Sixth graders typically have some background knowledge of Egypt, Greece, Rome and the Maya when we begin studying those civilizations. Right now, we are near the end of the Mesopotamia unit, about which they typically know little coming in. It has been nice to spend three weeks with every day being a brand new topic for my students. I introduced the concept of a civilization and talked about the seven characteristics according to our textbook–social structure, government, stable food supply, religion, the arts, technology, and writing – before we delved into a project that combined these characteristics: making cuneiform tablets.

The most challenging concept for sixth graders to wrap their minds around is the importance of farming, many aspects of which were kept track of on cuneiform tablets. Coming from an urban environment, where most food comes from a store, the stages of food production prior to store arrival are lost and rarely contemplated. We ran a couple scenarios showing the extreme difficulty of hunter/gatherer tribes, and they truly appreciated the hardships and daily struggle for survival of prehistoric peoples. The archaeological discoveries at Jarmo indicating the early stages of a farming culture? No big deal. If there was one takeaway I hope they grasp from this unit, it would be the importance of farming; but even on year five of teaching, I can’t quite connect the dots for them.

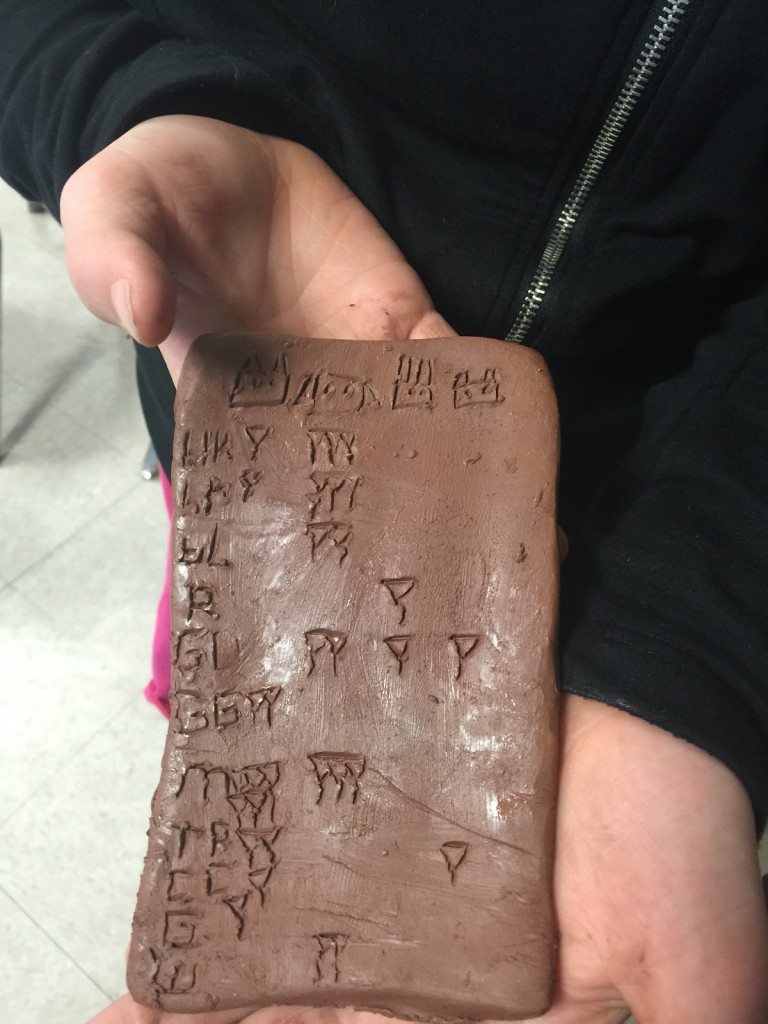

Before making the tablets, we spent a day learning the basics of the ancient Sumerian number system, made inferences from tablet translations, and learned that Mesopotamians typically used writing to keep track of important goods, land, and people. After that, we began making our tablets. Students got to show off their skills with a stylus (cuticle pusher) on red clay using cuneiform (Sumerian wedge-shaped writing). They chose what they will keep track of on their tablets and asked their classmates, friends, and families to fill up their charts. Since items sixth graders typically choose generally didn’t exist in ancient Mesopotamia, we stretch it a little and have them evolve pictographs into their own phonograms, just like the writings from 5,000 BCE-1,500 BCE in the Fertile Crescent. I try to act like a Mesopotamian scribe teacher, minus the excessive beatings, with harsh remarks and constant re-dos of their clay tablets of Sumerian numbers mixed with their cuneiform. We always talk about my scribe role at the end of the class and, as you can imagine, leave 10-20 minutes for clean up.

Is this a groundbreaking and innovative strategy for teaching ancient Mesopotamia to sixth graders? Maybe not, but getting hands-on with history makes for some of the most entertaining days of our 180 day trek.