Today we have another contribution from Timeless Travels Magazine in which Annabel Venn writes about her visit to the Angkor Archaeological Park.

Angkor is one of the most famous archaeological sites in Asia. Filled with fellow travellers, it can be overwhelming at times. Annabel Venn gives her advice on how to beat the crowds and experience this fabulous site in peace

The small light flickers on the front of my bicycle, barely illuminating the dark road ahead. A minibus full of snoozing passengers passes me, rather too close for comfort, offering me a brief glimpse of where I am pedalling. With a free hand, I wrap my Cambodian krama up around my neck; it is already warm but the cool breeze is chilling at this time of the morning. Not often am I persuaded to get up before the sun does, but today I am guided by a sense of exploration. Ahead of me lies the ancient city of Angkor.

The site of Angkor

Angkor Archaeological Park is vast, overwhelming perhaps. Four hundred square kilometres of crumbling temples scattered amidst thick jungle, and at the heart of it lays Angkor Wat, a sight that epitomises South East Asia. Situated 6 km to the south is Siem Reap, once no more than a small village, now described as the gateway to Angkor. Falling to the hands of the Khmer Rouge during the Cambodian genocide, it has rebuilt itself into a hugely popular tourist destination, of which the temples of Angkor are undeniably the main draw. Planning a visit generally relies on two factors; time and budget. Many recommend a minimum of three days, allowing time to take in the temples further afield, and it would certainly be easy to plan a week-long itinerary. Tickets to the site are available as a one-day, three-day or one-week long pass. A one-day ticket gives you access to the site from 5 pm on the previous evening, making it feasible to hire transport for the evening and watch the sun going down – a welcome introduction to the majesty of Angkor.

This article was originally published in Timeless Travels magazine. Republished with permission.

Getting around is simple; you only need to spend a short time in Siem Reap to realise the plethora of transport options available, ranging from the comfortable seats of a private car to atop the noble elephant. For independent travellers the remork-moto (often called a tuk tuk in neighbouring countries) is a popular option. Negotiate with one of the many drivers

you will find in Siem Reap (although it is likely they will find you first!) – most follow a set route but it can be adapted to

suit a personal itinerary. While most speak a good level of English, hiring a guide or purchasing a comprehensive guidebook can be fundamental to the enjoyment and understanding of a visit around a site with relatively little information. I found a second-hand copy of acclaimed Ancient Angkor by Michael Freeman which became my font

of knowledge.

For me, transport was a simple choice – a bicycle. Being a regular cyclist at home, I was confident I could cope with a

long day in the saddle. However, as I handed over the princely sum of $2 for a whole day’s rent, I was immediately reminded that rather than my beloved road bike, I was being paired with the humble Asian bicycle. Still, at least its features were memorable; a saddle that produced a noise not too dissimilar to a honking goose every time I shifted my weight, wonky handlebars that required me to steer slightly to the left in order to remain heading in a straight line, and brakes that demanded every ounce of my strength in order to be remotely effective. I had also overlooked the heat of the Cambodian sun. At night it was warm; when the sun came up it was hot; by mid-morning it was stifling; by midday, positively unbearable. At the very least it encouraged some faster pedalling to benefit from the breeze!

Alternate route

As someone who is keen to stay off the main tourists trails, I was somewhat apprehensive about visiting a site which boasts over 2 million visitors a year. It is not uncommon to see queues of tourists waiting to have their photo taken in front of a particular doorway or viewpoint. Not unsurprisingly, Angkor Wat is one of the most popular places to view the sunrise, the warm glow of the sun rising up from behind the impressive towers. The experience is breath-taking, but you will need to be prepared to share the moment with hundreds, if not thousands, of chattering tourists, firing camera shutters and ‘selfie sticks’ raised high above heads. Without difficulty I made the decision to find my own space for sunrise, choosing instead to visit Angkor Wat late in the afternoon.

I left Siem Reap at around 4.20 am, stopping en route to purchase my entry pass. By the time I reached Angkor Wat around 45 minutes later, the hoards arriving in motorised transport had already arrived. Tour groups piled out of their air-conditioned coaches, clutching an array of bottles, cameras and umbrellas. I passed the entrance and turned left, positive that I would not regret missing out on their experience.

