While I was photographing two large blocks at the main hall of the Sulaymaniyah Museum, I read that these blocks were part of the Sassanian tower of Paikuli. “Paikuli”(Arabic: بيكولي; Kurdish: په يكولي): a new name to me! I went home and surfed the net trying to find out what this tower represents. After getting the information, I phoned Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah, the director of the museum. “Please, guide me on how to get there,” I asked him. He replied positively.

It was a very sunny and hot day in mid-summer, and it was a holiday. I took a relative of mine, who resides near Lake Darbandikhan (Arabic: دربندخان; Kurdish ده ربنديخان), about 80 km south to the city of Sulaymaniyah. We drove south through Bani Khellan (Arabic: باني خيلان; Kurdish: باني خيلان) and then turned west to the foot of Paikuli pass to reach Barkal village (latitude 35° 5’53.91″N; longitude 45°35’25.95″E). The latter lies very near to the ruins of the Paikuli Tower. The ruins can be seen on a hill at the right side of our road.

I used my car to ascend to the top of the hill through a narrow path. A mountainous range looks over the hill. At last, here it is!

Panorama view of the ruins of the Paikuli Tower. This is the base of the tower and is surrounded by stone blocks. The blocks have been rearranged in situ by the Italian archaeological team. The tower was built on the top of this hill, and there were no foundations beneath the earth, as the Italian team concluded. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Let the time machine take us back. In the year 293 CE, Narseh (also written Narses), brother of the Sassanian king Warham II (also written Barham II) and son of King Shapur I, was in Armenia, very far away from the Sassanian capital of Ctesiphon. In the same year, Warham II died and his son, Warham III, succeeded him and reigned only for few months. Several nobles and notables considered Warham III too weak to rule the Sassanian Empire and supported his grand-uncle, Narseh, in ascending the throne.

Narseh marched back and revolted against Warham III and finally killed his nephew. Narseh then became the seventh Sassanian king.

On the top of this hill, about 1,700 years ago, those Iranian nobles and notables were waiting for the arrival of Narseh (from Armenia) to swear their loyalty and confirm their support. In commemoration of this turbulent time, Narseh built a square-shaped tower on this place (this hilltop), which was part of the border of Asorestan. Narseh documented the event on two sides of the tower, using the Parthian language on one side and the middle Persian language on the other. The two versions of the inscriptions were almost identical. The inscription generally narrates what had happened in two parts; the first part was the circumstances of the war and ascent to power, while the second mentions the names of the nobles and notables who backed up Narseh.

The western wall inscription was written in middle Persian and consisted of 46 lines and eight horizontal stone blocks. The inscription on the eastern side was the Parthian version and composed of seven horizontal stone blocks forming 42 lines of inscription. These inscribed stone blocks are now in the Sulaymaniyah Museum; the field only contains the stones that were used in the construction of the tower.

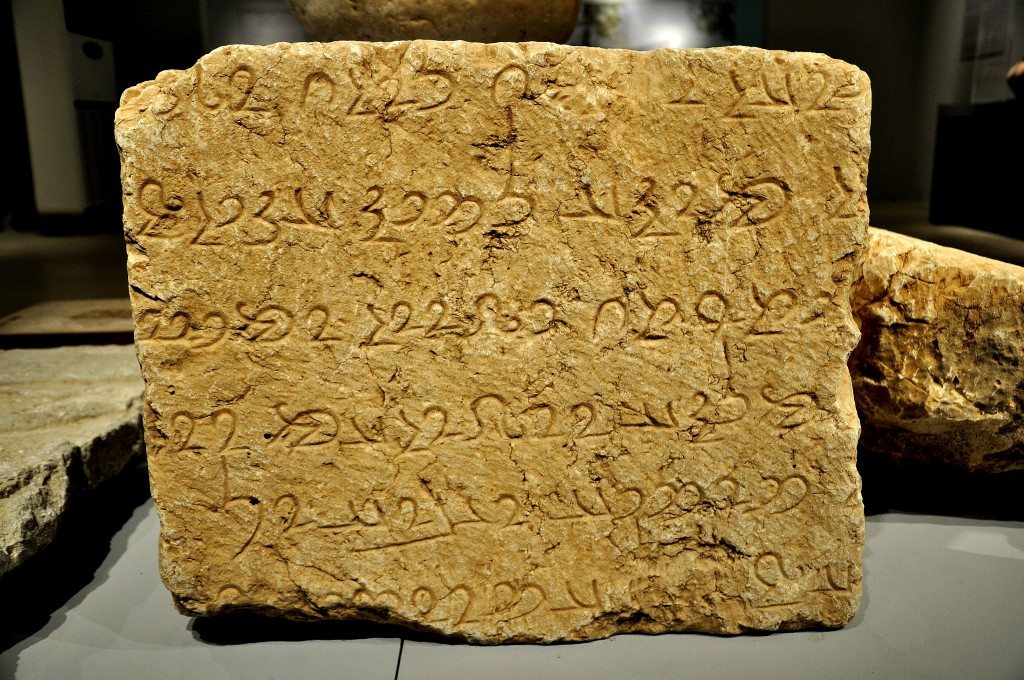

One of the two inscribed blocks on display in the Sulaymaniyah Museum. The middle Persian language was used on this stone block. (Block No. PK 22; on tower No. D3 ; 56.51 x 48 x 26 cm; SM2696; acquisition year 1997). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Several archaeologists visited the site and published many articles about it. The British consul, Henry Rawlinson, visited the ruins in 1844 CE and made drawings of 32 blocks (and later published them). The German archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld extensively studied the ruins and documented the inscriptions from 1911-1913 CE. Thereafter, several scholars started their work on the inscriptions. Humbach-Skjaervø extensively published on this subject during the past century. According to Humbach-Skjaervø, the total number of the blocks is 230-240 and the total length of the text is 940 cm; this makes it the longest surviving Sassanian inscription found to date.

