August 11, 2014. It was a partly cloudy day. I arrived at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin around 10 AM. I found a long queue . . . Average waiting time: two hours! I asked a guard about this. He said, ”This line is for holders of priority pass tickets and pre-booked tickets.” I said, “OK, where I can buy this priority pass ticket?” The answer was, “You have to join this long queue, and once you enter into the museum’s main reception, you can buy this type of ticket.” The ticket costs 24 Euros; it is valid for three consecutive days, and you can use it to enter the other museums at “the Museum Island in Berlin” and other museums within the city of Berlin. It’s an excellent deal!

Finally, I went upstairs and found myself within the Processional Way of ancient Babylon. What a feeling I had! The Ishtar Gate faces the Processional Way. I walked back and forth, through the gate and the street, maybe ten times. I said to myself, “Nebuchadnezzar and his army walked through this gate!”

Pergamon Museum Courtyard. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Mesopotamian section dominates the Pergamon Museum and is divided into several halls and collections on either side of the Processional Way. In general, each room displays artifacts from a specific and remarkable period in Mesopotamian history.

It was approaching 5 PM. I was very exhausted and hungry! For about ten minutes, I went quickly to see the Pergamon Altar and Market Gate of Miletus. I did not visit the collection of Islamic art.

A few points to note:

- The Museum and its sister museums on the Museum Island are undergoing renovation works. Many artifacts and their display cases were removed in order to protect them. The Pergamon Altar is closed to the public until 2019, as are the museum shop and café. The Mesopotamian collection remains unaffected by the construction work.

- The number of seats on site was relatively small. There was a wide range of visitors; some cannot stand/walk for a long time. In addition, and because of the re-construction plan, the lift was out of use and wheelchair access was limited.

- The majority of descriptions are only in German.

Altogether, it was a great experience. The scent of history is thrilling!

Babylonian Glazed Brick

A close-up view of some glazed-bricks which decorate either side of the Processional Way of Babylon. Neo-Babylonian period, 575 BCE. From ancient Babylon, modern Bebel Governorate, Iraq.

Glazed Brick. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Ishtar Gate

The Ishtar Gate of Babylon. It was made of glazed-bricks and was decorated with bas-relief aurochs and sirrushs. A wall plaque from the throne room of King Nebuchadnezzar II also appears on the left. Neo-Babylonian period, 575 BCE. From ancient Babylon, modern Bebel Governorate, Iraq.

Ishtar Gate. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Inscription Plaque of the Ishtar Gate

In this photo, part of the so-called inscription plaque (or building inscription) of the Ishtar Gate appears. The cuneiform inscriptions of the whole text read:

“I (Nebuchadnezzar) laid the foundation of the gates down to the ground water level and had them built out of pure blue stone. Upon the walls in the inner room of the gate are bulls and dragons and thus I magnificently adorned them with luxurious splendour for all mankind to behold in awe.”

These glazed bricks were found near the main Ishtar Gate during the German excavations of the area, 1902-1914 CE. Neo-Babylonian period, 575 BCE. From ancient Babylon, modern Bebel Governorate, Iraq.

Inscription Plaque. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

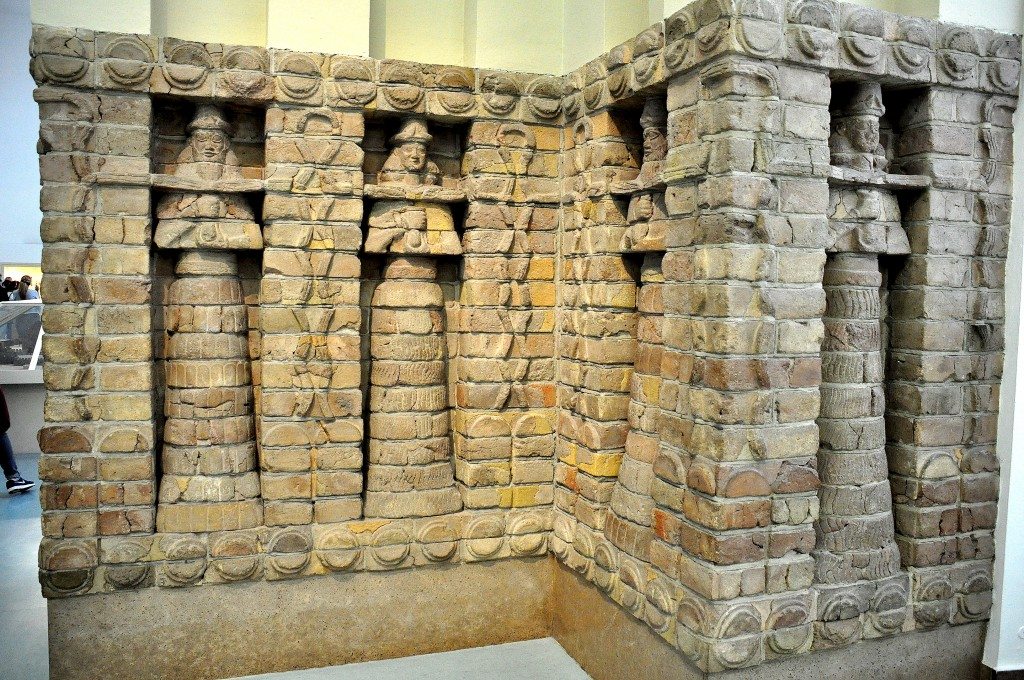

Temple of Inanna Facade

This is part of the facade of the Temple of Inanna at Uruk. There are standing male and female deities in alternate niches. Each figure holds a vessel in his/her hands and pours life-giving water forth onto the earth. The cuneiform inscriptions on the bricks mention the name of the Kassite ruler Kara-indash as the person who ordered the building of this temple. C. 1413 BCE. From Uruk, southern Mesopotamia, Iraq.

