Cover for “Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and History of the Iraqi Cuisine.” (Photo, courtesy of Nawal Nasrallah.)

Mesopotamia (from the Greek, meaning “between two rivers”) was an ancient region in the Near East, which corresponds roughly to present-day Iraq. Widely regarded as the “cradle of civilization,” Mesopotamia should be more properly understood as a region that produced multiple empires and civilizations rather than any single civilization. Iraqi cuisine, like its art and culture, is the sum of its varied and rich past. Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine, by independent scholar Nawal Nasrallah, offers more than 400 recipes from the distant past in addition to fascinating perspectives on the origins of Iraqi cuisine.

In this exclusive interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Nawal Nasrallah about the research behind her unique, encyclopedic cookbook, the origins of Iraqi cuisine, and her passion for cooking ancient recipes.

JW: Ms. Nawal Nasrallah, I bid you the warmest welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE)! Ahlan wa sahlan!

Nawal, I am very curious to know what motivated you to write this title, and what prompted your interest in ancient and medieval Iraqi cuisine? Before relocating to the United States in 1990, you were a professor of English and Comparative Literature at the Universities of Baghdad and Mosul. Have you always been interested in “food history” as a tangent to your other academic interests?

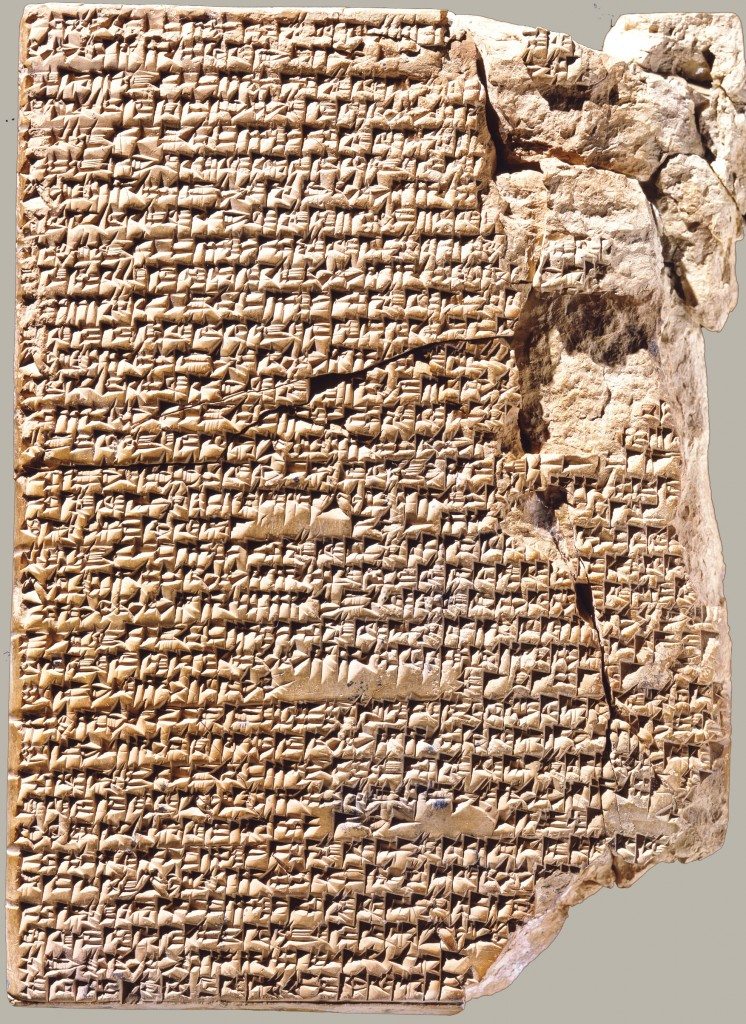

Reverse of the Cuneiform tablet of Babylonian stew recipes, c. 1700 BCE. (Yale Babylonian Collection, Tablet 4644.)

NN: First of all I would like to thank you for giving me the chance to talk about Iraqi cuisine, unjustifiably little known and rarely acknowledged in the general discussion of culinary history. Now to your question; as you mention, my career in Iraq was that of a university professor. My interests back then were totally focused on research in English literature, but I loved cooking and reading the few English cookbooks I could lay my hands on. But never in my wildest dreams did it occur to me that within years of my arrival to the US in 1990, I would be calling myself a “food writer” with several food-related books under my belt. My previous training in research was indeed quite helpful in this respect. While in the US, Iraq was so much in the news, and I was often asked if I knew of any Iraqi cookbooks in English.

