be seen of the canal at this eastern end as the beach has filled in the landscape considerably. When you turn inland, however, and head to the west, the gradual contours of the original construction become clearer. At its best, the canal today is nothing more than a small valley in the landscape: overgrown with vegetation and divided up into cattle paddocks. Quiet, unvisited and slowly but surely blending in with the surrounding landscape: one can only imagine how different the scene was prior as Xerxes’ forces used the canal in their westward march.

Spartan bravery

With the advance of Xerxes, the southern Greek cities came together, for one of the few times in their history, to discuss what to do. The Spartans, from one of the oldest and certainly the most militaristic cities in Greece, argued that the next line of defence should be the Isthmus of Corinth.

Fine strategy for the Peloponnesian cities as the Isthmus is easily defended but it would have meant abandoning cities such as Athens and Thebes to the north of the Isthmus. Naturally this did not go down well with the Athenians who threatened to go over to the side of Persia if the Peloponnesian cities did not make an effort to defend all of Greece, not just their home patch. The danger of Athens, and particularly the Athenian navy, being in the employ of the Persians was enough for the southern cities to agree to keep Athens in the Greek league and defend the next best spot: the pass at Thermopylae.

We hear a lot about the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae but we also need to remember that there were troops from other cities at Thermopylae, at least until just before the end, and that Athens played a pivotal role with her navy in stopping the southern advance of the Persian fleet that would have been able to outflank the Greeks at Thermopylae if unhindered.

But this is not to take anything from the Spartans who did, under their king Leonidas, defend the pass to the death and rightly earned for their city the reputation for Spartan bravery and the fact that a Spartan would never surrender.

It is relatively easy to get to the pass of Thermopylae today as, until recently, the main road between Athens and Thessaloniki passed within metres of where the action took place. Now by-passed by a motorway, traffic through the pass has lessened but the road is still there and the location of the main battle marked by a recent statue of a Greek hoplite, or infantryman, with his spear held high.

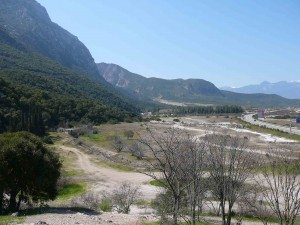

What is needed at Thermopylae, however, is a fair bit of imagination as the location today does not look anything like a narrow pass. This is due to the fact that local rivers have deposited a lot of alluvium over the millennia and has in-filled the Malian Gulf to the extent that you can hardly see the water when at Thermopylae. Instead, you have to imagine the water coming right in to where the road is today, leaving a narrow pass between the hills to the south and the water to the north. With a small amount of flat land in front of the pass that still contains a hot spring that gives the place its name and a wall built to protect the pass, this was a perfect location for the Greeks to nullify the Persian numerical superiority and hold up their southward advance.

Thermopylae hills and plain: scene of Spartan bravery. Photo © Fkerasar, under license Wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0

Like most battlefields, there is not a lot to actually see at Thermopylae but if you have a copy of Herodotus with you the place comes alive. You can see (in your mind’s eye) the Spartans combing their long hair as they prepared to die, the Persian officers whipping their men to keep them advancing against the Greeks, the tussle over the body of the fallen Leonidas and

the last, desperate stand on top of a small hillock directly opposite the modern memorial. Here Herodotus tells us, the last of the Spartans fought to the death with their swords if they had them, with their teeth and nails if they didn’t. They fell to a man and at the location of their last stand is a modern reproduction of the ancient memorial that says, with typical

Spartan lugubriousness, “Go tell the Spartans, you who read: We took their orders, and here lie dead”. It is not uncommon to find a bunch of flowers on this memorial: testimony of the never-ending power of this battle when the Greeks gave their all to defend themselves against the storm from the east.

Athens is destroyed

With the Spartans vanquished at Thermopylae, the Persians streamed south into the heartland of Greece. Following advice from Themistocles, the Athenian leader, most of the Athenians abandoned their city and fled to the nearby island of Salamis. Apart from a few fool-hardy souls who insisted on defending the Acropolis, the deserted city was easily captured by the Persians who had their revenge for their defeat at Marathon 10 years earlier by putting the city to the torch.

There is still evidence of this destruction when you visit Athens today. When in the Plaka, the pleasant district of Neo-Classical buildings, shops and restaurants nestled under the Acropolis, you can look up at the Acropolis and notice that a number of column drums have been built into the perimeter wall that crowns the cliffs. These drums came from the partially-built Parthenon that the Persians destroyed and were later used as ready raw material when the Athenian leader, Themistocles, hurriedly fortified Athens following the Persian Wars.

On the Acropolis itself, just after you’ve exited the monumental gateway or Propylaea and approach the back of the later, and more well-known, Parthenon you will notice that the stylobate (or base) of the Parthenon has been built from two different types of stone. The lower, greyer and more weathered, was the stylobate of the original Parthenon destroyed by the Persians while the lighter coloured stones on top date to later in the 5th century BCE when the Parthenon was rebuilt during the time of Pericles.

