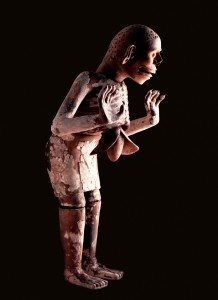

Wings outspread, jagged talons projecting front and back from his knees, his face emerging from an eagle’s beak, this is an eagle warrior. Templo Mayor Museum, INAH. National Council for Culture and Arts – INAH.

Around 1325 CE, southward migrating Mexicas or “Aztecs” came upon an island in Lake Texcoco, located in the highlands of Central Mexico. On this spot, they consecrated a temple and founded their capital city — the legendary Tenochtitlán — from which they initiated a wave of imperial conquests throughout Mesoamerica. Aztec civilization flourished for nearly two hundred years before falling to the might of the Spanish, led by Hernán Cortés (1485-1547 CE), in 1521 CE. Despite their remarkable innovations in engineering, agriculture, and architecture, many remember the Aztecs solely for their bloody rituals of human sacrifice.

This summer, Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology and History Museum in Montréal, Canada presents a major international exhibition, The Aztecs, People of the Sun, which offers glimpses into the lost world of a culture that reigned over much of what is present-day Mexico. In this interview, James Blake of Ancient History Encyclopedia (AHE) speaks to Ms. Christine Dufresne, Project Manager at Pointe-à-Callière, about the exhibition and the finer points of Aztec civilization.

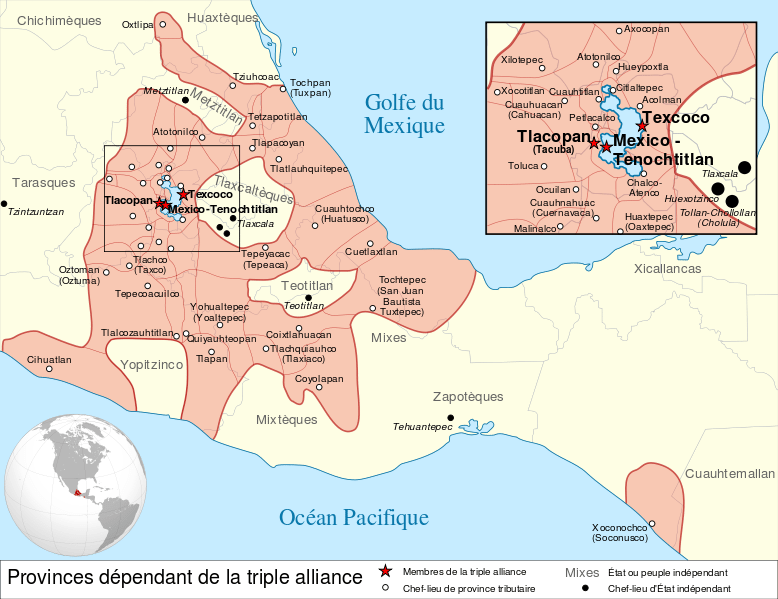

A map indicating the maximum extent of the Aztec civilization which flourished between c. 1345 and 1521 CE in what is now Mexico. The three major cities which formed the Aztec Triple Alliance were Tenochtitlán, Texcoco and Tlacopan.

JW: Welcome to Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ms. Christine Dufresne! Thanks for speaking with me about The Aztecs, People of the Sun, which is currently on show at Pointe-à-Callière in Montréal, Canada.

I’m curious to know if you had any misconceptions about Aztec civilization or art before organizing this exhibition?

CD: The most surprising thing for me was learning about the splendid city of Tenochtitlán. In addition to being constructed on pilotis, the Aztec capital was one of the world’s greatest cities when the Spanish arrived in 1519 CE. Whereas Seville — Spain’s largest city at the time — had a population of close to 30,000, Tenochtitlán was home to nearly 200,000 people (300,000 if the surrounding population is included). In addition to its size, the city was a shining example of the Aztecs’ technological and architectural advancement. The heart of Tenochtitlán was a walled space with four openings onto the four main causeways through the city. There were some eighty buildings there. The Spanish were amazed at the splendors of the city, comparing it to Venice, Italy.

The history of the Aztecs is truly fascinating. Even though the Spanish conquered them and destroyed their capital, many traces of their civilization still remain. In fact, the Mexican flag depicts the founding myth of the capital city — an eagle perched on a cactus, devouring a serpent.

