To mark Ancient History Encyclopedia’s latest international partnership with Humanidades Digitales CAICYT in Buenos Aires, Argentina, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande, a researcher at the Seminario de Edicion y Crítica Textual (SECRIT-IIBICRIT) of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), about the state of the digital humanities in Argentina, in addition the potential implications and promise of digital research in the Hispanosphere and wider world alike.

JW: Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande, thank you for speaking with me and welcome to AHE. What is the state of the “digital humanities” in Argentina and Latin America? What specific challenges are encountered in the region, and what can researchers abroad do to assist?

GDRR: Every time someone asks me this question, the first thing I do is to say that the “digital humanities” or “DH” is not the same as the humanidades digitales or “HD” in Spanish. While the digital humanities is nowadays an expanding scientific field with a clear tradition in relation to the humanities, computing, computational linguistics, or even the “digital scholarly edition” in most Anglophone institutions — not just those of USA or UK, but also countries like Germany or the Netherlands where English is a scientific koiné — we cannot say the same for the HD or Hispanophone nations.

GDRR: Every time someone asks me this question, the first thing I do is to say that the “digital humanities” or “DH” is not the same as the humanidades digitales or “HD” in Spanish. While the digital humanities is nowadays an expanding scientific field with a clear tradition in relation to the humanities, computing, computational linguistics, or even the “digital scholarly edition” in most Anglophone institutions — not just those of USA or UK, but also countries like Germany or the Netherlands where English is a scientific koiné — we cannot say the same for the HD or Hispanophone nations.

The HD, mostly in Latin America, has very recently begun to define itself as a field that did not experience the flow and currents of “humanities computing.” This is important since it is not a question of thinking that the DH has landed upon a tabula rasa. Sometimes, the problem is that our academies have established other disciplines that have interpreted the DH via a different theoretical approach. (For example something like “media studies” as ciencias de la comunicación.) The impossibility of reading scientific texts in English — some fundamental texts did not circulate in our universities and there is lack of investment in technology in areas like computational linguistics — has shaped the DH in entirely different ways; in my opinion, the HD builds its own canon based on the knowledge and know-how of “local and the global heroes.”

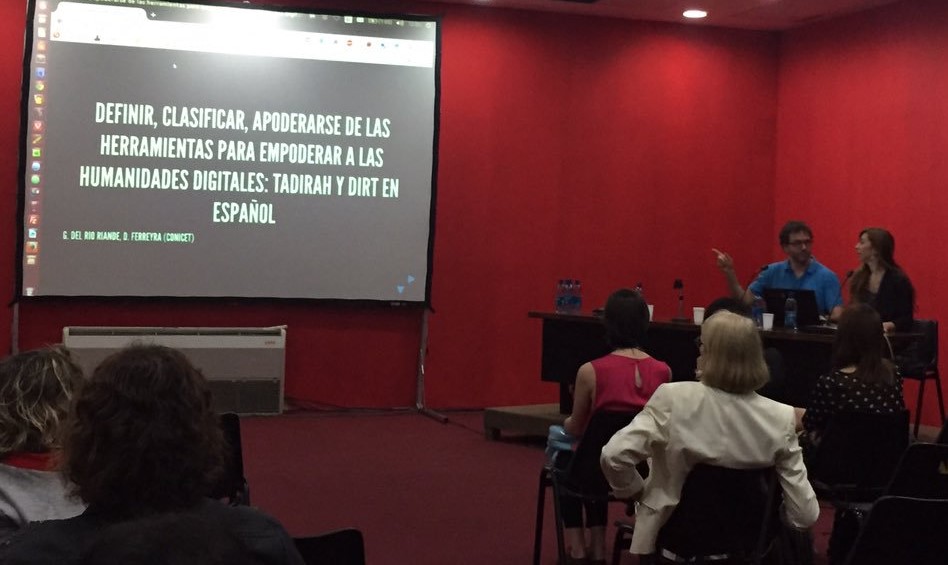

International Congress of the Humanidades Digitales in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 2016. Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande is on the left side of the picture. (Photograph: Courtesy of Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande.)

