During my last visit to London, I resided in a hotel at Gower Street of Bloomsbury. By chance, I discovered a hidden gem within the heart of University College London while surfing Google. It was located just few minutes away from me: the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. The Museum lies at Malet Place, hidden away from the main streets.

The Museum’s building and façade do not convey any message to the public that this is one of the most important museums in the world, housing more than 80,000 ancient Egyptian objects and artifacts! Actually, it ranks fourth, after the Cairo Museum, the British Museum, and the Egyptian Museum of Berlin in terms of the number of quality of ancient Egyptian objects. I emailed the Museum, requesting permission to take no-flash photos of the objects. Ms. Maria Ragan, the manager of the Museum, kindly replied and granted me permission. OK, let’s go!

The facade of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, University College London, Malet Place

London. The entrance door is just behind the walking women (with the blue dress). It will take you to the upper floor where the Museum’s rooms (halls) are located. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Once you ascend to the upper floor, you will face the information desk. The staff are very friendly, cooperative, and helpful. The information desk employee will give you information about the galleries of the Museum and how to proceed.

One of the galleries of the Petrie Museum. At the right, there is a stair which descends you to another room/gallery. The displaying case at the right contains the so-called mummy portraits from Hawara. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

One of the galleries at the Petrie Museum. There is a table where you can sit, read, give a lecture…etc. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

I really enjoyed the friendly environment of this “small” museum.

In the year 1892, the Department of Egyptian Archaeology and Philosophy was established at the University College London (UCL). Meanwhile, the museum was established as a teaching resource for that Department. The writer Amelia Edwards (1831-1892) left her legacy by donating a large number of Egyptian artifacts to the museum. Gradually, the museum’s content expanded enormously, thanks to the great work and effort of Professor William Flinders Petrie (1853-1942). Petrie excavated several important ancient Egyptian sites, such as Hawara, Amarna, and Meydum. In 1913, Petrie sold his personal collection of Egyptian artifacts to UCL. This had greatly expanded the museum’s content and made it one of the largest collection of Egyptian objects outside Egypt at that time. Gradually, the museum’s collections were arranged in galleries; however, it was not open to the public. Only students and academics were able to access the collections.

During World War II, the museum was evacuated and its contents were transferred to a safe place outside London. During the 1950s, the museum’s objects were transferred back and kept temporarily in a former stable building, where it remains today. The museum is open to the public from Tuesday to Saturday, 1 to 5 PM. Entrance is free.

Cartonnage mummy masks. Wealthier ancient Egyptians were keen to prepare for the afterlife. A mummy case was important part for the funerary equipment. After the body was embalmed and wrapped, in a linen bandage, the mummy was placed in case of coffin. Egyptians of a high social status often had lavish and colorful cases. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The upper part of a double statuette of a husband and wife. Both might have been depicted seated. There are 7 vertical columns of hieroglyphic inscriptions carved on back (with funerary prayers for the owners). Their names were not preserved. From Egypt, precise provenance of excavation is unknown. 18th Dynasty, 1352-1292 BCE. From the Amelia Edwards Collection. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Detail of a mummy portrait from Hawara; these portraits are one of the top 10 masterpieces of the Museum. This is a thin lime (Tilia species) wooden panel with encaustic wax mummy portrait. of Petrie’s “red youth”. The man has curly light beard and moustache. It appears that a sharp tool was used to delineate the shape of the face, ears, and eyebrows. From Hawara cemetery, Egypt. 1st to 2nd centuries CE. With thanks to The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. The Petrie Museum has the largest collection of these “portraits” outside of Egypt. Originally, these portraits were placed over their mummified body; these images were hailed as the 1st life-like representations of real people on their 1st exhibition in London in 1888 CE. These portraits were excavated in 1888-1889 CE and 1901-1911 CE. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Papyrus will of Antef Meri, leaving offices and property (recto) and endorsement (verso). Hieratic in black ink. The papyrus is still in a good condition but frayed at the edges. From Lahum, Fayum Governorate, Egypt. 12th Dynasty, year 39 of Amenemhat III. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- God Osiris statuette; white metal with a golden overlay.There is a ring at the back of neck for suspension. The feet were broken off and missing. He wears the upper Egypt crown with ostrich feathers and holds a flail in the right hand and a long crook in the left hand. From Egypt. 26th Dynasty, 664-525 BCE. Note that the description was written using a typewriter! With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Limestone head of a man. Petrie thought that this is king Narmer of the 1st Dynasty. Petrie bought it from Egypt, precise provenance of excavation is unknown. 1st Dynasty, 31st or 32nd century BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Winged phallus terracotta mould. The wings extend from the sides of the shaft, above the testes. There is a hole at the mid-shaft for suspension. From Memphis, Egypt. Gaeco-Roman Period, 30-390 CE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- The conservation and assemblage of this necklace which was found at Amarna, Egypt, was made possibly with the generous sponsorship of Mrs. Pamela Littman. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin

