When you enter Room 7 of the British Museum, after passing through two colossal lamassus, you are taken through time to the North-West Palace of the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE). This is the imperial palace of the King in Nimrud (ancient Kalhu or Biblical Calah; Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq), the capital city at the heart of the Assyrian Empire. Room 7 is a long hall “decorated” with alabaster-bas wall reliefs from that palace. After being neglected for more than 2500 years, British archaeologist Sir Henry Layard and his workmen unearthed the remains of the North-West Palace in 1845. Layard shipped many reliefs on the Apprentice and these large and heavy slabs reached the British Museum in January 1849. I will publish a series of articles about these reliefs, addressing their finer details, which are not easily recognised.

Room 7: Wall reliefs from the North-West Palace at Nimrud. Grand Floor, The British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

During the Neo-Assyrian period (911-612 BCE) Apkallus were supernatural creatures (or demigods) who were richly depicted in palace reliefs. Apkallu, sage, or genie are interchangeable terms used by Assyriologists to describe human-headed (male or female) or eagle-headed and winged (with 1 or 2 pairs of wings) figures. Sometimes they wore a fish-skin cloak. The figures are actually protective spirits or guardians (just like angels), who protect the king (as well as the palace and its inhabitants and contents) against evil spirits. The majority were placed flanking room entrances or corners (this is where the evil spirits were thought to reside).

Near the entrance to Room 7, there are two large 2-meter high alabaster bas-reliefs of standing male creatures, each one holding an animal. But, what is unique about these reliefs?They came from two different rooms within the North-West Palace though they share many similarities they are unique from each other and the other Apkallus in the same palace. Although wall reliefs and panels from the North-West Palace can be found in many museums around the World, only the British Museum houses such a unique theme of “phenotypically” different Apkallu holding a goat or deer.

Two alabaster bas-reliefs from the North-West Palace of the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud. The panels show two standing Apkallus (human-headed and winged protective spirits), one holds a goat (right) and the other holds a deer (left). The figures face the door’s entrance. Two Lamassus also appear at the other side of the room’s entrance. From Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Genie and the Goat

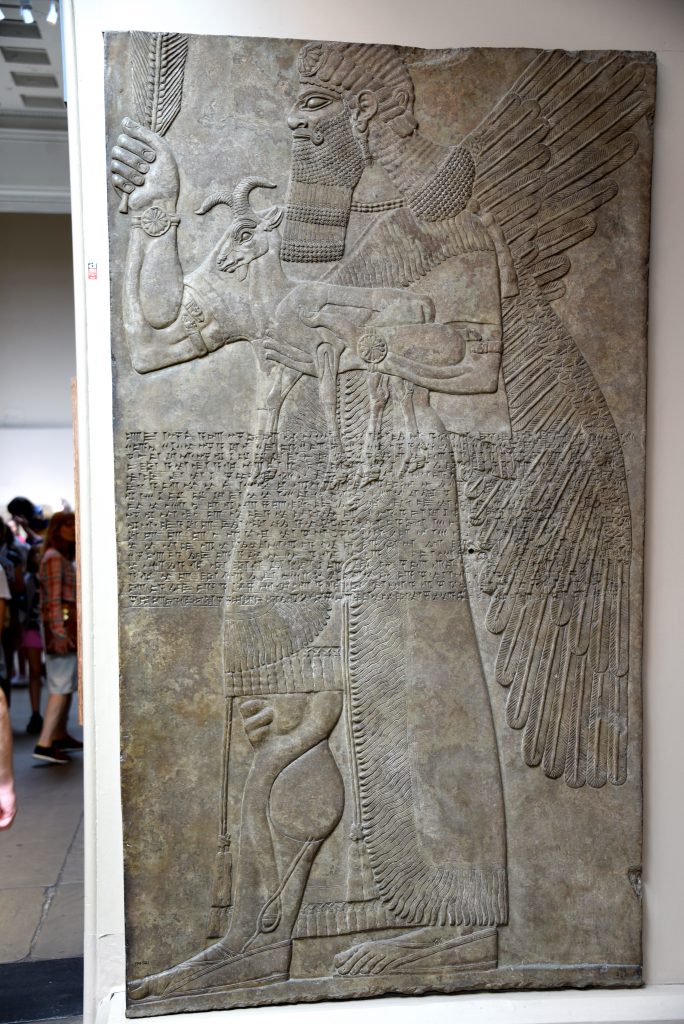

The large rectangular bas-relief, on the left, is 224 cm in height and 127 cm wide. In the British Museum, it is in Room T, as panel 1. This relief was probably, one of a pair, which guarded an entrance into the private quarters of the king. As we can see, it depicts a standing human-headed and winged male figure, looking to the left. His right arm holds a large ear of corn (may represent fertility) while his left arm holds a goat. He does not wear a horned helmet, instead, his head is encircled by a diadem with a rosette on the front. He does not hold a bucket, either. His scalp hair is long at the back reaches his shoulders. He has a prominently carved curly (upward) moustache and a magnificent long and curly beard (typical of a carved Assyrian figure at that time).