I can only speak about my country, Argentina, as Latin America is a wide space that not only includes countries but also places in which Spanish is spoken as a main language for communication. In the case of Argentina, one of the main obstacles for the consolidation of a scientific field and of a solid academic discourse in the HD is the scarcity of funding for large-scale research projects in the humanities and the focus of our academics in more theoretical studies. Thus, with the exception of the individual work of some Argentines, such as those carried out by CONICET’s Seminary of Scholarly Edition and Textual Criticism (SECRIT) for the coding system of the Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison or for specific projects that involved Spanish researchers such as Francisco Marcos Marín, there has not been a clear communion between research in the humanities or social sciences and the digital sciences. (I should also add that in Argentina, for instance, Lev Manovich is regarded as a main figure for the the HD.) I think that a good way of fostering research in the HD and creating a global collaboration is when researchers that have already started working on the DH in other parts of the world “invite” other communities to be part of their projects. That is why we are very happy to start our collaboration with AHE!

I would like to note that one important aspect of HD in Latin America is the emergence of associations that work with researchers and university staff, but not inside those academic spaces: RedHD of Mexico, the Argentine Association of Digital Humanities (AAHD), and now associations that were founded last year in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Uruguay. All of these offer a testimonial to the interest and also the considerable difficulties of transforming the HD into a scientific field inside academia. Since I started working for the AAHD in 2013, we have organized two conferences (one international) and more than 20 events, including THATCamps, international symposia, workshops, seminars, conferences, talks, etc. The momentum continues to grow, day by day.

“I think that a good way of fostering research in the HD and creating a global collaboration is when researchers that have already started working on the DH in other parts of the world “invite” other communities to be part of their projects. That is why we are very happy to start our collaboration with AHE!”

JW: Tell us about the activities of HD CAICYT — what are its aims and goals? What kinds of projects and activities is it currently undertaking?

LINHD members present research findings at UNED in Madrid, Spain. (Photograph: Courtesy of Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande.)

GDRR: I have been working at CAICYT since 2014 and thanks to its Director’s generosity, I contributed to the first Argentine institutional project in the HD: Research Methodologies in Digital Tools for Research in Humanities and Social Sciences (MHeDI). Together with Mela Bosch, we started thinking about how we could knock down the barriers that inhibited the HD to become better established. We realized we had to identify what the HD was, and what had been done before. We then worked with people from Centro de Investigaciones en Mediatizaciones (CIM) — like Virginia Brussa from Universidad de Rosario — on a survey focused on digital methodologies. We also started translating valuable tools such as DH taxonomies (like Tadirah), and enhanced their use through the possibilities of semantic interoperability, which TemaTres facilitates. In turn, we also developed a set of best practices for the standardization of methodologies and the scientific evaluation for the HD in Argentina.

HD CAICYT seeks to combine the conceptual and organizational model of the laboratory with another one based on collaborative work to stimulate the scientific development of the HD in Argentina: Projects, resources, tools that have academic, social and cultural value and that are scalable and reusable. HD CAICYT aims to serve to multiple audiences, inside and outside the scope of research and academia. Furthermore, HD CAICYT develops and tests digital tools, provides interested users with scientific material — open access articles, presentations, course news, etc. — and models of good practice for research and training in digital humanities and interdisciplinary research. Our main areas of interest are:

- Taxonomies in the digital humanities

- Tools and resources in the digital humanities

- Data exploitation and visualization

- Best practices in the digital humanities

I am gratified and pleased that HD CAICYT involves more people these days, and it has worked on many collaborative projects with CIM, Laboratorio de Innovación de Humanidades Digitales (LINHD) in Spain, Pelagios Commons, Big Data Machine, and now we are beginning a new relationship with AHE.

Diego Ferreyra, one of HD CAICYT members, discusses the importance of Tadirah. (Photograph: Courtesy of Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande.)

JW: Technology plays a defining role in reshaping the humanities at the dawn of the 21st century. Which technologies does CAICYT utilize in their projects, and which technologies do you hope to utilize in the near future?

GDRR: We are very aware of the possibilities and limitations of technologies in a country such as Argentina, where sometimes technology is more a barrier than an advantage, James. The first thing we do is to look for bridges of collaboration. LINHD is our key ally and partner, and many of our projects would not be a possible with them. We also aim to use open source technologies and to reuse as much as we can. In reusing and recycling source technologies, we find productive innovation. We are very proud that we use some fantastic fantastic software, such as Tematres, which was developed by one of HD CAICYT members, Diego Ferreyra. We not only use this for working on controlled vocabularies, but also for enhancing and exploiting our HD projects.

JW: I wanted to ask one specific question about the Mediaeval Iberia Project, which was funded through the LINHD team at Spain’s Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) and Pelagios Commons, the latter of which also has ties to AHE; in your own words, what is the importance and potential of this project, and how do you think it shall help scholars of medieval Spain?