“Shabtis” from the tomb of Horwedja, a priest of the goddess Neith. From Hawara, Egypt. Late Period, 30th Dynasty, circa 380-343 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The bead net dress, one of the top 10 masterpieces of the Museum. From Qau, Egypt. 5th Dynasty, 2498–2345 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- This is one of the 10 top masterpieces of the Museum. It is a fragment of a relief (probably part of a balustrade) with a deep sunk relief. Pharaoh Akhenaten (headless) is followed by his wife Nefertiti and Meritaten. He stands before an offering table with 3 jars, to which the hands of the Aten are extended. Early cartouches of Aten on arms and chest of king can be seen. Column of hieroglyphic inscriptions are carved in front of Nefertiti. They read “Nefer-neferu-aten Nefertiti, may she live forever and ever”. In addition the hieroglyphs above the princess read” Merit(aten), born of the Great Royal Wife, Nefer-neferu-aten, Nefertiti, may she live forever and ever”. From Amrna, Egypt. 18th Dynasty, 1353–1336 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- This is one of the top 10 masterpieces of the Museum. This is a painted cream-ware pottery bowl. It was reconstructed from fragments and has a rounded base, The interior was painted with brown vine stems and leaves. The exterior surface was painted with leaf motifs between parallel sets of lines. From cemetery 300 at Meroe, Sudan. Meroitic period, 300 BCE to 400 CE. With thanks to The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- This is one of the top 10 masterpieces of the Museum. This is a pot burial from Hememieh (near the village of Badari). The skeleton belongs to a male adult, over 6 foot in height. Old Kingdom, 2686-2181 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- This is one of the top 10 masterpieces of the Museum. This limestone block fragment came from the debris of the north wall of the antechamber within the pyramid of king Pepi (Pepy) I at Saqqara. The fragment contains 5 vertical columns of green-filled hieroglyphic inscriptions. The cartouche of the king Pepi was carved four times. The inscriptions describe the formulae for the ascent of the king to heaven and for his eternal supply of food and drink. From Saqqara, Egypt. Old Kingdom, 6th Dynasty, 2332-2287 BCE. With thanks to The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

This is a protective amulet called “cippus or Horus stela”. It depicts the god Horus as a naked child, standing on 2 crocodiles with oryx and serpents in each hand. God Bes can be seen at the upper part. The cippus is inscribed in hieroglyphs on all faces with words to be spoken in defense of health (mainly against snake and scorpion bites). From Egypt. Ptolemaic Period, 305-30 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- A pair of fine palm-fiber sandals. From Sedment, Egypt. 18th Dynasty, 1543–1292 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Flint hand axe, chipped. From Fayum, Egypt. Neolithic Period. With thansk to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Bronze arched “sistrum”. A bust of Horus the Child can be seen on the top of arch in a Roman style. From Egypt. Roman Period, 30-390 CE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

As I shot more than 10,000 photos over two days, I had difficulty choosing what pictures to post on this article. It is impossible to cover all of the wonderful objects of this museum within this article. However, I have posted a large number of the museum’s images on the Ancient History Encyclopedia website, as illustrations; for instance, you will find all of the collection of Hawara mummy portraits there. I really enjoyed the friendly environment of this “small” museum. If you are in London or are visiting London, don’t forget to visit the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology! It is just 10-15 minutes walking from the British Museum. You may also read “The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, Characters and Collection” by Alice Stevenson; you can also download the book’s PDF for free from that link!