Temple Facade. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Statues from Ashur

Within a hall which displays various artifacts from the Assyrian Empire. On the left, there is an alabaster statue which depicts a man who wears a fringed robe. It probably came from an Ishtar temple. The statue likely represents a local ruler of the city of Ashur; his name was Zariqum. This ruler was loyal to Amar-Sin, king of Ur. The man’s garment and his posture are consistent with similar artworks of that period. Ur III, c. 2000 BCE. From Ashur, northern Mesopotamia, Iraq.

In the middle is a black statue. This statue was unearthed during the German excavations at the city of Ashur in 1905 CE. The statue depicts a man in a long gown, which is girded at the waist with a belt. The details of the body, especially at the shoulders and upper arms are marvelous. In the year 1983 CE, Iraqi archaeologists discovered the head of this statue at the same place. Altogether, the hairstyle of the man, his dress, and the artistic treatment of the body are consistent with sculptural art during the reign of Manistushu of Akkad. Therefore, this man could be a local Akkadian rule of the city of Ashur. From Ashur, northern Mesopotamia, Iraq. C. 2300 BCE.

On the right, there is an alabaster bas relief from the north-west palace of King Ashurasirpal II at ancient Kalhu (modern Numrud), 883-859 BCE. Northen Mesopotamia, Iraq.

Assyrian Statues. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Standard Inscription of Ashurnasirpal II

A close-up view of the “standard inscription of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II.” A hand of an Apkallu (sage) appears on the right. This inscription narrates the king’s title and achievements and is repeated on almost all wall reliefs at the North-West palace. Neo-Assyrian era, 865-860 BCE. From the North-West palace at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu; biblical Calah), northern Mesopotamia, Iraq.

Standard Inscription of Ashurnasirpal II. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Bearded Alabaster Man

This is the upper part of a small alabaster (height 46 cm) statuette which depicts a bearded, bald-headed man. He clasps his hands in prayer. The upper part of the body is naked, while the lower half is covered by a sheepskin skirt. It was found in the anteroom to the cella of the archaic Ishtar Temple in the city of Ashur. The statuette most likely represents a priest/man of a high rank. From Ashur, northern Mesopotamia, Iraq. Early dynastic period, c. 2400 BCE.

Bearded Man. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

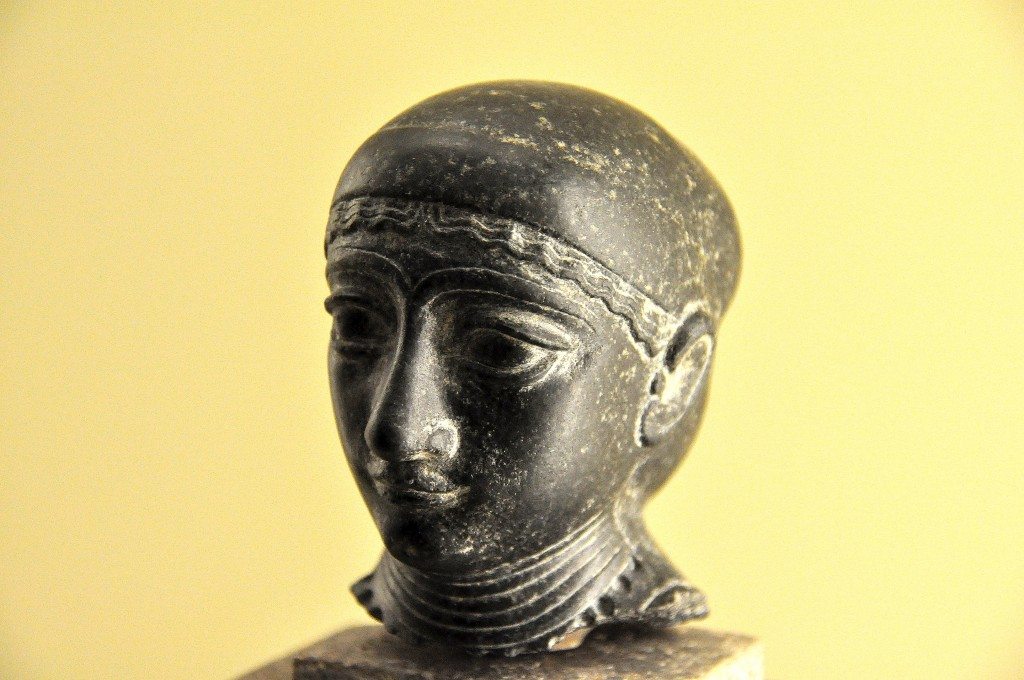

Head of a Woman

A diorite head of a woman. The rest of the statute is missing. There are no cuneiform inscriptions telling us who this woman is. It was found at Tell Telloh, ancient Girsu, southern Mesopotamia, Iraq. 2144-2124 BCE.

Woman. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.