A human-headed and winged standing Apkallu (sage, genie, guardian, super-creature, or protective spirit). He holds a goat and a large ear of corn. Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

At the lower neck, there is a double-beaded necklace, which is held in position by a tassel at the back. There is an earring in the left ear. A very similar earring was found within the so-called “Queens Tombs” beneath the same palace in the late 1980s by the Iraqi archaeologist Muzahim Mahmood and his team. The figure wears a kilt, the lower margin of which ends with long tassels at the knee. An elegant fringed, short-sleeved, rope covers the body and both shoulders. The right leg, from the knee and below, appears uncovered by any type of clothes.

The Apkallu’s anatomical landmarks and contours of the arms and right leg muscles are prominently depicted in an exaggerated manner (just like a body builder’s), to convey the powerful nature of the creature. The skin folds on the right patella and the hypertrophied right calf are well expressed (had the sculptor studied anatomy?). There is (or what appears to be) a prominent superficial vein “beneath” the skin of the lower right leg. The creature wears sandals and has two pairs of wings.

The head of the Apkallu. He does not wear a horned cap (unlike other human-headed Apkallus). Instead, he wears a diadem. There is a rosette on the front of the diadem. The mustache’s ends are curled upward. There is an earring and the lower neck is surrounded by a double-beaded necklace. Note the hairstyle and the arrangement of the curls of the beard and lower end of the scalp hair. Part of the fringed rope also appear on the left shoulder. He looks to the left, in a sharp rigid look! Detail of Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