Quartzite block statue of an Egyptian official with a naos (shrine) in front of him, containing the god Ptah. Cartouches of Pharaoh Ramesses II are inscribed on upper arms of the official. Formerly in the Wellcome Collection (Gift of the Wellcome Trustees). From Egypt. 19th Dynasty, 1292–1189 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

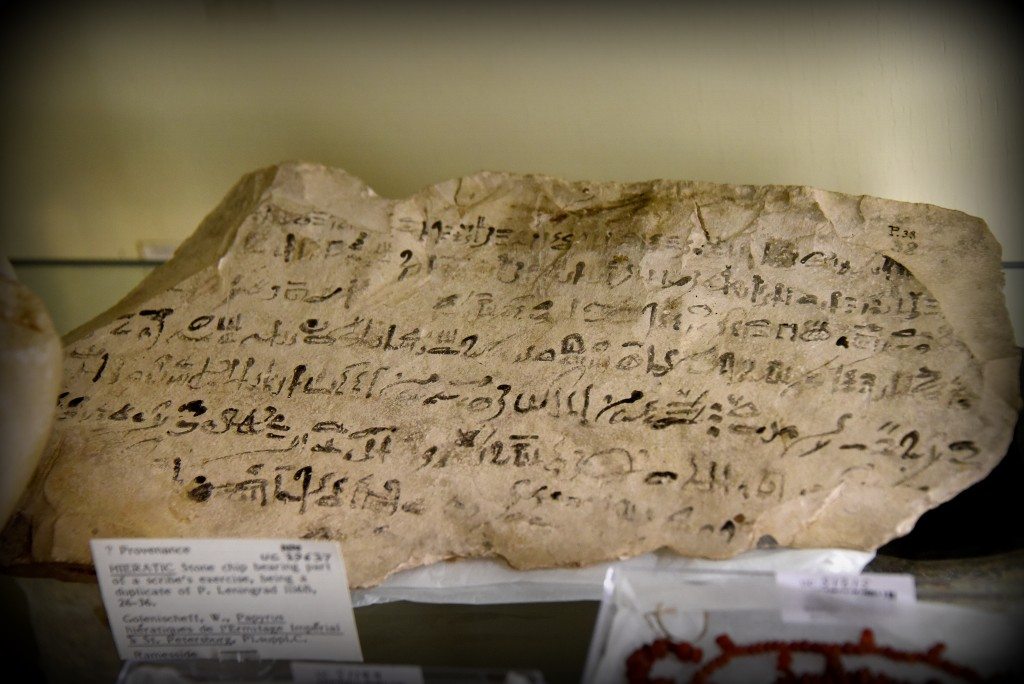

This is a limestone ostracon which bears on one side parts of 8 lines of hieratic inscriptions (in black), giving part of the “Prophecy of Neferty”. At the center top, one area seems to have flaked off and then been re-attached in more recent times. At bottom right a sign has been written over the edge; the reed slipping onto the underside. From Egypt. Ramesside period, 1292–1069 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Limestone offering table with a rectangualt basin. There are hieroglyphic inscriptions (offering formula) on the rim. From Saqqara, Egypt. Old Kingdom, 5th Dynasty, 2498–2345 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Hippopotamus ivory comb. From tomb 25/5130. El-Badari, Egypt. Badarian Period, circa 5000-4000 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- This is one of the do-called b”lack-topped red” vase. From the Hierakonpolis Main Deposit, Egypt. Early Dynastic Period, circa 3100 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

