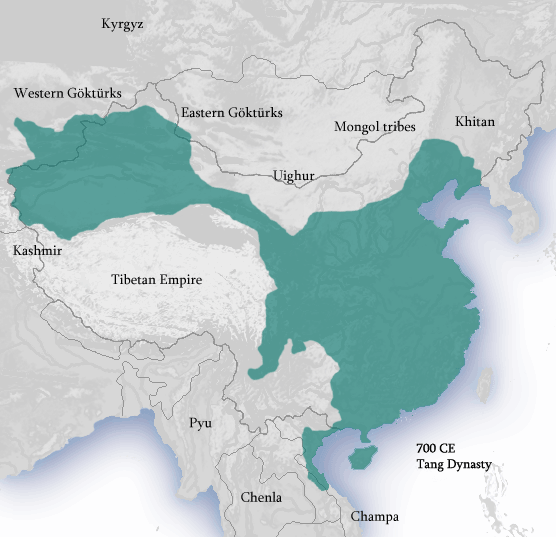

China’s Tang dynasty golden age is routinely described as one of the most brilliant eras in Chinese history. Under Tang rule and leadership, China became the wealthiest, most populous, and most sophisticated civilization on earth. While exerting political hegemony and a powerful cultural influence across East Asia, China was also open to influences from its Turkic and Indian neighbors.

In this exclusive holiday interview, James Blake Wiener of Ancient History Encyclopedia speaks to Dr. Jonathan Skaff, Professor of History at Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania and expert on Chinese-Turkic relations during the Tang era, who reevaluates Chinese culture and politics during an age of commercial trade, technological innovation, and ultimately, political instability.

JW: Dr. Skaff, what was it that first prompted you to study ancient and medieval China, and specifically Chinese-Turkic-Mongol relations during the Tang era?

JS: My fascination with the Chinese frontier can be traced back to my travels in China in the mid-1980s. After teaching English at universities in Shanghai for two years, I went on a long journey by train and bus to northwestern China. I stopped at a number of famous Silk Road cities, including Dunhuang, Turfan (or “Turpan”), and Kashgar. I became captivated with the ancient and medieval ruins and artwork, preserved due to the arid climate, and multicultural environment where Chinese were a minority among Turkic-speaking Uighurs and Kazakhs. When I returned to the U.S. and entered graduate school, I decided to focus on the medieval period because the Tang Dynasty was famed as a high point of cross-cultural contact along the Silk Road.

JW: The Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) marks a dramatic high point in Chinese civilization. I am curious to know which socio-political and cultural factors enabled China to attain a golden age of cosmopolitan prosperity after hundreds of years of turmoil following the collapse of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). Was it possible because Tang emperors favored civil Confucianism and established a new legal code — the “Tang Code” — that was based upon civil statutes and regulations?

JS: Well, James, I must warn you that I am not necessarily a conventional thinker when it comes to the Tang. My approach as a historian is to remain skeptical of longstanding stereotypes of the Tang — such as the idea that it was a “golden age” — until modern historians scrutinize these kinds of claims. As for socio-political factors, I think it is important to remember that the empire was only strongly unified from about 625-755 CE. During this time, internal unity and peace most likely contributed to domestic prosperity, but the wealth was mainly concentrated in the hands of the imperial family and elites in the dual capitals of Chang’an and Luoyang.

While life for the cosmopolitan elite of the capitals may have been grand, the vast majority of the population lived hardscrabble lives as peasant farmers. Though the military expansion of the Tang often is lauded, farming families suffered more hardships when their men were conscripted into the army. For example, in my research, I have examined surviving local census records from frontier regions in the early eighth century CE and found that the Chinese households only had a median of three people. One reason for the small household size was that almost half of adult women were widows. This is hardly a picture of prosperity in frontier provinces.

JW: The epoch of Tang rule in China coincides with a period of immense population growth due to the maturity of a money economy, the completion of the Grand Canal (joining the Yangzi and Yellow Rivers), advancements in mathematics and engineering, and widespread food surpluses throughout the countryside. Chang’an (Xi’an), the Tang capital, was the largest city in the world in Late Antiquity. Linked to the Silk Road, Chang’an was a multicultural metropolis with a diverse population of Chinese, Arabs, Persians, Khitans, Uighurs, Sogdians, and Tibetans.

Dr. Skaff, I am curious if the presence of foreigners contributed to religious tension in China, as the imperial court primarily patronized Confucians, Daoists, and Buddhists. Could you comment on the religious policy of the Tang emperors?

