Stretching from the beaches of the Adriatic Sea to the banks of the Indus River, Alexander the Great’s empire was the largest the world had ever seen when he died in 323 BCE. His empire broke into several smaller kingdoms soon after, but his enduring legacy can be found in signs of Hellenistic cultural diffusion in ancient artifacts that survive today. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s latest exhibition, Pergamon and the Hellenistic Kingdoms of the Ancient World, is a testament to this cultural interaction and the footprint Alexander left in history far beyond what his imagination could have conceived.

Hellenistic Sculpture

This bust of Alexander may lack a nose, but it does not lack historical significance. Alexander’s image set the precedent for countless other portraits in the Hellenistic world. Even Roman emperors chose to be portrayed in Alexander’s idealized style in their own sculptures centuries later. It is important to examine what this image tells us, whether consciously or not, and how Alexander and other leaders used that to their advantage in consolidating power. Alexander’s hair falls in a center part. His face is youthful and unwrinkled, his eyes staring straight ahead at what is to come. Perhaps this hints at a desire to portray himself even-keeled and unflappable — after all, no one would follow a timid, uncertain leader into battle.

Portrait of Alexander the Great at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image © Caroline Cervera.

These portraits are of Alexander and a young man, presumed to be Hephaistion, Alexander’s constant companion from childhood. Hephaistion died of a fever just a year before Alexander and his death had a major impact on the king. The two were described as having an incredibly close relationship. Modern scholars have proposed theories of a romance between the two, but so far no ancient sources have been found that explicitly state this. Regardless, these portraits depict two young men who shared a deep bond. They were such good friends that Alexander, the most powerful man in the world, became so distraught upon Hephaistion’s untimely death that he stopped eating for days. He died the next year of a fever as well.

Alexander and a young man, likely Hephaistion, side by side at the exhibition. Image © Caroline Cervera.

Homer was a Greek poet best known for his epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. His works shaped culture in the ancient world, the Renaissance, and even modern times. This bust portrays Homer as a sage elder with a weathered face and is a testament to the artistic craftsmanship of the Hellenistic age. The skill required to sculpt the locks of his hair out of solid marble is remarkable.

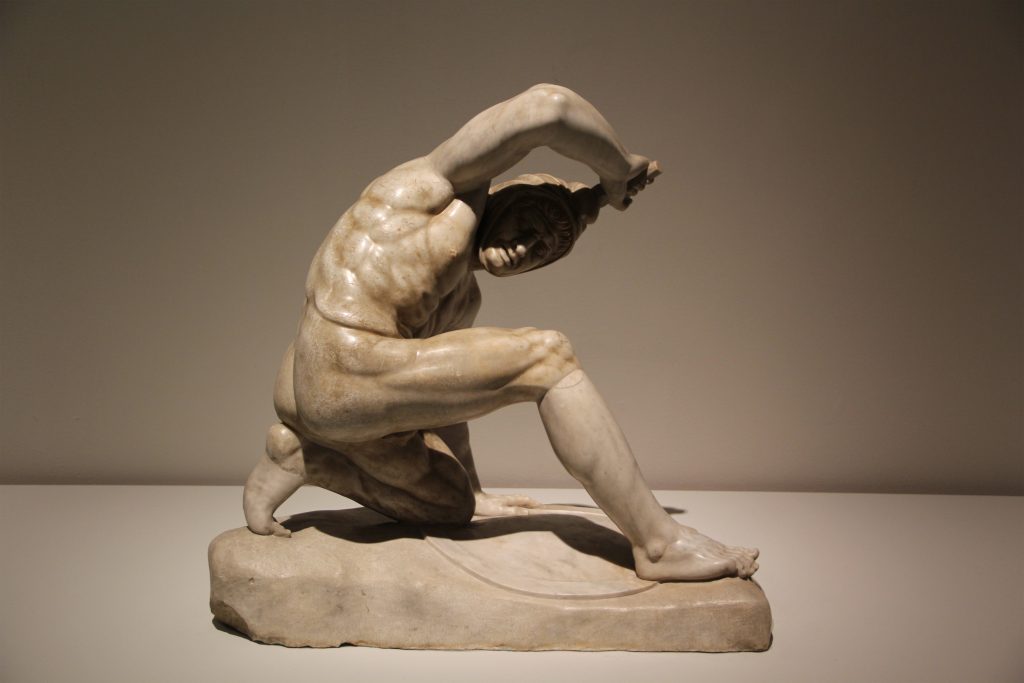

Other Hellenistic sculptures in the exhibition. Image © Caroline Cervera.

Cultural Exchange in the Hellenistic World

The lion hunt is a common motif in ancient art. One may recall the famous reliefs of the lion hunt of Ashurbanipal, now housed at the British Museum, stretching across the walls of his palace at Nimrud. While in Assyrian culture, the lion hunt was a staged event and meant to demonstrate the power of the king, Macedonian culture of Alexander’s day viewed it quite differently, as it was a rite of passage required before young men could sit at a banquet table.

Lion hunt motif. Image © Caroline Cervera.

This sculpture of a soldier comes from Persia, the region to the east of Macedonia and Mesopotamia, which was conquered by Alexander and later ruled by one of the Hellenistic kingdoms that succeeded him, the Seleucids. The soldier’s origin is evident in his pointed helmet, which was typically worn by Persian soldiers. It is a Roman copy of a Greek sculpture, demonstrating how far Persian culture traveled as the result of the cultural exchange the Hellenistic unification facilitated.

Persian soldier. Image © Caroline Cervera.

This statuette of a veiled dancer is part of the museum’s permanent collections and is one of my favorite pieces at the Met. The piece was created in Alexandria, Egypt — one of at least nineteen cities founded by Alexander and named for himself — where dancers like this woman would perform through both miming and dancing. I am always amazed by how much movement the artist communicates using the intricate folds of the figure’s garment. The technique makes a single piece of solid metal come alive over two thousand years after its creation.

Statuette of a veiled and masked dancer, found in Alexandria, Egypt. Image © Caroline Cervera.

Hellenistic Jewelry

The gold jewelry on display in this exhibition shone like the sun among the marble sculptures surrounding it. The Greeks, who had previously spurned ostentatious display of wealth through jewelry, came into contact with kingdoms in the ancient Near East and began to embrace the art through the production of jewels like those in the exhibition. See the minute attention to detail displayed in the pieces below.

Piece featuring a bust of Athena. Image © Caroline Cervera.

Light glints off this bust of Athena. Image © Caroline Cervera.

This golden ornament is comprised of a wide array of small chains, links, and designs. Image © Caroline Cervera.

The exhibition will be at the museum through July 17, 2016. Over one-third of the pieces on display are on loan from the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, making this an excellent opportunity to view objects that do not normally reside on this side of the Atlantic. Admission is free with admission to the Met. Click here for more information.