There were none that I knew of, and I personally felt that a cookbook on Iraq should be given a place among the international cuisine books on shelves of libraries and bookstores. It did not occur to me though, at the time, that I would be the one to do it. In 1996, after I suddenly lost my son at the age of 13, it was extremely painful for me to handle food; it was just loaded with memories, too painful to remember. To get around this, I gave myself a mission: Write a cookbook about the food we shared and loved, dedicating it to his memory.

JW: Something that I think will surprise many AHE readers is the fact that modern Iraqi cuisine has retained much in the way of its ancient Mesopotamian roots; from delicious breads to tasty stews, sweet layered cakes and to grilled kebabs, the culinary history of Iraq reflects the palates of successive ancient civilizations. One should mention too that ancient Mesopotamian cuisine shaped the cuisine of the ancient Persians, medieval Arabs, and Ottoman Turks.

What specific challenges did you face in writing this book, and was it difficult to uncover the true provenance of the many dishes presented in Delights from the Garden of Eden?

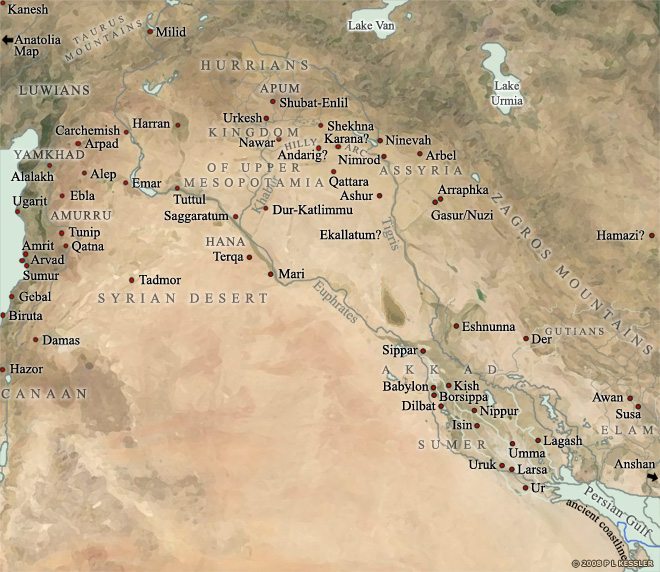

A general map of Mesopotamia, covering the period from 2000-1600 BCE. (©PL Kessler/The History Files. Republished with the author’s permission. Original image by P L Kessler, 2012.)

NN: The challenge was writing a huge book like mine and spending about six long years working on it, hoping that at least when done and finished, I would succeed in convincing a publisher of its novelty and worthiness. This did not happen. I had to self-publish the first edition that came out in 2003, and boy, am I glad I followed my instinct and did it! After several years, it attracted the attention of a British publisher, Equinox Publishing, and I am thrilled that Delights from the Garden of Eden is now available in its second edition.

I cannot really say that the process of uncovering the roots of many of the dishes in Delights was a hassle — it was not. I was fortunate to have at my disposal sources from ancient Mesopotamia and medieval Baghdad, which were instrumental in tracing not only sources of dishes, but also in deflating the commonly recycled notion that Iraqi cooking has no character or roots of its own or that it is derivative, being heavily influenced by Persian, or Turkish, or Ottoman cuisine.

With the evidence we have today of ancient Mesopotamian cuisine, we can say with confidence that ancient Persian culinary culture had a lot to learn from the indigenous Mesopotamians whom they politically ruled. In fact, according to modern historical studies, the date when the Persians took over the region (539 BCE) was significant politically only because they “left most local traditions intact,” and employed native officials for most tasks, as Dr. Daniel Snell writes in his Life in the Ancient Near East 3100-332 BCE. He further adds that “although taxes flowed to the capital in what is now Iran, little in the way of cultural influence flowed the other way.” (pp. 99, 102.)