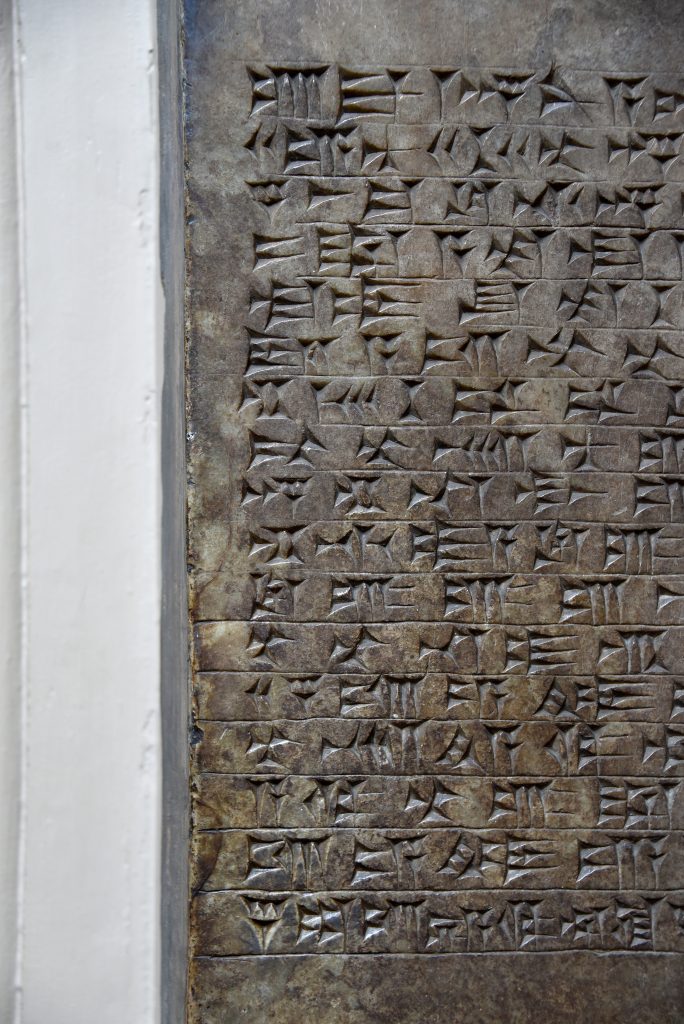

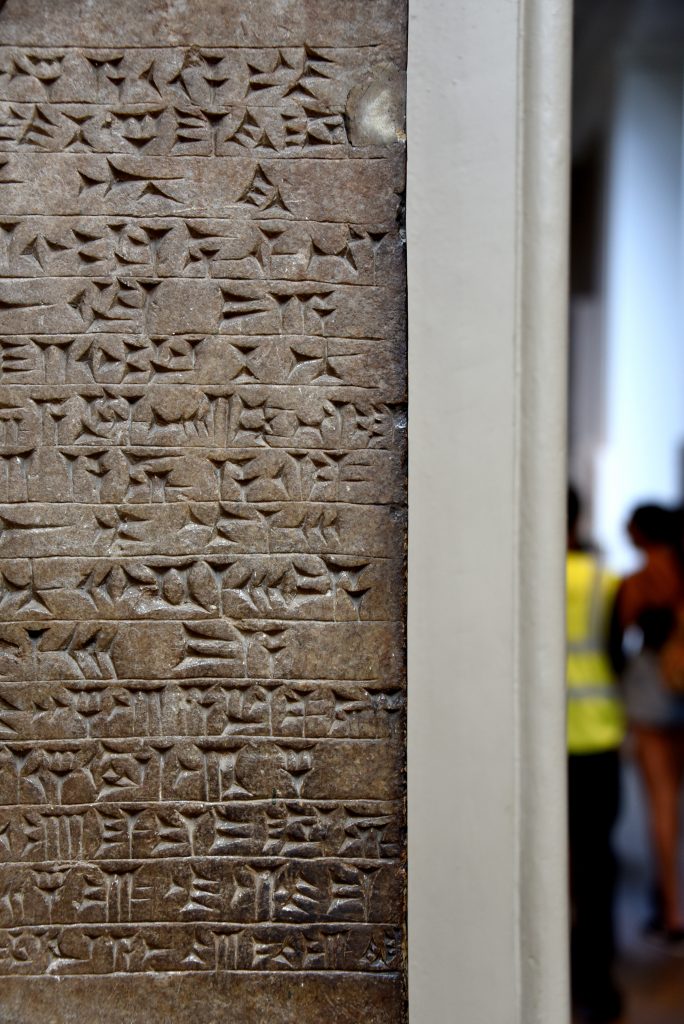

Above the elbows, there are armlets (with what appears to be ram-head decorations) while at the wrists, there are bracelets (with rosettes). The Apkallu’s way of holding the goat is very realistic. His left palm holds the animal’s abdomen and chest (between the thumb and other fingers) and in the space between the forelegs, he very slightly presses the animal against his chest. The goat appears comfortable and holds its head upright looking to the left. The animal’s facial and anatomical details are perfectly carved, as well. The “Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs horizontally across the middle part of the relief. There are 17 lines of very clear cuneiform. The text starts from the left, a couple of centimetres behind the left edge of the panel. All cuneiform lines share a common starting point as if there is an imaginary vertical line to mark “go”.

Looking closely at the relief (in my case, I zoomed-in with my AF-S NIKKOR 28-300 mm f/3.5-5.6G ED VR lens and Nikon D750 camera), we can see that the rope is embroidered with palms, cones, or “pomegranates”) and a surprise, a very tiny figure of the same goat! The tiny goat is also embroidered on the margin of the right sleeve.

The goat held by the Apkallu. Note the facial details and the exquisitely carved horns. Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This is the upper right arm of the Apkallu. A sleeve surrounds the limb and its margin is embroidered with a date, pomegranates(?), and cones. In addition, at the lower part, there is a tiny goat standing on a palm tree. The goat is very similar to the one which is held by the Apkallu. The ram-headed ends of the armlet also appear, surrounding the biceps muscle. Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The right hand of the Apkallu. He holds a large ear of corn and wears a bracelet with a 13-petaled rosette at the wrist. Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Apkallu wears sandals; a trace of faint red/orange color can be seen covering the sandal’s sole/footbed. Note the details of the long tassels in front and behind the lower leg. A superficial vein runs from the right calf to the lower leg, as a cord-like structure and disappears beneath the sandal. The fringes of the rope and the tassels also appear. Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The “Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II on the panel. Note how the horizontal lines, separating the inscriptions, were carved. There are 17 lines of cuneiform inscriptions. The heights of the horizontal spaces housing the inscriptions are not even. Some of the separating horizontal strokes reach the margin of the panel while others don’t. Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Part of the fringed rope showing its marginal tassels. A band of 6 embroidered 8-petaled rosettes appears above the tassels. Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Part of the fringed rope which covers the left lower leg. The edge of the rope is a narrow crisscrossed band. Above it, and along the edge, there are embroidered motifs of what appear to be cones or plants interconnected by horizontal stems. Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Note how the feathers of the Apkallu’s wing were carved and the overlying “Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II. Two rounded holes appear, seemed to be caused by nails (?), during transportation(?). The holes are cuffed by a small area of alabaster fracture, which had erased some of the inscriptions. One of the holes was filled in with modern cement(?). Detail, Panel 1, Room T, door “a” of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Genie and the Deer