However, for the best evidence of the Persian sack of Athens, you need to visit the new Acropolis Museum that has been purpose-built at the foot of the Acropolis. This superb museum should be on the itinerary of every visitor to Athens, and when there, take note of the Korai and Kouroi that have been spread across the lower floor.

These votive statues of young women and men have been placed so that you can move around and between them giving you a marvellous feeling of literally being immersed among the youth of ancient Athens. Many of these exquisitely carved statues have fragments of the original paint that once covered them: a rare reminder that ancient statues were not always bleached white. They do, however, show damage: faces cropped off, arms lost, hack marks at the back of the head. Many of these statues were found buried in a pit on the Acropolis where they had been reverently placed by the Athenians following the clean-up of their city following the Persian destruction. This preserved their original colouring, and while the damage made by the marauding Persians is manifest, their ‘destruction’ has preserved for us some of the most delightful sculpture from late 6th century BCE Athens.

Persian retreat

Marathon. The tumulus raised over the 192 Athenian dead following the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE still exists at the plain’s centre. The mound has been investigated by archaeologists and it was confirmed that the cremated remains of the Greeks are still within the tumulus. Photo © Ben Churcher

From the island of Salamis the Athenians could only watch as they saw the smoke from their beloved city curling into the sky: but they would have their day. Now on the outskirts of Athens and amid oil refineries and other industry, the narrow stretch of water between Salamis and the mainland was soon to witness a remarkable victory by the combined Greek navy over the Persians.

Now with the Greeks as masters of the sea, the Persian invasion force was vulnerable as it meant that the Greeks could sail to the Hellespont, break apart the Persian bridges and trap the Persian army in Greece. Realising this, Xerxes hightailed it for home leaving the bulk of his army to winter in the north of Greece.

Xerxes Canal, Athos Peninsula. This view shows the western-most end of Xerxes’ canal which created the cutting seen here (with the first telegraph pole in the centre): the channel of the canal has almost completely filled in now supports swampy vegetation such as the reeds seen here. Photo © Ben Churcher

The following year, in 479 BCE, the Persians advanced south and were met by the combined Greek army in front of the city of Plataea: the citizens of which, you may remember, were the only allies to fight with the Athenians at Marathon.

At this unvisited spot to the northwest of Athens, later-period towers and walls can still be seen overlooking a broad valley where the main engagement took place. It was a spread out affair and again it was Spartan military might that carried the day when their forces captured the Persian camp and brought about the defeat of the Persian army.

This action ended the third and most serious invasion by the Persians who never again ventured to dream of conquering the Greeks. Following the Battle of Plataea, Herodotus recounts that the leader of the Greeks, Pausanias, amazed at the sumptuous splendour he found in the Persian camp, asked the Persian cooks to prepare a typical meal that they would have once prepared for the Persian commander Mardonius. As a joke he then asks the Spartan cooks to prepare their usual meal and when the two were ready he calls in the other Greek commanders and shows them the staggering difference between the spreads. As they marvel at the Persian brocades, silks and golden plates, Pausanias says to them, “Gentleman, I have called you here to see the folly of the Persians, who, living in this manner, came to Greece to rob us of our poverty”.

Acropolis Museum. The recently opened Acropolis Museum has been purpose built to pay homage to the nearby Acropolis and its crowning treasure, the Parthenon. The museum houses the Parthenon Marbles, as well as statues and other votive offerings that have been unearthed on the Acropolis. Photo © Ben Churcher

This bonhomie among the Greeks was not to last and within a generation they would be at each other’s throats in a war that was to sap the vitality of ancient Greece and allow a new kid on the block to emerge: Macedon. But for the moment Greece was safe and the undisputed master of the eastern Mediterranean. The Classical Period flowered during this time and we, even today, live with the legacy of these years every time we cast a vote, visit a theatre or ask ourselves “am I happy?”

Naturally there is much, much more to visit in Greece but to walk in the footsteps of Xerxes and his predecessors, Herodotus in hand, is a chance to relive a time when the small, fractious and bellicose cities of Greece withstood a force so powerful that its effects still reverberate today.

About the Author

Ben Churcher has a wide range of experience both as an educator, a traveller, a historian and an archaeologist. He holds an Honours degree in Ancient History, is Field Director at the University of Sydney’s excavations at Pella in Jordan and regularly gives public lectures on archaeological subjects for adults and students. Ben is Director of Astarte Resources, a company that produces and distributes educational material specialising in ancient history and archaeology and for the past 20 years Ben has led numerous tours throughout the Middle East, North and West Africa, Greece, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, China and Mexico. Ben lives in Queanbeyan, Australia.