- Foundation stone from the mortuary temple of queen Tausert (Tawesret). Double cartouches of the queen was carved on this plaque. From Thebes, Egypt. 19th Dynasty, 1292–1189 BCE. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

And last but not least, the Tarkhan dress; this is one of the top 10 masterpieces of the museum. I tried to shoot it from different anglers, but I failed to get rid of these light reflections! But, I have to include this object here, as it is one of the oldest garments from Egypt on display in the world. The dress might belong to a young teenage or a slim woman. Petrie found it inside Mastaba 2050 at Tarkhan, Egypt in 1913 and dated it back to the 1st Dynasty, circa 2800 BCE. The dress was put in the tomb in an inside-out way. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Visiting the Petrie Museum

Free admission

Opening hours

Tuesday to Saturday 13:00 – 17:00

Address

The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology

University College London

Malet Place

London

WC1E 6BT

Contact

+44 (0)20 7679 2884

petrie.museum (AT) ucl.ac.uk

Acknowledgments

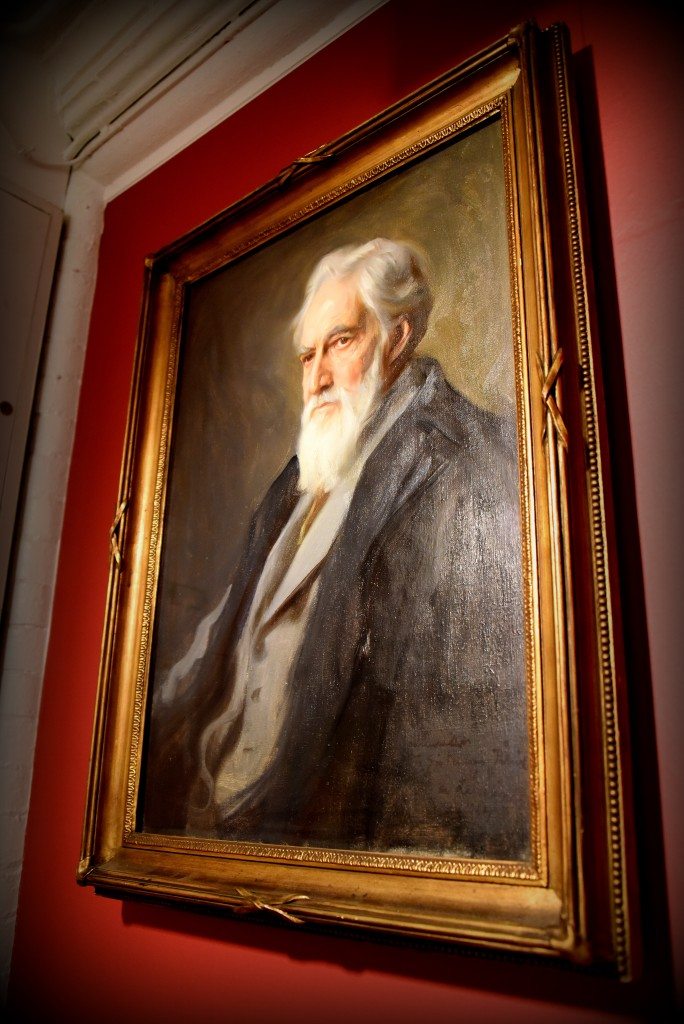

Portrait of late Professor William Mathew Flinders Petrie (RIP) by Philip Alexius de Laszlo (1934). This less formal depiction of Petrie was painted by de Laszlo for Petrie’s family. It was lent to UCL by Hilda Petrie to be put on display with the Petrie Collection at the time of the celebration around the centenary of Petrie’s birth in 1953. The portrait is now housed in the Petrie Museum. With thanks to the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, UCL. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

I sincerely thank all the staff and management of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology; without their kind help and cooperation, this article would have not been published. A special gratitude goes to the late Professor Petrie. Without his enormous work and effort, the world would not have enjoyed seeing these ancient Egyptian artifacts.