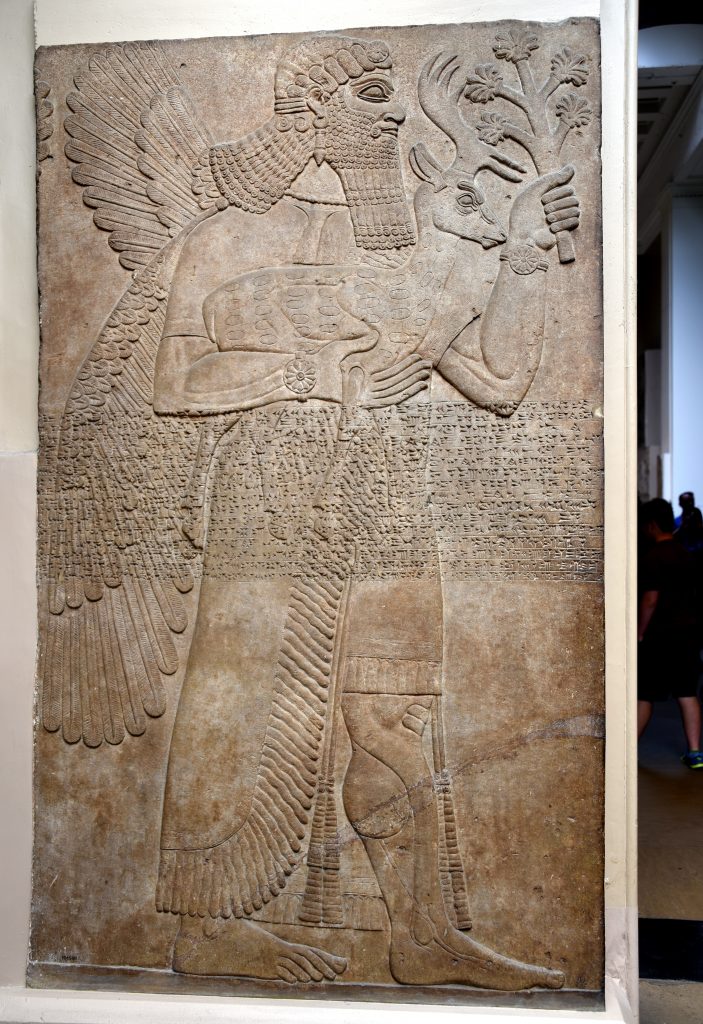

Just opposite to the aforementioned relief, there is another large alabaster bas-relief of an Apkallu. This relief is 225 cm in height and 135 cm wide. It was decorating the right half of the entrance into the King’s Throne Room B. The overall depiction of the Apkallu is almost the same but there are some differences. Some of the dissimilarities are expected because this Genie was depicted from the right side, not the left, for example, he and his deer look to the right. I will compare him with his fellow Apkallu below.

1. The size of the skull appears smaller, note the height from the eyebrow to the top of the skull (vertex).

2. Hair: Superficially, the scalp’s hair style and arrangement look the same. The hair at the back of the head is a little shorter and there are horizontal feathers from the wing behind the lower curly end. The size of the beard curls and scalp is a little bit larger and their number is smaller accordingly. There are fewer rows of curls. There are two large hair curls below the back of the diadem. The hairline at the forehead is obscured by the diadem.

3. Diadem: Though the diadem designs appear alike, they are actually different, including the way of placement and folds. The rosette at the front of the diadem appears complete and was portrayed “en profile”. There may be another one on the left (not shown), it is also smaller.

4. There is a prominent “naso-labial fold” – a fold of skin from the nostril to the outer end of the mouth (moustache). Perfect anatomy!

5. The depiction of the eye is less elongated and we can see an “iris” within the eye globe. The inner corner of the eye (inner canthus) is angled downward.

6. The mustache’s ends are curled downward, not upward. Therefore, the corner of the mouth is obscured. We can recognise a band of beard-free skin below the lower lip.

7. The outer end of the eyebrow is pointed, not rounded. The eyebrow appears shorter.

8. The upper part of the nose’s bridge is concave, not convex. The beard-free area of the cheek appears flat. His fellow displays a prominent cheek (eminence).

9. The earring is different. The anatomical details of the external ear are also obviously different. The necklace is composed of a single line of beads.