JW: It’s widely known that the Aztecs practiced human sacrifice in their temples, but many do not understand its immense importance within the Aztecs’ worldview. What knowledge can you share with us about this topic? Which artifacts in the exhibition are related to this custom?

His skull-like features, small holes where hair would be attached, flayed skin stained with human blood and claw-like hands make Xipe Totec a terrifying god of the dead! Templo Mayor Museum, INAH. National Council for Culture and Arts – INAH.

CD: We are, in fact, featuring several objects related to human sacrifices, including statues representing Aztec gods, knives, offerings, and vases used in rituals. It is important to understand the Aztecs’ concept of the world in order to understand the role and function of the sacrifices. According to the myth of the fifth sun, the gods gathered at the ancient city of Teotihuacan to create the sun, which was indispensable for the survival of humanity. They agreed that one of them had to be sacrificed by throwing himself into a sacred fire. Two gods volunteered: Nanahuatzin, who reappeared as the sun, and Tecuciztecatl, who became the moon. However, this was not enough to start the new world. The sun declared that it would not embark on its course unless all the other gods also offered their blood. So they all agreed to perish together in the divine flames.

The Aztecs regarded innumerable human sacrifices, which so horrified their indigenous rivals (the Tarascans, Huatecs, Mixtecs, and Zapotecs) and the Spanish, as an imperative religious rite. Just as the gods had sacrificed themselves for humanity, people had to die so that the sun would emerge from the underworld every morning and resume its course. This is why they captured prisoners in what they called the “Flower War,” and executed them in a magnificent ceremony soon afterwards. In fact, this kind of death was envied by all Aztecs, since it earned the victim the greatest possible honor — that of entering the army of the sun and accompanying it across the sky.

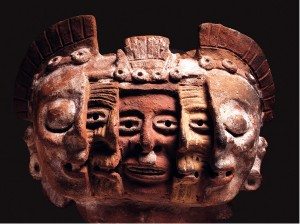

This Aztec ceramic fragment with three faces shows the three phases of existence. In the center is youth, opening his eyes to the world. Next is old age. Finally comes death with closed eyes. University Museum of science and arts, UNAM. National Council for Culture and Arts – INAH.

JW: One of the highlights of the exhibition is a splendid ceramic piece with three faces, adorned with 13 circular gems, or chalchihuitl, evoking the 13 months of the sacred calendar. It decorated a brazier or a funerary urn, and depicts the three phases of existence according to the Aztecs.

How do Aztec calendars play a key role in our understanding of Aztec views of life and death?

CD: For the Aztecs, time was cyclical. At regular intervals, each in turn, different gods influenced human existence, based on two interlocking calendars. The solar calendar (xiuhpohualli), or annual calendar, had 365 days. It consisted of 18 months of 20 days each, making up 360 days (18 x 20). The remaining 5 days were considered extremely unlucky, a time during which it was best to avoid any activity! The calendar was adjusted every four years, as we do with leap years nowadays. Each month was dedicated to a major god, whom people would honor at that time. And since this calendar dictated the agricultural year, many festivals were dedicated to Tlaloc, the god of rain, or to other agricultural deities, like Xochipilli and Coatlicue.

The sacred or divinatory calendar (tonalpohualli) also determined the dates of religious ceremonies and other important events. Each of its 20 days was defined by a glyph and a number from 1-13. These signs and numbers combined in an unchanging order with different permutations of a sign and number, yielded 260 different possibilities. Every 52 years, the solar and sacred calendars aligned, and this was a very fearful time for the Aztecs.

Tenochtitlán, a city founded by the Aztecs, was called the “Venice of the New World” by the Spanish conquistadores. Caroline Bergeron, Pointe-à-Callière.

JW: In what ways were the Aztecs great innovators? Do any of the items in The Aztecs, People of the Sun attest to their prowess in engineering or agriculture?

CD: It should be noted that Tenochtitlán was a spectacular city overflowing with luxurious palaces, magnificent temples, and sprawling markets. Built at an altitude of over 2,000 m (6,562 ft), the Aztec capital was divided into four quadrants, each protected by gods associated with the four cardinal directions. In this “Venice of America,” people moved around by canoe as much as on foot. Everywhere there were canals leading to homes and lavish gardens. Drawbridges connected this island city to the mainland or cut it off, when necessary. A dike with sluice gates made it possible to control the level of the lake and prevent flooding. An aqueduct brought pure spring water from the mountains since the shallow, brackish lake water was undrinkable.