JS: For the most part, foreigners were welcomed and their religions were tolerated. The lone exception was in the mid-ninth century CE when Emperor Wuzong (r. 814-846 CE) suppressed Buddhism and other foreign religions. The motive of the emperor and his court seems to have been more economic than ideological. By this point, Buddhist monasteries had accumulated a great deal of land and wealth that were not being taxed. The seizure of Buddhist property temporarily solved a financial crisis. After the reign of Wuzong, the proscription on foreign religions was lifted. Buddhism continued to thrive because the populace never abandoned their beliefs. Some foreign religions with relatively small followings, such as Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity, never recovered.

JW: Some of the states paying tribute to Tang China included Nepal, Japan, Korea, Champa, and Kashmir. However, it was the Tang’s relationship with their Turkic neighbors that was of immense importance. Considerable cross-cultural exchange and interaction occurred, and it can be said that China would not have been as stable without the presence of Turkic mercenaries and generals within the ranks of the Chinese army. Why and how did this relationship develop?

JS: James, now you are touching on my field of expertise. The relationship between the Turks and North China extends back decades before the founding of the Tang to the time of the rise of the Turk Empire in the mid-sixth century CE. The first Turk ruler made a marriage alliance with the Western Wei dynasty (535-556 CE) of northwestern China to strengthen his hand against his nomadic rival based in Mongolia. With their flank secured, the Turks began conquests that resulted in the largest Inner Asian empire before the Mongol Empire of the 13th century CE. The Turks dominated North China at the time of the founding of the Tang dynasty in 618 CE during a period of civil war in China.

The first Tang emperor and his rivals in north China all sought peace with the Turks in order to strengthen their positions in domestic warfare. The Turks took advantage of the chaos to repeatedly raid North China. After the Tang consolidated domestic power, they attacked and defeated the Turks in 630 CE. For over 40 years, the Turks dwelled in North China as vassals of the Tang and fought in the armies that expanded the Tang Empire into Inner Asia. You can read more about the Tang-Turk relationship in my book, Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors.

JW: Many prominent figures from China’s past lived under Tang rule: Empress Wu Zetian (r.655-683 CE); Emperors Taizong (626-649 CE), Xuanzong the Elder (712-756 CE), and Xianzong (r. 805-820 CE); the famed poets, Li Bai (701-762 CE) and Du Fu (712-770 CE); and the notable painters, Han Gan (706-783 CE), Zhang Xuan (713-755 CE), and Zhou Fang (c. 730-800 CE). Of the historical figures from the Tang dynasty, which do you find the most intriguing and why? Do you have a favorite or one that you feel merits further study?

JS: To me, the most intriguing figure is Empress Wu. She is the only woman in Chinese history to found her own dynasty. Though a number of other empresses and dowager empresses excised power indirectly through weak husbands, sons, and grandsons, Empress Wu was extraordinary in using her political acumen and ruthless ambition to rise from a lowly palace concubine to emperor of China, usurping rule from the Tang from 690 to 705 CE. If readers are interested in reading a book about her, I recommend N. Harry Rothschild’s Wu Zhao: China’s Only Female Emperor.

My personal favorite as a subject of study is the second Tang emperor, Taizong, who played a prominent role in relations with the Turks. Like Empress Wu, he was ruthlessly ambitious. He came to power by assassinating his brother, the heir apparent, and usurping the throne from his father, Gaozu (r. 618-626 CE). Taizong subsequently proved to be a strong ruler who successfully balanced civil and military affairs to solidify Tang power over a multiethnic empire. It was under his rule that the Tang conquered the Turks.

JW: All golden ages come to an end, and after a series of forays into Central Asia, Chinese ambitions in Central Asia were checked by the Abbasid Caliphate at the Battle of Talas in 751 CE. This defeat precipitated the disastrous An Lushan Rebellion (755-763 CE), which interrupted Tang prosperity. As Tang power waned, resentment towards wealthy Arab and Persian merchants rose, resulting in the Yangzhou massacre (760 CE) and the Guangzhou massacre (878-879 CE). In 763 CE, the Tibetan Empire occupied Chang’an and expanded into Yunnan.

Dr. Skaff, aside from military defeat and rebellions, what led to the decline of the Tang dynasty in your opinion? What internal political weaknesses existed in the latter Tang era?

JS: That’s an excellent question that has not been fully answered. I plan to explore the topic of the An Lushan rebellion in a future book. The mid-Tang rulers were never able to fully reunify the realm as their forebears had done. One interesting theory put forth recently by historical climate scientists holds that the second half of the dynasty experienced lower levels of precipitation. If true, this would mean that agricultural output was lowered after 755 CE. Since agriculture provided most of the empire’s taxes, the late Tang court may not have had enough revenue to put armies in the field to defeat the autonomous provinces in the northeast. When I am researching my book, I will look for evidence to verify or refute this theory.