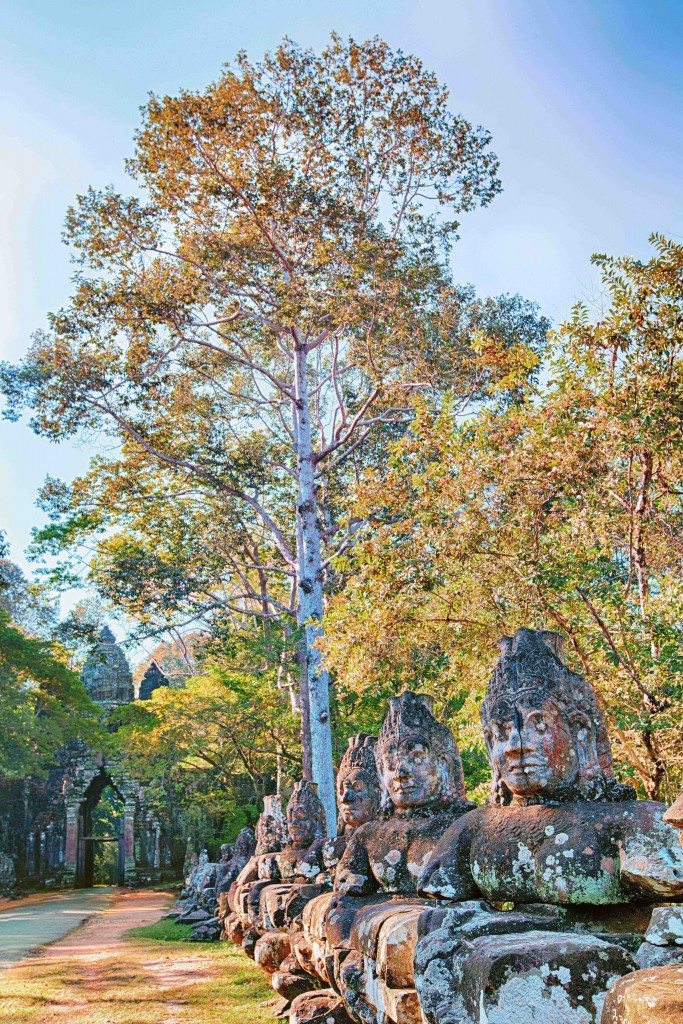

The road felt almost completely deserted as I passed under the south gate of the Angkor Thom complex, dull shadows of the stone carvings cast on the path. Arriving at the huge structure of Prasat Bayon, its many towers jutting into the sky, hushed muttered voices were within earshot. There were a handful of remork-motos, and only a few other bicycles were visible as I chained mine against a nearby tree. Glancing up, it was possible to make out a few of the huge faces which have become so distinctive of Bayon’s features. I climbed the first few steps and entered a dark corridor, flicking on my head torch only briefly to settle my footing. Emerging onto a rocky plateau, I sat for a while, waiting. The towers overshadowed everywhere I looked, and as the sun broke through the trees, stony smiles lit up across the iconic faces. According to a few sources, the exact owner of these faces remains debatable; either the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara or Bayon’s creator, King Jayavarman II. They watched me as I explored the eerie tunnels and dark passageways, pausing to decipher the intricate carvings of seemingly everyday life – fish-sellers at a market, a woman giving birth and men preparing their elephants for battle.

Leaving Angkor Thom behind me, I pedalled through the Victory Gate and headed eastwards. The road was quiet, not deserted, but quiet enough that I could begin to savour the reality of where I was. I stopped momentarily at a few lesser-known temples en route, including Chau Say Tevoda and Thommanon, before reaching Ta Keo. Noted for possibly being the first temple made solely of sandstone, its green hue stands unique among the browny-grey colour of others. The state temple of Jayavarman V, who was only 17 when it was constructed, is said to have never been completed as it was struck by lightning, an evil omen. Some architects believe this to be the reason why there are no external carvings; others suggest the hard sandstone was too difficult to carve. Sadly much of it was closed for restoration, so I continued on for one kilometre, arriving at the west gate of the picturesque Ta Prohm temple at around 8.30 am.

Originally called Rajavihara, work started on Ta Prohm in 1186 and is one of only a few temples with an inscription detailing its origins, found on a stone stele discovered within the temple. Once home to 12,640 people, Ta Prohm has been left predominantly to the mercy of Nature. Ancient strangler figs climb the stone temple walls, twisting and winding their way towards the jungle canopy. ‘There is a poetic cycle to this venerable ruin,’ my guidebook reads, ‘with humanity first conquering nature to rapidly create, and nature once again conquering humanity to slowly destroy.’ Iconic photos of erratic tree roots are used on numerous brochures, and it is clear to see why. As I entered, a nun was arranging sticks of incense into a pot of sand, the intense smell wafting through the doorways. I politely declined as she thrust one in my direction, not wishing to part with a fistful of dollars in return. Having entered from the west gate, by mid-morning I soon found myself struggling against the natural flow of tour groups. A wooden path runs roughly through the middle – an attempt to cope with rising visitor numbers – but leaving this path and exploring the outer edges of the site offers some relative solitude. Known as the ‘Tomb Raider Temple,’ I had a very personal reason for visiting, as my godfather was one of the location managers for the film franchise. However, I could not help but wonder if the success of the film had been directly responsible for an increase in tourism, and the questionable negative impact this could have created for the temples.