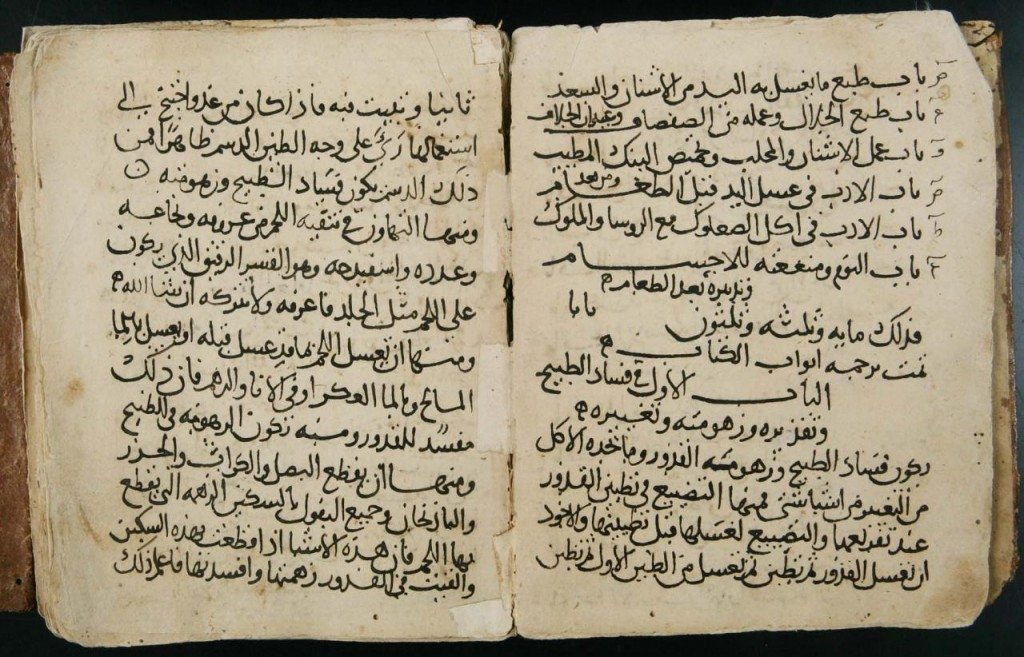

Folios of Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s tenth century CE cookbook. (Fols 7v-8r. The National Library of Finland, signum Coll. 504.14 [Arb rf].)

The impact of the Baghdadi Abbasid cuisine on the affluent Ottoman kitchens of Istanbul can no longer be downplayed given what we know today. Suffice it to say that the first Ottoman cookbook, Kitabu’t-Tabeeh, written in the 15th-century CE, was in fact mostly a translation of al-Baghdadi’s popular cookbook, Kitab al-Tabeekh. The Ottoman version was executed by Muhammed ibn Mahmud Şirvani (also Romanized as “Mehmet bin Mamoud Shirvani,” c. 1375-1450 CE), who was the court physician to Sultan Murad II (r. 1421-1444, 1446-1451 CE). In the centuries to follow, the Ottoman kitchen undoubtedly developed and refined such inherited traditions but from what I see of our cooking today, I doubt that it had a significant impact on Iraqi mainstream cooking. Names of dishes are not always dependable criteria.

Cover image of al-Baghdadi’s cookbook from the 13th-century CE: “Kitab al-Tabeekh.” (1934 edited Arabic edition.)

JW: Nawal, you used rare Babylonian tablets, medieval Baghdadi cookbooks, and other primary source documents in order to research Delights from the Garden of Eden.

Do you have a favorite source? If so, which one, and what makes it your favorite? How large are these surviving sources?

NN: Of the primary sources I used in my research for Delights, three were pivotal: the ancient Babylonian recipes written on three cuneiform tablets, the tenth century CE Baghdadi cookbook by Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq, and the 13th-century CE cookbook by Ibn al-Kareem al-Baghdadi. (Both of these cookbooks are titled Kitab al-Tabeekh or “Cookery Book” in English.) These were the sources that made me see a pattern of continuity in culinary practices of Iraqi cooks across millennia — a unique insight not to be encountered in other world cuisines — largely due perhaps to lack of evidence.

With these sources I found myself in an enviable position, which enabled me to see how Iraqi cuisine evolved and developed from ancient times, through the Middle Ages, to what I grew up on eating and cooking. Until I discovered these sources while researching for Delights, it never occurred to me that a staple like today’s marga (stew) has been a staple since ancient times. The Babylonian stew recipes — 25 of them — are an amazing testimony to its ancient roots; similarly, stew recipes loomed large in the two extant cookbooks from medieval Iraq .

Without dispute, my favorite is al-Warraq’s cookbook. It is the earliest medieval cookbook, worldwide, to have survived. With its hugely extensive scope — consisting of 132 chapters with around 600 recipes — it is an unrivaled culinary treasure, and it was my privilege to be able to translate it into English and share its joys with non-Arabic readers.

JW: For those of us who have very little aptitude in the kitchen, how difficult would you say it is to master the art of Iraqi cooking? In terms of the key ingredients found in ancient and medieval Iraqi recipes, Iraqi cuisine seems to be far less demanding than I had initially thought.