10. He wears no armlet! However, his bracelets are different. The tips of the flower petals are pointed, not rounded.

11. The area at the upper anterior chest (in front of the upper sternal bone) is different, including different clothing and arrangement.

12. The Genie carries a small (young) deer in a very similar way (of embracement), but he uses his right arm and palm. The animal’s depiction and specific details are superb. The left-hand holds what appears to be a palm branch, a typical Assyrian motif.

13. He is bare-footed! The superficial vein of the left lower leg descends further downwards to the mid-foot. Another shorter vein appears behind the “inner malleolus” (bony prominence at the ankle). The left calf appears a little smaller.

14. The long tassels (in inform and behind the left leg) are completely different. The lower rope’s small rows of tassels are also different.

15. There are two folds of the skin folds in front of the patella (knee area), not three.

17. The embroidered shapes on the rope are different.

18. The wings are smaller.

16. The “Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II runs horizontally across the middle part of the relief. However, the upper line of the cuneiform inscriptions of the text runs across the tip of the left elbow joint, proximal part of the right index finger and adjacent hand, and the lower surface of the right forearm. If we compare both reliefs, side by side, we can see that the inscription runs exactly horizontally through both slabs, in continuity. The upper half of the body of the Genie who holds the goat, however, appears taller and more heavily built. This explains why his upper body half and upper limbs are not covered by the inscriptions. Behind the right edge of the panel, the endings of the 17 lines of inscriptions are not parallel, this is to be expected, as this is the end of the text, not the beginning.

A human-headed and winged Apkallu, holding a deer in his right arm. The left hand carries a palm branch. The animal is a Persian fallow deer (of the species Dama Mesopotamica). This deer still lives in Northern and Northern-Eastern parts of Iraqi Kurdistan (in the area between Iraq, Iran, and Turkey, where the heartland of the Assyrian Empire is very close). The Apkallu wears a kilt and a fringed rope containing many tassels. He is bare-footed. Panel 30 (right half), Room B of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. This room’s door leads to the Royal Throne Room. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This is the head of the Apkallu. Although superficially and after rapid skimming, the face, hair, diadem, eyebrows, eye, nose, beard, necklace, and earring may resemble those of his fellow, but there are many differences. The Assyrian sculptor intentionally made these differences, implying that he had depicted and portrayed 2 different Apkallus. Detail, Panel 30 (right half), Room B of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. This room’s door leads to the Royal Throne Room. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Assyrian sculptor portrayed a “buck“; this is the male Persian fallow deer, which still lives in the area. The Apkallu holds a palm branch in his left fist. He wears a bracelet with a 12-petaled rosette; the tips of the petals are pointed, not rounded. The animal’s anatomical landmarks and details were exquisitely carved. The oval shapes on the deer’s body represent the white skin spots of the animal; they are smaller on the face! Detail, Panel 30 (right half), Room B of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. This room’s door leads to the Royal Throne Room. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Apkallu’s left upper arm. The margin of the sleeve was embroidered with a band of geometric motifs; the deer was not included in the embroidery. Because the left elbow joint is flexed, the left biceps muscle (below the sleeve) appears in contraction and is prominent; what a sculptor he was! Detail, Panel 30 (right half), Room B of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. This room’s door leads to the Royal Throne Room. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Apkallu is bare-footed. Two superficial skin veins are seen on the inner aspect of the left ankle and foot. Detail, Panel 30 (right half), Room B of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. This room’s door leads to the Royal Throne Room. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Part of the “Standard Inscription” of Ashurnasirpal II on the middle part of the relief. The 17 lines of the cuneiform inscriptions don’t end at an imaginary vertical line before the left edge of the relief; rather they have different ending points and the terminal cuneiform signs of 3 lines touch the edge of the panel. Detail, Panel 30 (right half), Room B of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. This room’s door leads to the Royal Throne Room. Neo-Assyrian period, 865-860 BCE. Housed in the British Museum, London. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

From this, in-depth look, we can assume that the artist obviously depicted and portrayed two different Apkallus and placed them in two different areas within the palace. Did they have different names, function, or power? Or was it was just haphazard placement, distribution and decoration of the palace walls? I wonder if the artist thought, even for fraction of a second that his legacy would survive and travel to a very far land, called “the United Kingdom” and its indescribable British Museum?

Though, it is saddening to remember the graphic destruction of the ancient city of Nimrud. I am thankful to Sir Layard, Rassam, Mallowan and the many Iraqi archaeologists, who have spent their lives excavating, rebuilding, preserving, storing, and displaying the rich heritage found in Nimrud.

“Sometimes it is the people no one can imagine anything of who do the things no one can imagine” Alan Tuning.