GDRR: We were very happy when it was announced that the LINHD team at UNED had been awarded with one of the Pelagios research grants. My proposal is focused on extending the use of Pelagios tools and resources to the medieval Iberian world. I noted we could use every important source for Spanish philology (like the Biblioteca Digital de Textos del Español Antiguo (BIDTEA) from the Hispanic Seminary of Mediaeval Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison) to help scholars identify medieval places and add information about them.

These enriched texts improve research, but they can also be used with and by students. The team at LINHD and CAICYT carried out and coordinated work; indeed, we are still working on it and especially on an automatic tagging tool for place names in Spanish. It was very enriching for us to commence contact with groups that had already started working on geographic information systems (GIS) and semantic web technologies applied to antique texts. I believe that the Mediaeval Iberia Project has a lot of possibilities of development in many aspects like cultural heritage and even tourism too.

Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande presenting research on data curation in Chile. (Photograph: Courtesy of Dr. Gimena del Rio Riande.)

JW: Gimena, if I may, might I ask you tell us a bit about your academic background and personal interest in the digital humanities? How did you become so intimately involved in so many projects?

GDRR: I did my undergraduate courses in Argentina at the Universidad de Buenos Aires (Faculty of Philosophy and Literature), and I have a doctorate in Romance philology from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid. I also completed a master’s degree in relation to library science and cultural heritage. When I was working on my Ph.D. — my research consisted upon a review of on a critical edition of Denis I of Portugal’s songbook — I started using online digital resources that helped me discover many aspects of the songbook I had never perceived before from a close reading (citing Moretti). For instance, I discovered how metrical and melodic patterns from Occitan poetry were adapted in some of Dinis’ poems.

Although some hypotheses had already been studied, I could now see a “big picture,” and I found more testimonies using scientific methodologies. Soon after, I had the chance to work in many important Spanish “New Technologies Projects,” including MedDB (Base de datos da Lírica Profana Galego-Portuguesa) and BIESES. In 2011, I worked with Elena González Blanco from UNED on our first Digital Humanities project: ReMetCa. We finally established a big DH project in Spain, which is now LINHD-UNED. It is the first DH laboratory in Spain and uses the Spanish language. We started many projects and collaborations with projects all around the world that I really enjoy. I would tell those interested in the digital humanities or humanidades digitales that I have always been able to learn something from someone elsewhere in the world!

Gimena del Rio Riande is a Researcher at the Seminario de Edicion y Crítica Textual (SECRIT-IIBICRIT) of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Dr. del Rio Riande gives courses on Romance philology and the digital humanities at the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina and LINHD in Madrid, Spain. Her main academic interests deal with the scholarly edition and study of the medieval lyrical poetry and the development, use, and methodologies of scholarly digital tools. She has been working since 2013 on the creation of a digital humanities community in Argentina, and she is nowadays the Vice President of the Asociación Argentina de Humanidades Digitales (AAHD). She organized the first National Conference on Digital Humanities in Buenos Aires in 2014. Dr. del Rio Riande coordinates the following Argentine digital projects: Diálogo Medieval, Obras Completas de José Luis Romero, and Humanidades Digitales CAICYT-CONICET. She also is a key contributor to the Spanish language digital projects of the PoeMetCa group at LINHD, among others.

Gimena del Rio Riande is a Researcher at the Seminario de Edicion y Crítica Textual (SECRIT-IIBICRIT) of the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Dr. del Rio Riande gives courses on Romance philology and the digital humanities at the University of Buenos Aires in Argentina and LINHD in Madrid, Spain. Her main academic interests deal with the scholarly edition and study of the medieval lyrical poetry and the development, use, and methodologies of scholarly digital tools. She has been working since 2013 on the creation of a digital humanities community in Argentina, and she is nowadays the Vice President of the Asociación Argentina de Humanidades Digitales (AAHD). She organized the first National Conference on Digital Humanities in Buenos Aires in 2014. Dr. del Rio Riande coordinates the following Argentine digital projects: Diálogo Medieval, Obras Completas de José Luis Romero, and Humanidades Digitales CAICYT-CONICET. She also is a key contributor to the Spanish language digital projects of the PoeMetCa group at LINHD, among others.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to AHE by Gimena del Rio Riande have been done so as a courtesy, and we thank her warmly for their generosity. Interview edited by James Blake Wiener for AHE. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. © AHE 2017. Please contact us for rights to republication.