NN: Quite right. Most of the ingredients required to create Iraqi dishes may easily be obtained from mainstream supermarkets, with few exceptions such as our special spice-mix of baharat, noomi Basra (dried lime), and the favorite Iraqi spicy condiment of amba (pickled mango).

For more information on these uniquely Iraqi ingredients, I would ask readers to visit this link concerning ingredients via my website.

It is the cooking techniques that make the difference, and they vary from the basic to the complex. I should expect cooks with basic cooking experience to easily master the Iraqi staple dishes of marga wa timman (stew served with a side of rice), the many side dishes offered (both with meat and vegetarian), salads, some desserts. But some of the stuffed dishes — which distinguish Iraqi cuisine — can indeed be somewhat challenging, but I am sure with enough practice even these can be done with great success.

JW: In the 11 years since its first publication, Delights from the Garden of Eden has become an underground bestseller. During this time, you have written two more books: Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens (2007) and Dates: A Global History (2011).

May I inquire as to the projects you are currently undertaking? Can we expect more cookbooks or culinary histories in the near future?

NN: Well, right now I am working on a book about history of Arab food and an English translation of a 14th-century CE anonymous Egyptian cookbook entitled Kanz al-Fawa’id fi Tanwi’ al-Mawa’id, which I translate as Infinite Benefits of Variety at the Table. This is an important culinary document because it is the only one that came down to us from medieval Egypt. So as you see, I have my hands full right now. It is my ambition, though, to translate into English the rest of the medieval Arabic cookbooks and pamphlets — five to six volumes — which will fill a wide gap in our knowledge of the world material culture in which the impressive Arab contribution remains unknown. Once published, I am sure Western researchers in this most vital and interesting aspect of material culture will have at their fingertips the much-needed tools to explore the field with more solid and dependable results, giving credit where credit is due.

Hopefully, I will have the time and energy to follow up on these as soon as I am done with what I am working on now. It would definitely have been helpful to have had luck in securing a research grant for this kind of colossal task. I have been trying, but no luck as of yet.

JW: I purposefully arranged our interview to coincide with the US Thanksgiving holiday and upcoming seasonal festivities in the Americas and Europe. To conclude our interview, could you share or recommend a suitable dish for the holiday season?

NN: I would recommend the “Pregnant Chicken.” While I was still living in the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, I was once invited to dinner, and a delightful huge bird roasted to beautiful crispness attracted my attention. At first, I thought it was a large duck, but it turned out to be just a regular chicken stuffed in the cavity as well as underneath the skin with an aromatic spicy mixture of cooked rice and diced vegetables, raisins, and almonds. It looked splendidly huge and puffed up, so my kids nicknamed it the “Pregnant Chicken.” It has been a staple for our festive occasions ever since; it’s really the perfect dish for Thanksgiving. It is really scrumptious and definitely worth trying!

JW: Nawal, I thank you so much for your time and consideration. On behalf of everyone at AHE, I wish you many adventures in research and a happy holiday season.

NN: You are most welcome, James. It was a pleasure to speak with you. I wish you all a happy holiday season, and hopefully this interview will encourage your readers to try some of the wonderful dishes of Iraq!

Please read our book review of Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine.

Ms. Nawal Nasrallah is an independent Iraqi scholar, who is passionate about cooking and its history and culture. Previously, Nasrallah was a professor at the universities of Baghdad and Mosul, teaching English language and Literature until 1990. She is an award-winning researcher and food writer, who has been giving cooking classes and presentations on the Iraqi cuisine for a number of years. The first edition of her cookbook Delights from the Garden of Eden: A Cookbook and a History of the Iraqi Cuisine (Author House, 2003) was the winner of the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards 2007. (This title is also available as an iBook.) Her book Dates: A Global History (Edible Series, Reaktion Books) was released in April 2011. Her English translation of Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s tenth century CE Baghdadi cookbook, Kitab al-Tabeekh, entitled Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens (Brill, 2007), was awarded “Best Translation in the World” and “Best of the Best of the Past 12 Years” of the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards 2007. It also received Honorable Mention in 2007 Arab American National Museum Book Awards. She also co-authored Beginner’s Iraqi Arabic, with 2 audio CDs (Hippocrene, 2005).

All images featured in this interview have been cited, and any images from Ms. Nawal Nasrallah have been provided to Ancient History Encyclopedia solely for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction of text and images is strictly prohibited. Mr. James Blake Wiener was responsible for the editorial process. Special thanks is given to Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt for assistance in the editorial process. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE). All rights reserved. © AHE 2014. Please contact us for rights to republication.