An Italian archaeological team has been working on the ruins since 2006 in collaboration with the Sulaymaniyah Museum and the Sulaymaniyah Antiquities Directorate as part of the “Paikuli project in the Kurdish region of Iraq”, which was funded by the “Task Force Iraq” of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[embedyt]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYHjJ7ohmxY[/embedyt]

Surprisingly, the ruins have not undergone any organized looting during the past centuries. During the Iraq-Iran war era (1980-1988 CE), in spite of the extensive military operations there, the ruins were relatively untouched! During the late 1990s, the Sulaymaniyah Museum transferred all of the inscribed blocks in addition to four busts of Narseh from the site to the museum to protect them.

Recently, in 2014, Carlo Cereti and Gianfilippo Terribili of Sapienza University of Rome published an article about the discovery of a new inscribed block. They have identified 19 new blocks (eleven middle Persian and eight Parthian). They are part of the Italian team mentioned above.

Some of the inscribed blocks are still missing, and the entire text is incomplete to date. Some blocks might well have been used by local villagers for their personal use on their farms. Others might have been completely damaged and eroded. A few might have been “looted” or destroyed during the military operations in the 1980s.

This is the western wall, where the middle Persian version of the inscriptions was present. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The base of the tower is still there, and the blocks are scattered all around the monument. I sat there, took pictures, shot a video, and had a shish kabab lunch! I asked myself: Who designed the monument, how many workers participated in the construction process, who cut and transferred these very heavy blocks, who wrote the inscriptions, and who witnessed the death of Warham III?

I’m not an archaeologist! Iraq is not an easily accessible country for many. I’ve concluded that this Sassanian tower is very important to historians, anthropologists, and archaeologists. I hope I have been helpful in conveying this scent of history to you! I’m very thankful to Mr. Hashim Hama Abdullah (Director of the Sulaymaniyah Museum), Mr. Kamal Rashid (Director of the Sulaymaniyah Antiquities Directorate), Mr. Akam Omar (sculptor at the Sulaymaniyah Museum), and Ms. Awaz Jihad (archaeologist at the Sulaymaniyah Museum) for their extreme help and cooperation!

More Photos of the Paikuli Tower

Shooting from the top of the tower’s ruins. Barkal village and the Paikuli pass can be seen in this panorama view. Note the scattered stone blocks which were used for building the tower. These block have no inscriptions. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Parthian version of the inscriptions was present on this eastern wall. Note the scattered stone blocks and their fragments. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The southern wall has collapsed totally and its ruins and stone fragments have merged with the hill’s surface. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

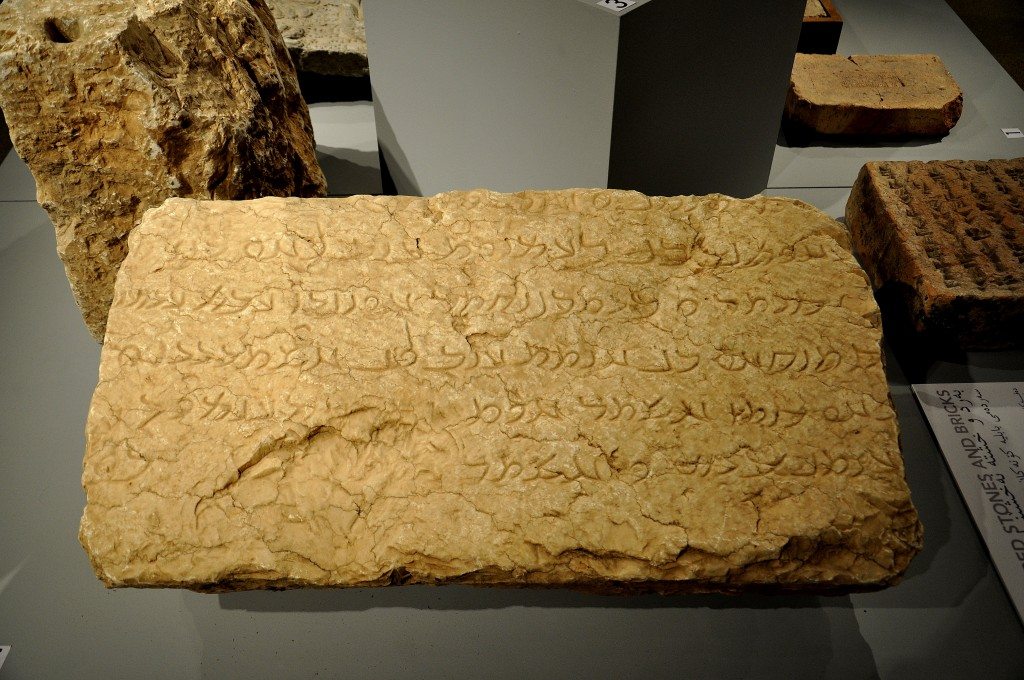

Another inscribed stone block in the Sulaymaniyah Museum. I intentionally did not crop the image. Note the thickness of the other inscribed stone block (left of the viewer) and the size of this block, on which the Parthian language can be seen. (block No. PK97; on tower No. F7; 87 x 48 x 19 cm; SM2771; year of acquisition 1997). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

These are two (out of five) busts of King Narseh, which decorated the Paikuli Tower. The Sulaymaniyah Museum. Exclusive photo! Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.