Pedalling on to the Buddhist monastery Banteay Kdei, I was welcomed by the uniformed guard as he checked my entry pass. He asked me if this was my first visit to Angkor and gave me a brief history of the temple, having worked there for three years. As I explored, once more I was watched by similar smiles to those of the Bayon temple. Crossing the road, a gentle walk around the waters of the royal bathing pond Srah Srang offered me complete peace from anyone else. Most tour groups return to Siem Reap for lunch, so if you can stand the heat of the midday sun, it is a good time to explore the popular temples. Forfeiting my usual packed lunch, I succumbed to another opportunity to have my favourite Cambodian dish, lok lak – a rich beef dish with a lime and pepper sauce, usually accompanied with a salad. There are plenty of places to eat around the site, albeit with inflated prices; I propped up a plastic chair in the shade of a stall on the roadside.

Following the loops

All morning I had been following a route known as the ‘Small Circuit,’ a 17 km loop taking in the most admired of the Angkor temples. It is usually advisable to stick to this loop, saving the Big Circuit for another day, but after lunch I backtracked to join the bigger loop going in the opposite direction, as I was limited by time. Afternoon stops were brief but varied – admiring the view of surrounding rice fields atop Pre Rup; gazing in awe at the huge, well-preserved stone elephants guarding East Mebon temple; resisting every urge to jump from the boardwalk into the crystal clear waters of Preah Neak Poan. Continuing west the road presents Preah Khan, renowned as a fusion of dedications to Buddha, Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu. Comparatively empty due to its location, the site is a maze of long corridors, lined with intricate carvings and guarded by nagas, serpent deities. A two-tiered independent structure is striking and unique among all other temples – not only showcasing the endurance of Khmer masonry, but also providing a useful reference point for orientation of the huge area.

Entering Angkor Thom once again, through the north gate, I paused for a fresh coconut on the roadside. As the lady wielded a machete to hack the top off, I was struck once again by the grandeur of the ruins around me, the last great capital of the Khmer empire. I spent a short time looking at the temples I had only seen shadows of in the early morning, not doing them justice with exploration, but not wanting to fill up the remaining daylight hours with too much. Departing through the south gate, the spindly trees lined along the bank of the river were perfectly reflected in the still waters. I paused to watch some children playing with a troop of monkeys by the side of the road, shrieks of laughter erupting as one gibbon hopped onto my bike saddle and perched there, eating a banana.

My penultimate stop was at the mountain temple of Phnom Bakheng, undoubtedly the most popular sunset viewpoint. A 20 minute climb up the hill offers a spectacular panoramic view over Angkor. I visited at around 3.30 pm, finding it completely deserted except for a pair of elderly Chinese ladies who were struggling with the climb in the oppressive heat. They laughed as I offered my hand to help pull them up. A flight of exceptionally steep stairs stood between me and the top, and I was grateful I had listened to the advice to wear a pair of sturdy shoes. Looking out over the Western Baray, I found myself completely alone, not for the first time that day. It felt miles away from the noisy motors and incessant chatter of Siem Reap. In the distance I could see the rising towers of Angkor Wat, my final destination.

Angkor Wat at last

‘Relish the very first approach, as that spine-tickling moment when you emerge on the inner causeway will rarely be felt again,’ my guidebook stated. I was hesitant. Too often I had met other travellers who had been underwhelmed by the iconic view they had seen so many photos of. I was immediately struck by the symmetry, unlike many of the other temples where it is hard to see the sum of all its parts at once, but there in front of me was Angkor Wat – the largest religious monument in the World, standing majestic and proud against a backdrop of vivid blue sky. Perhaps I had saved the best until last, but my initial sight of Angkor Wat was simply breath-taking.

Declared by UNESCO as a World Heritage site in 1992, the Khmer people are fiercely proud of Angkor Wat; the temple was added to the national flag in 1863 and is one of only two countries currently to feature a national monument (Afghanistan being the other). Covering a 500 acre site, Angkor Wat was designed by King Suryavarman II and built between 1113 and 1150. Hindu mythology claims that the Gods lived on Mount Meru, its five peaks surrounded by ocean. Angkor Wat is said to be a direct reflection of this; each of the five towers shaped like unopened lotus blossoms, the whole temple surrounded by a moat.