JW: Before concluding our interview, I wanted to ask you how should we interpret the legacy of the Tang dynasty in our modern era? Furthermore, why should we study Tang dynasty China, and what can we still learn about this important period in Chinese history?

JS: In general it is important for westerners to study ancient and medieval Chinese history because it still influences China’s present in various ways. First, Modern Chinese consider their past as sources of national and cultural identity. In the case of the Tang, your aforementioned reference to the Tang as a “golden age of cosmopolitan prosperity” contributes to feelings of national pride in China today. Many Tang poets, such as Li Bai, are still studied in schools today, reinforcing cultural links between past and present. Second, study of China’s past can help us to better understand deeply-embedded political and cultural patterns that persist in modern China. For example, my research demonstrates that personal connections were required for career advancement in government during the Tang, just as they are today. In terms of what we can still learn about the Tang, western scholars are behind those of China and Japan. For example, westerners have very few publications on periods such as the late Tang and topics such as economic history.

JW: Dr. Skaff, I thank you so much for your time and consideration. I hope that you will keep us posted as to your latest research.

JS: Thanks for taking time to learn more about the Tang dynasty. Good luck with your fantastic website!

Image Key:

- Map of the Tang Dynasty, c. 700 CE, at its apex. The Chinese controlled areas are shaded in green, while Turkic peoples and other polities are detailed as well. Original uploader was Hko2333 at en.wikipedia, 2008-27-08. (Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts.)

- A Tang sancai-glazed lobed dish with incised decorations, c. eighth century CE, at the Musée Guimet, Paris. Original uploader was Dsmdgold at en.wikipedia, 2008-24-01. (This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art.)

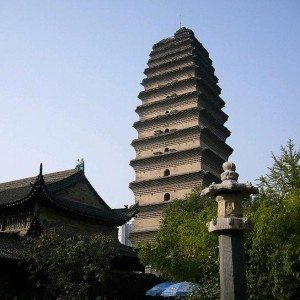

- Small Wild Goose Pagoda, built by 709 CE, was adjacent to the Dajianfu Temple in Chang’an, China, where Buddhist monks from India and elsewhere gathered to translate Sanskrit texts into classical Chinese. Original uploader was Guucancat at en.wikipedia, 2010-04-06. (This work has been released into the public domain by its author, Guucancat at the wikipedia project. This applies worldwide.)

- A famous Tang dynasty painting on paper of two prized horses and one rider by Han Gan (c. 706-783 CE). Original uploader was Colibrix at en.wikipedia, 2011-07-11. (This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art. This image (or other media file) is in the public domain because its copyright has expired.)

-

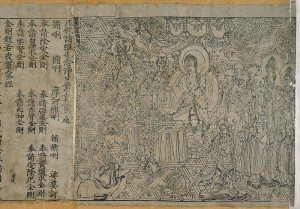

Frontispiece, Diamond Sutra from Cave 17, Dunhuang, China. Ink on paper. This page from the Diamond Sutra, printed in the ninth year of Xiantong of the Tang Dynasty, c. 868 CE. Currently located in the British Library, London.(British Library Or.8210/P.2) According to the British Library, it is “the earliest complete survival of a dated printed book.”

- Emperor Taizong (r. 626–649 CE) receives Ludongzan, ambassador of Tibet, at his court; painted on paper in 641 CE by Yan Liben (600–673 CE). Original uploader was Louis le Grand at en.wikipedia, 2006-30-08. (This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional, public domain work of art.)

Dr. Jonathan Skaff, is a Professor of History and Director of the International Studies Program at Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania. After teaching English at universities in Shanghai from 1984 to 1986, Skaff pursued graduate studies at The University of Michigan where he received his Ph.D. in History in 1998. His book, Sui-Tang China and its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power and Connections, 580-800 was published by Oxford University Press in 2012. In April 2016 he will deliver the annual M. I. Rostovtzeff Lectures at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University.

Dr. Jonathan Skaff, is a Professor of History and Director of the International Studies Program at Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania. After teaching English at universities in Shanghai from 1984 to 1986, Skaff pursued graduate studies at The University of Michigan where he received his Ph.D. in History in 1998. His book, Sui-Tang China and its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power and Connections, 580-800 was published by Oxford University Press in 2012. In April 2016 he will deliver the annual M. I. Rostovtzeff Lectures at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York University.

All images featured in this interview have been cited. Unauthorized reproduction of text and images is strictly prohibited. Special thanks is extended to Ms. Karen Barrett-Wilt for assistance in editing this interview. The idea for this interview came via Mr. Mark Cartwright with aid from Professor Valerie Hansen of Yale University. Mr. James Blake Wiener was responsible for the editorial and publication process. The views presented here are not necessarily those of the Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE). All rights reserved. © AHE 2014. Please contact us for rights to republication.