The Aztecs managed to maximize the space available for dwellings and agriculture on their small swampy island; they planted pilings in the shallow water, erected retaining walls, and filled them with mud dredged from the lake. Thanks in part to these floating gardens (chinampas), Tenochtitlán and the area around it were lined with canals. The gardens were remarkably fertile, producing up to seven crops a year and feeding much of the city. The Aztecs even fertilized the city’s crops with organic waste if you can believe it. Several objects in the exhibition demonstrate how important agriculture — especially corn (maize) — was to the Aztecs.

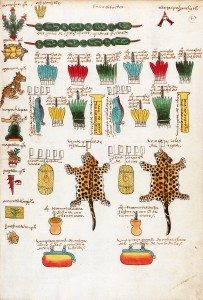

What we know about the Aztecs comes from a multitude of archaeological discoveries, but also from historic sources, including the precious codices that the Aztecs wrote themselves. This page shows the tribute to be paid every six months by the eight cities. Gianni Dagli Orti/The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY.

National Council for Culture and Arts – INAH.

JW: Despite the defeat of the Aztecs at the hands of the Spanish, we can say with complete affirmation that many of the vestiges of Aztec civilization remain. Mexico City, one of the world’s largest cities, is built directly upon the ruins of Tenochtitlán, and there are over one million speakers of the Aztec language, Nahuatl, today.

In your own words, how would you characterize the legacy of the Aztecs? Moreover, why do you believe we ought to study their history and culture?

CD: The history of the Aztecs is truly fascinating and worth learning about. Even though the Spanish conquered them and destroyed their capital, many traces of their civilization still remain. In fact, the Mexican flag depicts the founding myth of the capital city — an eagle perched on a cactus, devouring a serpent.

Even today, we are captivated by the civilization’s magnificence and the material remains it left behind. The remains of Templo Mayor are a magnificent architectural example of this civilization. Unlike Egyptian pyramids, Aztec temples were shaped like mountains. The Templo Mayor, the greatest of them all, stood in the heart of Tenochtitlán. When Cortés arrived, this temple was approximately 45 m (148 ft) tall and 86 m (282 ft) wide. The Templo Mayor was the center of the world and the main site for sacrifices to the gods Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. Today, the site is one of only two archaeological sites in North America that preserve the birthplace of a city — the other being Pointe-à-Callière, which houses the remains of Fort Ville-Marie, the settlement that grew to become present-day Montréal, Canada.

JW: I thank you so much for speaking with me, and I congratulate you on having produced a fantastic exhibition!

CD: Merci James!

The Aztecs, People of the Sun will be on show at Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology and History Museum until October 25, 2015. A handsome exhibition catalogue of 102 pages supplements the exhibition.

Ms. Christine Dufresne holds a Bachelor’s degree in Art History from Université Laval and a Master’s degree in Museology from Université de Montréal/UQAM. Since 2005, she has been the Project Manager at Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal’s Archaeology and History Complex. Ms. Dufresne’s duties include planning, producing, monitoring, and ensuring the renewal of temporary and permanent exhibitions presented at Pointe-à-Callière. She has worked on such large-scale exhibitions as The Aztecs, People of the Sun (2015), The Greeks — Agamemnon to Alexander the Great (2014), and The Etruscans — An Ancient Italian Civilization (2012). She has also been involved in a number of projects relating to outreach, education, and cultural activities, as well as special events. Ms. Dufresne is also responsible for representing the Museum among other organizations and partners. On occasion, she also gives talks and can be heard in interviews with the media. Prior to 2005, Christine Dufresne worked as an exhibition project manager at the Museum of Fine Arts, and as General Director of the exhibition center at Salle Augustin-Chénier, a center affiliated with the Department of Culture and Communications.

All images featured in this interview have been attributed to their respective owners. Images lent to the Ancient History Encyclopedia by the Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archeology and History Complex have been done so as a courtesy for the purposes of this interview. Unauthorized reproduction is strictly prohibited. A heartfelt thank you is extended to Ms. Pascale Dudemaine, Communications Advisor at Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology and History Complex, for her assistance in facilitating this interview. All rights reserved. © AHE 2015. Please contact us for rights to republication.