Perhaps the temple’s most unusual feature is that it was built facing west, a direction usually associated with death in Hindu culture. This has led some archaeologists to believe that the temple was built as a mausoleum to honour its creator. Further evidence is found in the bas-reliefs which are read counter clockwise. Yet despite the suggestion of links to death and funeral rituals, beauty is abundant in the 3000 carvings of attractive apsaras, each unique. Stood at the foot of Bakan, the upper level chamber, it is unimaginable that somebody could not to be impressed by the workmanship, an original representation of the classical style of Khmer architecture. ‘Khmer bricks were bound together not using mortar, but by a vegetable compound. Over five million tons of sandstone had to be quarried from a site 25 miles away from here,’ I overheard a guide explain to his group, ‘it was floated down the river on planks of wood.’

Looking around me it is difficult to conceive. Inscriptions have implied around 300,000 workers and 6000 elephants were involved in the construction. With the sun melting into the distance, I joined a growing crowd at the northern pool to watch the Angkor Wat disappear into darkness for another day.

Excursion to Beng Melea

That evening an unexpected meeting with a talkative remork-moto driver named Kou left me questioning my personal footprint as a tourist in the town of Siem Reap. After speaking with him a while, I asked him what he felt the impact had been on Siem Reap as a result of the increasing tourism. ‘I think it is good and bad,’ he replied, ‘it is bad when I see groups on big buses as they do not experience the sights or sounds or smells. But it gives me work, and I want to help people see my Cambodia and not the tourist Cambodia.’ I needed very little persuasion to accept when he offered to drive me out to Beng Melea the following day, promising to take the long way round and show me his country. ‘You pay me what you want,’ he said.

Beng Melea is located 77 km from Siem Reap by road, resulting in fewer visitors making the hour-long car journey to see it. The two-hour drive in a remork-moto was spectacular. We bumped along burnt-orange roads, a stark contrast to the surrounding vivid green pastures. Farmers worked in the fields, fisherman standing waist deep in a murky river waved as we passed, motioning for me to join them in the water with beaming smiles across their faces. Children and dogs ran alongside us, animated shouts of ‘Hello! Hello! Hello!’ By the time we reached the main road to Beng Melea I was well and truly shaken up, but Kou had been true to his word and shown me that sometimes the long way is the most memorable. The first glimpse of Beng Melea is impressive, a tangle of roots and branches strangling the bricks beneath. The initial entry point is a steep metal staircase up to the first level. At the top an Apsara caretaker spotted my camera and pointed towards a crumbling doorway in the ruins, seemingly impossible to access. ‘Photos, go there’ he exclaimed in stilted English. He pointed a weathered finger towards some makeshift stone steps, motioning the way. ‘Aw kohn,’ I replied, struggling over the maze of moss-covered bricks. As two temples that have been overrun by nature, it is easy to compare Ta Prohm to Beng Melea. However if the former was a parent, guiding her visitors over a wooden walkway towards a safe passage, then Beng Melea would be the grandparent, spoiling you with paths and nooks to explore, with no real guidance or care for safety. Ta Prohm has been manicured; Beng Melea is rough and raw. I could not but help feel a certain sense of guilt as I scrambled over broken rocks and through lichen-covered doorways. Bending to avoid a low-hanging vine, I managed to rip my

trousers, laughing to myself as I negotiated the bricks like a rock-climber, vegetation running amok everywhere around me.

Created by the same King Suryavarman II responsible for Angkor Wat, it is hard to imagine how Beng Melea could ever have been similar to its better-known cousin. For a sense of what it might have been like to be one of the French explorers discovering Angkor, Beng Melea might be the closest thing; it is not something to see, it is something to do – the ultimate definition of a ‘lost temple.’

On the drive back to Siem Reap, Kou asked me what I had learned from my visit to Angkor. My answer was simple – not enough. Being on a bicycle had allowed me to take the occasional remote dirt track or short-cut, but I had left with so much undiscovered and unlearned. I made a promise to Kou, and to myself, that this was not going to be my only visit to the temples of Angkor.

About the Author

Annabel has worked in the charity sector for 4 years, supporting fundraisers taking part in challenge events both in the UK and abroad. Inspired and encouraged to travel by her Nana, she prefers to find the road less travelled. Previous adventures have taken her eagle hunting with Mongolian herders in the Gobi desert, working as a jillaroo in the Outback, taking part in a tea-drinking competition in Mandalay and hitching a lift up a Colombian volcano in a milk float. Most recently she spent 3 months teaching English at a horse ranch on the southern coast of Cambodia.